Ideas in Three Dimensions

Here is my relationship with comedy. I hope no frogs are harmed in the process

M

y editor and dear friend, Sruli Besser, called me last week to remind me to get my column in. He added one voice note (Sruli is on the UN terrorist list for his voice note usage) that we both knew would give me anxiety — “Make sure it’s funny, it’s the Purim issue.” At this point I think he feels bad for me. Every week I leave him some long-winded voice note (I’m also on the UN terrorist list) about how I have nothing. Some of my favorite columns were written in a near-fetal position, just to cope with the anxiety of getting it done. Because here is the thing about writing comedy: It’s tough. I’ve been doing this for over two years and now seems as good a time as any to reflect on what I’ve tried to accomplish. I know this is dangerous — if writing comedy is hard, writing about comedy is usually awful. E.B White once said, “Explaining a joke is like dissecting a frog —you may learn about it, but you wind up with a dead frog.” But Purim is an appropriate time to present the role humor and comedy has played in my life. So here is my relationship with comedy. I hope no frogs are harmed in the process.

1. Open Shtender Night

In elementary school, making jokes is associated with being the class clown. When you’re younger, the things that make you laugh are more slapstick. When I was in seventh grade, for example, the most reliable humor involved talking on the rebbi’s microphone when he stepped out of the room. The moment the rebbi would leave — and we knew this was a big no-no — the microphone would beckon the most mischievous kids in the class to try their best routines. It was a consistent crowd-pleaser.

But as we grow up, what makes us laugh matures as well. I don’t think I thought of myself as particularly funny until the end of high school — I was too insecure to try to make people laugh. But then yeshivah began. The economy of jokes in yeshivah is a drastic departure from elementary school. In yeshivah, a sharp line and a clever joke isn’t considered clownish — it’s part of being a lamdan. In every yeshivah I attended, it was always the strongest bochurim who starred in the Purim shpiels. During my time in Ner Israel, the Purim shpiel starred a current rav in Columbus, a rosh kollel in Chicago, and a Yeshiva-Laner in Ner Israel’s kollel. Yeshiva University was not all that different with their shpiel. The person who did the best impression of Rav Schachter was one of his star talmidim, and is now a fellow rosh yeshivah there. It wasn’t just the students — listen closely and you’ll see that rebbeim always have the best one-liners. I remember once during a chaburah in Rav Ezra Neuberger’s office, a phone of one of the talmidim started vibrating. Rav Ezra paused, clearly displeased by the disruption. “I think your shaver is on,” he said. The Chazon Ish once took a talmid to go swimming with him. While in the middle of the lake, the Chazon Ish began to splash. The talmid looked astonished. Splashing? The Chazon Ish responded, “If you can’t learn to play when you’re supposed to play, then you’ll never learn how to learn when you’re supposed to learn.” At the heart of my yeshivah experience was learning to swim in the Yam HaGemara. But part of learning how to swim is learning when to splash.

2. Comedy with Borders

About once or twice a week I get a suggestion for a Top Five list. Some are incredible, most are awful. The best one I ever received was from a girl in Lakewood who wrote a list of Top Five conversation topics guys use on dates. It was brilliant and, as I discussed in another Top Five, she obviously developed a pseudonym and fake email before sending. I’ve had roshei yeshivah send me ideas (Top Five times you clop in shul), I’ve had dorm rooms in the Mir send me ideas (something like Top Five ways to be shtultzy and geshmak — appreciated, but rejected), and I have a Top Five list of ideas Mishpacha will probably never let me publish. (Top Five characters at the mikveh on Friday is ready to go.) Ideas are usually rejected because they’re either not funny or not actually a list of anything — every time I use the word “weekend,” Sruli tells me there’s a Top Five in there somewhere.

But sometimes an idea is rejected because it’s a topic I’m not comfortable making jokes about. A while back a dear colleague, who also happens to be a wondrous wordsmith, wrote a column critical of Jewish humor that “zeroes in on the perceived idiosyncrasies — a more genteel word for inanities — of frum life.” “But this type of humor,” he writes, “has always discomfited me.” The writer recalls a time that he was distracted during Kiddush Levanah, considering the potential topics a humorist could develop with the scene. Different people may have different comedic tastes, the article concludes, but all humor writers need red lines. “Can we agree on the need for them to be drawn?” he asked. I undoubtedly have different tastes than this writer, but I completely agree with his concern. Comedy needs borders. One famous comedic producer put it this way: “There’s no creativity without boundaries. If you’re gonna write a sonnet, it’s 14 lines, so it’s solving the problem within the container.” I’ve never made jokes about davening — and there are plenty — but I’ll joke about trying to find a minyan on a Chol Hamoed trip (“outside the monkey cages, 3 p.m.”). I’d say the Top Five I’m most proud of was about the Tishah B’av practices we need to discard. It was delicate ground — I don’t think I would have attempted to broach the subject when I first started. The key question is always, what is the target of the humor? Humor is a deeply spiritual tool and it should never be aimed at sincerely. Constructive humor is spiritual, destructive humor is cynical. Sure, I’ve missed the mark. But I consider bringing joy to Jews about Jewish life a type of avodas hakodesh. Yes, there’s a Jew who thinks that after 120 years, one of his primary zechusim might just be his silly columns. It’s okay if that makes you laugh. That’s the point.

3. Searching for a Punch Line

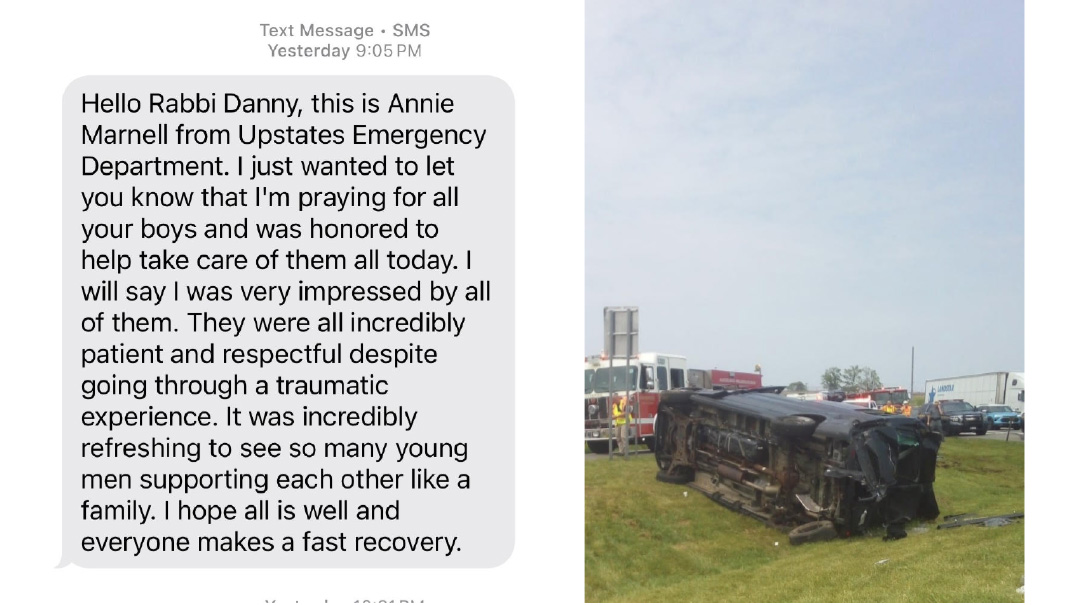

A hesped changed my view on comedy. In fact, that particular funeral changed a lot of things for me. My dear friend, Rabbi Josh Grajower, lost his wife, Dannie, after a long bout with cancer. I knew them both well, though for nearly a decade, Dannie insisted that her illness be kept private. Her death came as a shock. Josh gave his eulogy with one of his three children clinging to his leg. During this tragedy, Josh recalled Dannie’s incredible sense of humor — I knew her as well and was often the subject of her jokes. This is what he said — it’s a direct quote, with his permission:

When we came to New York for Succos, unfortunately we had to go straight to the ER. When realizing we would be stuck in the hospital all Shabbos, just the two of us, I grabbed two books to read. The first was Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Yes, an intense choice. It was actually Dannie’s copy of the book and she had underlined certain parts. One thing she underlined was a comment Frankl made about the surprising role of humor in concentration camps. He wrote the following lines about humor, and they were some of the few lines underlined by Dannie:

“It is well known that humor, more than anything else in the human make-up, can afford an aloofness and an ability to rise above any situation, even if only for a few seconds… The attempt to develop a sense of humor and to see things in a humorous light is some kind of a trick learned while mastering the art of living.”

Humor, the Maharal explains, is when we subvert the normal sequence of life. A well-dressed man in a suit is not expected to slip on a banana peel. We laugh when our normal sequential narratives are suddenly overturned. The setup for a joke establishes a sequential line of thinking — the punch line introduces the incongruity. Comedy and tragedy approach the same incongruous narrative, but whereas tragedy laments the lack of sequence, comedy creates its own story. I think about the power of comedy every year when we lein Megillah. During Megillah we have a curious custom of reading the words v’keilim mikeilim shonim (Esther 1:7) with the Eichah trop. As a kid, I always figured we did this to build the tension. It was like dramatic background music — “dun de dun dun.” But we don’t really do this during other sad stories in Tanach, so why here? I imagine Purim and Tishah B’Av as two old friends, who have experienced a lot of difficulty and pain together. After many years, Purim finally realizes his redemption and during the celebration he sees his old friend Tishah B’Av standing off to the side. On Purim we grab Tishah B’Av with both hands and bring him into the celebration. We remind Tishah B’Av that it’s a Purim still unfolding. Comedy and laughter have the power to subvert tragedy. On Purim we take all of our Tishah B’Av feelings and moments and bring them into the circle to dance along with us. We create a narrative arc so broad it provides comfort to our pain. If only for the day of Purim, we smile with all of the difficulties of life — mastering the art of living.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 801)

Oops! We could not locate your form.