His Secret to Success

With zero charisma and total sincerity, Rabbi Meir Schuster brought thousands of Jews back to their heritage

Photos: Mishpacha archives

Rabbi Meir Schuster ztz”l was always a mystery to me. Not long after my wife and I arrived at Ohr Somayach in the summer of 1979, Rabbi Schuster ztz”l began asking us to host guests on Leil Shabbos. On Thursday night, the phone would ring, but when either I or my wife picked it up, there would be silence on the other end. Eventually, I learned to respond, “Is that you, Rabbi Schuster?” as a prelude to the inevitable question, “How many can you take for Shabbos night?”

But what I could never figure out is his how someone so shy that he could not initiate a phone conversation with someone he knew could force himself to approach dozens of complete strangers every single day. Yet I knew that he did. My friends and I in the Ohr Somayach beis medrash nicknamed him the Pied Piper. Every day, and often more than once a day, we would gaze out the window and there would be Rabbi Schuster getting out of a cab with a group of hirsute, confused-looking young men in tow, who clearly had no idea where they were or what a yeshivah was, and whom we surmised were asking themselves, “How did I let this fellow bring me here?”

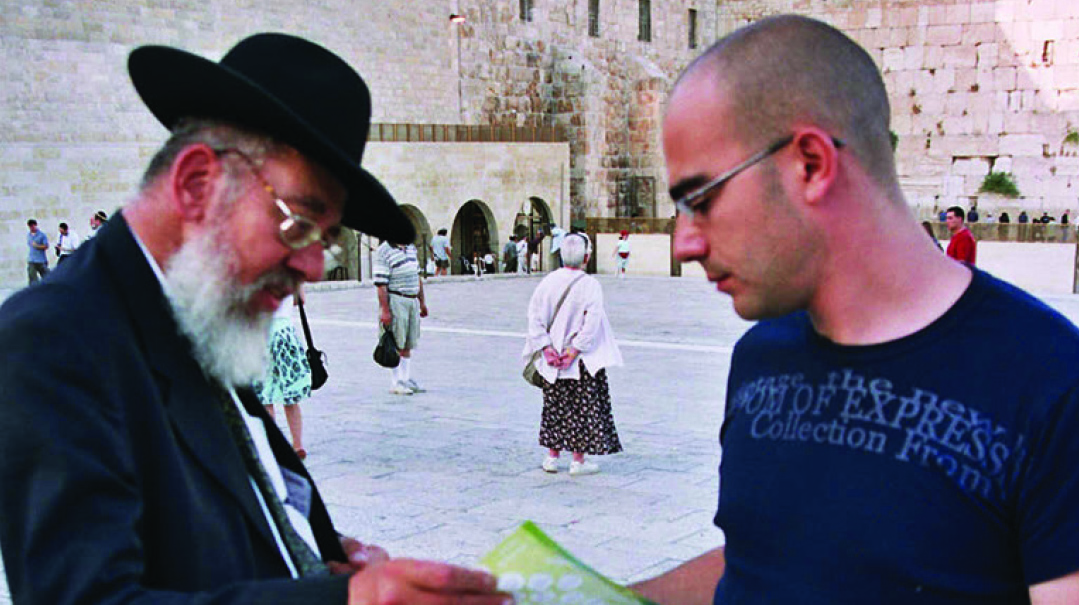

Despite not being the type of person you’d expect to go into sales, Rabbi Meir Schuster, who passed away in February of 2014 at age 71, brought more students to Israel’s baal teshuvah yeshivos than anyone else. For years, the “Man at the Wall” would be at the Kosel every day, connecting to young people, offering to bring them to Torah classes — no strings attached — and setting them up with frum families for Shabbos meals. One of his great innovations was Heritage House, two hostels for men and women that became a popular alternative to the cheap hostels that had been favorites of budget travelers until then.

Granted, most of those whom he brought to Ohr Somayach probably did not stay. But enough did that the dorm was always packed. The late rosh yeshivah Rav Mendel Weinbach summarized Rabbi Schuster’s impact succinctly: “If not for Meir Schuster, the baal teshuvah institutions as we know them today would not exist.” According to Rabbi Dovid Refson, who founded Neve Yerushalayim in 1970, at least one-third of the nearly 40,000 women who have attended Neve Yerushalayim over the decades were first brought in by Rabbi Schuster.

Rabbi Noah Weinberg relentlessly drove his talmidim at Aish HaTorah to achieve more, and spoke constantly of the “power of one” to change the world. When he did, he would invariably point to Rabbi Schuster as proof that it is not one’s natural abilities that are the primary determinant of one’s impact on the world, and that such deficiencies as we possess are not nearly so great limitations as we imagine them to be.

Rabbi Yehudah Silver was a high school classmate of Rabbi Schuster’s and remembers him as a “very shy and withdrawn teenager, who found it almost painfully difficult to communicate or to make connections with people.” Yet a quarter century later, when Rabbi Silver moved to Israel to join the hanhalah of Aish HaTorah, he witnessed “the most amazing transformation he had ever seen in his life.” That same shy teenager was now approaching dozens of strangers a day.

But that is not exactly correct. There had been no “transformation.” Reb Meir was still shy, frequently tongue-tied, and awkward. But he had not let those qualities define him.

“He was, in my opinion, the most successful person who ever lived,” says Rabbi Dovid Refson of Rabbi Meir Schuster, meaning that he did more with the particular kochos hanefesh, the personal strengths with which he was blessed, than anyone else. And that’s why, even seven years after his passing, it’s so important to “solve” the riddle of Rabbi Meir Schuster, or, at the very least, flesh it out as clearly as possible. For Rabbi Schuster’s life carries a message of hope for each of us and can serve as a spur to greater confidence in what we can achieve.

He Saw Through Them

I embarked on writing Reb Meir’s biography, A Tap on the Shoulder: Rabbi Meir Schuster and a Magical Era of Teshuva, which is due to be released by ArtScroll next week, as a labor of love. My wife and I were in the minority of those who entered baalei teshuvah yeshivos and seminaries between the years 1972 and the beginning of the millenium — the years Reb Meir “worked” the Kosel — who were not brought in by him. But we were very much part of the “magical era of teshuvah” in the biography’s subtitle. A Tap on the Shoulder relates dozens upon dozens of stories of people whose lives were upended forever by their first encounter with Rabbi Schuster, and as such, it is a major slice of the history of our generation of baalei teshuvah.

The achievement of Rabbi Meir Schuster is deeply intertwined with a particular historical moment. The late ‘60s and ‘70s may have bequeathed us many pernicious legacies in terms of drug use and the breakdown of traditional morals, but the generation’s pursuit of authenticity and quest for experience sent tens of thousands of young Jews on round-the-world journeys of self-discovery. And most of those eventually ended up in Jerusalem at some point in the journey.

Students graduated college without the kind of debts so common today, and in many cases after having actually learned something that would facilitate earning a living one day. The general affluence of post-war America left recent graduates confident that they could take a year or two off to travel the world without endangering their futures.

Having spent time in Buddhist monasteries learning mantras or having watched natives in Burma (today Myanmar) sacrificing pigs to their harvest gods, they could not very well reject an invitation to learn something of their own religion. Yeshivah or seminary was just one more occasion of self-exploration on the journey.

At the time, Alex Haley’s Roots lent impetus to the exploration of personal history. And Jewish pride was at its peak in the wake of Israel’s stunning victory in the Six-Day War. In those days, most Jewish backpackers still had two Jewish parents. When they sought to explore their own roots, those roots were Jewish ones. And so it happened that thousands who rejected authority and sought freedom from all traditional mores ended up adopting a more rigorous and demanding life than any lifestyle against which they were rebelling.

The stories of the baalei teshuvah from that era demonstrate how imperfect is our understanding of the Jewish soul, and how utterly futile are all our efforts to predict who will become religious and who will not on the basis of external appearances or political opinions.

And that’s precisely where Rabbi Meir Schuster had his greatest advantage: He didn’t see externals, only the Jewish soul inside. His wife, Rebbetzin Esther Schuster, put it best: “He saw through them and they saw through him.” Where others might have seen only the long hair, scraggly beard, and bedraggled clothes of young adults exploring their identity, Rabbi Schuster saw nothing besides Hashem’s beloved child, the pure, unsullied pintele Yid standing before him.

And where an outside observer might have seen a gangly, decidedly uncool, inarticulate figure, thousands of young Jews saw someone who wanted what was best for them more than they did for themselves. His sense of urgency when he asked them whether they were interested in knowing more about their Judaism did not escape them. Nor did his pain if they responded in the negative. Young Jews trusted and followed the awkward stranger to a degree they had never trusted anyone before.

Onto His Coattails

It is by now a commonplace notion that Meir Schuster was the least likely person to be a central cog in the teshuvah movement. Everyone who watched him in action thought they could do better. Rabbi Yom Tov Glaser, the famous “surfer rabbi,” used to see Reb Meir walking at breakneck speed through the Old City, with a young Jew in his wake struggling to keep up, and think to himself, “Talk to them. Carry on a conversation.”

But those who thought they could do better were wrong. A veteran kiruv professional was at the Kosel one Friday night trying to convince a couple to experience a Shabbos meal. The man seemed interested, but his companion insisted they should return to their hotel. Then Rabbi Schuster came over, and said, “So you want to go for a Friday night meal?” This time it was the woman who immediately said yes.

Adam arrived at the Heritage House just before Rosh Hashanah of 2000, when it was almost empty because of the outbreak of the Second Intifada. Adam was both very smart and more than happy to engage in debate. But he declined all suggestions that he attend a class at Aish HaTorah or Ohr Somayach. No less than three people, including one described by the then-manager of the men’s hostel as “the most cheerful positive Jew on the face of the planet,” tried without success.

Then, as Adam headed out in the morning to go to the Israel Museum, Rabbi Schuster walked in. When Adam told him where he was going, Rabbi Schuster replied, “No, you should go and check out a class at the yeshivah.” To which Adam responded meekly, “Okay, that sounds like a good idea.” Adam returned to Heritage House that evening elated and committed to going back to the yeshivah the next day.

When Adam was asked by the manager of Heritage House why he had acceded to Rabbi Schuster’s suggestion that he go to a lecture at a yeshivah, after having already rejected that suggestion out of hand at least three times, he explained, “I have never met anyone in my life with such a passion for something, such a love. I had to find out what this guy is so excited about.”

The only plausible explanation of Rabbi Schuster’s success is siyata d’Shmaya. Rabbi Sender Chochamovitch, the founder of Binyan Olam, a yeshivah for Spanish-speaking baalei teshuvah, once proposed to Rabbi Avraham Edelstein, the director of Heritage House, the idea of opening up an additional Heritage House hostel for Spanish speakers. The fundraising responsibility would be completely upon him, as would the running of the hostel. If so, Rabbi Edelstein inquired, why did he want the hostel to be under the Heritage House umbrella? Just one reason, replied Rabbi Chochmovitch: to be included in the siyata d’Shmaya of everything connected to Rabbi Schuster.

When the Second Intifada slowed traffic at the Kotel to a trickle, Rabbi Schuster told Rabbi Edelstein that they would have to shift their focus to Israelis. Rabbi Edelstein pointed out the obvious difficulty: Neither of them spoke Hebrew well. But in the end, Rabbi Edelstein did what he always did in such situations: “I grabbed onto his coattails, and relied on the siyata d’Shmaya that always attached to him to carry us forward.”

Chein is always described in the Torah as a form of Divine gift. And despite his awkwardness — no, often because of his awkwardness — Rabbi Schuster found chein with countless young people. Every young woman who arrived with Rabbi Schuster to Neve Yerushalayim always said the same thing, remembers Rabbi Eliezer Liff, the director of the beginners’ program: “I would never get into a car with a strange man.” And yet, they did. The fact that there was nothing glib about his speech, and that he always raced ahead, helped the young women trust him.

Toby Levy was just out of high school and would not talk to any man she did not know. Yet when Reb Meir spoke to her for the first time at the Kosel, she “looked into his face and saw the most sincere person I had ever met. This man is so pure, in a way I have never seen before. I’m absolutely safe,” she thought to herself.

One of the most frequent comments when people describe Rabbi Schuster is: “I felt he cared about me more than anyone ever had.” Rabbi Schuster found Alana Rubin on the steps from the Kosel going up to the Old City and asked her if she had a place to stay. “He was so gentle and shy,” she remembers, “that I could not help thinking about how painful it must be for him to approach complete strangers in this fashion.” And that realization led her to another: “How much he must care about me to subject himself to such torture.”

People tolerated things from him that they might not have from someone else. After the completion of her Birthright trip, Frieda Shapiro traveled to the Old City in search of a hostel she’d heard about that was supposedly free for all Jews. Suddenly, Rabbi Schuster appeared out of nowhere and startled her. When she replied affirmatively to his inquiry about being Jewish, he just grabbed her huge suitcase and began wheeling it to the women’s hostel.

The next day, Rabbi Schuster showed up early in the morning to take her and her friend to Neve Yerushalayim. On the way, he asked her what she was doing with her life, and she told him that she was an actress. She was used to people being impressed when she mentioned her chosen career. Not Rabbi Schuster. “Why would you do that? Don’t you care about your future? Don’t you care about your Judaism?” he challenged her.

She was, not surprisingly, “furiously indignant” at his effrontery in criticizing someone whom he didn’t even know. But she and her friend did go to Neve that day. And while working in the theater upon her return to New York, those same questions kept niggling at her. The next summer she returned to Neve and ended up as a madrichah at Heritage House.

Looking back, she acknowledges that the manner in which Rabbi Schuster grabbed her bag and started rolling it, not to mention his assault on her acting career, should have turned her off to Orthodox Judaism. But it didn’t. Once she had calmed down — which took a while — she realized that no one had ever shown such concern for her neshamah and the family he hoped she would build.

No Doubts

To say that only siyata d’Shmaya can explain Rabbi Schuster’s influence, however, ultimately begs the question: What causes one person to be the beneficiary of so much evident siyata d’Shmaya?. And the answer to that question may be the most important thing Rabbi Meir Schuster’s life can teach us.

To be the recipient of siyata d’Shmaya, one must first believe in it. One of those who frequently accompanied Rabbi Schuster in the 1970s on his daily rounds was always struck by Rabbi Schuster’s firm assurance that his efforts would be greeted with Divine assistance. Even when those he approached slipped through his fingers, as many inevitably did, that only increased his motivation to “try harder, work smarter, and always leave a lasting good impression, like planting a seed to blossom at the right moment.”

Rabbi Dr. Yaakov Greenwald, in his recently published work With Truth and With Love, based on his correspondence with the Steipler Gaon, defines the essence of self-confidence from a Torah perspective: “To the extent that he believes everything is from Hashem and that Hashem wants him to succeed and has granted him the power to succeed, to that extent he will have the confidence to do what he believes Hashem wants him to do.” He could have been describing Reb Meir.

Self-confidence, thus defined, is the very opposite of conceit; indeed, it is the very negation of the ego. His own ego — even an objective assessment of his strengths and talents — played no role in his chosen mission. It was only about being in Hashem’s service. And because he had so little ego of his own, Hashem’s Hashgachah (Providence) shone through him.

That lack of ego manifested itself in many ways — not the least of which was his ability to accept insults and rejection without being discouraged or deterred. Actually, I first met Rabbi Schuster three years before arriving at Ohr Somayach in 1979. Our first encounter was in the summer of 1976, when I was on a sabbatical year between completing law school and commencing practice, studying Hebrew at Ulpan Etzion in Jerusalem’s Baka neighborhood.

He appeared one day during the lunch break, as the twenty-something young men and women in the ulpan sat around on the grass soaking up the sun’s rays and chatting with one another. None, it is safe to say, had any desire to be interrupted in either activity by a gangly religious figure dressed in black. A number of insults and snide remarks were directed in his direction, probably mostly by the young men eager to impress their female friends. I pray that I was not one of them, though it’s hard to be confident on that score.

Two things stick out in my memory from that day. The first is how undeterred he was by the disparaging remarks aimed at him. And the second is that, despite the verbal arrows directed at him, he still left that day with one of the students in tow — a fellow Chicago native. Twenty or more years later, I came across the name of that student again. He had become the rav of a religious moshav.

When philanthropist Dov Friedberg decided to purchase the building for the Heritage House women’s hostel, what attracted him to Rabbi Schuster was the total absence of the word “I” in his conversation. Phrases such as “I made him frum,” were utterly foreign to him. He never spoke of his achievements, and nothing could induce him to do so.

The power of his connection was most readily apparent in his davening. Indeed, that davening was the most outstanding thing about him. As tongue-tied as he was talking to people, his davening was “the least inhibited I have ever seen,” commented one observer. He was always eager to speak to Hashem, often clapping his hands together before starting to bentsh.

“I learned two things watching him daven,” he continued. “There is a G-d in the world, and this fellow knows him well.”

Another person who frequently davened with him at the Kosel, adds, “It was impossible to watch him daven from the amud without turning around expectantly at the end to see whether Mashiach was coming.” One of his regular hosts on fundraising trips to America confesses that he was afraid to walk above Reb Meir’s basement room two floors below — when Reb Meir could be heard in the early morning stomping about and shouting as he implored Heaven to help him return Jews to their Father in Heaven — lest he be singed by fire, like the birds that flew above the Tanna Rabbi Yonoson ben Uziel when he learned Torah (Succah 28a).

Reb Meir never doubted that as long as he devoted himself completely to his particular life mission, Hashem would grace him with success. His mission may not have been a glorified one — not like being the one to introduce newcomers to the depth and wisdom of Torah. But it was absolutely essential, and no only else did it as well.

No Vacations

The “power of one,” of which Rabbi Noach Weinberg often spoke, is in reality the “power of One.” Knowing that, Rabbi Schuster understood that his success would be determined solely by the degree to which he aligned himself to his Divinely assigned mission and dedicated himself to it fully. That recognition drove him ceaselessly, but it also gave him the confidence he needed to push himself as he did.

He never permitted himself a vacation day over a span of a quarter century. Even on Yom Kippur, he davened in a neitz minyan so that he wouldn’t miss curious tourists later on.

Lori Palatnik, who like many of Reb Meir’s “catches,” would go on to become a major figure in the world of kiruv, first encountered Reb Meir on a cold, rainy winter night, as she fled from the Arab hostel in which she had been staying. He was there maintaining his lonely vigil at the Kosel, despite the lack of any passersby. Had he been home in his heated apartment instead, who knows whether Lori Palatnik would have ever gone to a seminary.

The most famous story about Rabbi Schuster also emblemizes his absolute commitment to his mission. On Isru Chag Pesach 5735 (1975), the Schuster’s oldest child, a six-year-old girl known by everyone as Shatzi, was hit by a truck on her way to the local makolet to buy some gum after the holiday. Reb Meir was absolutely besotted with his daughter, who by all accounts was a child of unusual chein.

Yet after a few days of sitting shivah, he became increasingly agitated by the thought of all the young backpackers who would be visiting the Kosel and who might miss their one chance to explore their Judaism due to his absence. He had no doubt that his presence was a matter of pikuach nefesh that would push off the requirement of sitting shivah.

He asked Rabbi Aharon Feldman to bring the sh’eilah to Rav Elyashiv. Rav Elyashiv did not refute Reb Meir’s halachic calculation — indeed, he affirmed it. Nevertheless, he said that Reb Meir’s actions would not be understood and might even harm his subsequent work, and he should therefore continue to sit shivah. But Rav Elyashiv was so moved by the question that he personally went to make a shivah call, despite the fact that he rarely left his Meah Shearim neighborhood.

And that absolute commitment is why, according to one former backpacker who not only went to learn Torah, but who today teaches at Aish HaTorah, “it just seemed the most natural thing in the world to follow him to yeshivah.” A Tap on the Shoulder is Reb Meir’s story, but it’s also that of the tens of thousands who followed him into the unknown.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 865)

Oops! We could not locate your form.