In Rashi’s Chamber

| August 17, 2021To mark Rashi’s yahrtzeit, Yaakov Amsalem visited the ancient French city of Troyes, where the greatest Jewish commentator of all time lived

Photos: Yaakov Amsalem

Tangible Elements

A wooden chair with a tall back, a simple table for a shtender, and a lantern light fixture that has seen better days. These ancient items greet us upon our entering the restored study of the mefaresh hadas, the one whom Ibn Ezra calls Parshandasa, Rabbeinu Shlomo Yitzchaki zy”a.

Rashi. The name sends a tremor through the heart of everyone learning Chumash, Navi, Kesuvim, or Shas. It is virtually impossible to learn without Rashi’s help. His greatness in Torah, his refined middos, and his tremendous humility are plainly evident to anyone reading his holy words.

Rashi’s study, located in the heart of Troyes, France, a three-hour drive southeast from Paris, was restored by the local Jewish community, known as Kehillas Rashi. For most of his life, Rashi lived in Troyes, serving as the rav of its small Jewish community in addition to writing his Torah commentary and halachic teshuvos to questions sent to him from all over the world. The narrow lanes of this sleepy little town played host to Rashi’s daily walk from his home to this study room.

When I arrived in Troyes on a Friday a few weeks ago, Rashi’s room was still locked due to Covid restrictions, but it was opened in honor of my visit.

Rashi is so well known, yet so unknown; no image exists of the sage, and to this day, no one knows the precise location of his grave (although we visited the “Jewish field” in Troyes, where, according to tradition, Rashi is buried). Anyone who learns his commentary recognizes his style, which offers a simple explanation of the pasuk, yet somehow manages to smooth out every difficulty. In every generation, Jews touch Rashi through his commentary. But here, in this restored study room, one can perhaps imagine some of the tangible elements that were part of his daily routine.

The Fire and the Restoration

Not much has changed here in 1,500 years. Surrounded by villages and pastoral fields, the city of Troyes today (population 62,000) is the capital of the departement of Aube in the Grand Est region of France; before the Revolution, it was the seat of the province of Champagne.

The Jewish presence in the city is centuries old. Documentation from Rashi’s time shows a small community of some 100 people, most of whom cultivated vineyards to produce wine. Local Jews endured endless persecution, most notoriously the blood libel of 1288, which led to the deaths of about a tenth of the community. The remainder left when King Philip V of France expelled the Jews from his realm a few years later.

Only almost six centuries later, in 1877, did the Jews return to Troyes, establishing a small shul. That community has since survived World War II, but has never grown beyond a few hundred members. Today there is one active shul, in the complex where Rashi’s study has been restored.

“My father understood that we needed to do something to revive the Jewish community here,” says Joël Samoun, president of the Troyes Jewish community and son of the community’s previous rav, Rabbi Abba Samoun z”l.

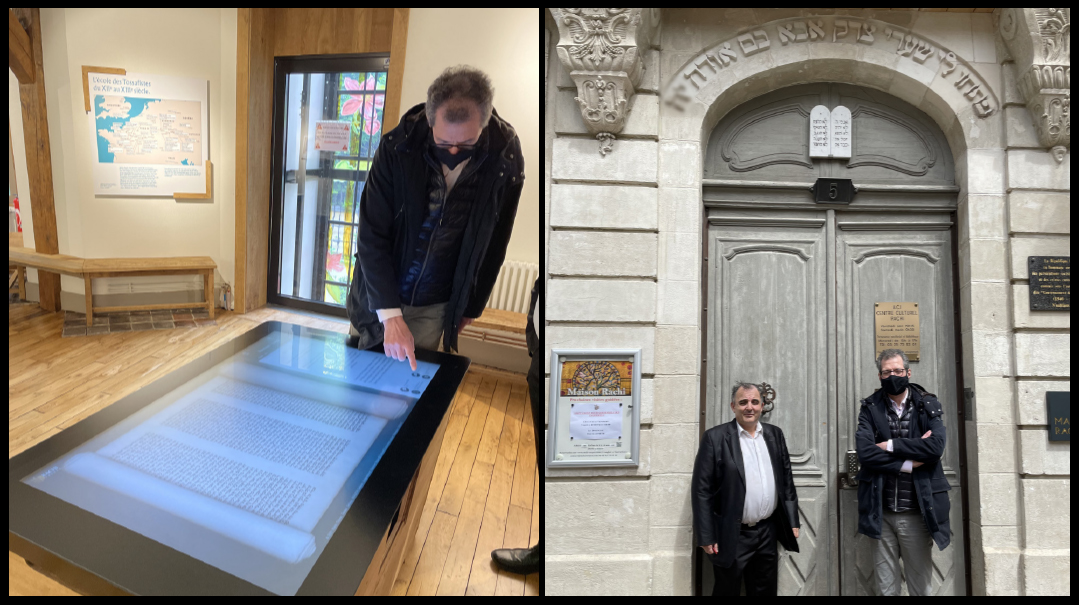

Joël Samoun directs the local community center, three two-story buildings that house the Rashi Museum: the restored study room, a library of all the seforim that contain Rashi’s commentary, a presentation room that makes the history accessible to visitors, and a computer room that projects a large sefer Torah on a screen; users can click on any pasuk and see Rashi’s commentary on the selection. Samoun hopes to recreate a world that was largely lost to a devastating fire.

“Five hundred years ago, many homes in Troyes were burned down,” he says. “Among them was Rashi’s beis medrash. Over the years, other houses were built over it and Rashi’s legacy faded. As a basis for the study room restoration, we delved into historical sources and written testimonies that described it — the room that sent forth his commentary to the whole world.”

Filling a Niche

Something about the unique charm in Troyes’ ancient streets is no doubt influenced by the city’s most famous son. The streets are paved not with asphalt but rather with small square cobblestones. The homes are two stories, constructed of wide wooden beams with stucco tiles in between.

Rashi and his grandchildren, Rabbeinu Tam and Rashbam, walked these streets. Thinking of what they must have discussed each day on their return from the beis medrash fires the imagination.

Visitors seeking the legendary indentation in the wall, however, will be disappointed. Supposedly before Rashi was born, his mother was walking in a narrow lane when a Christian cavalryman galloped in from the other end, threatening to trample her. She pressed herself against the wall, and a niche miraculously formed, saving her.

Many researchers, including Reb Raphael Halperin z”l, who wrote a book about the life of Rashi, say that if this occurred at all, it happened in Worms. Samoun and others in Troyes cast doubt on this, insisting that Rashi’s mother never lived in Worms, and was born and died in Troyes.

But a tour of Troyes ancient streets fills another niche: One can come to a new appreciation of Rashi’s commentary on such subjects as eiruv chatzeiros using the measurements of the courtyards and the roofs.

“We can assume with certainty that Rashi meant in his commentaries the streets of Troyes,” Samoun says. “That’s what he saw in front of his eyes and that is how he derived his conclusions for his commentary on the Talmud.”

A Painful Mystery

Rashi’s burial site is a painful mystery. After his passing on 29 Tammuz 4865/1105, Rashi was buried in the old Jewish cemetery, called “Jews’ Field.” But sadly, all trace of the graveyard was erased centuries ago.

“About five or six hundred years ago, the gentiles destroyed the cemetery in order to expand the city,” Samoun says somberly. “More recently, they built a theater and arts center, with a large paved parking lot alongside it.”

A large monument in the shape of a silver ball, created by French artist Raymond Moretti, was unveiled in 1990 in front of the building, bearing a Hebrew inscription in Rashi script. A few years ago, the Ohalei Tzaddikim organization, headed by Rabbi Yisrael Meir Gabbai, estimated that the location of Rashi’s original gravesite was near this memorial ball, but there is no proof. The assumed burial site draws no pilgrimages.

France is Very Proud

We are joined by Philippe Bokobza, a member of the Jewish community who operates the recently opened museum.

Samoun and Bokobza show me around the shul, still closed due to local Covid restrictions. It hosts some 5,000 tourists a year, but surprisingly, Samoun says, about 70 percent are non-Jews interested in Rashi. “On a daily basis we get tourists here from all over the world who have somehow become aware of Rashi’s story and his writings, and they want to see the place where he worked and learn more about him.

“Government schools here consider him a French historical figure, not only a Jewish one. France is very proud of the fact that Rashi lived there.”

Anyone passing by the shul cannot help but notice the pasuk “Pischu li shaarei tzedek avo vam odeh Kah” carved over the wide entrance. Above the aron kodesh is another engraving, this one the pasuk from Parshas Balak, “Mah tovu ohalecha Yaakov mishkenosecha Yisrael.”

My two hosts explain that this pasuk is the motto of the shul and the community. The construction of the museum was completed exactly six years ago during parshas Balak. Bokobza directs my attention to the transparent glass ceiling in the main sanctuary, which looks up into a tent that is part of the construction on the second story.

“This is the ‘ohalecha Yaakov,’ ” he says. “We built it in memory of the pasuk that is found throughout this complex numerous times.”

The restored replica of Rashi’s study room is on the top floor. The furnishings are made from ancient walnut wood, and the room’s design was based on various period illustrations. Half of the room is built like a small shtibel, with old benches and a small aron kodesh, without a paroches. Natural light and kerosene lamps are the only forms of illumination.

“Coming in here gives a feel for the atmosphere Rashi lived in more than 900 years ago,” Bokobza says.

In the next room is a community auditorium. One wall features a stained-glass presentation of Rashi’s genealogy tree, documenting his descendants as long as 200 years after his passing, when the Jews were banished from Troyes.

“We used these materials because Troyes has always been a global center for colored glass techniques,” says Bokobza. “So this brings it full circle, in a way.”

A separate hall houses the library containing the seforim with Rashi’s commentary or mentions of him. The collection includes about 300 volumes written about Rashi in various languages.

The library also features a video wall that screens productions created by the community, depicting the restoration of the local market, the living experience in Troyes during the time of Rashi, and explanatory segments about Rashi’s legacy and the change he effected in the Torah world with his commentary.

“For us, these are known things,” Bokobza says, “but non-Jewish visitors who come display remarkable interest, and these resources provide them with a most expansive illustration of Rashi’s legacy.”

“People of the Book” Effect

As the years passed, the younger people began to leave, and again, the already-small community began to shrink.

“Like in every remote city, the young ones left Troyes in favor of education options in Paris or Israel,” says Michel Amar, a younger member of the community. “At the same time, the elderly were passing on. We needed something to connect the members of the community and give added value to its activities. That was when the idea was born to develop the legacy of Rashi.”

So when the Troyes shul began to show signs of structural fatigue, about 15 years ago, community president Rona Fitton decided to start renovations, which included plans for the museum. Those renovations were complete six years ago. The community’s hopes seem to have borne fruit; when Covid restrictions were not in effect, the Rashi museum is very busy and generates a lot of national interest.

“I think the most interesting thing here is the way the museum contributes to reducing anti-Semitism, through Rashi’s memory,” says Philippe Bokobza. “We discovered that when we speak about Jews in a historical context, it generates empathy from the listener and gives him a connection to the Jewish nation, and makes him reconsider what he previously thought.”

This phenomenon is called the “People of the Book effect,” Bokobza says, and has been observed in other circumstances as well.

“Over the years, anti-Semitism has been based on various and sundry accusations about the Jewish nation,” he says. “In the past it was the notorious blood libels, and Jews are vilified for their greed and financial power. At least in France, this is the primary accusation that fuels those who hate Jews. When we emphasize a joint historical view of Jews and French — which is Rashi, who lived in France — this increases identity and solidarity with the Jewish nation.”

A prominent example of this came a few years ago when French president Emmanuel Macron spoke to French immigrants living in Israel. Macron chose to mention the memory of Rashi, a French resident, as someone who influenced the entire Jewish nation.

“He recognizes the importance of Rashi’s memory, as do many other French people, who are becoming more and more enlightened about him,” says Bokobza.

Antidote to Anti-Semitism

Seeing the power of Rashi’s memory in reducing animosity toward Jews, community officials created a program of student tours for non-Jewish schools in Troyes.

“Each week, a few dozen students come here,” says Joël Samoun. “They tour the shul, visit the study room, view the historical materials, and emerge from their visit thinking more positively about the Jewish People. We’ve made it possible to tangibly feel the history of the Jewish nation in this place, emphasizing the persecution that we’ve endured over the centuries.”

These tours led to national French schools forming workshops about Rashi’s legacy. “In one French school, they held a workshop in which they learned about Rashi and the uniqueness of his writing. At the end of the workshop, every student is asked to write his name in Rashi script. This whole process makes it so accessible for everyone, and produces amazing results.”

The workshops also provide explanation about such concepts as a shul, a sefer Torah, and an aron kodesh.

“They begin to understand that Jews are not like what they hear about in the media, and sometimes even at home, because some of their parents do not like Jews, to put it mildly,” says Samoun. “When you bring a young child to such a place, his view of the Jewish nation changes, and he simply grows up differently.”

Samoun says he once asked one of the tour guides — who is not Jewish — what connects him to Rashi.

“He gave a remarkable reply: ‘As a Frenchman I feel it to be a merit that such a great figure grew up here in my homeland. I understand his influence and it amazes me to see how the Jews have adopted his Torah even a thousand years after it was written.’ ”

The Rashi Institute

Every September 19, the Troyes town square hosts an unusual event: Some 1,000 city residents gather to mark “Rashi Day,” celebrated by municipal officials with great ceremony.

“It’s hard to understand what draws them to Rashi,” Joël Samoun says. “But in addition to their curiosity, there is a lot of admiration here for the leading commentator of the Jewish Talmud. Many intellectuals study Rashi here, writing articles, attending events in his memory, and giving lectures at what is called the ‘Rashi Institute.’ ”

The institute, which operates in Troyes as a branch of the nearby University of Reims, was established by the former French chief rabbi Rav Shmuel Sirat, with the intention of making Rashi’s memory accessible to French students and researchers. There are weekly and monthly lectures about Jewish thought. One course is called “Rashi and His School,” in which the students learn about the history of the Jewish Talmud and the influence of Rashi’s commentary.

The results are surprising: Most of the students who registered for the institute, which works with the Troyes shul, were non-Jews seeking to learn about the Torah, Rashi’s methods, and his unique form of writing. (This, despite the fact that Rashi played no part in creating this script.)

“The one who helped Rabbi Sirat to establish the institute was the mayor of Troyes then, Robert Galley,” Michel Amar says. “Whenever Galley came, he introduced himself as ‘the mayor of Rashi.’ ”

Another subject studied at the institute is the Dreyfus Affair, the anti-Semitic libel conjured 120 years ago against French Jew Alfred Dreyfus, who was accused of spying for the German Empire. Dreyfus was convicted and sent to exile, until a movement of intellectuals, politicians, and senior cultural figures managed to prove his innocence. This incident was etched into France’s national memory, and frequently comes up whenever anti-Semitism rears its head even today.

Before we leave, Bokobza and Samoun relate that efforts are being made to have the Rashi commemoration site recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

“If that happens,” Bokobza says, “it could mean that the French education ministry will include Rashi’s history in the curriculum. And then we may see a big change in the treatment of French Jews. We see small-scale influence already now. The moment it becomes public domain, it will literally be a revolution.”

So French schoolchildren could come to know the same Rashi that cheder yingelach have been learning for 900 years. Better late than never…

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 874)

Oops! We could not locate your form.