Chance of a Lifetime

When Scott Woodrow heard the call, he couldn’t say no.

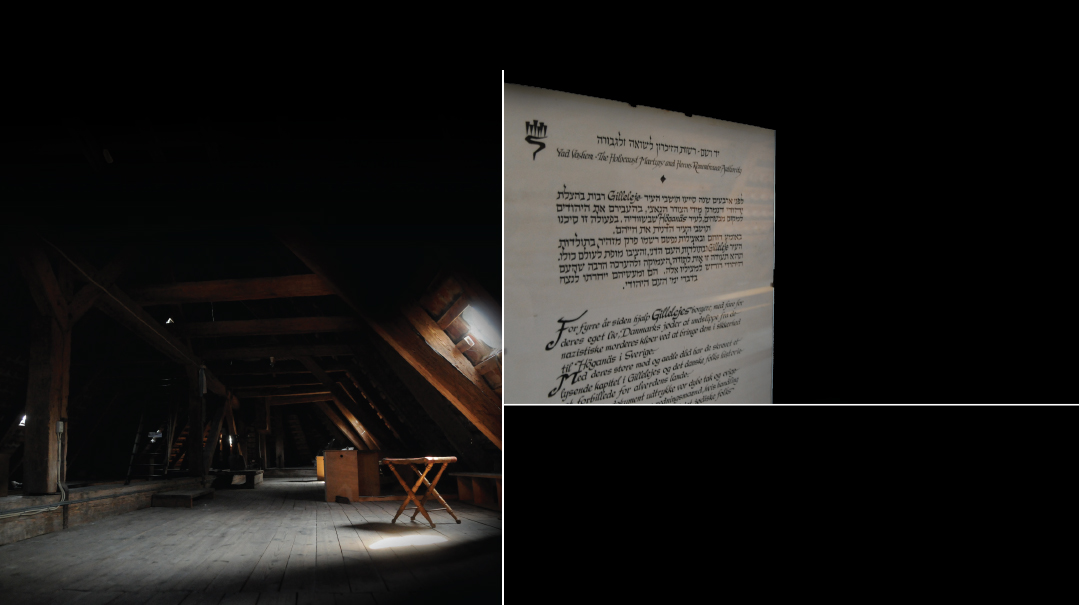

(Photos: Nechama Laitman Photography)

A little boy was in need of a liver transplant and Scott Woodrow stood ready to save him.

It was a typical leil Shabbos evening three years ago. After davening the gabbai ascended the bimah and announced that someone in the community needed an immediate liver transplant. Scott couldn’t be sure at that moment but he had an inkling the person in need was Aryeh the son of a rabbi at a neighboring shul.

For several years Aryeh’s parents had been searching in vain for a cure for their boy’s disease. They had consulted doctors conferred with gedolim b’ Torah and davened constantly. Their son’s illness had gone through a long series of twists and turns and life-and-death decisions. Finally the doctors told the rabbi and rebbetzin that Aryeh needed a new transplant.

Scott went home after shul and talked about the case with his family. The gabbai had said that the donor need only be healthy have a Body Mass Index of less than 25 and possess the right blood type. Growing up in a home with a father who gave blood regularly Scott already knew his blood type: He was an “O ” a universal donor.

Scott prides himself on his zrizus the quality of running to accomplish a mitzvah. The very next day he called the organization in charge of the transplant and first thing Monday morning he hurried to deliver the donor application to the hospital. As he walked there he felt a sense of urgency with each step.

He knew that being approved as a donor is a multi-step process so he told the hospital staff that he was ready for a test at a moment’s notice. “Don’t worry about scheduling ” he told them as his office was around the corner. “If there’s an opening I’ll come in and do it.” Like a businessman pursuing an ambitious deal Scott wanted to be the first person to perform this particular mitzvah. In the end his zrizus paid off. Before too long he found out that he would be donating part of his liver to Aryeh the rabbi’s son.

On a Search

Scott grew up in Vancouver British Columbia in a non-observant home. The family knew that they had at least one famous ancestor the Maggid of Mezeritch — but that was all in the past. His parents were loving and supportive and his home life was stable. But something inside him was stirring.

A contemplative person by nature when Scott was 16 he began reading books in his quest for purpose and meaning. He chose something from the classics Homer’s Odyssey and read a book on Taoism. And then there were a couple of Jewish books: a Chumash with an English translation and Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan’s The Living Torah. Every night before bed he’d take one of these books off the shelf and peruse a line or section that might light a spark.

On one particular night he happened to take the Chumash off the shelf and opened it to the story of Yosef and his brothers. When he arrived at the passage where Yosef now viceroy of Egypt reveals himself to his brothers 16-year-old Scott Woodrow began to cry. And not just a whimper. He began to cry uncontrollably and Scott couldn’t understand why.

Yes, Yosef’s revelation is certainly one of the Torah’s more dramatic moments. Yosef, no longer able to contain himself, clears the room of all his Egyptian underlings and finally cries out: “I am Yosef! Is my father still alive?” Still, Scott wondered why this particular passage, among all the Torah’s dramatic sections, so moved him. After all, his own life had been sedate compared to the turmoil of Yosef’s. He struggled to understand it, but failed.

As the years went by and Scott’s Torah observance blossomed, the mystery remained. He married and started to raise a beautiful family in a frum home, sending his kids to Torah schools. Their home was open to guests, especially those who were new to the idea of keeping the mitzvos. At the Shabbos table, guests would ask Scott how he came to be observant, and he would tell them the story of reading the Yosef story as a teen and the intense feelings that overcame him. The guests always had the same question: Why that story?

Time went by, and Scott and his wife Devorah were blessed with four children. He started and ran two businesses, davened every day with a minyan, and made time to learn Torah. He felt the tremendous blessings that Hashem had bestowed upon him. Then came the gabbai’s announcement and the opportunity to bring his gratitude to an entirely new level.

Just a Beginning

After a much shorter waiting period than usual, Scott was approved as a donor. This, of course, was only after convincing the hospital’s psychiatrist that he was of sound mind. After all, who would voluntarily give up part of his liver to someone he hardly knows? “Have you seen any visions or apparitions that told you to do this?” the psychiatrist asked him. Scott, in pain from an earlier test, told the psychiatrist not to make him laugh — it hurt.

“No, it’s not a psychotic episode,” Scott told him, offering an explanation that the medical man might understand. “In a world that is so inundated and so preoccupied with violence and hatred, the only thing that we can do to combat that is to do the exact opposite and engage ourselves in extreme acts of kindness and love.”

To himself, he added. “That’s the tikkun (the fix).”

The surgery was scheduled for a Tuesday in December. At the rabbi’s shul, large gatherings were called to say Tehillim, both for Aryeh and for Scott. Scott’s children, who backed him in the decision, knew that undergoing major surgery involved some risk. The night before the operation, his 11-year-old daughter asked him: “Daddy, what if this is the mission that Hashem has for you in life and, once it’s done, Hashem takes you to Shamayim?”

Scott hugged his daughter and told her, “If I do make it through, then it means that I’m not done yet and that this is just a beginning. There are so many more things we will be able to do.”

The liver is a highly vascular organ, attached to the body by a huge number of veins and arteries. Taking out a piece is not a simple procedure. The surgery, in which doctors took out 20 percent of Scott’s liver, took eight hours. Incredibly, most, if not all, of his liver will grow back.

A runner who keeps himself fit, Scott progressed through the recovery process quicker than most. But it was still a wallop to his body. He was in the hospital for five days and then slowly built himself up with short walks near his house, using a cane. It was a few weeks before he could go back to work and two or three months before he was back to himself — albeit now with a scar running from his ribcage to his belly button.

For the little boy, the recovery was tougher and longer, but, baruch Hashem, the doctors regarded the surgery as a success. After a tough winter isolated at home, Aryeh went back to school, joining his friends in the schoolyard and living the life of a normal boy. Yes, there had to be a bit more caution with his immune system. Yes, he still missed a few days of school here and there. But he could now focus on all the same things as his classmates: toys and snow forts and Shabbos parties and learning the aleph beis.

Bound Up as One

Scott first returned to shul on the Shabbos of Parshas Vayigash. He wanted to get back to davening in a minyan and to feel that special feeling of being in shul on Shabbos. He also had another piece of business to accomplish: He had to recite gomel. And to do that, he decided to daven at Aryeh’s father’s shul.

The gabbai knew that Scott, a Levi, was set for the second aliyah. Scott followed the Torah reading closely in his Chumash during the Cohen’s aliyah. He started to feel butterflies in his stomach as he realized there was something special about this moment. Yehuda was in the middle of telling the viceroy of Egypt why Yaakov’s youngest son, Binyamin, must not be left in Egypt. His father, Yaakov, already bereft of his wife, Rachel, and her older son, Yosef, had only Binyamin left from her. Without Binyamin, Yehuda explained, Yaakov could not go on living. “Nafsho keshura b’nafsho,” the Torah’s words about Yaakov and Binyamin, were the final words read just before Scott was called up. “His soul is bound up in his soul.” The words made Scott think about Aryeh and the connection they now had.

As Scott recited the blessing on the Torah, his eyes teared up and his knees felt weak. He stood at the Torah and watched through tears as the little silver yad passed over the words revealing that the ruler of Egypt was also among the children of Israel. “I am Yosef. Is my father still alive?” The words unleased an emotional torrent. Could it be? It was this very same story that had released an emotional flood 26 years earlier.

Suddenly, he understood why he had felt so strongly reading this particular pasuk so many years earlier. He now knew that Hashem had given him a siman that night, hinting at this Shabbos morning. Because he had picked up the Chumash and read that story on that evening, he had begun a journey that led him to becoming observant, which in turn had led him to move to the frum community, which led him to the right place at the right time to hear the announcement that would allow him to save Aryeh’s life.

Out of the 54 parshiyos in the Torah, and the seven aliyahs into which each one is divided, it was this one on which he would bench gomel. As he began making the brachah, he was overwhelmed with a deep new layer of kavanah. He wasn’t only thanking Hashem for the physical delivery from surgery. He felt at that moment as if he was also thanking Hashem for the spiritual delivery that had brought him to Torah and his life of overflowing brachos. He was saying gomel not only on the danger that had just passed but also on his physical and spiritual redemption.

After the davening ended that Shabbos morning, he hurried to tell the rabbi what he had finally discovered. As he approached, the rabbi, of course, thanked Scott once more with all his heart.

On the contrary, Scott said, he wanted to thank the rabbi.

“I feel,” said Scott, “like I just won the lottery.”

*name has been changed

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 690)

Oops! We could not locate your form.