Honor the Journey

| October 15, 2025Sometimes, the most significant movement… is the one away from where we were

About 20 years ago, my friend Mayer and his two teenage sons, Eli and Yossi, went together to watch the 11th Siyum HaShas from a satellite location in Baltimore, where they lived. Like so many others there, they were swept up by the power of the moment: the unity, the music, the joy of Torah.

But what really stuck with them was a speech by Dayan Aharon Dovid Dunner from London. He related that all the bar mitzvah boys in his shul in England had taken upon themselves not to talk with their tefillin on. His words were electrifying. When the speech ended, Mayer and his boys looked at each other, almost breathless.

“We have to do something, too,” Mayer said.

“We’ll stop speaking devarim beteilim, (idle talk) while wearing tefillin, just like those English kids,” his son enthusiastically agreed.

Mayer paused, proud of his sons. “Let’s do it,” he said.

All three of them made a personal kabbalah not to speak while wearing tefillin. But they didn’t keep it to themselves. Mayer began encouraging others to join them, even giving cash prizes to kids who took on the commitment, quietly starting a local grassroots movement. He would go on to give these generous awards to over 50 neighborhood kids.

Mayer wasn’t the only one to have been inspired at the siyum. A friend of his, who had also attended the event, was similarly moved. When he heard about Mayer’s kabbalah, he decided to adopt it as well, but go a step farther. “I’m going all the way,” he said. “I’m buying a new pair of tefillin so they’ll be completely ‘clean,’ never worn while I was speaking idle speech. I’ll donate my old pair to someone else.”

Mayer smiled and said, “That’s wonderful.” But he had no intention of doing the same. I’m sticking with mine, he thought. These are the tefillin I’ve worn every day since my bar mitzvah. I’m not discarding them.

Years later, Mayer decided to get his tefillin checked. While typically the process takes a few days and people borrow another set until their own is ready, Mayer didn’t want to miss even a day wearing his own. So he waited until he was in Brooklyn for a visit, where he found a sofer who would check them the same day.

When he came back that afternoon to pick them up, the sofer looked at him and said, “Hey… can I talk to you for a minute?”

Mayer froze.

That’s not what you want to hear when you’ve handed over your tefillin for checking.

Uh-oh. What’s wrong? He thought. Are they pasul? How long have I been wearing them like that? How expensive will it be to fix them?

The sofer gently picked the tefillin up and said, “Where did you get these?”

“I’ve had them since my bar mitzvah,” Mayer responded.” My brother got them for me in Bnei Brak — he was learning in Ponevezh at the time.”

The sofer nodded slowly, almost reverently. “These are one of the nicest sets of parshiyos I’ve ever seen.”

“Really?” Mayer said, surprised.

“Do you know who wrote them?” the sofer asked.

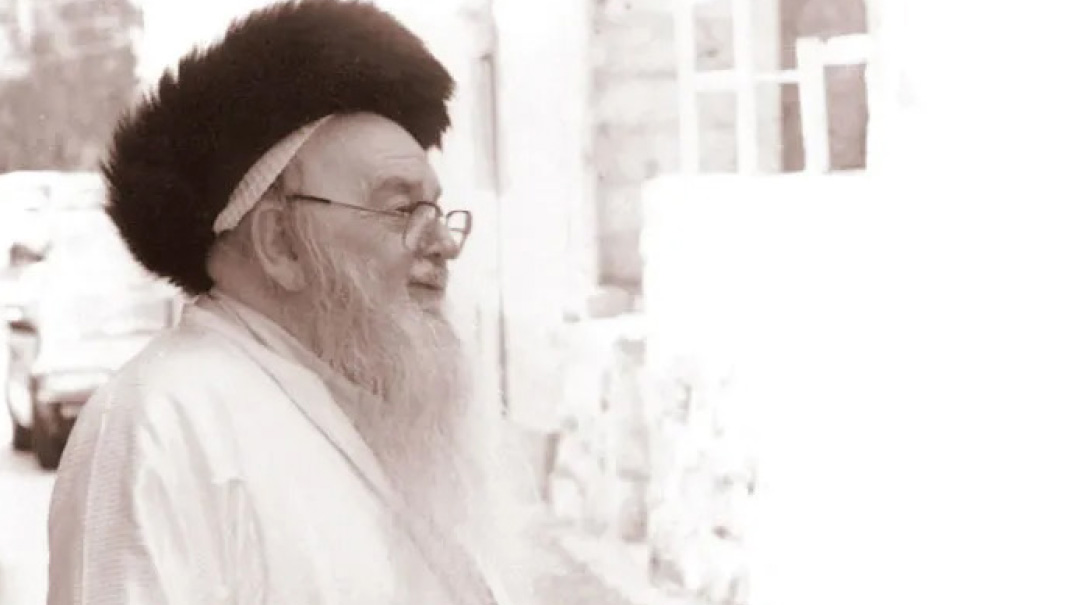

Mayer smiled. “Yes. Rav Chaim Friedlander ztz”l. He was close with my brother and did him a personal favor.”

The sofer’s eyes widened. “Rav Chaim Friedlander — the mashgiach of Ponevezh? Talmid of Rav Dessler? He wrote these?”

Mayer nodded. “That’s right.”

“These are a treasure,” the sofer said. “The ksav, the klaf — everything is just stunning.”

“You should know,” Mayer added, “I’ve always been very careful with them. I never leave them in a car, or in shul overnight, or anywhere exposed to heat or moisture.”

The sofer nodded approvingly. “In that case,” he said, “you really don’t need to check them again. They’re so beautifully written, and you’ve cared for them so well… you’re good.”

When Mayer shared this story with me, he said, “I could have donated my old tefillin and started fresh, like that other guy. But I didn’t want to leave behind my origin story. And as it turns out, that original step, my bar mitzvah tefillin, was more precious than I ever realized.”

It reminded me of something powerful we learn from the Taz, (Rav Dovid ben Shmuel Halevi, from 17th century Poland).

The Torah discusses the journeys of Bnei Yisrael from the time they left Ramses, Egypt, until they arrived at the edge of Eretz Yisrael 40 years later. While the Torah doesn’t say how many stations there were, Rashi tells us there were 42.

But if you actually count the stops, you’ll only get 41.

The Taz explains that Rashi is counting the point of departure, Ramses, as one of the 42 journeys.

There’s a deep life message here, I thought.

In our own journeys, we often focus only on where we’re going. What’s the next step, the next goal, the next destination?

But sometimes, the most significant movement… is the one away from where we were.

We each come from a “Mitzrayim.” It might have been a good place, or it might have been painful. But that point of origin — that story we carry — is part of the journey, too. It shapes us. And honoring that origin gives us strength.

When I shared this thought with Mayer, he gave me a fist bump and said, “I love that. That’s why I kept my tefillin. They’re a part of me. I want to continue building on my origins, and not discard them as I grow.”

Sometimes the greatest holiness doesn’t come from starting over; it comes from staying true to the path you’ve already begun.

Shlomo Horwitz is the author of Snapshots of the Divine (Adir Press/Feldheim 2024) and the founding director of Jewish Crossroads, an educational theater project providing creative Torah programming.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1082)

Oops! We could not locate your form.