In Every Generation

A Judaica collector's wine-stained treasures from a lost world

Photos: Esky Cook

You’d think the brick colonial home on this residential Baltimore block is just as regular as the others lining either side of the street — until you step inside. Then, your senses are accosted by an impressive private Judaica collection that bears witness to centuries of Jewish life and survival.

This isn’t really a museum, though; it’s Eli and Ronnie Schlossberg’s home. Eli is a Baltimore community activist, executive trustee of the Ahavas Yisrael tzedakah fund, president of the Castle Consulting Group that specializes in kosher and specialty food distribution in the US and Israel, and the author of The World of Orthodox Judaism and My Shtetl Baltimore. He’s also a Judaic art and silver collector, but we’ve come here to see some heirloom items even more precious to him than his collection of dozens of ornate silver pieces.

Because for all his collectors’ items, what makes all those efforts most worthy is his treasury of many priceless heirlooms that he tracks back to his grandparents and their German kehillos (William and Lani Goldschmidt of Limburg, and Emanuel and Bluma Schlossberg of Fuerthe). In a time when people were leaving their valuables behind as they fled for their lives before the onset of World War II, both the Goldschmidts and Schlossbergs were miraculously not only able to escape Germany before it was too late, they were even allowed to ship containers of their belongings to their eventual homes in America. Eli and his sister Aviva Sondhelm, a music teacher in Jerusalem’s Har Nof, inherited the collection from their parents, Fred and Greta Schlossberg — every item of which opens another door into a lost world.

Let There Be Light

As we exit the foyer, the first room we see is Eli Schlossberg’s large private library (although he’s not an official collector of old seforim and manuscripts). But it’s the two centerpieces suspended from the ceiling that catch our attention — brass lighting fixtures from a bygone era. Originally hung from the Goldschmidts’ ceiling in Limberg, Germany, the dining room chandelier used oil instead of wax candles (wax was used by the extremely wealthy). The Shabbos candelabra is also different from the Shabbos neiros commonly found in most homes, as residents of Limberg would hang it on a chain and fill the cups with wicks and oil, a fixture found in old Yerushalmi homes as well.

Search the Attic

The Schlossbergs’ living and dining rooms are filled with breakfronts bursting with mostly silver devorim shel kedushah — over 80 pieces of silver besamim holders, menorahs, Kiddush cups, and esrog boxes.

While most of the silver pieces are new additions, there are a few treasured heirlooms that have their own special story attached — such as the Kiddush cup and Torah yad that made it through the war.

“In 1938, life in Limberg was getting increasingly dangerous for the Jewish community,” Eli relates. “Concerned with the rising cases of anti-Semitic behavior, members of the shul gave William Goldschmidt — my grandfather — the shul’s cup and Torah yad to hide for safekeeping. This was Providential, because the shul didn’t survive the Kristallnacht riots shortly after the handoff.”

As Nazi thugs went door to door abducting men and shipping them off to concentration camps (at the time these were labor camps and not yet explicitly extermination camps), Mr. Goldschmidt hid with the items in his attic. When the Nazis came to their door and demanded that Mr. Goldschmidt get on the truck, Mrs. Goldschmidt tried to stall for time, claiming he wasn’t there. She was offered two choices: Either they find him in the house and shoot him in front of her, or she lets them know where he’s hiding and his fate will “only” be deportation. Facing an agonizing decision, Mrs. Goldschmidt brought her husband to the Nazis, thus saving his life (the Nazis meanwhile helped themselves to many of the family’s valuables). Mr. Goldschmidt was arrested for his “crimes” and sent to Buchenwald that night — he was miraculously released after six weeks.

Years later, Mr. Goldschmidt’s progeny had a halachic question regarding the items the shul had entrusted to Mr. Goldschmidt before Kristallnacht. After all, it was never intended for him to keep them, but there was no shul or community to return them to. After taking the matter to a posek, it was ruled that the family needed to “redeem” the items by donating money to the German kehillah in Baltimore. Instead of being locked up in a museum, or displayed as antiques, the cup and the yad are still used by the Schlossberg family for the mitzvos they were crafted for.

A Gantze Megillah

Eli pulls out two more family heirlooms from the breakfront: One is a 250-year-old Megillas Esther scroll that belonged to his mother, passed down from the Austerlitz family, his great-grandparents. The Goldschmidts used the Megillah in Germany, and brought it with them when they immigrated to America. Greta Schlossberg (nee Goldschmidt) received it from her mother in 1948, and Eli’s father used it until 2002, when it was passed on to Eli.

“When I got it from my parents,” says Eli, “it needed repair, so I had it restored, and now it’s a hundred percent kosher. I’ve had it appraised at about $4,000, but I wouldn’t sell it for a million.”

The Schlossbergs also have Greta’s childhood Megillah — a rare Rodelheim Megillas Esther — which was published in Austria in 1925.

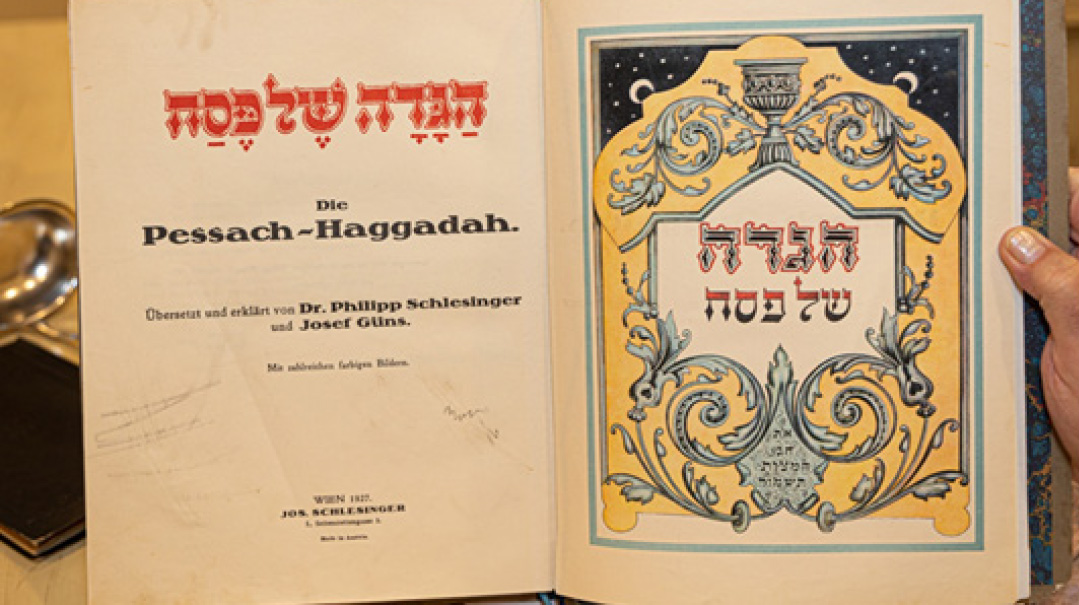

Retelling the Story

The Schlossbergs believe that items created for mitzvos should still be used for mitzvos, regardless of their age and antique value. Eli shows us an illustrated Pesach tapestry in their dining room that the Goldschmidts hung as a wall decoration for their Pesach Seder. The wall hanging depicts the 15 steps of the Seder, starting from Kadesh and ending with L’shanah Haba’ah BiYerushalayim.

“A century later, we’re still taking it out and using it. It’s like a ‘set,’ together with my mother’s Haggadah,” Eli says. “She received it from her father as a gift — its illustrations are as vibrant now as they were when it was printed nearly a century ago. If you look closely at the pages, you can see wine stains from Sedorim long past — showing that some things never change.”

While the Haggadah is around 100 years old — not considered a valuable antique by collectors’ standards, it’s priceless to the family because of the pieces of family history that it contains. Tucked away in the back is Greta Schlossberg’s birth certificate (the original certificate had the name her parents chose — Gretel — but in 1938, Hitler required all Jewish females to have the name “Sarah” added to their birth certificate, so it was changed).

The back pages of the Haggadah contain Greta’s handwritten personal history, her own yetzias Mitzrayim. She writes how she was sent to England on a Kindertransport as a teenager in 1938 to escape Nazi Germany, and describes her successful efforts to facilitate her parents’ emigration as well. Her parents (together with this Haggadah) arrived in England in August 1939, just a few weeks before the war broke out. The whole family immigrated to New York shortly after (their ship survived an attack by a German torpedo boat) where they remained until 1941, when they moved to Vineland, New Jersey, where Eli’s grandfather, a Jewish refugee, was able to afford a large farm.

Determined to ensure that her family’s minhagim were not left behind, Greta even wrote down the scores of her community’s niggunim, including the German Shir Hamaalos, which was always sung at the end of a wedding ceremony. She also included her father’s Pesach Seder niggunim and nusach, such as V’hi She’amdah, Nishmas, and the piyutim “Ki Lo Na’eh” and “Ein Lemmchem, Ein Lemmchem” (“Chad Gadya”). Thanks to her meticulous review, the niggunim were transmitted to her children and grandchildren.

The Haggadah contains one additional item of family lore: a letter from Eli’s maternal grandfather congratulating Eli’s parents on their newborn daughter, and inviting the young family to spend the next Seder with them on their farm in Vineland.

Cash and Carry

“My grandfather saw the writing on the wall and knew that Hitler was either going to throw them out of the country or kill them,” Eli recounts. “He wanted to prepare for his family’s escape, but he was not allowed to smuggle large sums of money over the border. So, he decided to use the German trains. My grandfather boarded a train bound for Holland, and while he was on board, he took a wad of deutsche marks and stuck it under his seat with a thumbtack. He disembarked at the stop right before the border. The train then continued into Holland — with no alarms raised as there wasn’t a Jew onboard. My great-uncle, his brother, then boarded the train in Holland and collected the money.

“And how did his brother find the money? It’s one thing to know which train to board, but how do you check under hundreds of seats without raising suspicions? Well, after he stashed the money, my grandfather took another thumbtack and stuck it under the wooden railing that was parallel to the seat that had the money. His brother walked down the whole train and when he felt the thumbtack under the railing, he knew the money could be found under the adjacent train seat. They were able to do this stunt three or four times, and smuggled out the equivalent of $4,000.”

Eli’s great-uncle unfortunately did not survive the war. But the money that was smuggled out was crucial in guaranteeing Mr. and Mrs. Goldschmidt’s visa from Germany to England.

“In 1938, after my mother left her family behind in Germany and escaped to England, her parents wired her that they needed to leave immediately before the gates would lock on them. My mother was able to get the bank statement from Amsterdam showing they had funds, and with that, she attempted to get an appointment with the new American ambassador to London — noted anti-Semite Joseph Kennedy, who was serving a two-year stint overseas. She had to visit his office three times before he graced her with a meeting.

“My mother said, ‘I need a visa,’ and used the bank statement to convince Kennedy that her family would not be wards of state. According to family lore, Kennedy was moved by the teenaged Greta’s unusual charm and beauty, and signed the affidavit.”

It was no small feat, as Kennedy would constantly refer to Jews as “kikes” or “sheenies,” and allegedly told embassy aide Harvey Klemmer, “Some individual Jews are all right, Harvey, but as a race they stink. They spoil everything they touch.” When Klemmer returned from a trip to Germany and reported on the assaults on Jews by Nazis, Kennedy responded, “Well, they brought it on themselves.” (It soon became clear to Washington that Kennedy, who advocated for appeasement and negotiations with Hitler, was completely out of step with President Roosevelt’s policies, and he was recalled from his diplomatic post.)

Eli says he later had an opportunity to relay this story to Joseph’s son Senator Ted Kennedy and granddaughter Kathleen Kennedy Townsend (Robert Kennedy’s daughter), and both were quite surprised that he willingly helped a Jewish family.

Record Keepers

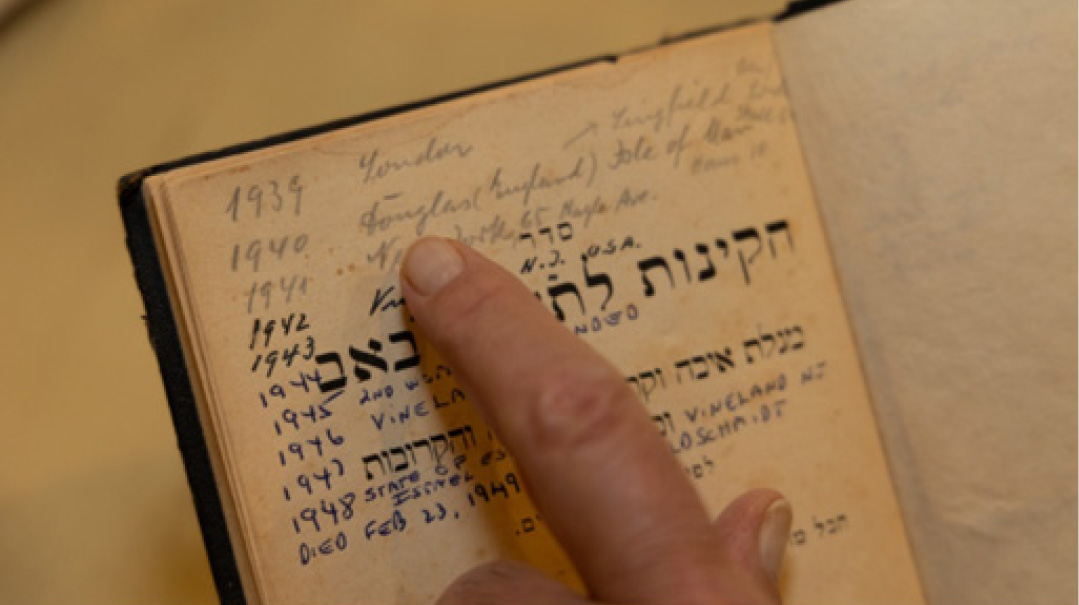

While traveling from Germany to England, and then from England to America, Mr. Goldschmidt always kept his copy of Tishah B’Av Kinnos on hand. He received it when he became the shul’s gabbai back in Limberg (which is likely why he was entrusted with the Kiddush cup and the yad).

“I believe that the Kinnos brought him comfort, and the contents were especially relevant during the time of Hitler,” Eli says.

From 1929–1938, Mr. Goldschmidt recorded the times of tefillah and who received aliyos at Minchah on Tishah B’Av. After 1938, he started to write his personal historical account:

1939 — Escaped to London.

1940 — Douglass, England: incarcerated on the Isle of Mann-Stall 64.

1941 — Went to New York.

1942 — Went to Vineland.

Greta continued to write the annual family history after the death of her father in 1949, and Eli took over after his mother passed away in 2016.

The Sounds of Music

In the Schlossbergs’ music room, Greta’s lute is prominently displayed. Over 100 years old, the instrument was purchased in Giessen (a town near Limberg). After finishing 8th grade, Greta wanted to attend music school, but around 1935, the Nazis were cracking down on Jews attending school under the guise of “preventing overcrowding.” Angry and disappointed, Greta went on a “piano strike” and refused to play at all. To placate her daughter, Nana (Greta’s mother) bought her the lute and signed her up for private lessons from a nun.

Opa Fred Schlossberg’s Bechstein upright piano was purchased in the 1920s in Fürth, Germany. Amazingly, the Schlossbergs were able to ship the piano along with furniture and other belongings as they fled Germany in 1939. The rule was that no one could leave with money, and only old and damaged belongings were allowed to be taken. So Eli’s grandparents purposely scratched some new items to qualify. Eli’s family has the harmonicas that his paternal grandparents shipped, and the piano was passed on to his sister Aviva.

My Castle

The Schlossbergs have dozens of small assorted artifacts that show slices of Jewish daily life in pre-war Germany, like these wooden barrels with dice, given as gifts to those who toured the kosher winery of the Austerlitz family (Eli’s mother’s grandparents), located in the town of Giessen.

There is also an original volume of the sefer Avnei Eish — a Hebrew and German sefer that was found in many homes, containing a detailed description of several hundred Jewish graves that were in the city of Eisenstadt. Among them are many tombstones of the Austerlitz family. It’s an important record today, as the beis hachayim was targeted by the Nazis.

There are many other pieces as well — a silver esrog box, a wooden Seder plate, a silver pocket watch picturing Moshe Rabbeinu holding the Luchos. More than arbitrary collectors’ items or display pieces collecting dust in a curio, these pieces are tangible items connecting one generation to the next.

“I have a large general Judaica collection that’s primarily made up of beautiful silver pieces including menorahs, a very heavy and ornate Seder plate, many besamim boxes, Havdalah sets, a silver train, many Kiddush cups, and esrog boxes — a very eclectic assortment of beautiful artifacts I cherish for their beauty. I have wonderful oil and water colors and Judaic paintings on every wall,” says Eli, who is a known and enthusiastic patron of Jewish artists. “Schlossberg in German means ‘Castle Mountain’ and my home is literally my castle.

“But these artifacts are different. They tell the story of a family who not only saved their precious possessions, but even more important, kept and saved the precious mesorah of their forefathers,” Eli continues. “They brought their mesorah to these shores and taught it to their children. May this mesorah continue through our own children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1006)

Oops! We could not locate your form.