His Pleas Still Echo

For the Beis Yisroel, it didn’t matter if you were a scholar, a cab driver, or a child who knew nothing of Shabbos

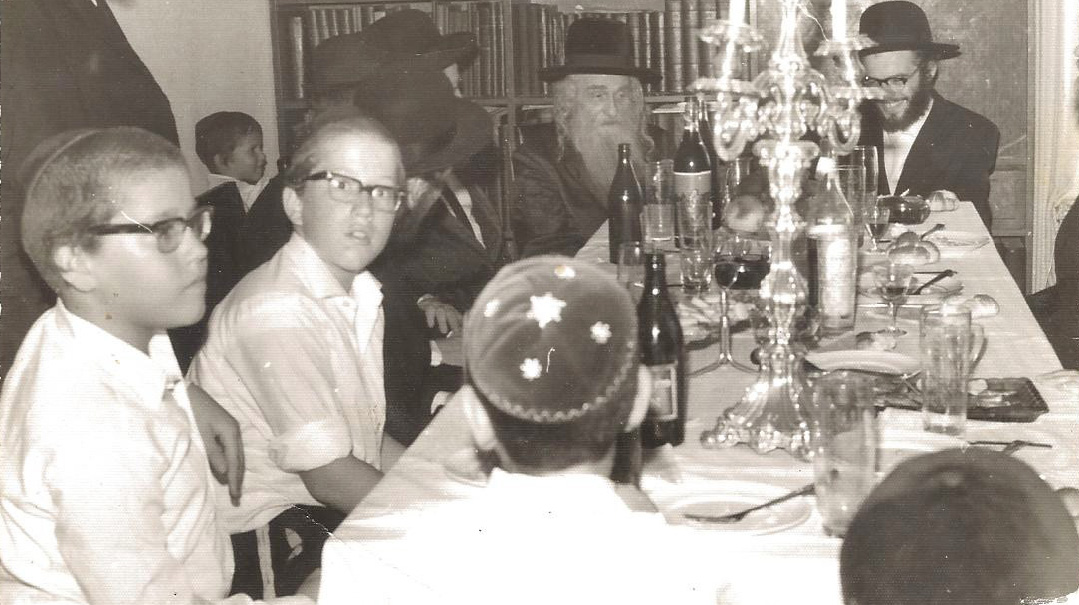

Photos: ArtScroll/Mesorah

I’d never met Rebbe Yisroel Alter, the Beis Yisroel of Gur, as he passed away close to 50 years ago. Yet the passage of time actually made this biography project easier — because the Beis Yisroel, with his immeasurable impact on a nation still reeling, was such a complex personality, such a nuanced story, that it’s only now we can marvel at the precision of a Divine plan that planted him at that juncture in history. With the release of The Beis Yisroel, maybe we can still feel the impact

My friends sometimes make fun of me (which is what good friends do), mocking the fact that I breathlessly claim how each new book is different than any of the previous ones I’ve written and I have never been so inspired/moved/determined/motivated.

It’s an okay joke, but it’s also really true that every story awakens parts of a person they didn’t know existed, pulling them into a different dimension.

I never saw the Beis Yisroel — Rebbe Yisroel Alter of Gur — who was niftar in 1977 when I was just a year old, though we did have a connection which I only learned about two years ago, when I was unsure whether or not this project was for me.

I asked my father for his opinion, and he told me a story.

On a visit to the Holy Land, my father went in to the Beis Yisroel with a kvittel. The Gerrer Rebbe scanned the paper, a smile playing on his lips.

“Drai techter — three daughters?” he asked my father.

Seeing an opportunity, my father suggested that if the Rebbe would bless him with a son, surely it would come true.

The Rebbe nodded. “You will have,” he said.

A year later, I was born, and then it was back to sisters again, five of them in total, bli ayin hara, and no brothers.

In Ger, like in most Polish chassidic courts, wonder-stories don’t impress anyone: As the Kotzker Rebbe said, playing on the words we say in Maariv each night, “Osos umofsim b’admas bnei Cham” (literally, “Who wrought us signs and wonders in the land of Cham”), as “Signs and wonders are appropriate for the children of Cham.”

The story above would be seen as nice, but not much more than that. For stories to be worth anything, they have to obligate.

There are enough such stories, but — in the style of Polish chassidus — they do not obligate in an overt way, and they are not the sort of stories that a teacher can tell students and then neatly sign off with “what we see from here, kinderlach, is the importance of…”

The Lev Simcha, Rebbe Simcha Bunim Alter, the Beis Yisroel’s brother who succeeded him as Rebbe, gave expression to this.

Not long after the Lev Simcha assumed the mantle of leadership, a chassid came in and told the new Rebbe about how his son had been learning in the Gerrer Yeshivas Sfas Emes, and he had developed a serious illness. The Beis Yisroel had assured the father that there was no reason to worry, and the bochur had recovered, showing no signs of having ever been ill.

“I am happy the boy is fine,” the Lev Simcha responded, “but that is not a moifes. If you want to know the real moifes my brother did, it is that he took bochurim and turned them into fiery talmidei chachamim and ovdim — that was his moifes.”

To make a sick person healthy is necessary, of course, but it is not the goal. The goal is to come a bit closer, to work a bit harder, to reach a bit higher

The Imrei Emes, Rav Avraham Mordechai Alter, with his sons, the Beis Yisroel and The Lev Simcha (the Pnei Menachem, his youngest son from his second wife, would become Rebbe after the Lev Simcha)

U

sually, the passage of time makes a difference: It’s much more challenging to write about someone who passed away decades ago than about someone who left the world in the last year. In the latter case, there are family members and talmidim who carry fresh memories, the details still sharp and clear.

In this case, however, the passage of time made it easier. Because the Beis Yisroel was simply too complex a personality, too nuanced a story.

It is only now, half a century after his passing, that the effects of his leadership can first be appreciated, that we can marvel at the precision of a Divine plan that planted a certain type of leader at that juncture in history.

I sat with an older man, a survivor of the camps, and he spoke with typical Poilishe candor and cynicism, speculating that never, since the Baal Shem Tov, did a Rebbe face a more daunting task.

In Poland, he told me, it wasn’t hard to be chassidish. The peasants in the marketplace, the wagon drivers and innkeepers that a person dealt with every day, made a Yid yearn for the safe, warm confines of the shtibel. On Motzaei Shabbos, when they made Havdalah, their hearts sank at the thought that they would have to wait another six days for Shabbos, because it would be six days of darkness and pain. Chassidus — finding ways to be happy, grasping a flame of emunah, believing that the Ribbono shel Olam appreciates simple gestures — was their only salvation.

But in the new world, where streets were named for neviim and there was kosher food in the bus station, where it was all so Jewish, who needed chassidus?

The Beis Yisroel was ready. He knew that the window was small, but he had the right words to reach a heart. He was a master at investing people with dreams, and then giving them the confidence to realize those dreams.

And, I would learn, it had nothing to do with Gur. He was not on a mission to grow the chassidus or add members to the beis medrash. Some of the bochurim whom he drew close did become chassidim, but others did not, and he never asked them to.

Speak to people of a certain age and, chances are, they have a Beis Yisroel story, a moment or encounter that remains seared into their memory, and, in many cases, one that shaped the path they would take in life.

I know that I did not get all of these stories, of course, or even a significant part of them, but some, yes — and each one is enlightening.

At a meeting of the Vaad Hapoel of Agudas Yisrael. (R to L) Rav Pinchas Menachem Alter, Rav Levi Yitzchak Horowitz of Boston, Rav Boruch Sorotzkin, the Beis Yisroel, Rav Leib Gurwicz, Rabbi Dr. Yitzchak Levine, Rav Simcha Elberg and Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach

A

nother difference between this book and others is that the building where it happened still stands. Not just the “old” beis medrash on Rechov Ralbach off Malchei Yisrael, but the beis medrash before that.

Yeshivas Sfas Emes stands near the Machaneh Yehudah shuk. It’s nearly a century old, and it was in that beis medrash that the Imrei Emes, the Beis Yisroel’s father — who had been a rebbe to tens of thousands of chassidim in Poland — led his chassidim during his final years, the room in which the Beis Yisroel’s own reign started.

The room is as it was, not a very big room at all, but the people who filled it then were huge.

There were the striking musical compositions of Reb Yankel Talmud telling the story of extraordinary loss and even more extraordinary faith, of crushing pain and desperate hope and humble acceptance. During the early 1940s, when every chassid in the room was mourning someone — the Imrei Emes himself mourning the majority of his children and grandchildren — Reb Yankel created new tunes, and the men sang Ki anu amecha v’Ata Elokeinu as they had in years past.

The next part to that song would come with the Beis Yisroel’s success. From some, he demanded Shabbos or tefillin, while for others, the goal was the intense avodah of Kotzk of old. He knew his people, and he knew how to speak to each one. Once, the Beis Yisroel sat in his room lost in thought. One of the meshamshim came in and the Rebbe looked up.

“Day and night I sit and think about the words of the pasuk, “V’lo yisa Elokim nefesh, v’chashav machashavos l’vilti yidach mimenu nidach — For God favors not one soul over another, and He finds ways to see that one who is banished is not cast from before Him,” the Rebbe said.

“This is my whole avodah here.”

T

he Beis Yisroel’s vision was broad. He was busy with the spiritual welfare of all Yidden, everywhere, up to date on happenings in litvishe yeshivos, Sephardic kehillos, and moshavim across the country.

He wanted to see the glory of Yiddishkeit restored, and it was with his encouragement that the young rebbes of Amshinov, Belz, Boyan, and others came forward to lead, charged with a mission by the Gerrer Rebbe.

He was a member of the Moetzes Gedolei HaTorah of Agudas Yisrael, paid annual membership in the Eida Hachareidis, and davened with the Sephardic mekubalim of Yeshivas Beit-El, fascinated by all expressions of true Yiddishkeit.

That’s why this book took me well beyond Gur, the stories and memories coming forth from people who had never touched a spodik or heard a rousing march for Lecha Dodi.

The Beis Yisroel led up until his final moment, leaving the beis medrash in the middle of davening on a Shabbos morning for the last time, his levayah held 24 hours later.

His passing came as a shock, because if ever a rebbe was larger than life, it was he — chassidim unable to imagine a reality without him as leader.

Time has passed, but the sense of loss still lingers.

He left over no biological children, but he was the rebbe that the Baal Shem Tov had in mind when the movement was started — a father and mother, a teacher of Torah and healer of souls, wise and humorous, saintly and pure.

Nearly five decades since his passing, people still hear the echo of his voice, his pleading, insistent tone reminding them what a neshamah is and what a Yid is.

In hearts, minds, and homes, he lives still.

Every Man Counts

For the Beis Yisroel, it didn’t matter if you were a scholar, a cab driver, or a child who knew nothing of Shabbos.

The following is an excerpt from The Beis Yisroel: The Life and Legacy of Rav Yisroel Alter of Gur (ArtScroll/Mesorah), by Yisroel Besser

No Yid Is An Outsider Here

One day, the Rebbe was running a fever, and the meshamesh informed the waiting chassidim that the door would not be open for the public that day.

The Rebbe overheard the announcement. “If you close the door and do not let people in,” the Rebbe said, “you will only make it harder for me, because then I will have to go out to them.”

Closing the door was not an option for a rebbe who belonged to the people.

A chassid was mazkir his son, a child who had been hospitalized with an infection. The next morning, the Rebbe saw the father and asked him for an update. “It’s true that you are the father,” he said, “but the daagah, the worry for the child, is mine.”

A young girl from Haifa was, Rachmana litzlan, diagnosed with a dreadful disease. She had to undergo treatments in Shaare Zedek Medical Center, and whenever her parents brought her to Yerushalayim for treatment, her father would go into the Gerrer Rebbe to be mazkir her. Sadly, her situation did not improve.

After a long day in the hospital, the father went to Gur to receive a brachah before returning to Haifa. The Rebbe asked an unexpected question. “Where is the girl now?” he asked. The father replied that his wife and daughter were waiting for him outside, on the street.

“Let us go upstairs,” the Rebbe said, and together, the Rebbe and chassid walked up two flights of stairs to a window from which the street below was visible.

The Gerrer Rebbe, who did not receive women and girls, had the father point him in the direction of his family, and then the Rebbe gave his brachah. Two weeks later, the young girl passed away, and to her mourning father, this was the nechamah: The Rebbe had not succeeded in saving her, but he had succeeded in showing how deeply he cared, in making it personal, and this in itself brought comfort.

The Rebbe did not give only his time, his tefillos, and his energy to the chassidim — he gave them that which was most precious to him. When he was learning Hilchos Shabbos with Rav Moshe Sternbuch, the Beis Yisroel told him that he would have liked to conduct himself according to the opinion of the Chazon Ish in regard to using electricity on Shabbos.

“But if I will be stringent in this area,” the Beis Yisroel said, “the chassidim in Tel Aviv, who know that this is a chumrah that most people do not follow, will say that ‘our Rebbe is a machmir,’ and they will feel like they can view whatever I say as a chumrah. What can I do,” the Rebbe concluded, “if even my chumros must be weighed on the scale of what is good for the chassidim?”

One year on the 5th of Iyar, the day upon which the State of Israel celebrates its independence, the Rebbe was walking fartugs when he encountered Reb Moshe Chaim Knopf, the editor of the Hamodia newspaper.

“Are the other newspapers printing today?” asked the Rebbe, surprised to see the editor heading to work, as on a usual day.

“No,” replied Reb Moshe Chaim, “it is a legal holiday, and the entire country shuts down.”

“But you are printing?” the Rebbe wondered.

“Yes,” Reb Moshe Chaim answered proudly. “The legal holiday does not dictate our schedule, and we print as on every other day.”

The Rebbe did not seem impressed by the answer, and the editor was puzzled.

“Should we be taking off today?” asked Reb Moshe Chaim in confusion.

“Of course you should,” said the Beis Yisroel. “The whole reason that we need Hamodia is only to counter the secular media, to provide an alternative for those who wish to read the news. But if they are not printing today regardless, then why do you have to?”

IN

1949, during the Beis Yisroel’s first year as Rebbe, a new neighborhood was being built. Givat Shaul Beis would house many immigrants, survivors trying valiantly to rebuild their lives in a new country.

The Gerrer Rebbe went to visit the site, walking through the apartments and asking several questions, as if he himself was an interested buyer. He sat with the planners and inquired about employment opportunities for neighborhood residents close to home, and then he met the families settling in the neighborhood, giving his warm brachos to each one.

They were not Gerrer chassidim and the project had no connection to Gur, but they were Jews, worthy of his interest and blessing.

The Beis Yisroel leaving the Sanz-Klausenberger yeshivah in Netanya, following a visit with the Klausenberger Rebbe. He wasn’t interested in boosting his own chassidus – he just wanted to see the glory of Yiddishkeit restored

R

av Yaakov Nissan Rosenthal opened a kollel in Haifa, creating a stronghold of Torah in the heavily secular city.

Though people wondered how Rav Rosenthal funded a kollel in a city without a natural donor base, he would not satisfy their curiosity, saying only that he had a secret benefactor. It was only after the petirah of the Beis Yisroel that Rav Rosenthal shared the identity of his benefactor.

As a small child, the Rebbe had walked into the room of his grandfather, the Sfas Emes. “Ahhh, the investigator is here,” the Sfas Emes said lovingly, referring to his grandson’s tendency to look around the room, taking in the details and asking questions until his curiosity was satisfied.

Now, the prescience of the Sfas Emes’s nickname was realized, his grandson sitting in a room in Geula, but aware of developments across the city. If there was a program for youth, the Rebbe knew about it, and, without his name ever being mentioned, was likely supporting it and influencing its direction.

The Rebbe knew the schools in cities across the country, aware that in the Tzeitlin school in Tel Aviv, boys and girls were separate only during classes, but not during the break time, whereas the nearby Lustig school, comparable ideologically and academically, had only female students. The parents who chose to send to these schools were not formal Gerrer chassidim, but they revered the Rebbe and would listen to him. Equipped with information, the Rebbe would guide and direct each one according to their situation.

During the Six-Day War, the Rebbe called in a resourceful, personable public figure. “Do you remember the days before 1948, when Yidden were still able to daven at the Kosel?” the Rebbe asked. “There were always squabbles about proper separation between men and women, with no one in charge. Now, if the Israeli government will assume control of the Kosel again, we must be ready.”

The visitor reacted with surprise. “Now, Rebbe? In the middle of a war?”

“Yes,” the Rebbe replied. “Go to the chief rabbinate, figure out which ministry is in charge, and make sure that there is a respectable mechitzah in place by the time the public is able to come daven there once again.” The Rebbe handed his visitor an envelope filled with money. “Here,” the Rebbe said, “take this, so that you do not have problems with money.”

Many of the Rebbe’s public activities — such as the successful campaigns to erect mechitzos at the Kosel and in Meron — were conducted anonymously. The Rebbe provided funding, encouragement, and direction, but his name was never mentioned, preferring that the operation be associated with the “front men” he used.

He once explained it by sharing a memory from Poland. There was a period in which some of the Jewish shopkeepers in Warsaw were hesitant to close down their stores on Friday night, feeling that they simply could not afford the loss of revenue. The Agudas Yisrael party formed a Mazhirei Shabbos group, and their representatives would go to the various stores and try to persuade their owners to close and go home for Shabbos.

The Gerrer chassidim participated in these campaigns and once, a shopkeeper protested that he had no reason to close his store, even though it was already past shekiah and Shabbos had begun. “You see,” he explained earnestly, “I am not an Agudah’nik, this is not for me.”

“Here too,” said the Beis Yisroel, “I do not want people to reject these ideas, saying that they are not bound to go along with them because they are not Gerrer chassidim.”

Y

eshivas HaMasmidim had started out as a program for the teenage boys of the old Yishuv, a framework that kept these bochurim motivated through incentive-based learning, gatherings, and trips.

Eventually, the members of that first group of bochurim married and built a kehillah of their own, educating their own families with the approach that had helped them thrive. The Beis Yisroel was a big admirer of the Yerushalmi kehillah, which had met the needs of a younger generation, and he quietly sent them money every year.

During times of war, there were many Gerrer chassidim called to the front, serving in various capacities. One day, the Rebbe overheard two meshamshim talking in the waiting room. “Is there any news from the heimeshe?” asked one, eager for news about the Gerrer chassidim who were at war. “Alleh Yidden zennen heimeshe,” the Rebbe called out.

An American Rav purchased an existing beis medrash from the family of the previous Rav, and he came to the Gerrer Rebbe asking for a brachah.

The Rebbe scanned the kvittel, then asked, “Di ferd hubben geblibben in shtall — Did the horses remain in their stall? Very good.”

It took a moment, but the visitor understood what he was being told in that pithy sentence.

You are a rav of a shul, charged with responsibility for the growth of your new mispallelim. Shouldn’t you be asking for a brachah that they will grow and you will grow along with them?

The Rebbe’s time was sacred; every second of the day had its precise avodah. The door was opened at the scheduled time each day, and one morning, a young Yerushalmi Yid came in.

Even before he spoke, the Rebbe asked, “Aren’t you a melamed?” Yes, the man conceded, he worked as a melamed in a nearby cheder. “Don’t you work now?” the Rebbe asked.

Yes, the melamed replied, but he wanted to speak to the Rebbe, and the Rebbe was only accessible during the hours in which he taught. He had no choice, and he had asked another melamed to watch the boys until he returned.

“Go and teach the kinderlach,” the Rebbe said, “and when you are done, come back, we will wait for you.”

The melamed returned to his class and afterward, he hurried to the Gerrer beis medrash and went up the stairs to the Rebbe’s room.

The Rebbe himself stood by the door. “Ah, come in, we were waiting for you,” he said warmly — showing his appreciation and respect for the time of this one melamed, charged with teaching Torah to one group of Yiddishe kinderlach.

A visit with Rav Yaakov Nissan Rothenthal of Haifa. The Beis Yisroel was his “secret benefactor”

HE

saw every member of Klal Yisrael as his responsibility. The Rebbe paid special attention to children, seeing a boy of six or seven as equally deserving of his time and attention: He was building a future, and that future was theirs.

A chassid was joined by his seven-year-old son as he passed by the Rebbe for a brachah. The Rebbe stopped the line and asked the child what sort of brachah he wanted. “To grow in Torah and yiras Shamayim,” replied the child earnestly. The Rebbe’s eyes suddenly filled with tears. “Sometimes, children have more seichel than adults,” he said. “This child knows what to ask for.”

The Rebbe was visited by Rebbe Hershe’le of Kretchniff, who had brought his young son along. The two rebbes shared divrei Torah, and the Beis Yisroel honored his guest with fruits.

Before the conclusion of the visit, it was time to recite a brachah acharonah, and the Gerrer Rebbe stood up. He came back a moment later carrying a siddur, which he opened up to the correct page and placed in front of the child, so that he could recite the brachah acharonah from inside.

The child, who is today’s Kretchniffer Rebbe, recalls the impression that made upon him. “My father and the Gerrer Rebbe were soaring in different realms, and even the avodah of eating fruit was significant for them,” he reflects, “but at the same time, whatever was taking place in that room, the Rebbe saw a child and an opportunity to be mechanech him, teaching him that one does not say berachos by heart!”

In the heart of the Gerrer Rebbe, there was concern for every group, for every yeshivah, for every settlement… and for every single Yid.

The Beis Yisroel was in Haifa for Shabbos. He davened Minchah and then went for a walk before Shalosh Seudos was to begin. In the courtyard of the home in which the Rebbe was staying, a large crowd waited for the Rebbe to appear — Gerrer chassidim eager for the words of Torah their Rebbe delivered during these exalted moments each week.

But the Rebbe was not coming.

The Rebbe, who was always so punctual, had not yet returned from his walk. Some of the chassidim ventured out of the courtyard to see if the Rebbe was approaching, but there was no sign of the Rebbe or his meshamshim.

The Rebbe was a few blocks away, on one of the main roads of Haifa. He had been walking there with his meshamshim and had crossed the street at the corner. A car had slowed down as they crossed in front of it, but the driver felt that they were not walking fast enough.

In frustration, he had leaned on the horn, honking at the small group.

One of the meshamshim, zealous about the honor of the Rebbe, turned and headed toward the impudent driver, about to lecture him about what he had done, and whom it was that he had honked at.

The Rebbe turned, and with a single look, he indicated that the meshamesh should say nothing. Then the Rebbe himself headed to the driver’s window.

The man rolled down the window, feeling compelled to hear what this man with the luminous face and burning gaze had to say.

“Today,” the Rebbe said, “is the Shabbos. On this day, every single Jew — no matter who they are or where they live — must rest and refrain from doing forbidden actions.”

“We are not dati,” a child from the back seat informed the Rebbe.

The meshamshim wanted to answer, but this time, the Rebbe waved them away. They stood back at a respectful distance as the Rebbe himself answered the child.

“You should know,” the Beis Yisroel said, “that you are a Jew, exactly the same as I am. Bediyuk kamoni. There is no difference between us, and HaKadosh Baruch Hu, the Creator of this world, spoke to you too at Har Sinai and told you about his mitzvos. When you get older,” the Rebbe said, “you will learn what this means, and you will know that you are just as Jewish as I am.”

The father pulled his car over to the side of the road, drawn to continue the conversation. He asked questions, his children asked questions, and the Rebbe responded with wisdom, with humor, and with warmth, captivating them. The conversation drifted from ideology to current events, a general conversation touching on various topics.

In the courtyard, a huddle of Gerrer chassidim wondered where their Rebbe was as the sky darkened above them; at the side of the road, their Rebbe was speaking patiently with a father and his sons.

Eventually, the sky was fully dark and the Rebbe whispered, as if to himself, “I think it is already permitted to drive.”

He bid them a courteous farewell and told them how nice it was to meet them and converse.

The chassidim in the courtyard never did get to hear the Rebbe’s Torah that week, but the Rebbe had shared Torah after all — just with a different audience than usual.

T

he Rebbe had a great appreciation for the simple Jew, seeing the glory of each neshamah. During the days of the Yom Kippur War, Reb Moshe Prager, a Gerrer chassid and journalist, came in to the Rebbe.

The media was adding to the panic in the streets, reiterating that the surprise attack had come at the very worst possible time of year. Since much of the Israeli population was fasting, the pundits wrote, even the soldiers were not in the proper mindset for war. Reb Moshe admitted that he was frightened by these reports, having already experienced World War II and its horrors in his lifetime. He was terrified at the thought of facing another war.

“It happened at the worst time of year?” the Rebbe asked. “No, it happened at the best time of year, when Yidden are at their purest, their zechuyos shining bright, and that is why our enemies will fall in defeat.”

On that Succos of 1973, cold winds blew into the Rebbe’s succah. Someone commented on the unexpected weather, but the Rebbe did not appear to be surprised. “From himmel, they are telling me that I do not sufficiently empathize with the plight of the soldiers on the Lebanese border,” the Rebbe said. “They spend their nights out there in the cold and no doubt, if I felt their discomfort the way that I ought to, then I would not need such reminders.”

A few years after the passing of the Beis Yisroel, a taxi driver picked up a Gerrer chassid and told him a story. Decades earlier, as a young man, he had driven the Gerrer Rebbe, who asked him what he was thinking about as he drove. The driver answered honestly. “I am thinking about getting to the destination as quickly as I can so that I can collect the fare and pick up another customer.”

“But how do those thoughts benefit you?” the Rebbe asked. “Why not use this time to think about ideas that can make your life better?”

“Like what sort of ideas?” the driver asked, intrigued. The Rebbe informed the driver that Rabbi Pinchas Kehati had recently begun to publish a weekly digest of Mishnayos, a perek each week explained very clearly. “If you learn Mishnayos in the morning, before work,” the Rebbe said, “you can review them all day when you are in the car. In this way you can eventually know all of Shishah Sidrei Mishnah by heart.”

The driver turned around to face his passenger, a proud smile on his face. “Today, I am in the middle of Mikvaos, and I already know all of Shishah Sidrei Mishnah by heart,” he said proudly.

A

visitor from Brooklyn came in not just with a kvittel, but also with an envelope of cash. “What is the money for?” asked the Rebbe, as he usually did, scrupulous about using it correctly. If the money came from maaser funds, then it was used one way, and if not, it was allocated differently. “S’iz fahr vus di Rebbe vil — It is for whatever purpose the Rebbe wants,” came the response.

The Rebbe looked up abruptly. “Di Rebbe vil a yeshuah fahr gantz Klal Yisrael — What the Rebbe wants is salvation for all of Klal Yisrael,” he said.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1007)

Oops! We could not locate your form.