If Not for My Rebbi

The boy had never heard of Kamenitz or its rosh yeshivah but he took his new friend up on the offer

The boy had never heard of Kamenitz or its rosh yeshivah but he took his new friend up on the offer

He was the rebbi. He was the talmid.

Few figures lived both titles to their fullest as did the Kamenitzer Rosh Yeshivah Reb Boruch Ber. His shiurim masterpieces of depth and profundity are still the surest path to lomdus the introduction for many a hard-working bochur to the thrills of becoming a yeshivahman. Yet he maintained the reverence and awe of an eager young talmid for his own rebbi Rav Chaim Brisker even after he took his rightful place on the Eastern Wall of the Lithuanian Torah world.

He was a man of lekach (scholarship) and of libuv (heart) the very soul of the Torah. A man of tears and of song of poetry and prayer.

And today seven decades after his passing ushered in an era of unprecedented suffering for our people a new world has risen in which those three words -- “Reb Boruch Ber” -- have again come to symbolize the totality that can be attained through toil and tearful supplication.

There are not many left who remember the great man who heard him deliver the legendary shiur or sing heartfelt zmiros at his Shabbos table. Not many who saw the luminous face crowned with the immense yarmulke framed with the wild white peyos.

Rav Moshe Chaim Sapochkinsky doesn't just remember: he carries those memories before him in his heart and soul. For as he puts it ever so simply “If not for my rebbi I wouldn't be here today. I owe him everything.”

Rabbi Sapochkinsky is a sprightly vibrant man bright blue eyes twinkling with vitality and gentle humor. He is the rav of one of Montreal's most historic shuls the Nusach Ari shul founded by his late father-in-law with a group of Russian Yidden and a respected shochet. And perhaps unlikely for a Kamenitzer talmid he is a distinguished Lubavitcher chassid. “That is where my rebbi sent me ” he says.

A most intriguing story ...

On a Chair in the Woods

Rabbi Sapochkinsky was born in the Polish hamlet of Suvalk -- “a town with not one chassid.”

The Divine Hand that kept young Moshe Chaim from harm was evident in the summer of 1938 when he was fourteen. His mother was suffering from arthritis and was advised by her doctor to spend the summer months in the healing air of a resort town Druskenik.

What the words Cape Cod do for a blue-blooded American does the name Druskenik do for a student of the prewar yeshivah world. While Druskenik doesn't evoke memories of balmy lazy summer days at the beach it conjures up a yearning for a “Druskenik summer.” The resort town was the gathering place for budding scholars -- a place to share argue and deliberate the fine points of a Rashba or a nuance in the Rambam with the best and brightest of the other yeshivos.

Its proximity to Vilna and Grodno made Druskenik the summer home of many gedolim: Rav Chaim Ozer Rav Shimon Shkop Rav Aharon Kotler and Rav Boruch Ber spent their summers there as did many chassidic leaders. In fact it seemed that everyone wanted space in Druskenik. Every home became a hotel every kitchen a restaurant and the poor Jews of the town looked forward to the yearly economic boost during the summer months. Unwilling to lose the bnei yeshivah who had no connections or money the rav of Druskenik formed a committee to help every bochur find a bed in the town for the days of bein hazmanim and the tranquil streets would be filled with the sounds the passion and the energy of a beis medrash for those few weeks.

Moshe Chaim who was off from cheder was privileged to accompany his mother to enjoy the country air in Druskenik. As boys will do he went to the shul and soon found himself a friend another youngster his age. The two children spent a happy afternoon playing together.

The boy whose name was Yehoshua asked Moshe Chaim if he wanted to meet his grandfather.

“Who is your grandfather?”

“The Kamenitzer Rosh Yeshivah Rav Boruch Ber” was the reply.

The boy had never heard of Kamenitz or its rosh yeshivah but he took his new friend up on the offer. Together they walked into the woods where surrounded by a wall of pine trees Rav Boruch Ber sat on a striped beach chair engrossed in learning.

He looked up and greeted his einekel who introduced his new friend. Reb Boruch Ber greeted him warmly.

Over the next few days as Moshe Chaim and Yehoshua formed a deep bond Moshe Chaim spent more and more time in proximity to the holy Rosh Yeshivah. One day Reb Boruch Ber asked the boy where he learned. He replied that he had graduated cheder in Suvalk and would likely go the yeshivah in Lomza as did most of the boys in his hometown.

“Come learn by us Kamenitz has a wonderful yeshivah ketanah for boys your age and I will take care of you.”

The boy was intrigued and went to ask his mother. Mrs. Sapochkinsky made her way through the forest and approached the Rosh Yeshivah.

“Who will take care of him?” she asked.

“My rebbetzin will treat him like a son and we will ensure that he eats well and sleeps well.”

She wrote a letter to her husband asking his permission but he knew little of Kamenitz and the Rosh Yeshivha.

“But he asked the cheder rebbi in Suvalk Rav Zimmerman who assured him that Kamenitz was a 'good' yeshivah and he gave his consent. Months later when I came home for Pesach the rav Rav Dovid Suvalker greeted me excitedly wanting to know all about Kamenitz and Reb Boruch Ber. Only then was my father really convinced.”

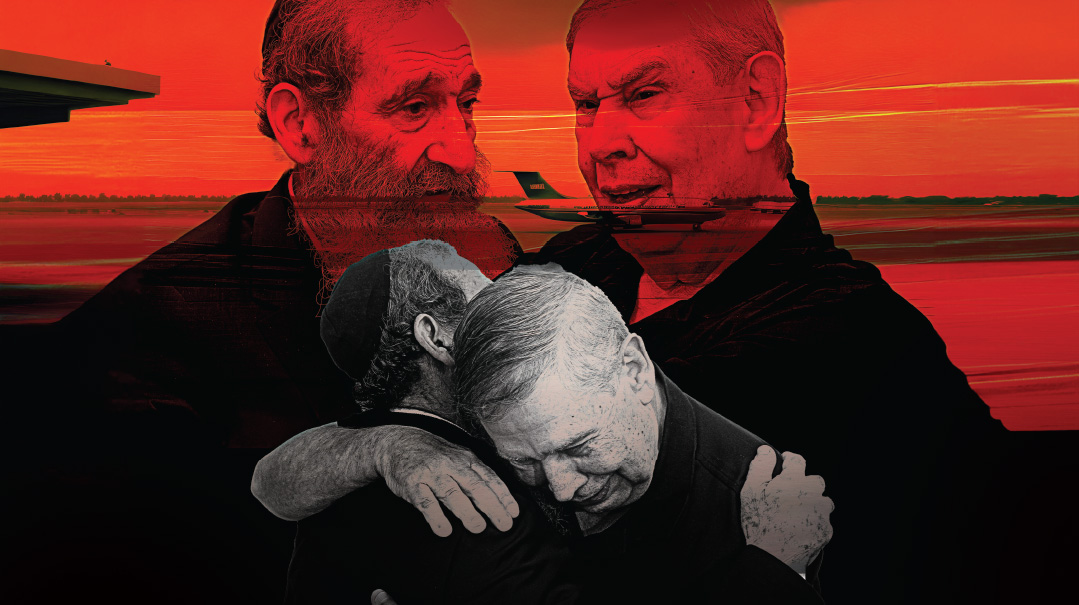

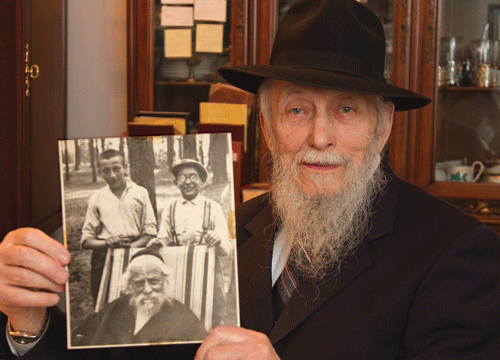

There is a famous picture of Reb Boruch Ber seated on his chair in the woods of Druskenik with two boys standing behind him. One is his grandson Yehoshua and the other in most books remains unidentified. Until now. It's the Jew with bright blue eyes sitting next to me Reb Moshe Chaim. He reaches into his wallet and withdraws the original showing me the handwriting across the back.

“This is my mother's handwriting it's all I have from her. What happened was that on that first day there was a photographer out there in the woods so Yehoshua and I stood behind his grandfather for a picture. My mother was so excited with it that she sent a copy to her brother in America with a note on the back. Later when I reached America I went to visit this uncle in Lowell Massachusetts. He handed me the picture a reminder of a simpler time the most peaceful few weeks of my life.”

And so when the vacation came to a close Moshe Chaim joined Yehoshua and his grandparents for the trip to Kamenitz. They took a train to Brisk and from there a wagon to Kamenitz. True to his word Reb Boruch Ber looked out for the boy throughout the trip.

Like a Son

“I moved into their home. They insisted, although there was clearly no room. Reb Yaakov Moshe Leibowitz lived on one floor with his family, and Rav Reuven Grozovsky and Rav Moshe Bernstein, the two sons-in-law, lived upstairs with their families. So Rav Boruch Ber and his rebbetzin had only the middle floor. In addition, my friend Yehoshua, his sister, and their widowed mother lived in one of the rooms on that floor, so space was at a premium. The rebbetzin set up a bed for me in the dining room, near the table where the Rosh Yeshivah sat and learned. I felt like I would never be able to sleep there. So they arranged a bed for me in a room with older bochurim from the yeshivah, but insisted that rather than eat ‘teg’ by the townspeople like the rest of the bochurim, I would eat with their family. Each day I ate with one of their children, and on Shabbos and Yom Tov I ate with Reb Boruch Ber and his rebbetzin.”

The young boy learned well in the Kamenitzer yeshivah ketanah.

“I was farhered by Reb Boruch Ber each week,” he laughs.

At the Shabbos meals, in which family members and other talmidim joined, the Rosh Yeshivah would go around the table, asking each one what they had learned that week.

“I remember how the house would fill with guests, but he was sitting at a desk engrossed in his learning, until the rebbetzin would call ‘Boruch Ber’l, come eat the seudah.’

The boy grew older, but he still hadn’t heard much about Chassidus or chassidim.

“I remember the first time I heard the word ‘Lubavitch.’ Kamenitz Yeshivah was filled with chassidishe bochurim, especially Gerrer and Alexander chassidim. Reb Boruch Ber loved every talmid, and there was no hint of machlokes or tension between the litvishe and chassidishe bochurim. I remember the impression made on me when, that first Pesach bein hazmanim, I watched Reb Boruch Ber bid farewell to each bochur. He would kiss them with such warmth, like a father who wouldn’t be able to handle the absence of his son. He loved each and every bochur that way.

“We had never really heard of any Chassidus besides Ger, and maybe Belz, but the last Shabbos before Pesach, a bochur ate with Reb Boruch Ber’s family. His name was Noach Minsker, and he told the Rosh Yeshivah that he would be traveling to his family in Riga, Latvia, for Yom Tov. Reb Boruch Ber, always eager to hear how Yidden were faring, asked him to please return to his house for a seudah on the first Shabbos after Yom Tov, so that he could hear a report about Jewish life in Latvia.

“Sure enough, Noach returned and delivered a full report on the schools and shuls of Latvia. Then he told about the head of the community, a chassid and member of the Latvian parliament named Reb Mordechai Dubin. Noach related that Reb Mordechai had a private minyan for Shacharis that took a full hour and a half.”

“The Rosh Yeshivah, himself a master of tefillah, was intrigued. Noach explained that Reb Mordechai was a chassid of Chabad, and that the Baal HaTanya wrote that a weekday davening should take no less than ninety minutes. Reb Mordechai, a true chassidishe Yid, davened in accordance with the Alter Rebbe’s direction, slowly and with great concentration.”

“Reb Boruch Ber was amazed. And that was when I first heard of Chabad!”

Der Heilige Rebbe

Rabbi Sapochkinsky tells me that Rav Boruch Ber loved to hear about ehrliche Yidden, and would often relate stories about his own rebbi and other gedolim with tremendous emotion.

“I was too young to attend or understand his shiur, but I would sometimes sneak in and stand in the back just to watch him. The main thing I remember is his passion when he said the words ‘der heilige Rambam’, ‘der heilige Rashba’, and, of course, ‘der heilege Rebbe.’ What an impression that made!”

I ask about the role that Reb Boruch Ber had in the goings on outside the yeshivah, in the town.

“He vehemently refused to pasken sheilos, to get involved in community affairs. ‘There’s a rav here,’ he would say, ‘ask him the sheilos.’ He was focused on the yeshivah.”

Yet, there were times when he stepped out of the boundary he set for himself. “When there were threats from the Haskalah or from one of the youth groups that were reeling in yeshivah bochurim, then he rose like a lion, refusing to allow them entry.

Reb Moshe Chaim recalls Rav Boruch Ber standing at the bimah in the large central shul, addressing the community after hearing that a group of parents in town were considering allowing a Tarbut school to open.

With great emotion, Rav Boruch Ber recalled that his yeshivah had originally been in Vilna, but he had decided that the impure influences were too strong there and he sought a quieter village. There were three towns that expressed interest: Kosova, Kamenitz, and Birza. He approached the Chofetz Chaim, who advised him to go to Kamenitz, where “there is a chazakah of Torah and yiras Shamayim.”

Then Rav Boruch Ber recalled his discomfort at the honor he was shown upon his arrival, how the townspeople unhitched his horses from the wagon and insisted on pulling it by themselves.

“I couldn’t handle the excessive display of kavod. But Reb Reuven assured me that you were sincere people, who just wanted to show honor for the Torah itself, not for me.”

Then, in a tear-choked voice, he continued:

“How can it be that you, the people of Kamenitz, are considering allowing a school to open where they will teach students to mock the Torah?”

His words found their mark, and the plan was dropped.

Reb Moshe Chaim points to a book, one of several biographical sketches of his rebbi, and says, “There are stories that no one knows, because no one was there. That summer in Druskenik, it was just Yehoshua and me and the Rosh Yeshivah. The Rosh Yeshivah is not here and Yehoshua was murdered by the reshaim … so it’s just me.”

Another memory from the summer.

“On Tisha B’Av, we davened in the shul in Druskenik. They would wait for Reb Boruch Ber to finish each kinnah, out of respect. But when he got to the kinnah of Arzei HaLevanon, which recalls the deaths of the asarah harugei malchus, he began to sob uncontrollably. He wept and wept, sitting there a full half-hour saying the kinnah before he felt capable of continuing.”

The young ben bayis would sometimes merit a special honor: walking the Rosh Yeshivah to the yeshivah.

“He would always need someone to walk him, since he didn’t lift his eyes in public, so sometimes I got the job of accompanying him, leading him by the hand. He would tell me ‘Moshe Chaim, if you see a policeman, tell me.’ If I told him a policeman was approaching, he would lift his eyes and raise his hand as a sort of salute. He felt it was important to make them feel respected.”

Another memory.

“One day, I was talking to him in the house, and I asked, ‘Rebbi, how does one attain yiras Shamayim? He looked at me with his pure eyes and said, ‘Durch gut lernen a Tosafos,’ through learning a Tosafos well.”

The primary memory that Reb Moshe Chaim has of those years is of Reb Boruch Ber sitting and writing what would become the Birkas Shmuel.

“He had this large notebook in which he wrote everything, and whenever you came in, he was either learning, speaking in learning, or writing in that big notebook. Lo pasak pumeih migirsa; he never took a break from learning.”

But that idyllic period would last just over a year.

To Vilna

On 17 Elul 1939, Germany invaded Poland and war broke out. Refugees from all over the country streamed into Kamenitz, taking shelter in the presence of the great man. Through the weeks of Tishrei, life in Kamenitz became increasingly difficult, as first German forces took control of it, and then the Soviets wrested it from their grasp. In the beginning of Cheshvan, news spread that the Soviet government was turning Vilna over to the Lithuanian government. Rav Chaim Ozer sent a message that Reb Boruch Ber was to bring his yeshivah to Vilna immediately. Reb Boruch Ber accepted the psak, and told his family to pack their bags and hire wagons.

Moshe Chaim had a dilemma. The yeshivah ketanah in Kamenitz, where he was studying, was staying put, because most of the talmidim were local boys who wanted to remain with their parents. Only the yeshivah gedolah was relocating to Vilna, but Reb Boruch Ber was going.

“You are coming with us,” Reb Boruch Ber decided.

“It was so hard for him to close the yeshivah and leave his beloved Kamenitz. He had only recently come from America with money for a spacious new building, and parting from his seforim was especially painful.”

Reb Boruch Ber parted from each volume with tears. Once again, as when he had arrived, the Jews of Kamenitz lined the streets and surrounded his carriage, but this time they weren’t dancing, they were weeping.

When this little group arrived in Vilna, Reb Boruch Ber inquired about an appropriate yeshivah ketanah for his own eineklach and, of course, for the boy, Moshe Chaim.

“He had a nephew in Vilna who was a maggid shiur at the Lubavitcher yeshivah, and he told Reb Boruch Ber it was a fine yeshivah.”

Reb Boruch Ber told Moshe Chaim and his two grandsons, Yehoshua Leibovitch and Chaim Grozovsky to go learn in Lubavitch. And that’s where Reb Moshe Chaim remained, until today.

“I was a young boy, and there was a mashgiach there, Reb Elya Moshe Liss, who treated me like a son.”

During his first few months, he spent lots of time at the home of Reb Boruch Ber.

“But then, at the beginning of the winter, he took ill. The pressures of the move and the heartache of the news from all around took its toll. His condition worsened for a few weeks, and then, suddenly, he was gone. It was the 5th of Kislev. We were orphaned.”

Reb Moshe Chaim puts it into historical context.

“This was a month after the petirah of Rav Shimon Shkop, and we felt like our protective wall was crumbling. Ten months later, when Rav Chaim Ozer left us, we knew that we were defenseless.”

He recalls the levayah and the tearful hespedim.

“Not only have we lost Reb Boruch Ber,” said the Baranovitcher mashgiach, Rav Yaakov Yisroel Lubchansky, “now we are also saying goodbye to Reb Chaim Brisker.”

The two grandsons of Reb Boruch Ber eventually left Lubavitch — Yehoshua traveled with the Kamenitzer yeshivah to Rassein, where he met his end at the hands of the accursed Nazis, and Chaim Grozovsky left with his family to Japan, and eventually reached America.

Moshe Chaim was on his own.

With the Chassidim

He spent the winter in the Lubavitcher yeshivah.

“The yeshivah was planning its escape, but I almost didn’t make it. My parents had left Suvalk, which was in Poland, and relocated to the Lithuanian town of Mariampole. I traveled to spend Shabbos with them. On Motzaei Shabbos, I received an urgent telegram that the yeshivah was setting out that night. ‘Come quick, we have visas,’ it said. They had obtained visas through the graciousness of Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese diplomat who was a shaliach [Hashem’s messenger] to save so many bnei yeshivah, and they had one for me as well.”

“I hurried back to Vilna as fast as I could, taking a train that rumbled on through the night. I arrived at the yeshivah in the early morning, only to find out that the yeshivah had gone and I had missed them. I rushed to the train station, well after the train was slated to have departed, and”—here Reb Moshe Chaim pauses and his voice trails off, barely a whisper—“the train was two hours late. I made it just in time.

“If the Eibeshter decrees that someone should live…”

He joined the fateful journey on the trans-Siberian railroad, crossing the continent and eventually reaching Shanghai, China.

“It was hard for us, the Lubavitcher bochurim, in Shanghai, because we were without a rebbi or maggid shiur. But we were chassidim … we tried to be mechazek ourselves.”

I ask if the Lubavitcher bochurim interacted with the other bnei yeshivah in Shanghai.

“There were different sections in the city, and one needed a permit to cross from one to the other — it was a war zone. I do remember that when a Mirrer bochur was niftar, nebach, we went to hear a hesped from the mashgiach, Rav Chatzkel.”

He recalls how some of the lions of the Mirrer chaburah would come learn in the Lubavitcher beis medrash during night seder, when it was dangerous for them to walk back to their shul. With a smile, he recalls one of the legends: Reb Shmuel Charkover, later rosh yeshivah in Beis HaTalmud.

“Being from Charkov, he had grown up around Lubavitcher chassidim and he was always lifting our spirits. In fact, he was the one who taught us the famous niggun for HaNeiros Halalu, which we weren’t familiar with. He brightened up a dark Chanukah for us with that song.”

America

Ultimately, Reb Moshe Chaim reached America, where he joined the Lubavitcher yeshivah in Crown Heights. “The rosh yeshivah was Rav Gustman, who I had learned under in Vilna, where he was also our rosh yeshivah.”

Reb Moshe Chaim had learned shechitah in Shanghai, and one day, a friend arrived in New York and told him that there was a need for qualified shochtim in Montreal.

He traveled north, finding not just a job, but his zivug: a daughter of the late Rav Yitzchok Isaac Yagod, who had served as a maggid shiur of daf yomi, Ein Yaakov and Mishnayos at the Nusach Ari shul, established by a group of committed and ehrliche Yidden, a rarity in the Montreal of the early twentieth century.

(Among the descendants of Rabbi Yitzchok Yagod are many illustrious rabbanim and maggidei shiur from Lakewood to Crown Heights; Monsey to Columbus, Ohio; California to New Jersey to Eretz Yisrael.)

Rabbi Yagod had passed away in 1940, and when Reb Moshe Chaim married his daughter, he began to daven in the Nusach Ari shul. The rav there, Rav Eframovitz, known as the Dvinsker Rov, was a talmid of the Rogatchover Gaon. When he was niftar in 1953, the shul administration appointed Reb Moshe Chaim as the new rav.

Reb Moshe Chaim assumed leadership of the shul while also serving as a shochet for the Vaad HaIr. When the Jewish community moved up from the old neighborhood, he led Nusach Ari from Pine Avenue and St. Lawrence up to its present location in the Westbury neighborhood.

He has led his flock for more than fifty years, bli ayin hara, fusing Kamenitzer scholarship with chassidishe spirit.

And he has never forgotten …

Throughout the years, he has kept his connection with the family of the gadol who took Moshe Chaim, a boy of fourteen, home with him.

“I maintained a close relationship with Rav Chaim Grozovsky throughout the years.”

Rebbetzin Sapochkinsky smiles and rattles off the Brooklyn address of the Kamenitzer Yeshivah, evidence of decades of addressing envelopes headed in that direction. On visits to Eretz Yisrael, the Sapochkinskys made a point of looking up the children, the daughters and daughters-in-law of Reb Boruch Ber who had survived and remembered the sweet little boy who was a fixture at the Shabbos table.

And now, as Reb Moshe Chaim Sapochkinsky says the words “hey Kislev,” the yahrtzeit of the Kamenitzer Rosh Yeshivah, he says it like a chassid, to whom the yahrtzeit of his rebbe is sacred.

“I listened to him and came to Kamenitz, where I was the child, the youngster. Now, I am the oldest, ‘miziknei anash,’ all thanks to him….”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 333)

Oops! We could not locate your form.