Hungarian Hospitality

| May 2, 2023How Reb Shayale's descendants welcomed 35,000 visitors to his historic house in Kerestir

Rebbe Shayale Kerestirer fed every lost, broken, or wandering Jew who came to town, serving up miracles of salvation for dessert. A century later, travelers from around the world are partaking of the blessings

Rabbi Mendel Rubin remembers the first time he went to visit the tziyun of his great-great-great grandfather, Rabbi Yeshaya Steiner ztz”l, known to the world as Reb Shayale of Kerestir.

Growing up, Reb Mendel’s father, Rav Shaye Rubin, the Kerestirer Rebbe in Williamsberg, traveled every year to northeastern Hungary to mark Reb Shayale’s yahrtzeit on the third day of Iyar. But it was only in 2003 that 18-year-old Mendel joined his father on the pilgrimage, making his first trip to the village of Bodrogkeresztúr, better known as Kerestir.

Even now, two decades later, he can still remember his father’s tear-stained face as they approached Reb Shayale’s ohel.

“Everything you are going to beg and be mispallel for, you are going to have, so don’t hold your tears in,” he told his son.

Walking into the ohel was like entering a different world, remembers Reb Mendel. It was small, tiny even, with low ceilings. Stepping into the room, the bochur pulled out his Tehillim and started to daven.

“I said a few kapitelach, and I couldn’t anymore,” recalls Reb Mendel, just hours after returning home to Monsey last week from a pilgrimage to Kerestir for Reb Shayale’s 98th yahrtzeit this past 3 Iyar. “I started crying and crying. And that was my first experience going to Reb Shayale.”

Welcome Home

In his lifetime, Reb Shayale, who was born in 1851, earned a reputation as a miracle worker. A chassidic rebbe in the Hungarian village of Kerestir, he was beloved and revered for his kindness and humility, with the doors of his home at 68 Kossuth Utca always open to all.

From impassioned chassidim who doted on his every word, to lost souls searching for a place to call their own, everyone was made to feel welcome in Reb Shayale’s house, where a seemingly never-ending supply of food and drink was dispensed at all hours of the day and night. The downtrodden, the forlorn, the struggling, and even the lice-infested were all treated like royalty by Reb Shayale, and visitors left Kerestir both spiritually and physically sated.

As his last moments in This World slowly ticked away, Reb Shayale promised his heartbroken followers that those who came to his house would be helped just as they were when he was alive. In further discussion with his children, Reb Shayale explained that his promise of continued posthumous yeshuos was contingent on a single condition — that the chesed emanating from his house would continue after his passing just as it had in his lifetime.

His descendants are determined to carry on their zeide’s legacy. And judging by the crowds who flock to Rav Shayale’s house year round and especially on his yahrtzeit, where they’re welcomed with food, a bed, a mikveh, and anything else a visitor might need, they’ve been successful.

The yahrtzeit last week saw a record influx of 35,000 visitors to Kerestir, representing frum Jews from all across the spectrum, with men attired in hats of every kind, even Yankees caps, and visitors ranging from babies to the elderly.

It Takes a Village

As a countryside hamlet with a population of approximately 1,000, Kerestir isn’t exactly designed for large-scale events. The region is known primarily for winemaking, and large supermarkets are virtually nonexistent. Organizers had to invest considerable thought and effort, working closely with the locals, to keep the yahrtzeit event from overwhelming the area.

The entire event is done by the book and is coordinated closely with the local police chief and Kerestir mayor Istvan Rozgonyi, who described the annual commemoration as “surreal.” The annual influx of Jewish visitors has left some of the village’s residents dealing with culture shock, and Reb Mendel doesn’t hesitate to credit Reb Shayale’s influence for helping smooth the way with Kerestir officials.

Weeks and even months of planning go into each yahrtzeit, which is typically a three-day affair. The 98th yahrtzeit this year was managed by Yochanan Fleishman’s YF Productions, which handles large-scale events, trade shows, and other mass events, including the Ribnitzer Rebbe’s yahrtzeit in Monsey.

A pilgrimage of these proportions demands a well-oiled team effort. A staff of 75 people from YF Productions and Yossi Glick’s Next Level Events dealt with running the production side alone, with dozens of others on hand to manage the event’s individual components.

First responders from Ichud Hatzalah provided medical care, with only minor issues reported among the estimated 100 people who were treated, although several ambulances and a fire truck were on standby to deal with more significant concerns were they to arise.

Boro Park Shmira returned to Kerestir for the sixth year, with a team of 25 managing both traffic and facilitating crowd control, particularly at the tziyun, where long lines snaked their way through barricades to ensure that everyone had a chance to have a few precious seconds at Reb Shayale’s kever.

Twenty-four-hour security was provided by a team of 64 people, employees of a local security company, each of whom worked 12-hour shifts.

Visitors flying in for the yahrtzeit typically arrange flights through Budapest, located just over two hours away, although those arriving from Europe, Eretz Yisrael, or by private jet can avail themselves of the Debrecen and Kosice airports, situated about an hour’s drive from Kerestir. Traffic within the village itself is shut down for the yahrtzeit, with two large parking lots arranged on both sides of Kerestir to accommodate the influx of vehicles, which reportedly sparks the hottest rental car surge in Hungary each year.

More than 50 shuttles ferried passengers between the two lots to Reb Shayale’s house, which Rabbi Berish Rubin, Reb Mendel’s brother, describes as the “tachanah merkazit” of Kerestir. Visitors to Reb Shayale’s house can always get a bite to eat, a full meal, temporarily store their luggage, hail a taxi, print their boarding passes, find a place to catch a quick nap, take advantage of an on-site mikveh, or write up a kvittel to place at the tziyun in the dedicated “kvittel shtub,” which is stocked with 15,000 pens and 65,000 sheets of paper.

Finding one’s way around Kerestir isn’t complicated. Two hundred and fifty printed signs guide visitors, while display screens tap into tracking devices placed on the designated shuttles to let visitors know the expected wait time for the next van, and whether its destination is the parking lots or Reb Shayale’s tziyun up the hill. On the yahrtzeit, extra vehicles ran during peak hours to keep things moving.

In the tziyun itself, hundreds of barriers kept traffic flowing smoothly through the ohel, with tents brought in to expand its capacity, while open-sided tents for candle lighting and dozens of portable restrooms were brought up the hill to accommodate visitors.

“We have to bring everything up,” says Reb Mendel. “There is no sewer there, nothing. We even have to bring up water.”

The organizers put special emphasis on ensuring that visitors on both sides of the mechitzah feel comfortable, and pride themselves on arranging spacious accommodations for the many women who come, while a dedicated tent serves as the women’s eating area. An extra door was added this year at Reb Shayale’s tziyun to prevent the bottlenecks that occurred previously when dozens of women were coming and going simultaneously from the same entrance.

“Everything we had for the men, we had for the women,” notes Reb Berish. “We put in so much effort and do our best to accommodate them in a bekavodig way.”

Just two days after Reb Shayale’s yahrtzeit, Reb Mendel’s parents, Reb Shaya and Rebbetzin Rochel Malka, both in their early sixties, were still in Kerestir. Far from relaxing after another successful event, the Rubins were brainstorming potential improvements for 2024 to help women feel more connected to Reb Shayale at his tziyun.

Guarded from Afar

Reb Shayale passed away in 1925 at the age of 74, with his only son, Reb Avrumele, stepping in as his successor. Twenty short months later, Reb Avrumele passed away, and his son-in-law, Rabbi Meir Yosef Rubin, became the next rebbe of Kerestir, continuing Reb Yeshayale’s mission of providing for the poor and making himself available to anyone who sought his counsel or his brachos.

While Kerestir’s Jewish community only consisted of several hundred members, they weren’t spared the devastation of the Holocaust. Rav Meir Yosef was murdered in Auschwitz, leaving his son Rav Mendel Rubin as his successor. Returning to Kerestir after the war, Reb Mendel reestablished 68 Kossuth Utca as a destination for those in need.

“My grandfather got married there and had a child in that house,” recounts Reb Mendel of his namesake. “He would go to the train station to meet people who were coming back to Kerestir and take them back to his house and give them food. He tried with all his strength to make sure that people knew that the house was open again and that there was food for the refugees.”

Despite his best efforts, the senior Reb Mendel found it impossible to remain in postwar Kerestir. In 1948, he moved his family to America, while continuing to keep watch on his hometown from afar.

Reb Shayale’s house was taken over by the government, and a non-Jewish family moved into the home that had been a bastion of chesed for decades. Still, Reb Mendel continued sending money to Kerestir to ensure that the cemetery was maintained, and he kept in touch with some of the locals. When the opportunity presented itself to visit Kerestir, he eagerly made all the necessary arrangements to go with his children.

“It was complicated,” notes the younger Reb Mendel. “You had to arrange visas in a communist country, where they followed you around with huge guns. It was mamash impossible.”

The first glimmer of hope to reestablish a Jewish presence in Kerestir emerged in 1997 when Reb Shayale’s house was bought by the Rieder family. Their grandfather, Reb Shmuel Yosef Rieder, had been an incredibly devoted chassid of Reb Shayale, and they hoped to perpetuate his legacy in this way. Two years later, a chanukas habayis was held at Reb Shayale’s restored house, and slowly but surely, Jews began returning to Kerestir.

Open House

One hundred fifty people came to Kerestir to mark Reb Shayale’s yahrtzeit in 2004, a number that increased steadily with every passing year. By 2013 the crowd had swelled to 1,000, but it was just a harbinger of things to come.

The ohel covering Reb Shayale’s kever at that time was a replacement for the original structure that was destroyed during World War II. Built under the communist regime, it was large enough to accommodate just 10 to 20 visitors and nowhere near adequate for the many visitors who were coming to daven at Reb Shayale’s tziyun.

Reb Mendel’s parents, Reb Shaye and Rebbetzin Rochel Malka, took it upon themselves to expand the ohel into something that would be better suited to accommodate the large number of people arriving in Kerestir each year for the yahrtzeit. They built a new ohel on the structure’s original foundation that was large enough to squeeze in as many as 100 visitors.

The 2010 publication of Moifes Hador, a book written in Hebrew by Reb Mendel and Rabbi Shulem Eliezer Lichtenstein to tell the world about Reb Shayale and his legacy, was followed by a Yiddish translation titled Der Vinderlicher Tzaddik two years later. Both books were so well received that they inspired 2,000 visitors to come to Kerestir for Reb Shayale’s yahrtzeit the next year and were ultimately reprinted multiple times.

And after that, to borrow a term from today’s vernacular, Reb Shayale went viral.

By 2017, 10,000 people spent the third day of Iyar in Kerestir, partaking of the hospitality in Reb Shayale’s house and leaving mountains of kvittlach at his tziyun. A crowd of 25,000 commemorated Reb Shayale’s yahrtzeit in Kerestir in 2022 but even that impressive turnout paled by comparison next to last week’s yahrtzeit, which saw 35,000 people coming to honor Reb Shayale in his hometown.

Reb Berish notes that while people who have come to Reb Shayale’s tziyun have always seen personal yeshuos, miraculous things seem to be happening on a much larger scale since the ohel’s expansion.

“For 70 years Reb Shayale’s yahrtzeit was only known to family and his close followers,” observes Reb Mendel, who at 38 devotes himself full time to perpetuating his elter-elter-elter zeide’s legacy. “But in the last ten years it’s become something much larger.”

Reb Mendel offers his own explanation for Kerestir’s growing popularity. The publication of his book on Reb Shayale in multiple languages introduced 60,000-70,000 people to the tzaddik of Kerestir, with Feldheim’s English translation authored by Rabbi Yisroel Besser in 2017 under the simple title Reb Shayale now in its fifth printing.

“I’ve gotten feedback from thousands of people who finish reading the book and decide to pick themselves up and go to Kerestir,” says Reb Mendel. “No one ever told me that they felt inspired this way when they finished reading a book about another tzaddik, but when you finish this book you feel connected. You think to yourself that you have to go visit Reb Shayale’s kever and his house.”

The fact that Reb Shayale’s house is open year-round to welcome guests also adds to Kerestir’s magnetic pull.

“His house is an attraction,” explains Reb Mendel. “People come to daven in the place where he davened, to cry out in the place where people cried out to Reb Shayale, and to have coffee and cake in the place where people ate so many years ago.”

The new, larger ohel also holds a special appeal, particularly since it was built to Reb Shayale’s specifications.

“Reb Shayale had said that he wanted a window in his ohel so that he could look out on to the town and be mashpia on the people there and watch over them,” remarks Reb Mendel. “The one built 50 years ago didn’t have the windows in back facing the town, but this one does, and since it was built, things here just keep growing and growing and not stopping.”

A Covid Kerestir

With 17,000 visitors descending on Kerestir in 2019, organizers were already hard at work putting together the next yahrtzeit when Covid struck with a vengeance. People spent an unthinkable Pesach alone, and as hospitals struggled to cope with the influx of critically ill patients and the world found itself on lockdown, the idea of being able to travel to Kerestir for the yahrtzeit just days later became an impossible challenge. Wary of the pandemic and its devastating effects, Kerestir closed its doors to outsiders, putting the customary yahrtzeit visit to Reb Shayale in jeopardy.

“We decided to make something very special,” recalls Reb Mendel. “We made a campaign and advertised everywhere that people could send kvittlach to Reb Shayale for free. We set up a website, and close to 30,000 people responded. We had someone by the tziyun with a printer, and whatever kvittlach came, he put in.”

There was a minyan at Reb Shayale’s tziyun for his yahrtzeit, but just barely.

“My father got a special permit, and he was able to go,” says Reb Mendel. “There were maybe 16 people in Kerestir.”

Things were still difficult in 2021, even as the situation improved. Organizers needed a large number of permits for the yahrtzeit, which drew approximately 3,000 to 4,000 people.

“We weren’t allowed in the streets, we needed masks, and we had a ten p.m. curfew,” says Reb Mendel. “It was definitely a more difficult year for us.”

Since then, organizers have worked hard to build relationships with local officials, an effort that has resulted in tremendous cooperation and positive developments over the last two years.

Heavenly Hospitality

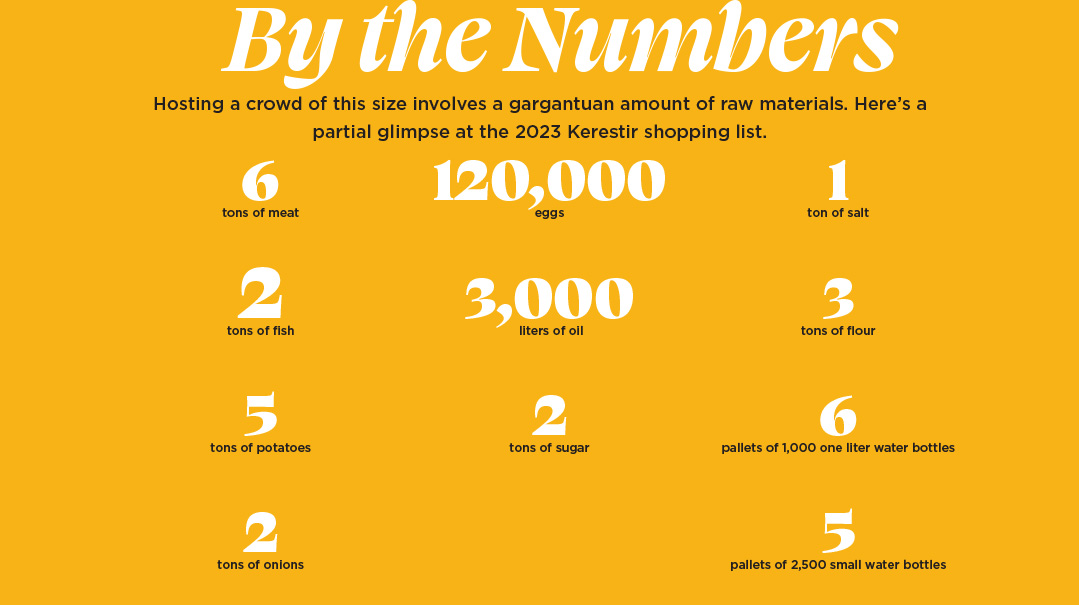

The logistics of feeding 35,000 visitors are staggering. Four full containers of food and dishes were sent to Kerestir in advance of the yahrtzeit to ensure that the team of ten chefs and 31 kitchen workers had everything they needed to create culinary magic. Meat items were prepared in the recently completed Kis Roszi Kitchen, located in a building donated by Shlomo and Esther Werdiger, in memory of Mrs. Werdiger's mother who was born in Kerestir, with a new milchic kitchen and bakery to be up and running within several weeks to accommodate future guests.

The amount of food served by waiters clad in black sweaters emblazoned with the “Reb Shayale’s hoiz” logo at three separate yahrtzeit seudahs, each of which were attended by over 2,000 guests, might seem mind-boggling, but Reb Mendel sees it as the natural continuation of Reb Shayale’s renowned hospitality.

“We had a meat kitchen, a milk kitchen, and a bakery,” reports Reb Mendel. “We brought in chefs from all over the world, with our main chef, Efraim Tambour of Belgium, running the kitchen in Reb Shayale’s house all year long. The feedback we got from people was amazing, with everyone commenting on how the food was really something special.”

This year’s program began on Shabbos, two full days before the yahrtzeit, with several hundred people in attendance, including many of Reb Shayale’s eineklach. Two sifrei Torah were dedicated in Kerestir this year, one by the Rieder family and another by Reb Yokel Gross of Miami, who at 93 years old is Reb Shayale’s oldest living grandchild. Special seudos were held to mark those joyous events.

“There was food being served on the yahrtzeit all night long, with fleishigs served in the tents in the front and milchigs in the back,” notes Reb Mendel. “In the morning, the fleishig [equipment] was taken away, and all the tents were used for milchigs, with people coming and going throughout the day.”

“I tell everyone: Even with all the chesed that is being done in the whole world, it’s still just a fraction of what goes on in Reb Shayale’s house,” adds Reb Berish.

Not surprisingly, it takes a significant budget to host 35,000 people. Reb Mendel lists the event’s price tag at $2 million, with another $3 million needed to run Reb Shayale’s house and tziyun for the remainder of the year. Some of the cost is funded by private donors, but donations are typically on the smaller side, leaving the Rubin family to raise the rest of the funds. Still, they keep looking forward, and despite the many costs involved in running the site as is, plans are underway to rebuild Reb Shayale’s shul and beis medrash on its original foundation, estimated at a $5 million project, as well as a $3.5 million mikveh that will be significantly larger than the current one in Kerestir.

Miracles, Past, Present, and Future

Even in his youth, it was clear that there was something special about the boy who would one day become Reb Shayale, with marketplace vendors recording exceptional sales whenever he walked by, and it would be an understatement to say that many, many pages could be written about the miracles that came about through Reb Shayale’s brachos. The stories recorded in Reb Mendel and Reb Shulem Eliezer’s book, which is in the process of being translated into both Portuguese and Hungarian, include dozens and dozens of tales that are clear examples of Divine intervention.

Reb Shayale’s reputation for being able to keep mice at bay began in Kerestir, and his image is still used to keep rodents away to this day, but his influence hardly stops there.

There was the story of the man whose gravely ill wife was cured after he agreed to Reb Shayale’s request that he began observing mitzvos, and gave her three cubes of sugar given to him by the tzaddik, one each after he davened Shacharis, Minchah, and Maariv.

There was the time when Reb Shayale was serving as the gabbai to the Liska Rebbe and told a man whose laboring wife was in distress to recite Yizkor, with a healthy baby born that same day. Asked by the Liska Rebbe to explain his advice, Reb Shayale replied simply, “When Yizkor is said, the children go out.”

Asked to share his favorite Reb Shayale story, Reb Mendel doesn’t hesitate even a moment.

“It was three years ago Erev Rosh Chodesh Elul during Covid,” says Reb Mendel. “My partner Reb Shulem Eliezer and I were in the kvittel shtub at five p.m. preparing to go to the tziyun, when he gets a phone call from his wife, telling him that his 14 year old son was being taken by helicopter to Westchester Medical Center because a tree had fallen on his leg in camp.”

Reb Mendel realized right away that something seemed off. While clearly an injury involving a fallen tree was a serious matter, that wouldn’t ordinarily indicate airlifting a child to a more equipped hospital.

“On our way up to the tziyun, Reb Shulem Eliezer called a Hatzolah coordinator, and he was told that his son had been hit in the head by the tree and that he was unconscious and not responding,” remembers Reb Mendel. “They were sure this was the end.”

Both Reb Mendel and Reb Shulem Eliezer were panic-stricken as they made their way up to the tziyun, particularly when they learned that weather conditions made landing in Westchester impossible, and the helicopter had been diverted to Albany.

“You have one parent in Brooklyn, another in Kerestir, and a boy landing in Albany in critical condition,” says Reb Mendel. “He is my closest friend, and we had spent hours together working on the Reb Shayale stories — all the research and all the writing.”

While Reb Shulem Eliezer was understandably frozen, Reb Mendel found himself emotionally charged. He walked into Reb Shayale’s tziyun and spent two hours there crying.

“I said to Reb Shayale, ‘This can’t happen. He’s next to you. He came to you. You can’t let this go — he came to you, and this is what happened?’ ” recalls Reb Mendel.

Reb Shulem Eliezer flew back to New York a day later, and three days later his son walked out of the hospital as if nothing had happened. Doctors told Reb Shulem Eliezer they hope his son understands that his recovery was something extraordinary.

“The doctors showed the parents the CT scans of when their son came in on Wednesday and told them it was impossible that his CT scan looked perfect just five days later, when he was released.”

“There are stories about Reb Shayale, a lot of them, every day,” says Reb Mendel. “What goes on at Reb Shayale’s tziyun is unbelievable.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 959)

Oops! We could not locate your form.