Holy Dirt

| November 26, 2024One of the most highly prized commodities from Eretz Yisrael for millennia was dirt from Eretz Yisrael

Title: Holy Dirt

Location: Jerusalem

Document: Brooklyn Times Union

Time: 1904This is the first rule. Make it well known among them that no one has any permission to export dirt of Eretz Yisrael under any circumstances, on behalf of any community or individual, in any country under our jurisdiction, unless they obtain express permission from us to do so. Anyone who fails to comply with this measure and is caught exporting dirt of Eretz Yisrael without our permission will be sanctioned by us and not receive a single prutah of chalukah funds from us.

It is your responsibility to adhere strictly to this regulation, as well as to enforce it by ensuring that no member of your community violates this measure. You must warn everyone of the consequences that will be sustained for engaging in this practice. And you must duly inform us of the names of anyone who henceforth engages in this activity in order for us to implement the punitive measures against that individual as enumerated above.

—The Organization of Pekidim and Amarkalim on behalf of Eretz Hakodesh in Amsterdam, in a letter dated 6 Iyar 1852 to the administrators of Kollel Hod (Holland and Deutschland) in Jerusalem.

Fundraising to support Torah scholars in the Old Yishuv differed both from the time-honored ideal of that cause and from ordinary philanthropic support for the poor. Because the recipients were both talmidei chachamim and poor, financial assistance to the Old Yishuv wasn’t understood by the providers as being limited to the realm of philanthropy. It was rather understood as an act of reciprocity. Members of the Old Yishuv were provided with material needs by the Jewish communities of the Diaspora, while the holy scholars provided spiritual goods in return.

The members of Old Yishuv society saw themselves, and were in turn viewed by others, as an avant-garde representing the Jewish People in the Holy Land. By not engaging in material pursuits and instead focusing exclusively on Torah and avodah in Eretz Yisrael; praying on behalf of the klal at holy sites and graves of tzaddikim; performing the mitzvos exclusive to Eretz Yisrael; being sheltered from the social changes sweeping through 19th-century Diaspora Jewish life, and thus serving as a last enclave of holiness unaffected by modernity and its challenges, these beneficiaries facilitated a relationship between giver and receiver that constituted a functional transaction of goods, rather than purely an act of tzedakah for the needy.

The problem with this economic model was that while the giver provided material goods that were quantifiable and tangible, the spiritual goods they received in return were more abstract. As a result, the shadarim (Old Yishuv fundraisers) ran the risk of appearing as generic schnorrers, rather than representing a spiritual elite and partaking in a two-way transaction.

To overcome this challenge, the Old Yishuv developed a souvenir industry in the 19th century that supplemented the spiritual goods with symbolic relics that expressed the transaction in a more tangible fashion. Certificates of recognition for donors, all sorts of Judaica artifacts, artwork from Eretz Yisrael, and a host of other souvenirs were given to donors around the world. Obtaining relics from the Holy Land was a common practice among Christian pilgrims and communities for centuries, and it likely influenced the Jewish community in the 19th century. An entire industry developed around these items, and aside from presenting gifts to donors, entrepreneurs initiated a growing trade in the export and sale of Holy Land souvenirs across the Diaspora.

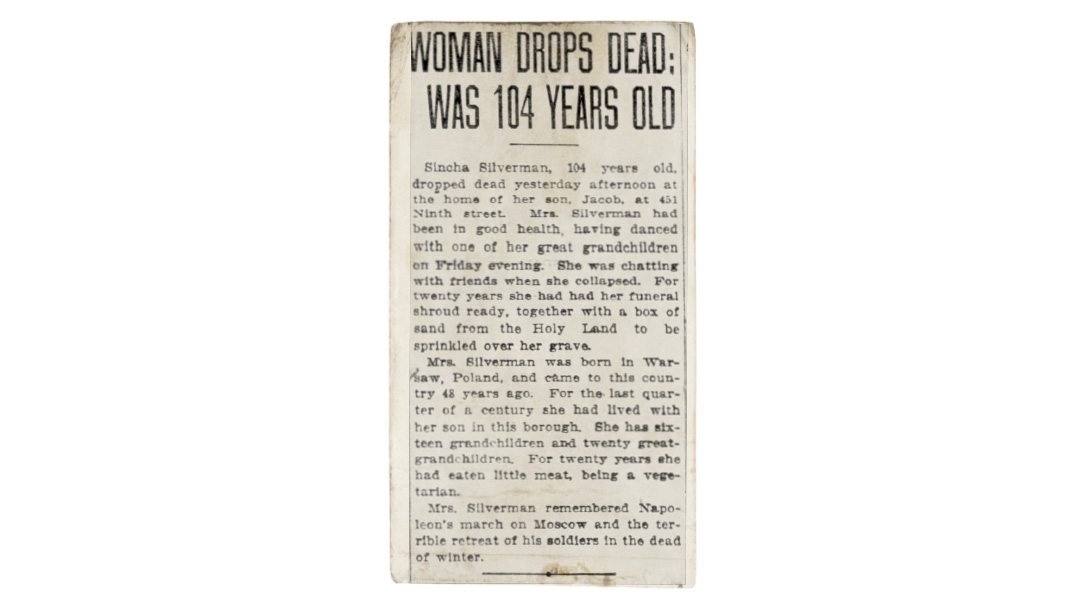

One of the most highly prized commodities from Eretz Yisrael for millennia — but which rose in prominence in the 19th century — was dirt from Eretz Yisrael. This soil was desired for burial in chutz l’Aretz. For many centuries, a handful or more of dirt from Eretz Yisrael was thrown in the grave during burial. In the 19th century, it emerged as a common gift for donors to the Old Yishuv, who then utilized it for their own burial or for their loved ones. The Eretz Yisrael dirt industry became quite commercialized over the 19th century. Generally, local communal chevra kaddishas would order large quantities of dirt through the fundraising apparatus of the Old Yishuv. Individuals in each community would in turn purchase the dirt from the chevra kaddisha for burials.

Sometimes the dirt wasn’t used for burial. Sir Moses and Lady Judith Montefiore built a shul at their Ramsgate estate, and at the cornerstone laying ceremony, the couple spread dirt from Eretz Yisrael in the spot where the aron kodesh was to be dedicated. There is evidence of other shuls engaging in this practice, and there were even instances where stones were imported from Jerusalem to serve as the cornerstone for a shul in Europe.

The powerful organization of the Pekidim and Amarkalim on behalf of Eretz Hakodesh in Amsterdam, with the legendary Rav Tzvi Hirsh Lehren at its helm, had for decades maintained a strict monopoly on the Eretz Yisrael dirt trade. They demanded that they be the sole importers and proprietors, set the prices, and oversee the distribution of the profits. Rav Tzvi Hirsh Lehren even related that he’d personally check the valises of his shadarim who arrived from Eretz Yisrael to Amsterdam, in order to ensure that they weren’t smuggling any dirt without his organization’s knowledge.

In 1853, another Amsterdam native named Rav Yehuda Leib Schaap successfully broke the monopoly heretofore the exclusive domain of the Pekidim and Amarkalim organization. As an aspect of his ongoing dispute with the organization, he imported several crates of Eretz Yisrael dirt, sold them wholesale at a fraction of the cost, and essentially broke the market. Thus commenced a significant wholesale trade war over Eretz Yisrael dirt at competitive prices.

The Vaad of the Pekidim and Amarkalim in Amsterdam viewed this development as not only a loss of revenue for their organization, but also as commercialization of a holy product, which was now being marketed as a cheap commodity.

In a letter to the Sephardic kollel in Tzfas in 1854, it was noted, “The love of the Land of Israel is lessened by the day. When everyone recognizes that dirt from the Holy Land is cheap, and that it’s traded just as any other product on the market, it loses value in their eyes. The kavod for Eretz Yisrael is lost as a result.”

Celebrity Dirt

A year prior to his passing in 1854 in New Orleans, a non-Jewish acquaintance of Judah Touro brought dirt from the Holy Land, which Touro requested that he be buried with. When Sir Moses Montefiore buried his wife Lady Judith at their Ramsgate estate, the coffin was covered with dirt from Eretz Yisrael, which had been imported expressly for this purpose, as it was lowered into the ground. To complete the connection his wife had with the Land of Israel, he had a mausoleum constructed over her grave that resembled Kever Rachel.

Holy Snuff

The dirt and stone industry was a concretization of the pasuk in Tehillim often used in fundraising drives for the Old Yishuv: “Ki ratzu avadecha es avaneha v’es afarah yechonenu — For Your servants have desired her stones, and her dust has found favor with them.” In a letter of appreciation for his activities on behalf of the kollel from Rav Yaakov Leib Levi of Kollel Warsaw in Yerushalayim, to Rav Eliyahu Guttmacher of Graiditz, he writes as follows:

“And therefore I’m including a modest gift with this letter, and since it is carved from a stone of the Holy City, it is beloved to Hashem’s people, as it says, ki ratzu avadecha es avaneha. I am therefore sending you a tobacco snuff box, which everyone utilizes constantly, and will therefore be useful for you, despite it being a small gift.”

This column is largely based on an essay by Dr. Yochai Ben Gedaliah.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1038)

Oops! We could not locate your form.