How to Blow Up Your Campaign

DeSantis is gambling on a strategy that only seems to work in politics

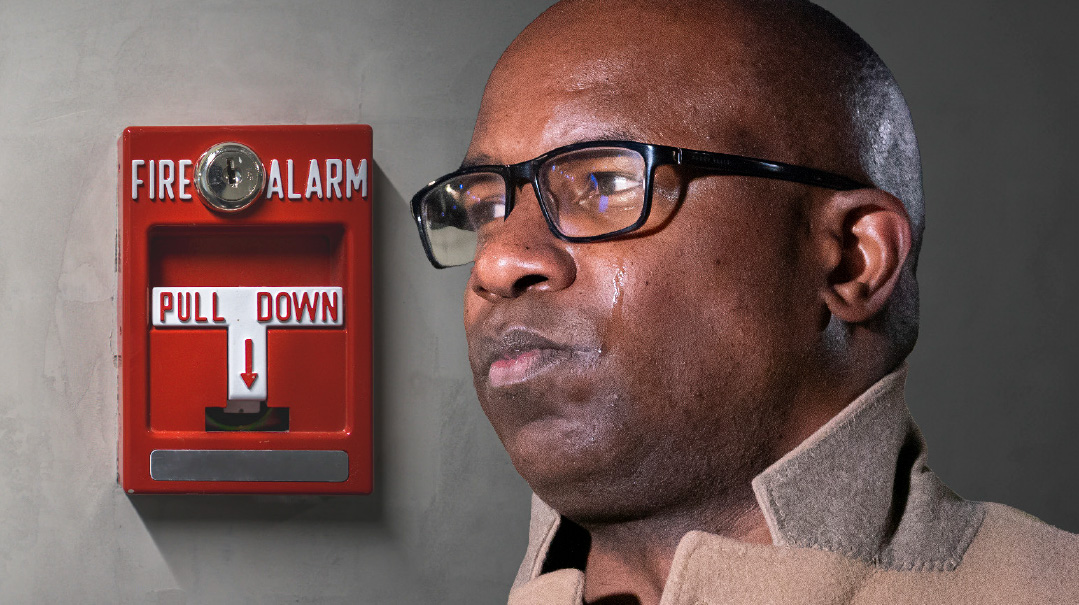

Photo: AP Images

Florida governor Ron DeSantis shook up his presidential campaign, firing his manager and cutting more than a third of the staff. Predictably, this is creating a climate of doubt around DeSantis and fomenting derision of the erstwhile front-runner’s odds of victory. On its face, the move should signal the end of his campaign.

Think of it this way. Would you invest in a company’s stock when the CEO is replaced and most of the employees are laid off? Would you panic if everyone you worked with was no longer there?

Despite this bad look, DeSantis is gambling on a strategy that only seems to work in politics: the art and science of blowing up one’s own campaign.

The Science

Campaign structures are made up of insiders and outsiders. Insiders include family members and close friends who have been with the candidate for decades, and of course large donors who are bankrolling the campaign. The insiders fancy themselves as scientists working to develop exactly the right formula to get their candidate elected. The outsiders are pollsters, fundraisers, door-knockers, and a host of other critical staff who try to make the insiders’ vision a reality. The insiders and the outsiders experiment with potions and chemicals, in the form of speeches, appearances, and interviews, and statements, to come up with the right mix.

Until, boom. Something goes wrong in the lab and the “perfect candidate” explodes. Poll numbers plummet, the media turns nastier, fundraising begins to dry up. The insiders panic and decide it’s time to remove the outsiders.

Senator John McCain famously did this in his 2008 presidential campaign when he fired his campaign manager and chief strategist before a primary. At the time, Oklahoma governor Frank Keating, a McCain insider, said, “I think it’s a smart thing. I think it’s a wise thing, and now I think it will make for a stronger campaign.”

Keating was right. McCain went on to win the primary. In 2004, Senator John Kerry fired his campaign manager, sparking a successful turnaround that won him the Democratic nomination. Kerry and McCain didn’t invent this strategy; it’s existed forever in politics. When John F. Kennedy was running for Senate in 1952, his campaign floundered quickly. There were too many cooks in the kitchen and no political organization. Younger brother Robert F. Kennedy (RFK), the ultimate insider and a political wunderkind at 26, took over and managed to revive the campaign and elect his brother.

Science boils down to observation, experimentation, and testing. When applied to a presidential campaign reset, it is about observing what’s not working, experimenting with a new structure, and testing the theory in the early states such as Iowa or New Hampshire. It follows a formula that can reinvent, rejuvenate, and refresh a stagnant campaign. But winning the campaign is an art.

The Art

It takes time, practice, and skill to become good at any art. This is why I still can’t paint, or play an instrument, or cook. In politics, the art of resetting a campaign is much harder, because the factors that one must account for are constantly changing: how adversaries are positioning their campaigns, the state of the economy, and the national mood.

A campaign reset is only a guesstimate within a particular political climate, which can change just like the actual weather. The “art” is navigating the retooled campaign through constantly changing elemental forces in an impossibly short time frame. Yes, you got sunburned and are now wearing sunscreen; but what good will that do you when it starts raining?

Trump’s two campaigns give contrasting examples of how difficult this art is.

In 2016, Trump fired campaign manager Corey Lewandowski with less than six months remaining before the election. This seemed like a desperate move, but press reports indicated that family member “insiders” wanted Lewandowski out. Trump revived his campaign and went on to win.

In 2020, with less than five months remaining before the election, Trump fired campaign manager Brad Parscale. Lightning didn’t strike twice; the weather had changed since 2016, and this time Trump lost.

The first time around, the reset benefited the campaign. His tactics and message resonated with an electorate that was seeking change and was uninspired by Hilary Clinton. The second time around, he was the incumbent, and the combination of Covid, the economy, and a well-run Biden campaign proved too much for his new campaign team.

Art and Science

A good reset necessitates not only an overhaul but also requires that the new team quickly master the changing political climate to the candidate’s benefit. This is easier said than done, and many campaigns fail at this duality.

Bottom line: DeSantis made the right move in resetting. His campaign was at a critical stage, and he couldn’t afford to continue to spiral downward.

That being said, he brought in a member of his gubernatorial team to head his campaign, a trusted insider who can help move him where he wants to go. But does this person have campaign experience? Can he artfully pivot as outside forces and issues mount?

Rather than just hoping this works, DeSantis would be wise to add seasoned campaign staffers to his new team. To mount an effective comeback, he needs to truly master the art of blowing up a campaign.

Front-Runner’s Dilemma

There is a cardinal rule in campaigns: If you are ahead, don’t do anything to bring attention to your opponents. This is Donald Trump’s dilemma as the GOP presidential debate edges nearer. By the time you read this, the debate will have taken place, and Trump will (likely) not have attended. Trump’s reasoning is sound; he has only to lose by giving the spotlight to those polling at an infinitesimal fraction of his Goliath lead. Why risk it?

A similar dilemma confronts the challengers. If you are on that debate stage, how can you not spend your time discussing Trump?

These twin dilemmas wrestle the attention back and forth between front-runner and challenger like a game of tug of war.

RFK is one of my favorite examples of this game. In 1964, RFK was running for Senate, and his opponent, incumbent Kenneth Keating, was trailing him. Keating asked for a debate, and RFK, realizing he had a lot to lose, declined. Keating went forward and debated an empty chair meant to represent his opponent. Not to be one-upped, RFK showed up at the studio where the debate was being filmed and banged on the door to be allowed in. Keating feared this challenge and fled out a back door, leading to devastating photos of his retreat and power being wrested back to the front-runner, RFK.

This GOP debate is just game one, with many more to be played. The front-runner and the challengers will be stuck with their dilemmas for some time yet.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 975)

Oops! We could not locate your form.