If There’s a Will… with Allan Gibber

| June 13, 2023The legal and halachic ramifications of not having a will are complex

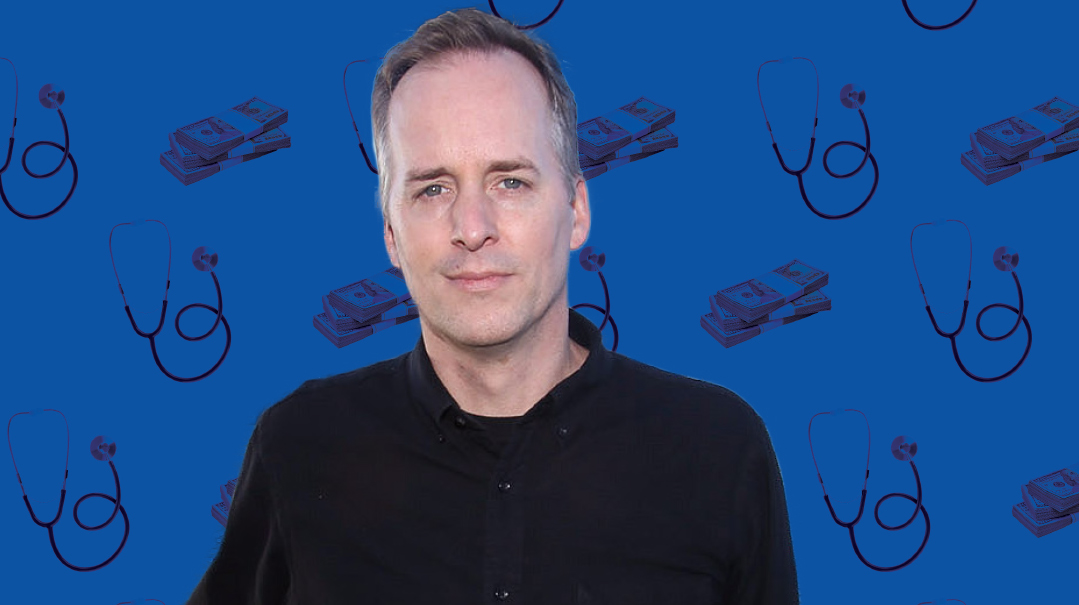

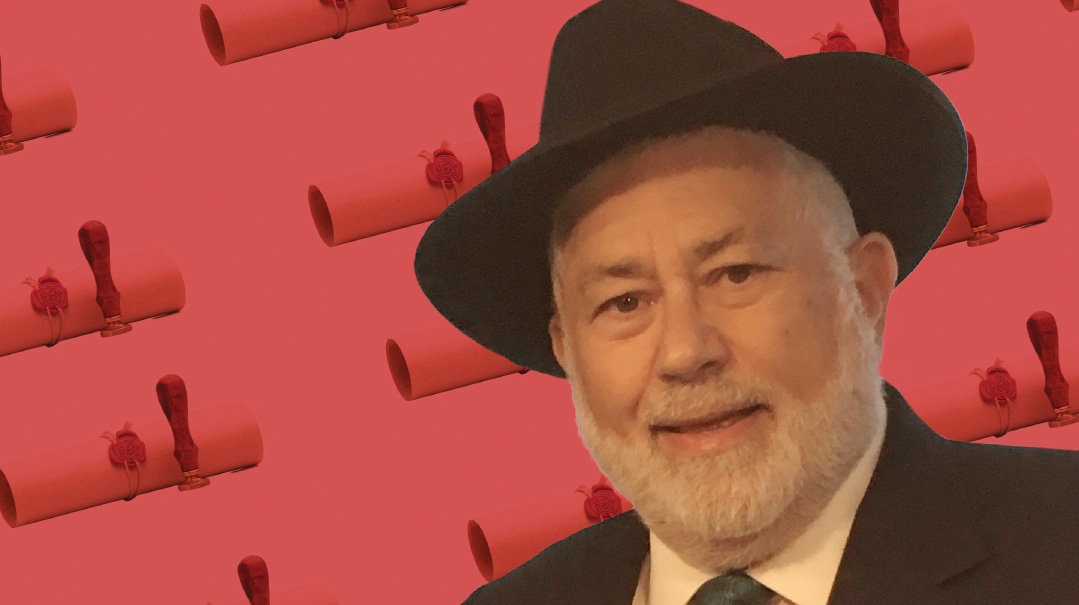

“Nothing is certain except death and taxes.” It’s been centuries since Benjamin Franklin came up with this famous axiom, but it still holds true, and few people are more acutely aware of that than Allan Gibber, a Baltimore-based estate and trust attorney for more than 50 years.

People mistakenly assume that if they don’t have mega millions to protect, they don’t have to prepare a will, and figure they will just leave everything to their spouse.

But burying one’s head in the sand never helped anyone, and the legal and halachic ramifications of not having a will are complex. Halachically, there’s a set process that details what each relative inherits. Legally, there are contradictory laws that might end up overriding the halachos. A clearly delineated will is the surest way to guarantee your wishes will be followed when you’re no longer around to ensure they are.

In Gibber’s decades in practice, he’s been involved in all types of estate planning, asset protection, and estate tax preparation. His experience has been codified in Gibber on Estate Administration, a textbook covering estate-related legalities. In this episode, he shares with Kosher Money and Mishpacha readers the vital importance of preparing for the day after, despite people’s natural reluctance to do so.

What does every frum family need to know about writing a will?

Know that you must address these issues. No one knows what tomorrow will bring, so look out for your family by having a plan in place. It’s true the plan may need to be adjusted every few years, but that’s infinitely better than having no plan at all. No one wants to accept that death can catch someone unprepared, but it can, and you’re doing your family a great disservice if you don’t address it in advance.

Does everyone need a will, or is that only for those with serious assets to protect?

This is one of the biggest misunderstandings I see. Everyone needs some kind of legal plan in place. Even if you’re not too concerned about your assets, you still need a will to protect your children and to dictate your medical wishes, among other such vital topics. It’s very shortsighted to think a will is only about money. If something happens to both parents, G-d forbid, what happens to the children?

If you don’t make a plan, the questions will be answered in court with the default law of that state. If you want to do things in your own way, you need to make that clear so the court will follow your wishes. No one wants the courts to decide who will raise their children.

In addition to asset planning, make sure to designate a power of attorney, a medical directive, and plans for your children. If you don’t put a plan in place, there’s a chance that the courts will rule differently than how you would have wished.

What is a medical directive, and why would someone need one?

A medical directive is essentially a living will saying, “This is how I want to be treated and X is the one designated to make those decisions.” Often people will add a line saying that those decisions need to be made in accordance with halachah.

The main reason it’s vital is because this is how you can communicate your end-of-life preferences. In the Orthodox world, this is critical; if you don’t have a plan, you will be subject to your state’s laws regarding end-of-life care, and they may completely contradict Jewish values.

Legally, a person has a right to say, “I want to live,” but the default law probably doesn’t support that. Unless a patient has legally stipulated otherwise, medical personnel may decide to pull the plug or allocate available resources from one patient to another they deem as having a better chance of making it. Not having a medical directive is a disaster waiting to happen.

Another important point to keep in mind is that while you may appoint only one specific family member to make decisions regarding your care, do yourself a favor and make sure everyone else still has HIPAA release. Let every child be entitled to call the nursing station and find out how Dad’s doing. When children have to rely on one sibling for updates, it creates breeding grounds for disharmony.

In the podcast, you mentioned that there are legal and halachic ramifications when someone dies without a will. Can you elaborate?

If things aren’t worked out in advance, there’s going to be a lot of tension where the halachic and legal ramifications intersect. Halachically, for example, the oldest son gets a double share of the inheritance. But what if there are minor children involved, and the remaining parent needs those funds to raise them?

Halachically, a wife doesn’t inherit at all; instead, she gets her rights from the kesubah, and a daughter also gets less than a son.

There are workarounds if someone wants to leave his estate to his wife, or to all his children equally. Rabbeinu Gershom was the first to suggest changing the system and ensuring that daughters get a share, too. He did it by creating a document outlining his “debt” to his daughters. When someone passes away, his debt is paid before the estate is divided, so his daughters were given a portion [as “creditors”], and then the sons divided the rest.

There’s also a workaround with which the oldest can be moichel his share in favor of his mother or sibling. But if the oldest is still a halachic minor, he doesn’t have the ability to be moichel. The parent would then not be able to access that money and use it to help raise the child.

I’ve also had cases where the business belonged to both spouses, and then one died. So what happens? Who inherits the business, the spouse or the oldest child? Does the surviving spouse lose her income in favor of her children? It becomes a real, real issue — and often causes a lot of family conflict.

Bottom line is, halachah doesn’t grant a person the right to control where his property goes after he dies. So if a person does want to do something other than the halachic default, he needs to address that while he still can.

Can a will override the default halachos of inheritance?

Yes. The Gemara talks about this and explains that while a person is still alive, he can designate his property as a gift that he will give to the beneficiary the moment before he dies. That’s one halachic resolution.

If you want to go this route, you need to make a kinyan for the gift to be halachically valid. Rav Moshe Feinstein said that the process of giving the papers to the lawyer establishes a kinyan, so if it’s legal, then it’s likely to be halachically valid as well.

What happens if someone doesn’t do this “matanah” or kinyan process?

If a person doesn’t have a will, there’s absolutely nothing that can be done that will allow for his estate to be divided other than the way halachah dictates. And that can be a pretty serious issue, especially if there are young children. You need to have a will, or there’s nothing beis din can do to help your children. They have no legal standing, so they can’t override the secular courts. Your estate will follow the secular system, and there’s nothing your family will be able to do to help divide it in accordance with halachah.

Technically, the daughter can waive her right in secular court — but what if she doesn’t want to? What if she wants to retain her portion? Is she “stealing” from her brother because halachically it’s his? With no will, there’s room for a whole host of problems.

And these are real issues that should force a person to say, “Listen, this might make me uncomfortable, but at the end of the day, I have a family, I need to protect them. I’m going to put everything in place.”

If parents don’t yet have a will in place, how can their children gently broach the topic?

Good question. Look, it’s scary for people to face the possibility of death. The best way to bring it up is to focus on the life aspect. These papers protect the parent while he or she is still alive. A medical directive is to protect the patient so that the patient’s desires are met.

And we’re not only talking end-of-life. What happens if someone’s in surgery and you need to make a medical decision on his or her behalf? Who can do that?

Say it directly. “Listen, we’re family. We need to know what it is that you want — and you don’t have to tell us, but it has to be someplace we can find, if and when it’s necessary. We’re all coming to you because we want you to do it in a way that will prevent issues. If you want to leave a legacy of shalom, here are things you can do right now to prevent any disunity.”

Where do you see things go wrong?

Power of attorney is where we see the most abuse. It’s a very tricky position, because the designated child is given the right to make legal decisions on behalf of the entire family, and while the one with power of attorney may think she’s acting with a parent’s best interests in mind, the siblings can feel like she’s skewing things in her own favor.

When there’s real diversity or adversity between the siblings, things inevitably end up in a major battle.

On the podcast, you spoke about trust funds. Can you break down the different trusts and how people know which is best for their family?

A trust is equivalent of an entity, so if I put an asset into trust, it’s no longer my asset — it belongs to the trust. I appoint somebody to oversee this and then I give directions on how it should be distributed, invested, or dealt with.

Setting up a trust is hard, because many people are just simply not emotionally prepared to start moving things out of their own name. It feels uncomfortable. But it offers some very strong protections to ensure that what you want to happen after you’re gone gets done.

There are two main kinds of trusts:

Revocable: I retain the right to change my mind

People may have the mistaken belief that a revocable trust has a tax consequence, but that’s not true. It doesn’t make taxes higher and it doesn’t make taxes lower. If you want to do tax planning, this is not the trust for you.

Putting funds in a trust is usually more effective than allocating them in a will. For example, in New York, the probate process is woefully slow. We’ve had estates that took more than a year to start moving through courts. If you want to avoid going to probate and at the same time have the advantage of keeping your assets private, put your assets in a trust.

No one ever does this, but if someone were to theoretically put their entire estate in a trust, there would be no need for courts at all. The trust is a testamentary document that takes the place of a will. There are many states in which a trust is really highly recommended, because it’s a simple way to deal with assets and avoid long waits or high expenses.

Trusts are also valuable for people with property in other states. If you live in New York but own in Florida, you’d need two separate legal processes. But if the out-of-town property is part of an in-town trust, then it becomes a local asset and you can deal with it in local courts.

Irrevocable: I cannot change anything about this

These are commonly used when people have assets above a few million. If you leave significant assets to someone else (ranging from $6 million to $13 million, depending on local laws), they’ll have to pay high taxes. If you separate yourself from the asset, then it’s not part of your estate and the heirs get a discount on those fees. They don’t have to worry that the government will first take a generous helping.

When someone passes away, how does their family know where their assets are?

Ideally, the deceased would have created a list of all their bank accounts, investments, and assets. That way nothing will get lost when they’re gone.

If someone did not create that, the next best thing is to keep an eye on their mail, especially around January and February time, when every financial institution is sending out information with tax details or updates. If you sort the mail, you’ll likely find indications of assets you didn’t know existed.

It’s not as good a plan as it used to be, though, because everything’s going paperless. That’s why the list is so important. I know someone who had a business that was 100 percent online. When he died, no one had access to it, and the companies refused to let his family in because it was a privacy violation. You don’t want to be in that situation.

By nature, dealing with a will is often fraught with tension. How can families avoid drama?

MONETARY ASSETS

I’ve done it a lot of different ways, and we’ve addressed it with a lot of different people. The first thing is to make a distinction between the active participants and the inactive participants. If your children were active in the business with you, to what extent is their sweat equity part of the value of the business? Is the business really fully yours to give away, or do they have a portion of it from their work?

Most people want everyone to have a share, but think about what makes most sense. Maybe you give the active participants their equity and then look at giving different assets to children who were not involved in the business. Maybe one child runs your business and another runs your foundation. You want to make sure people feel like they got their fair share so they’re not resentful.

It won’t work to say, “Here’s the business. The son is running it and the daughter gets a portion of the profits.” The daughter is going to see her brother driving a fancy car — where did he get the money for that? Oh, it’s a business expense? That’s cutting into her profits. What you get then is tension, tension, tension.

So to answer your question, the best way to avoid drama is to analyze the people, analyze the assets, and analyze the opportunities that they present. Then create a plan that has the least possible room for battle.

People on all economic levels are scared to talk about death. And as a result, they hesitate to question, “What happens when I’m not here?” I had a client who was a Harvard graduate and CEO of a Fortune 500 company — and he died without a will. How is that possible? How can a person with all that education and experience neglect to look after his wife and kids?

Nobody knows what tomorrow brings. If something happens and you don’t have a plan in place, chances are things will not go the way you would have wanted. Always have these prepared:

Power of attorney

Health care proxy

HIPAA release form (so parents and children are entitled to medical updates)

List of your assets (so it’s possible to find everything after death)

Child care directives (so minor children are cared for)

If your medical directive specifies that you want to follow halachah, make sure to include the name of a rav. Otherwise, your children will each ask their own rav and you’re back in the same situation with four different opinions and opportunity for machlokes.

Financial literacy does not come through osmosis. It either comes from well-taught lessons or from experience. It’s always going to be better to learn in preparation than to learn the hard way when you end up in a frightening situation.

Once you draft your will, review it either every five years or after every major life change.

PERSONAL BELONGINGS

It’s interesting. Usually, the less valuable an asset is, the more people fight. People have an emotional connection. “I gave that to Mommy, so I want it back,” not realizing that if you gave it, it’s no longer yours, and you have no more right to it than your siblings.

There’s only one menorah, one set of tefillin, one leichter… how do you deal with that? This is the place where I urge parents to make a plan. I’ve found that when children see their parents were trying to be fair, they rarely argue. They might not like it, but they accept it. But don’t leave it to your children to work out by themselves.

For parents: Before you go and make anything in your estate other than equal, you must know that you have to really think long and hard about it. Is it worth it? Make a plan that keeps everyone in mind, and once you do, you need to communicate it.

I’m not in favor of sharing the contents of your will as soon as the ink dries, because that limits your flexibility to change it. But at some point, make sure everyone understands why you did things the way you did.

For children: Whatever happens, peace is the goal. You might have to take interesting approaches, like selling off property to redivide it, but if everyone is focused on peace, then you’ll come up with creative solutions.

People don’t need to know you chose them as your power of attorney in advance. That will only make it complicated if you choose to change your mind. Your family just has to know where these directives are so they can find them when they need them. Don’t share the paperwork — but let your family know where it is.

I’ve never written an ethical will where the first line didn’t mention, “My dear children, I want this to be done in a way of shalom.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 965)

Oops! We could not locate your form.