Hope for Tomorrow

Veteran producer Dovid Nachman Golding hosts a walk down musical memory lane

One of the highlights of the Yamim Noraim is that feeling, whatever minyan or shul we go to, of being embraced in the davening by our favorite baalei tefillah. Some people enjoy chazzanus, while others prefer classic niggunim from the past. Most of us, though, have a certain individual or kehillah whom we entrust with our Yom Tov davening, in keeping with their special nusach or style of tefillah.

There’s a famous Biblical story at the end of Malachim I about a man named Navos, a righteous Jew who owned a vineyard next to the wicked King Achav’s palace. The king wanted that piece of property and even offered to pay for it, but Navos refused the offer — it was his ancestral territorial inheritance. Yet when Izevel, Achav’s contemptible wife, saw how distraught her husband was over the non-sale, she told him not to worry, that she’d arrange everything in his favor. And, in her own inimitable evil way, she did. She organized a corrupt tribunal, had Navos dragged into the court, and had him falsely convicted of blaspheming Hashem and the king, punishable by death. He was taken out and stoned, Izevel told Achav everything was now in order, and Achav, hearing Navos was dead (and not asking too many questions), went and claimed his property (causing Eliyahu Hanavi afterward to invoke the famous passage, “haratzachta vegam yarashta — have you murdered and also inherited?”). Both Achav and his wife perished by Hashem’s decree soon after, but the commentaries deal with a fundamental question: Why did Navos, a good man, have to pay with his life?

The midrash explains that Hashem endowed Navos with the most beautiful singing voice of his entire generation. Three times a year, when Am Yisrael were oleh regel to Yerushalayim, Navos would daven on the Har Habayis, and all the nation enjoyed the beauty of his voice. However, his talent got the better of him and made him haughty, and the next time he went to Yerushalayim, he refused to sing until the Jews begged and pleaded with him. One year, he didn’t join the nation at all, refusing to share his G-d-given talents with them. In the worst case, he was punished because he abused those talents instead of sanctifying them, and at the least, he didn’t merit Divine assistance in protecting himself from the evil plot against him.

Sincere baalei tefillah don’t ignore or trivialize Hashem’s generous gifts, and as part of the Jewish music industry, I see this constantly as well — artists using their talents to the fullest extent, stretching themselves to make other Yidden happy. Not a summer goes by that almost every Jewish performer ends up in Camp Simcha, Camp Hasc, the Ohel camps, and the many others out there for the special needs campers.

Just ask Shimshi Haskal from Mekimi if he ever hears the word “no” when he asks a performer to sing for cholei Yisrael. Likewise, for Mesameach in Lakewood and for the many similar organizations across the globe.

Shlomie Haskal, Shimshi’s brother, told me how MBD once went to visit a child in Hackensack Hospital. When the singing was over, the attending physician told Mordche, “You don’t know what you just accomplished.” MBD responded, “What do you mean I don’t know, I see the smiles.” The doctor replied, “You see his smiles, I see the vitals.”

A doctor once told me that there was a young patient who was on oxygen when Avraham Fried came to visit, yet by the time Avremel finished singing, the boy’s oxygen level had jumped high enough for the oxygen to be removed.

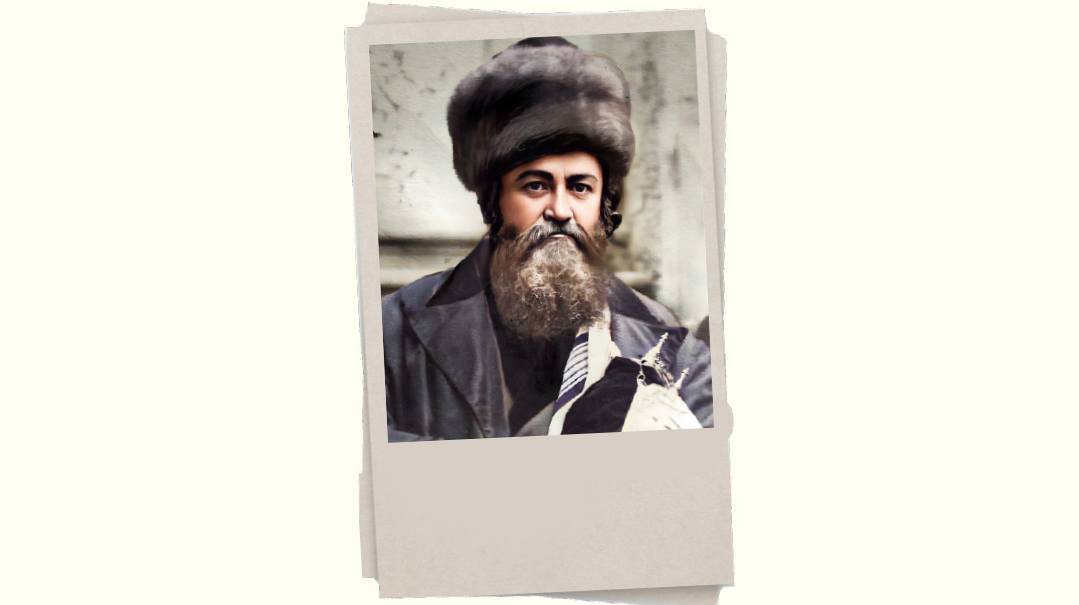

A friend of mine from the West Side, Leslie (Elazar Meir) Westreich, told me about his grandfather, the Kanczuga Rav in Poland in the 1930s. He had a truly remarkable voice and he was blessed with six sons, each of whom also had outstanding voices. One Yom Kippur night, after finishing Kol Nidrei and starting Maariv, the tzibbur looked out the window and saw many Polish locals loitering around the shul, some on horses, others in carriages. The crowd inside was frightened and expected the worst. The Kanczuga Rav himself went out to them, to see what they wanted and to see how they could be appeased. Much to his shock, the leaders of the Poles who had surrounded the shul replied, “We’re not here for trouble. We know that tonight the chief rabbi and his sons would be singing and we just wanted to hear the great rabbi and his children sing their beautiful prayers.”

Benny Friedman was davening in a California shul one Yom Kippur night, when an old man in the front row fainted. They quickly called 911, the medics arrived, and the patient regained consciousness and stayed in shul. One of the medics, an unaffiliated Jewish fellow who had just finished his shift, decided to stay in shul for the rest of the davening. He told Benny afterward that he believed this was G-d’s way of getting him to go to shul.

Every year before Rosh Hashanah, I listen to MBD’s vintage “The Bird of Hope.” This song, from the V’chol Maaminim album that Suki and I produced for him back in 1978, was written and composed by Dina Storch. It conveys the message of how a baal tefillah can pull us up from the deepest pit of despair to rise higher and even higher in our connection to HaKadosh Baruch Hu. Between Suki’s arrangements and Mordche’s vocals, the song always touches my soul. This Rosh Hashanah, as we all daven for the Geulah more intensely than ever, let us remember the very special words of that song: “Yes, I know there is hope for tomorrow; even though we fall, we will go high.”

Kesivah v’chasimah tovah.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1031)

Oops! We could not locate your form.