House of Cards

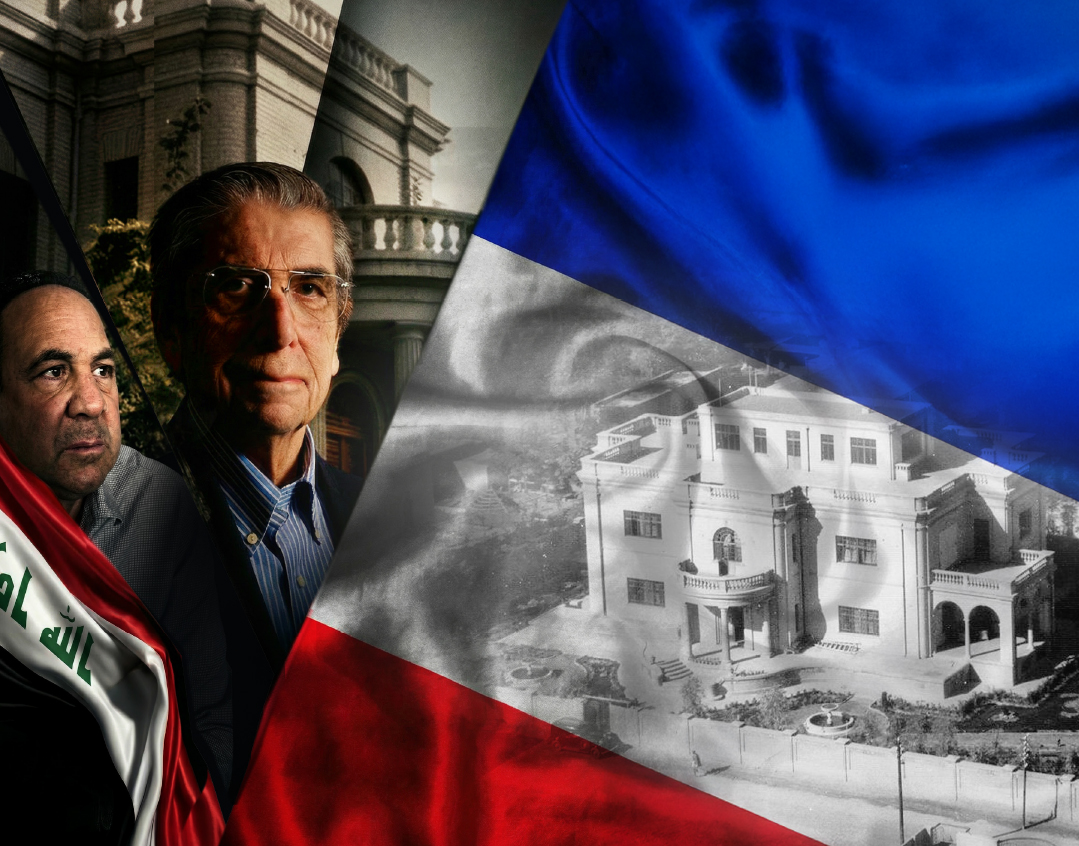

| February 17, 2026The French Embassy has been squatting in the Lawee family’s Baghdad mansion for decades. Can they reclaim it?

Photos: Family archives

The stately mansion on the banks of the Tigris in Baghdad is currently the French Embassy, a strategic outpost in the heart of the Mideast. But to the Lawee family, it’s stolen property, like the other plundered treasures of the Iraqi Jewish community. Yet the thief is a liberal European government, and the family has gone to court, intent on holding the French to their own professed standards

In the Land of Abaye and Rava

Rav and Shmuel, the Jewish experience in this world was formed, refined, and developed for the ages. Bavel, Babylon, Baghdad — they’re all names for the place in which the Jewish People sat and cried, but then dusted themselves off and flourished… only to be reduced to tears again and again.

Like our first arrival at its rivers and most of subsequent Jewish history, the eras of the Amoraim and Geonim involved repetitive cycles of persecution and relief. It’s a cycle that has perpetuated itself throughout our prolonged exile, and the 20th century was no different.

Tens of thousands of bnei Torah lived and learned in Iraq, the land that was once home to ancient Bavel. Luminaries, including Rav Abdallah Somech and the Ben Ish Chai, presided over dozens of batei knesset and yeshivot such as Shaf V’Yasiv and Midrash Beis Zilcha Talmud Torah. A powerful, successful kehillah thrived for centuries, until it was robbed and subjected to expulsion and confiscation of its assets.

The ongoing saga of the Lawee family and their ancestral home on the banks of the Tigris River, built in 1939 by brothers Ezra and Khedouri Lawee, is another chapter of this alternately triumphant and tragic pattern.

Phillip Khazzam, grandson of Ezra Lawee, who is leading the family’s campaign for justice from the French government, says the Beit Lawee battle is not only about one family and their home. It’s not even limited to the hundreds of thousands of Jews living in Arab countries who were stripped of their property in 1947, with no UN resolutions calling for their return. It’s a commentary and microcosm of the Jewish story through the exile, the uneven applications of social justice that narrate it, and the battered principles of right and wrong.

A Building in Shinar

The Tigris River flows through Baghdad today much as it has for over 5,000 years, a silent witness to the rise and fall of empires, the brutality of dictators, and the core elements of our mesorah. And the house has seen its own share of history in the 80 short years it’s stood beside the river.

The elegant mansion, nestled in the upscale Al-Mansour district, adorned with fountains and palms and cooled by the breeze blowing off the Tigris, was majestic enough to have hosted family chuppahs in its gardens. It was conceived as a home to generations of a family whose roots in the region predate modern borders by millennia.

Today, to the locals it’s the French Embassy. To the diplomats of Paris, it’s a strategic outpost in the heart of the Middle East. To the Lawees — like so many Middle Eastern Jews — it’s stolen property, symbolic of widespread generational treasures of the old Iraqi Jewish community, lost to mobs and squatters.

The difference between the Lawee house and so many others is the identity of the thief. While most were taken by unnamed, untraceable squatters, the Lawee home is occupied by a liberal European government, complete with human rights slogans, self-righteous criticism of others, and even a court system.

And now, the Lawees are intent on holding the French government to its own self-professed standard.

Birthplace of the Bavli

From Churban Bayis Rishon, right up through the late stages of the Ottoman Empire, Jews in Iraq lived the places, rivers, and roads of the Talmud Bavli. In the 1800s, over 10,000 bnei Torah attended at least 28 shuls, and learned from great Sephardic poskim and luminaries. Religious and communal life was a strong reality until the upheavals of the 20th century.

Ottoman reform, British imperial politics, Zionism, and the rise of Arab nationalism slowly recast Jewish life. Under the British presence in the early 20th century, Iraqi Jews still held influential roles in commerce, law, and government service; many of Baghdad’s leading merchants and professionals were Jewish and deeply integrated into urban life. The Jewish community had between four and six representatives in the Parliament and one member in the Senate. By 1940, over 135,000 Jews lived in Iraq, with 90,000 in Baghdad (between 25% and 33% of the city’s population).

Brothers Ezra and Khedouri Lawee were two such Jews. “My father held the concessions for General Motors in Iraq,” says Mayer Lawee, the 87-year-old son of Ezra Lawee. “He held the franchise rights for Chevrolet and Pontiac in Iraq, Iran, and Israel. He was a major entrepreneur.”

The Lawees didn’t just sell cars and trucks; they helped build the modernization of infrastructure. Vehicles were key to the development of emerging countries like Iraq, and the Lawees sold more than transportation; they sold status. During World War II, when the family moved temporarily to India, Ezra continued to import cars and trucks for the British Army fighting in World War II, handling business for General Motors across the Middle East.

“Everyone within the Iraqi community had such high respect for him and he for them,” remembers Roberta Lawee, his daughter-in-law. “In those times there weren’t really differences of Jew versus Arab. They were all working together. Mayer’s uncle (on his mother’s side) was an officer in British intelligence. My father-in-law was close with King Faisal II of Iraq — in fact, when the pogroms began, he [the king] was the one who tipped him off to the danger and encouraged him to seek safety.”

Trouble in the North

The peaceful coexistence cracked during and after World War II. The Farhud pogrom of June 1941 — an outbreak of mob violence in Baghdad — was a traumatic turning point that signaled to many Jews that their position could no longer be taken for granted. With Erwin Rommel camped at the gates of Egypt, Nazi-inspired rioters attacked Jews on Shavuos, killing 180, injuring 600, and looting 1,500 stores before Iraqi troops restored order. This was the tipping point.

The partition of the British Mandate for Palestine and creation of the State of Israel in 1947 accelerated the breakdown. Between 1949 and 1951, tens of thousands of Jews left Iraq in what became known as Operation Ezra and Nehemiah. Most went to Israel, while many others dispersed to Europe, the Americas, and elsewhere. Their departure wasn’t simple; the Iraqis enacted laws that permitted emigration only on harsh terms. The departing Jews had to forfeit their citizenship and had their assets frozen or nationalized, often with little to no compensation.

Over ensuing decades, further discriminatory measures — including travel restrictions, summary arrests on fabricated charges of spying, and legal disabilities — reduced a once-thriving community to a handful. By the early 21st century, only a few Jews remained in the country that had once been a center of Jewish life.

“I don’t remember much from Baghdad… I was only a small child when we left, at the end of World War II,” Mayer Lawee says. The family moved to India, but later returned to Baghdad until the outbreak of hostilities in 1947. “My father told me the king called him and said, ‘Ezra, it’s time to go.’ ”

For families like the Lawees — who had roots in the country stretching back centuries — this violent unmooring meant not only a loss of place but the loss of the very rights and records that anchor inheritance and memory. Estates became vulnerable to seizure; houses, businesses, and bank accounts were frozen or handed to the state.

“They had such an incredible life, they felt so much a part of the community,” Roberta says, “and suddenly it was all taken away from them.”

The Lawees’ house would become a case study in how these legal and political transformations left heirs with a claim but little practical redress, facing a wall of two-faced political claptrap about human rights concealing a much darker record.

The family spent time in Israel and Egypt before moving to New York for a few years, and then eventually settling in Montreal, where Mayer met Roberta, an Ashkenazi Jewish girl from Winnipeg. She describes her impressions of Ezra Lawee, her father-in-law: “He was a real gentleman… When he moved to Canada, he tried to continue selling cars from General Motors. But the locals told him, ‘Mr. Lawee, you are way too much of a gentleman to sell cars in North America.’ That’s the kind of person he was.”

The Low Road

The Lawees would never be welcome back in Iraq again. But although they were thousands of miles away, they never truly left Beit Lawee behind. Ezra and Khedouri maintained ownership of the Baghdad mansion, leaving a cousin and Ezra’s sister-in-law Claire as caretakers to look after the property until she left in 1958. In 1964, knowing the French government was looking for a place for its embassy, Ezra identified an opportunity. Believing that a powerful foreign tenant would provide the best security for the estate, the family signed a lease with the French government.

For five years, the arrangement worked. France set up its embassy, and the rent checks arrived at the Lawee home in Montreal. But in 1969, the specter of the Ba’athist party — and the rise of Saddam Hussein — changed everything. “It had started in 1947,” Roberta says. “A number of family members stayed into the ’50s. But when Saddam Hussein came in, it was very, very difficult. They all had to escape.”

The Hussein government passed laws intended to freeze the assets of Jews who had fled, declaring that the property belonged to the state. It ordered France to stop paying rent to the Lawees and instead to pay the Iraqi Ministry of Finance.

France, a nation that prides itself on “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité” faced what should have been an easy choice. It could have stood by its contractual and moral obligations to the rightful owners. Instead, it chose money over morality, riches over rights, profit over payment.

“Saddam Hussein told France, ‘Don’t pay the family, pay us,’ ” Philip Khazzam explains. “France continued paying us for two years and then they just stopped.” From 1974 onward, France paid rent only to the Iraqi government — but only a tiny percentage of it. “They paid one-tenth, ten percent, of the market rent,” Philip says. “They saved ninety percent. The real reason they didn’t help us… is because they were saving big money on the rent.”

The French government does not dispute the basic facts: The home belongs to the Lawees, they signed a lease, and have not paid rent for nearly 55 years. The back rent requested by the Lawees is approximately $22 million, with some other estimates reaching up to $33 million, depending on what components (back rent, interest, moral damages) are counted.

Avoiding Accountability

The family made several attempts over the ensuing decades to achieve justice. A cousin of Phillip’s went to the Quai d’Orsay — the French foreign ministry — and tried to talk to them, but gained no traction. The property was “frozen,” and France used the legal limbo as a shield to avoid accountability.

In 2003, when the United States invaded Iraq and deposed Saddam, another opportunity presented itself. The family got a lawyer and former Quebec premier to write a letter to the Quai d’Orsay, again with no results.

“In 2011 and 2012, I was just doing research on it, calling contacts in Baghdad to try to get an idea of the value of the buildings there,” Phillip says. The current big push kicked off in 2020. “I realized that it’s not just property, it’s really a human-rights issue,” he adds. He retained high-powered lawyer Jean-Pierre Mignard, who was also the private lawyer of the French Foreign Minister.

The legal team tried diplomatic approaches with the French Foreign Ministry for several years, but the office changed occupants frequently and Khazzam got the clear sense that they weren’t serious about looking for a solution. Two years ago, his lawyer filed suit in the Paris Administrative Tribunal, arguing that France violated international law by complying with discriminatory, antisemitic legislation and illegally enriched itself with stolen real estate. The family’s legal team likened the case to the restitution of Jewish property stolen during the Holocaust. It argues that France, which claims to uphold equality and justice internationally, must reckon with benefiting from state actions that dispossessed a persecuted minority.

The French didn’t respond to the suit for nearly two years, until major Canadian newspaper The Globe and Mail featured it. “That really shook things up,” Phillip laughs. “We got a response within forty-eight hours.”

The French defense was basically to say: “We paid the Iraqis, go take it up with them.” They argue that the dispute is a matter for Iraqi courts, not French ones, and that they were merely following the laws of the country in which the property is located.

In February 2026, the court handed down a ruling that essentially agreed with all the claims of the French government, dismissing the case for lack of jurisdiction.

Shoddy Defense

Asked about the idea of turning to the Iraqi government, Khazzam doesn’t mince words. “That idea is preposterous, ridiculous,” Khazzam says. “I’m going to get a fair hearing in Iraq, the country that took the property away from my family? That’s not happening.” The family had tried to retain an Iraqi lawyer earlier in the proceedings to bring claims, but none would take the case.

The family has a very practical retort to the innocent French puppy-dog-face “what were we-supposed to do” claim. “Why didn’t they just simply continue to pay us and deduct the ten percent they had to pay the Iraqis?” Phillip asks. Saddam was only charging the French about ten percent of the rent. The French cannot now claim that they paid rent and the family needs to chase the Iraqis, because they didn’t. “If the French would have paid us the ninety percent they weren’t paying the Iraqis, we would be fine with that. But they chose to keep the money they owed us to enrich themselves unjustly.”

The family also points out that the Iraqi legal acts that froze Jewish property were themselves discriminatory and part of a campaign that targeted Jews specifically, giving rise to a moral and legal argument that a third-party state (France) claiming a moral high ground should not be allowed to profit from the fruits of a discriminatory regime. International human-rights law contains doctrines on persecution, and national courts have applied equitable doctrines of unjust enrichment when one party has received a windfall that would be unjust to retain.

Next Steps

Phillip has nothing but confidence for the way forward. “We’re just getting started,” he says, outlining a strategy that will take the appeal to the French Court of Appeals, then the Conseil d’État (France’s highest administrative court), and eventually the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. “But I don’t think it’s going to go that far,” he adds. “By the time it gets to the European court, if it does, it will have generated so much negative press for the French that they’re probably going to be very willing to just finish it, which is something they should have done already.”

After forcing France to pay back rent, the family doesn’t intend to renew the lease. “When France has to pay for back rent… we’re going to stop the renewal of the lease and we’re not going to lease it. We want to sell it,” Phillip said. “I think that it would be difficult for France politically to continue to rent the house after they’re forced to pay back rent.”

There are no other properties in the area that are even close to suitable for the French government to house their embassy. Real estate values climb at a rate of ten to 15 percent per year, and other embassies in the area have had their rent increased by 300 to 400 percent. With a cultural center nearby, and the French appetite for a nice building, it must stay in the area.

“Either they will buy the building from us, or another Middle Eastern country will be happy to buy it and rent it to the French,” Phillip explains. Either way, the house will be sold.

Dual Standard

A victory in the case could uncork a flood of claims against Middle Eastern countries, including Iraq itself.

The Lawee case is the canary in the coal mine for hundreds of thousands of Jews who were expelled from Arab lands in the 20th century. If France — a Western democracy — can legally justify occupying a Jewish home based on the laws of a “failed state” and a dead dictator, the precedent for restitution across the Middle East is bleak.

Phillip expressed a painful truth about the broader Middle Eastern Jewish experience: “No Jew has ever gotten anything from the Middle East,” he said, referring to the hundreds of thousands forced to leave their homes in 1947. Even today, dozens of Jewish-owned properties are frozen by the Iraqi government, maintained and rented for the purpose of preservation.

Most Middle Eastern governments are too rogue to be held accountable. The difference here is that claims can be brought against a bridge — the French, who were contractually responsible for the property for 55 years. Phillip argues that a victory would be a precedent for other families and could unlock frozen assets.

A victory for the Lawee family would have consequences beyond a single ledger. It would be a rare judicial acknowledgment that a modern democratic state cannot perpetually occupy property that was taken from a persecuted minority without bearing responsibility for the consequences of that occupation. It could provide leverage to other heirs of those who fled Iraq and left behind property that was frozen or nationalized in discriminatory contexts.

Justice is not about money, but the restoration of voice, record, and dignity. In this context, the Lawees’ case deserves careful tracking. For one family of many exiled and torn from their own home, restitution would be the Sephardic version of the Claims Conference, and an admission of the wrongs visited on the Jews of the Middle East.

Perhaps it can even tip the Palestinian refugee/fugitive narrative pushed by liberal European governments — like the French — against Israel. Instead of bombastic recognitions of a Palestinian state that has never existed, could dual-standard bearers like France’s Emmanuel Macron be forced to recognize their own complicity in robbing the very people they accuse of thievery?

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1100)

Oops! We could not locate your form.