In a Flash

| February 17, 2021“We Israelis are a country of survivors. And in the mode of surviving, we’re always looking for unique solutions. It’s just something in our DNA”

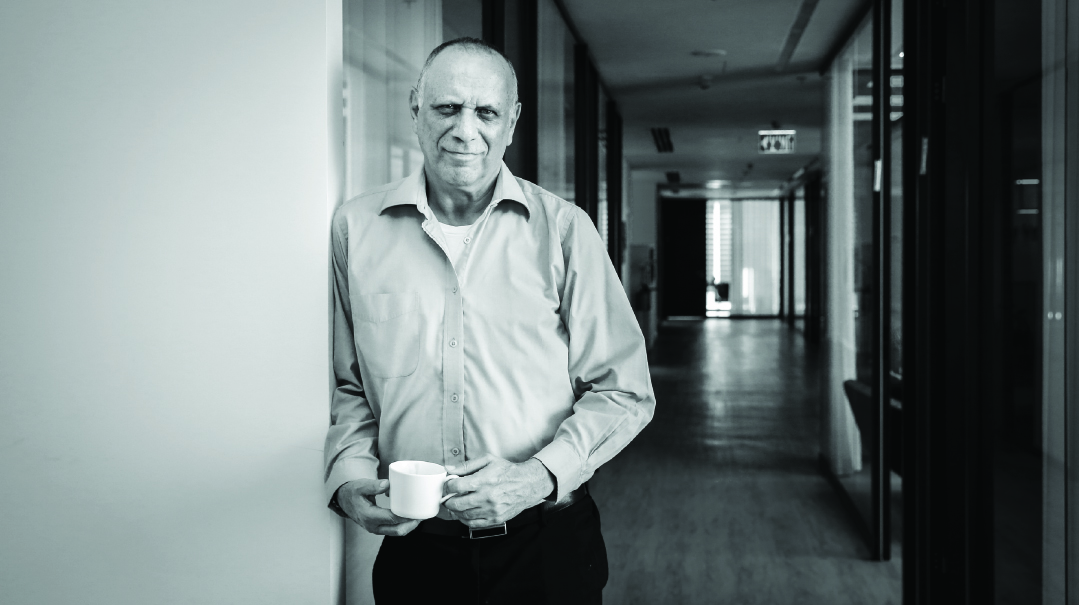

When you picture what today’s top high-tech inventors were like as children, you probably imagine some little genius taking apart an old radio and rebuilding it into some kind of postmodern device while his parents immediately sign him up for accelerated university courses. Well, international high-tech personality Dov Moran — inventor of the USB flash drive, the Flash-based storage for cellular phones, and other life-altering patents — wasn’t one of them.

He was a hard worker in school, not, he says, one of those natural-born geniuses, and his path to fame and success was paved with failures and disappointments, but Dov Moran never gave up. Maybe it has to do with his general outlook on life: When he’s asked to describe himself in one sentence, he says, “I’m one of the happiest people in the world.”

Despite his vast wealth and fame though, Moran, a father of four and one of the most prominent Israeli high-tech leaders in the world, remains modest and unassuming. We met in his Tel Aviv office to hear about his path — how it all started, and what lessons he’s learned over his 30-plus years as an entrepreneur, inventor, and investor.

“A lot of inventors are born geniuses, but not me,” he says. “I’m very much a late bloomer. I remember coming home with my report card in first grade and facing my parents who were sitting on the couch in the living room. I said, ‘Don’t worry, there was a kid whose report card was worse than mine.’

“But somehow, I always knew that I was going to be an entrepreneur — it’s how I grew up,” he continues. “My grandfather, a Holocaust survivor from Poland, was a successful businessmen back in Europe. I’ve always had this drive to be a part of making the world a better place, and innovation is what really drives the world and makes it better. It’s about trying new things and also about being willing to fail. I’m always asking myself, how can I make this thing better? If I see a problem, instead of ignoring it, I always try to find a solution. Sure, intelligence is very important for this, but I would say emotional intelligence is even more important — at the end of day, you need to intuit people’s needs. Entrepreneurs often spend time researching technology and investing in better marketing strategies, but they forget that the most important thing is to always put people first.”

Moran, who grew up in a Torah-observant home, earned a degree in electrical engineering from the Technion, was commander of the Israeli Navy’s advanced microprocessor department, and worked as an independent consultant in the computer industry, formed his first startup in 1989. M-Systems, a pioneer in the flash data storage market, was created, he says, almost by accident.

“At the same time, we were working on projects in flash data storage, and were considering developing a product in the field. A group of investors turned to us to ask how much money we would need for it. Without thinking too much I threw out a figure, $300,000, fully expecting that they would turn us down. But that same day they notified us that they had accepted the offer, and that’s how it started. Did we realize that something big would come of it? Not really. We didn’t have a clue.”

The company invented the FlashDisk (DiskOnChip), the USB Flash Drive (DiskOnKey), as well as several other innovative flash data storage devices. Moran reveals that he got the idea for the USB stick when he was supposed to give a presentation with his laptop, which died with all the presentation material inside.

Moran was 34 when he founded M-Systems. Ten years later, the company’s revenue was $45 million, and in 2006, after its revenue rose to over $1 billon, he sold it to SanDisk, an American memory card producer, for $1.6 billion.

At the time, though, he didn’t see the deal as a major success. “It wasn’t like my big dream to sell the company and make a splash exit,” he says. “I had very mixed feelings about it.”

Discovering a Better World

How does a kid with the worst grades in the class morph into a brilliant high-tech entrepreneur who’s among the most influential figures in the international technological industry? If you ask Moran, the answer is hard work. “It didn’t come easily,” he admits. “I was born so-so, but I worked hard. I’m curious, creative, an entrepreneur by nature. I love technology and science, and that’s what drove my career and successes. Looking back, I knew barely anything when I founded M-Systems. But I’m always learning, always improving, and when I move up, I try to help everyone around me move up too. I still hear from people about how amazing it was to work in M-Systems, and I’m really proud of the company, the people in it, and the journey we made.”

Following dozens of patents in the field of data storage infrastructure technologies, having founded and sold another high-tech startup, and having served as chairman of several companies in the Israeli electronics and bio-medical industries, in recent years, Moran has turned his attention to bankrolling other startups. He currently heads Grove Ventures, a venture-capital fund which invests in early-stage startups. He’s also written the book 100 Doors - An Introduction to Entrepreneurship, and gives lectures around the world.

Along the way, Moran admis, he’s encountered many obstacles and difficulties. In 1993 he came against an economic recession in Europe that affected many foreign currencies, he struggled through the dotcom bubble in 2001, and barely weathered the world crisis caused by the stock market crash in 2008.

“The high-tech industry took hits but always recovered, and I too always managed to survive,” he says.

The 2008 crisis left Moran especially heavily affected. The year before, Moran founded Modu, which developed a new modular phone concept which became the model for Google’s Modular phone project, and won a Guinness world record as the lightest mobile phone in the world. But when the credit crisis struck just one year later, the fledgling company had a hard time raising money from investors [it was an investment, not a loan, and part of it was Dov’s own money]. In 2010 the company was forced to close and fire its 130 employees. After the appointment of a new receiver, the company sold its patents to Google for just $5 million, and most of the investors’ money was lost.

Despite that, Dov Moran retained his tremendous motivation and infectious optimism. “The road to success doesn’t follow a straight line,” he says. “It’s not made up only of successes. There are upticks and downturns, but in the end, in the big picture, everyone is better off.”

What about the way the coronavirus has affected the tech industry? Moran remains optimistic there, too. “We haven’t had a global calamity for many years. Centuries ago, there was the Black Death, and the last century alone saw two world wars. There have always been catastrophes that wiped out significant percentages of the world population. For a long time, I was living with a feeling of impending disaster, like some major calamity was around the corner.”

It’s not a world war, but the coronavirus, for its part, has affected every branch of the Israeli economy. The airline, hotel, entertainment, and commercial industries are all tied together, and can bring each other down in a chain reaction. Moran believes the new high-tech companies will be the first to collapse, but older ones will also suffer. “This is a worldwide economic crisis that will affect every single one of us, but I’m convinced that just as we recovered from other blows over the years, we’ll rise from this too to discover a better world.”

To the Next Level

Although Dov Moran doesn’t describe himself as religious, he wore a kippah in his youth, and his wife was chozer b’teshuvah. “I feel a lot of pain for those who truly don’t believe,” he says. “Without faith, what’s the meaning of everything we’ve been developing? People set themselves all kinds of fictive goals: earning money, traveling the world, but none of these goals can create meaning, they can only create momentary pleasures that vanish without a trace. We have a mission to turn this world that Hashem created into a better place. For me, that gives life meaning.”

Moran has close to 60 inventions to his name, but looking back, he has a hard time explaining exactly why some of his inventions — such as the USB flash drive — had international success while others, such as the modular cellular phone of Modu, imploded. Today, as head of a venture-capital fund, he comes across hundreds of inventions each year, but only invests in two or three. The first thing he looks at, he says, is the inventor’s personality.

“A company in which people don’t get along with each other won’t succeed,” says Moran. On the human level, he searches for the three Qs: IQ (Intelligence Quotient), EQ (Emotional Quotient), and AQ (Adversity Quotient). First and foremost, what’s needed is an intelligent and competent team with shared values. EQ includes ability to communicate with colleagues, to recruit and manage employees, and to deal with suppliers and clients. At the end of the day, you also need high AQ, which displays as maximal functioning under pressure and pivoting with unexpected change. “A startup by its nature is always on the rise,” he explains. “But there are always obstacles that are getting more difficult the higher you climb. You fall and get back up, you get a lot of rejections, and to survive the journey, you have to be part of a team that can function well under stress.”

If your team is sound and your idea is truly unique, says Moran, then you can move onto the next level — to learn about the competitors, understand the market, and attain a deep understanding of the potential customers and their needs. Successful companies such as Mellanox, Mobileye, and Check Point, to name a few, are companies that have passed all these markers.

So what’s Dov’s best advice to aspiring entrepreneurs? “Never stop learning. The tool kit necessary for an inventor or developer in high-tech includes a lot of knowledge. Without knowledge, you’re limited. Choose your field, improve your knowledge of it nonstop, keep your eyes open all the time, keep abreast of changes, and don’t be afraid to act.”

No Complaints

Moran says he learned his best lessons from his grandfather. “My zeide, Avraham Mintz, was an amazing entrepreneur in pre-World War II Poland, where he lived with his family and seven children,” he relates. “He lost his parents when he was six years old, and at a very young age he started to build himself up. He established a locksmith workshop, a flour mill, a mercantile bank, a business for marketing mechanical devices, a cutlery factory, and several other businesses. He was also an inventor. In fact, there’s a museum today in his native city of Krosno, and one of the items on display is a water pump that he had invented and created.”

During the war, Avraham Mintz lost his wife and all his children and grandchildren, save for one son, Baruch — Dov Moran’s father. “But all that didn’t break him,” Moran says. “They came to Israel in 1949, where he continued to innovate. He said he did it for his soul and not for the money. And I can tell you that he was a happy man, and never complained or became depressed over what was lost and gone.”

In fact, his first invention upon arrival to the Holy Land was something still in use today: the ubiquitous metal garbage dumpster, known colloquially as a “tzefardeia (“frog”). At the time, the dumpsters were made of wood, which of course would rot and smell. Avraham Mintz wasn’t even trying to market anything — he just wanted his neighborhood to smell better.

“When I was little,” says Moran, “we lived in a tiny apartment in Ramat Gan. There was the living room which doubled as my parents’ bedroom, my sisters’ room, and then there was Zeide’s room, where I also slept. He slept on one side of the mattress and I slept on the other.

“Zeide’s supreme goal was to prepare me for life. He never said that to me directly, but he would always scout out various little jobs for me. For instance, he once instructed me to go into a neighboring building that was about to be demolished and take apart the window shades, which were relatively new, and replace the window shades in our building, which were old and falling apart. He once even showed me how to prune a tree that was bothering the neighbors. It was important for him to see that I was industrious and good at different things. When I look back, I see his fingerprints on all my successes.”

There’s something else as well. “We Israelis are a country of survivors,” he says. “And in the mode of surviving, we’re always looking for unique solutions. It’s just something in our DNA.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 849)

Oops! We could not locate your form.