I read it for you: Benjamin Graham

Each morning, Mr. Market knocks on the door and offers his stock at a different price.

W

hen I was in fifth grade, we played the stock market game. Each team of students was allotted an amount of money (this was not real money, much to my chagrin), and we competed against other elementary school teams to see who could make the most money over the course of a year in the stock market. I still remember our strategy. We opened up the newspaper with the stock quotes — in those days stock quotes could only be found in the newspaper — and we looked for the stocks that had the highest price and the highest percentage change the day before. The most expensive stock we found listed was Warren Buffett’s holding company, Berkshire Hathaway, then trading just north of $20,000 a share.

Unfortunately, we did not win the competition. Not even close. The winner was always the team that had students whose fathers worked in finance and provided some “insider information” (i.e., guidance) to their eager fifth-grade children. My team’s parents were doctors, and we would consistently land at the bottom. But I walked away from the competition with two lessons: I needed to find a better stockpicking strategy, and I needed to find out more about Berkshire Hathaway. As it turned out, both questions had the same answer.

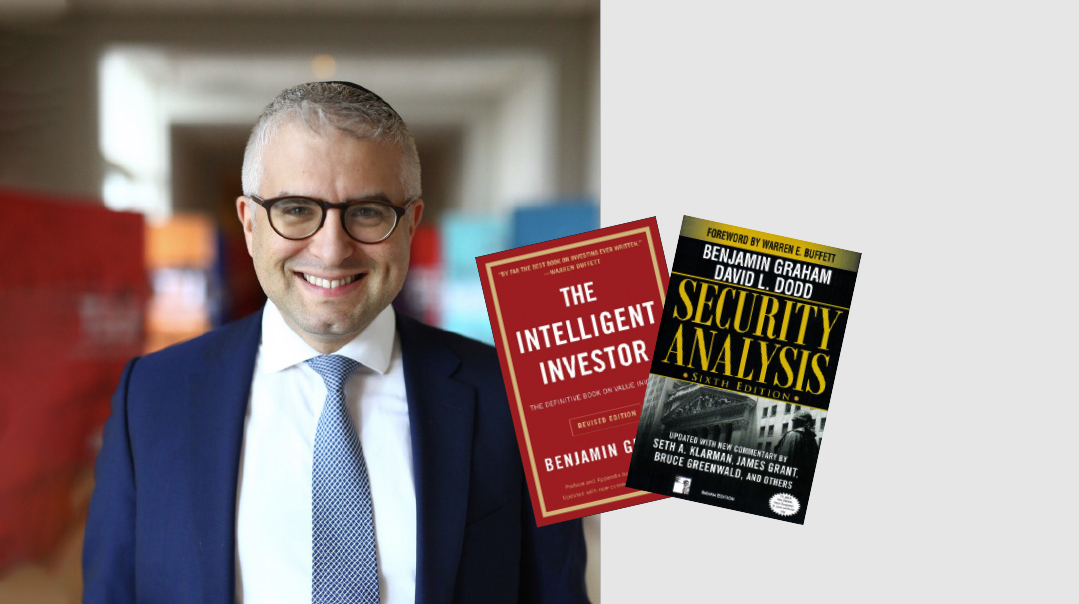

Warren Buffett, chairman and CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, has already become a legend even for those outside the world of finance. But he attributed his core investment strategy to a lesser-known figure, someone outside the investment world, a man named Ben Graham.

Mr. Graham taught Mr. Buffett in Columbia University and wrote two foundational books, Security Analysis (first published in 1934), which he wrote with David Dodd, and The Intelligent Investor (first published in 1949), both of which have become the bedrock for an investment approach known as value investing. The most important character in The Intelligent Investor is Mr. Market. Graham introduces a critical analogy to investment strategy that asks the reader to imagine a man showing up at his doorstep every morning. Known as Mr. Market, this man urges him to buy shares of his company. Each morning, Mr. Market knocks on the door and offers his stock at a different price. Sometimes it’s with excitement and enthusiasm, and sometimes Mr. Market seems depressed.

The entire premise of The Intelligent Investor is learning how to ignore Mr. Market and focus instead on the inherent value of the company. It’s simple advice, but not as easy to follow. In all aspects of our lives, it’s too easy to be convinced by Mr. Market. Consensus, group-think, passing trends, and the like are difficult to ignore and sometimes even harder to identify when they’re the operating force in a decision. The suspicions with which Graham asks us to treat the wares of Mr. Market are as necessary for the stock market as they are in our personal and religious lives. Trends, however exciting, do not yield long-term value. So, how is true value found? For this you may need to read Graham and Dodd’s more academic text, Security Analysis.

While it differs in some ways from his later work, The Intelligent Investor, the book lays out the principles for determining what he calls the “intrinsic value” of a company. This practice, known as fundamental analysis, projects the fair value of a company based on the discounted value of their cash flows. In layman’s terms, this refers to how much money will be returned from the ownership of this stock to the shareholders, factoring in the time value of money (otherwise known as discounting). Fundamental analysis, of course, is part science, part art. The key indicators for a company’s long-term health may be hidden deep within their balance sheets. This book shows you where and how to look for such value. Instead of buying stocks from Mr. Market, Graham challenges his readers to buy from companies with intrinsic value that will provide long term financial wealth.

As his student Warren Buffett has said, “Our favorite holding period is forever.” To be sure, fundamental analysis is not the only way to assess value or make money on the stock market. Some technical traders prefer the manic nature of Mr. Market, and rather than finding value in mispriced companies, they take advantage of market momentum and price fluctuations. Others, such as Eugene Fama, a notable American economist, have challenged the very foundations of fundamental analysis. According to Fama’s theory, known as the efficient market hypothesis, most stocks already have their future growth and potential prices in view, so finding mispriced stocks is unlikely, bordering on impossible. Regardless of the approach one takes in his or her financial life, there are certainly life lessons to be gleaned from Graham’s works. Value can be specious, but focusing on intrinsic value can make life richer.

Rabbi Dovid Bashevkin, director of education for NCSY, teaches Jewish Public Policy at Yeshiva University’s Sy School of Business and is currently completing a dissertation in public policy at the New School, focused on crisis management. His book, Sin•a•gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought, was recently published by Academic Studies Press. He has been rejected from several prestigious fellowships and awards.

(Originally featured in 2.0, Issue 4)

Oops! We could not locate your form.