His Own Man

Why was Rav Zalman Levine — a disciple of European roshei yeshivah, and the only son of the “Malach” who created a spiritual revolution in 1920s America — hiding in Albany?

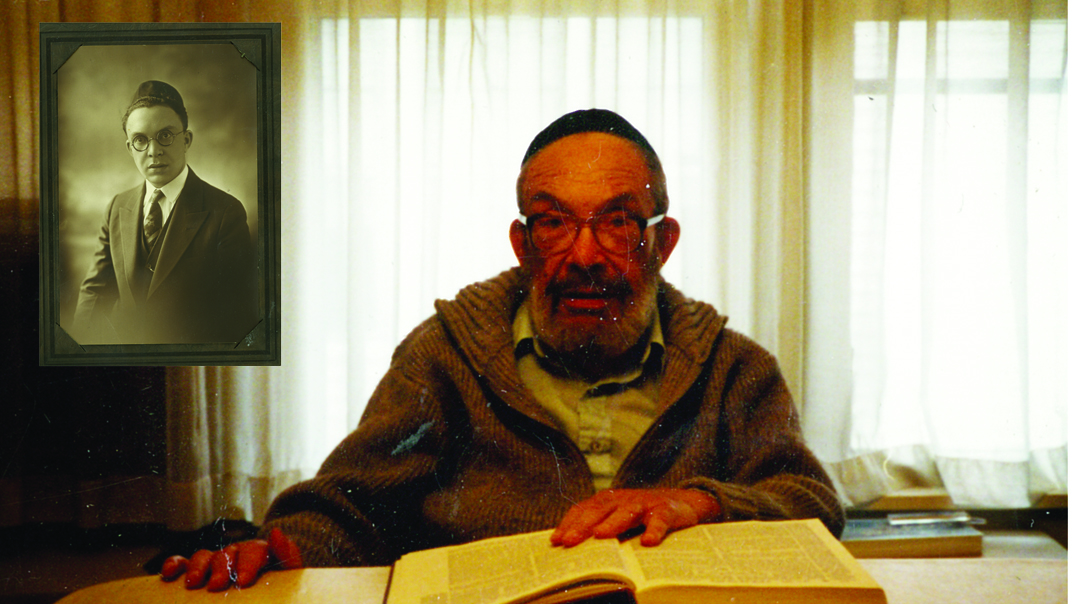

MAPQUEST The Malach’s printed sefer Otzar Igros Kodesh is really just a collection of letters to his son — letters in which the father pours out all his expectations and hopes. So what happened? Why did the Malach’s son fall off the map? Photos: Mordy Gilden Family archives

I' ve passed by Albany so many times the midpoint between New York and Montreal. I’ve davened Shacharis there and enjoyed coffee and a good schmooze with the locals after davening.

But always I missed the real story.

Then several years ago I wrote an article about one of the most intriguing figures in American Orthodox life of the last century the Malach.

His real name was Rav Chaim Avrohom Dov Ber Hakohein Levine: the title referred to his ascetic otherworldly ways but what made him unique was what he did in his angel-like state.

He combined the influence of very different mentors: the intensity and depth of Chabad chassidus fueled his davening while the penetratingly analytical method of Rav Chaim Brisker guided him in learning.

In 1927 this saintly figure arrived in America assuming leadership of a small Bronx shul called Nusach Ari.

Rav Shraga Feivel Mendlowitz always eager to expose his American-born talmidim at Torah Vodaath to the great men of Europe took note of the Malach’s arrival.

These sincere wholesome young boys met the saintly Jew from Ilya near Vilna and they were captivated pulled in by his personality his holy intensity his ideas.

He infused them with his derision and contempt for the American street endowing them with an appreciation for their sacred legacy: they were no Americans they were Yidden.

Their tzitzis blew proudly in the wind as they walked down the street the beards and peyos they sprouted making them visibly conspicuously cheerfully different.

Their parents were worried. The hanhalah of Torah Vodaath was dismayed when these boys announced that they would no longer attend secular classes. Suddenly the term Malach was no longer just an admiring acknowledgment of the master’s conduct it was a scornful label for boys who they felt didn’t know how to behave like regular people. They were “Malachim.”

Years before the Second World War the Malach told his chassidim that the skies over Europe were red with blood and that soon America would be host country to the remnants of Jewry. It was up to them to prepare the ground for the arrivals. Their beards he assured them would cleanse the atmosphere their long coats and Yiddish speech would purify the streets.

The Malachim became a community. They named their Williamsburg shul Nesivos Olam in tribute to the Maharal of Prague who authored a sefer by that name.

On Shavuos of 1938 the Malach died and his talmid Rav Yaakov Schorr took the helm of the kehillah. Many of the original Malachim were swallowed up into a reborn American chassidus led by newly arrived rebbes like Satmar and Chabad. Others remained loyal founding small communiites in Monsey and Williamsburg where they transmitted the Malach’s message and Torah to their own children.

That’s the basic storyline a dramatic fascinating backdrop to the rich American chassidic life we see today.

But there is more detail.

The Malach had a son. An only son.

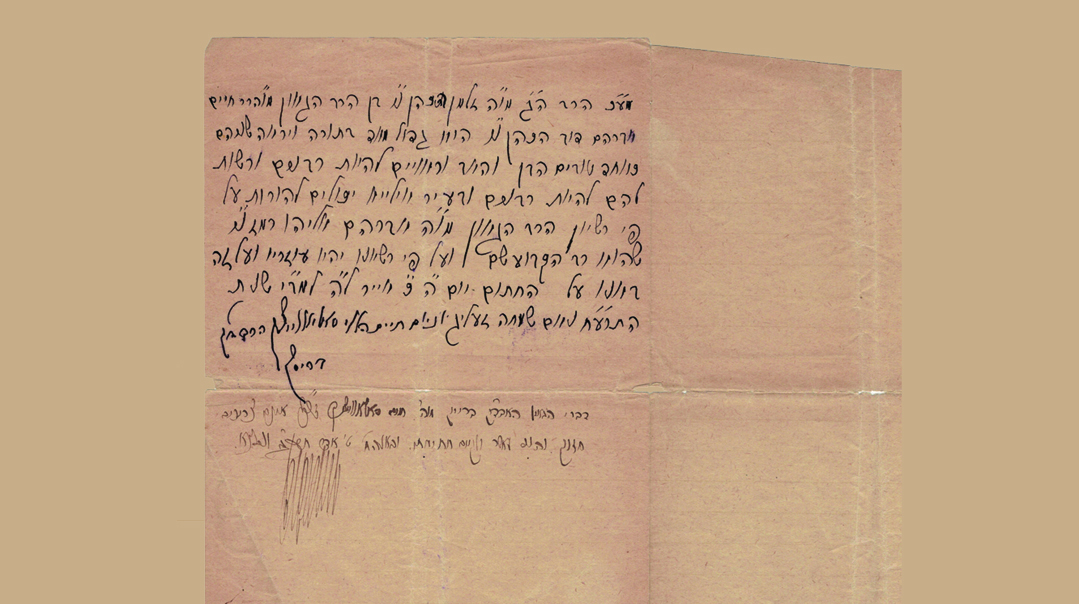

The Malach’s printed sefer, Otzar Igros Kodesh, is really just a collection of letters to his son — letters in which the father pours out all his expectations and hopes.

So what happened? Why did the Malach’s son fall off the map?

I’d often wondered about it, even asked some of the older members of the community.

The answer was vague. Perhaps a slight smile, an obscure nod. I got it. The ones who didn’t know him, really didn’t know him. And the ones who did know him had no real interest in sharing.

So there was little by way of detail or information, no clear explanation as to how he slipped away from the crucible of holiness to sell insurance in Albany.

It was a question expressed by the Malach himself, in one of the printed letters.

You, my son, are a child of Ilya! How is it that you’ve become a man of Albany?

Over the years, we’ve tried to find the answers on our own.

I recall sitting with an older Albany Jew after Shacharis in Beth Avrohom Jacob and asking him the question.

“Zalman,” he told me, “he sure knew his classical music.”

He didn’t say anymore, but the comment was itself a sort of classical music, a solo made all the more glorious by the backdrop of everything that came along with it.

By Design

A few years ago, Rabbi Dr. Yirmiyahu (Jeremy) Luchins, a talmid chacham, scientist, and educator wrote a tribute marking Touro College’s establishment of the Rav Refoel Zalman Hakohein Levine Endowed Distinguished Talmudic Scholar Award.

In his introduction to the piece, Rabbi Dr. Luchins hints at the answer to the question. “Rav Refoel Zalman Levine, who, by his own design, was not well-known outside of a small circle of friends, colleagues, and students...”

The words jumped out at me. By his own design.

More determined than ever to hear about Reb Refoel Zalman, I contacted Rabbi Dr. Luchins, and waited for close to two years for him to find some time to meet with me.

Once, en route from New York to Montreal, I spontaneously pulled off the Thruway and went to the Albany cemetery to find the grave.

I knew enough not to expect an imposing headstone, but what I found was spectacular in its simplicity. Not in the back row, sign of the humble, but near the middle, sign of the unpretentious. The unremarkable headstone marks the graves of a couple. Rabbi R. Zalman Levine, father, husband, and teacher adjoins that of Fanny Horwitz Levine, beloved wife and mother. The only feature to set it apart from the sea of gray sandstone around it is the image of two hands, the sign of Bircas Kohanim acknowledging his lineage, a scion of Aharon Hakohein.

I stood there in silent contemplation, offering a tefillah of my own.

Reb Zalman. Help us know you, understand your life’s work, tell the story you tried so hard to conceal. Ribbono shel Olam, let the heavenly light of the Malach as filtered through his only son illuminate the darkness.

And I walked back to my car, the only visitor at Albany’s Jewish cemetery that day.

Before his rebbi’s 25th yahrtzeit, Rabbi Dr. Luchins finally sat with me to talk about Reb Refoel Zalman and his impact. He spoke. I listened. The narrative he wove wasn’t about stories as much as about authenticity, privacy, humility, and truth.

On one hand, it was a familiar story of so many small towns across America, where exceptional talmidei chachamim sat in small shuls, barely a handful of people able to appreciate the commodities they were selling.

Yet, Reb Zalman’s story had a marked difference: Many of these scholars had never made it to New York, unable to reach the flourishing Jewish communities where they might have been appreciated. Reb Zalman had been there, the Rebbe’s only son, on staff at great yeshivahs, and he’d chosen to leave.

Rabbi Dr. Luchins bears the imprint of someone saturated not just with the knowledge, but the spirit of Torah, the privileged beneficiary of a teacher with so much to give. He is the author of a profound work of translation and elucidation of the zemiros, a master of liturgy and, it appears, the mystical references in each poetic line.

He slowly pulled away the curtain and allowed me to glimpse his rebbi. He also sent me to the others in the small network of talmidim, a tiny group of people who lead very different lives, but who are all aware of each other.

Chuna Leib Boss, one of Reb Zalman’s closest talmidim, has a collection of recordings of the nightly Maharal shiur in which Reb Zalman would tell stories of his father, his rebbi Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz, and so many others, but he speaks little.

Reb Yidel Rappaport in Williamsburg isn’t a talmid, but as a descendent of Malachim, he’s been researching Reb Refoel Zalman for years.

Professor Reuven Sugarman of Vermont is a brilliant, thoughtful philosopher, a close friend and walking partner of Vermont’s Senator Bernie Sanders, and completely dedicated to the memory and teachings of Reb Zalman Levine.

And there is Rhoda, the daughter of Reb Refoel Zalman, granddaughter of the Malach.

Just a few weeks ago, she graciously welcomed me to a small room off the lobby at Albany’s Jewish Community Center.

I’ve interviewed children of great men before, and there is often a certain sense of mild frustration: My father wasn’t appreciated enough… the world didn’t know him… his talmidim kept him away from us…

Here, in the small room, there is only honest reflection, a daughter’s love and reverence.

“They wanted to make my father a rebbe,” Rhoda Levine confides, “my grandfather’s chassidim would come visit him, they would ask him to come back and lead them, but he had different ideas. He had his seforim, his few students. He didn’t need anything more.”

Different Dreams

Rav Refoel Zalman Levine was born in Ilya, near Vilna, in 1900. As a child, he learned with his father, according to the Malach’s exacting methods. Following the Maharal’s approach, he was fluent in all of Mishnayos before starting to learn Gemara. He learned his father’s method of mastering the thought process and memory. A few times a day, his father would challenge him to stop what he was doing and review every single thought that had crossed his mind during the previous five minutes.

As a teenager, he went to learn under Rav Boruch Ber Leibowitz in Vilna, where the Brisker method was transmitted by Rav Chaim’s prize talmid.

Reb Refoel Zalman earned rabbinic ordination from Rav Chaim himself, co-signed by Rav Simcha Zelig Rieger and Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzensky. Like so much else in Reb Refoel Zalman’s life, that paper would remain hidden.

After arriving in the United States in 1927, Refoel Zalman and his widowed father settled in the Bronx. Two dynamic personalities, two accomplished Torah scholars, each with his own vision for their future in this new land, America.

In a relatively short time, the father would have a tight-knit group of devoted chassidim around him, children of the New World attracted to the fire and intensity of the old one. Refoel Zalman was clean-shaven and wanted to learn English.

He got a job as a bochen, testing would-be rabbanim at the Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan Theological Seminary and delivering a shiur in Yeshiva Torah Vodaath.

But they met at the Gemara, father and son, forging a bond of fire, connected by the holiest ideas.

Nearly 30 years old, Zalman made a strong impression on a rav he met at a conference. Albany’s Rabbi Avrohom Yakov Horowitz suggested a match with his daughter, Fanny.

Legend is that she wanted to be close to her family and asked him to consider trying life in Albany. Reb Refoel Zalman, it seems, also believed that his relationship with his beloved father would best be served by distance. Albany was far enough to give him the space to develop, yet close enough that he remained in near-constant contact with the Malach.

Refoel Zalman settled in Albany, but he’d decided he’d never be a rabbi.

He’d seen too much, he explained, too many young men with blank faces and little passion for Yiddishkeit who’d studied for ordination because they coveted the job and prestige, but not the opportunity.

He took a role on the local Vaad Hakashrus, and oversaw the construction of a proper halachic mikveh for Albany, but Zalman Levine worked as an insurance salesman.

Each evening when he came home from the office, he spent time chatting with his wife and then the real work began.

There was the Mishnayos, of course. In a letter written many years earlier, the Malach had enjoined his son: L’maan Hashem, learn Mishnayos with Tosafos Yom Tov for an hour each day. Reb Zalman had mastered Mishnayos before learning Gemara, and kept at it throughout the years, in line with his father’s instruction.

In the JCC office, Rhoda Levine remembers the scene that framed her childhood. “He was always at the dining room table, usually with just one sefer.”

It was either a Gemara, a Mishnayos, or a Maharal.

Sometimes, he learned with no sefer.

Until the end of his life, he toiled to refine and perfect his memory, the clarity of his mind.

BACK TO ALBANY

He considered Rav Boruch Ber his primary rebbi, maintaining a correspondence with the Rosh Yeshivah. Not long after he settled in Albany, Reb Zalman received a visit from his rebbi, who was in America raising funds for Kamenetz. Rav Boruch Ber spent ten days in New York State’s capital with his talmid.

Rebbi and talmid went for long walks around scenic Washington Park Lake speaking in learning and life. Reb Zalman would reflect on and analyze those conversations for the rest of his life.

The mix of mystical and so, so mundane that seemed to hover around Reb Zalman was evident on the day an elderly local scholar passed away. His children had little use for their father’s books, so they turned to Reb Zalman and asked him to find a home for a complete set of Shas, Rambam, and Tur.

Reb Zalman didn’t know anyone who needed it, so he placed the volumes in the trunk of his car and, on a Sunday, drove to New York City and the Lower East Side. He parked near Goldman’s Otzar Hasfarim store and walked around to the back of the car.

As he did, he caught sight of a familiar figure approaching: It was Rav Reuven Grozovsky, the son-in-law of his rebbi, Rav Boruch Ber.

Reb Zalman hurried over to greet Reb Reuven, with whom he’d been close back in Europe, and the two men stood there for several minutes on the Manhattan street corner, reminiscing and catching up.

Reb Reuven had just arrived in America, and even though his apartment was temporary and he hadn’t really gotten settled, he was desperate for seforim. He was headed to the seforim store in the hope that they would allow him to purchase a Shas or Rambam or Tur on credit and he would pay them back slowly.

Reb Zalman led his friend to the car and drove him back to his apartment. Reb Zalman opened up the trunk and started carrying the precious volumes up to the apartment.

Rebbetzin Grozovsky stood there in awe, taking in the scene and perceiving the significance of what was happening — the Divine assurance that Torah would accompany her People from one land to another was being realized. The Rosh Yeshivah, rebbi to a generation, had his Shas.

Reb Zalman, realizing that Reb Reuven would surely try to pay him for the seforim, nodded his farewell to the weeping rebbetzin and left the apartment. He drove back to Albany, to the seclusion and solitude he’d chosen.

In later years, his talmidim would suddenly realize that their rebbi was an intimate and peer of rabbanim who were household names, and always, he waved away their astonishment. It was part of his identity, Zalman of Albany who could drive in to the city and speak with Rav Moshe Feinstein in learning and then drive home and slip effortlessly back into his identity as an insurance salesman.

Members at the Albany shul would listen to Reb Zalman’s perfect tekios, his Brisker exactitude and precision. Few of them knew that as a bochur, he’d been the preferred baal tokeia to Rav Boruch Ber, who appreciated Reb Zalman’s unique ability to blow in accordance with the stringencies of Rav Chaim Brisker. One year, in Vilna, someone asked Reb Zalman if he might go blow shofar for a young scholar, “the brother of Reb Meir’l.” Reb Zalman agreed and followed directions to a tiny hovel, where a couple lived in abject poverty. But the light! Reb Zalman was taken by Reb Meir’s brother, his saintliness and purity and complete mastery of the sugyos they discussed.

“I remember thinking, This yungerman can learn,” Reb Zalman would recall. Years later, the seforim of Reb Meir Karelitz’s brother, the Chazon Ish, confirmed Reb Zalman’s early assessment.

This was Reb Zalman’s holy secret, a man comfortable with angels and people, able to interact with both.

Reb Zalman once explained why he was proficient as a baal tokeia even as his father, the Malach, seemed to struggle with the tekios.

“My father exerted himself on the recitation of lamenatzei’ach. Then he poured his very soul into saying the pesukim before tekios. Before he even lifted a shofar to his lips, he was drained. Of course my tekios seem to be stronger.”

And people in Albany started to catch on. The insurance man with no beard, who wore a gray straw hat and blue shirts, found that, despite his best efforts, others were drawn to him.

After the passing of the Malach, chassidim would trek to Albany in the hope of hearing a vort or story about their master. Often, they would leave with a sense of wonder at the son he’d left behind.

“My father respected his father’s chassidim, and tried to give them what they were looking for, but he was very much his own person,” Rhoda remarks. “He would become a rebbe, but not to the Malachim.”

Though Rabbi Dr. Luchins is an accomplished scientist and talmid chacham, when he speaks of his rebbi, he seems more a wonderstruck child.

Because to him, as to the children of Albany of those years, Reb Zalman, or Zalman, as he preferred to be called, wasn’t the rav or cheder teacher or shochet; he was the gentle man in shul who commanded respect without trying, who somehow made them crave knowledge, whose questions seemed to open a million new doors, whose answers were testimony to the perfection of Torah.

“My own father was a talmid chacham, and when my parents arrived in Albany, my father quickly connected with Reb Zalman," says Rabbi Dr. Luchins. "They became very close, not just my father, but the entire family. He was that sort of person, we were all drawn to him; he had this way of conveying to my mother that she was important too, this automatic respect he bestowed on people.”

Rabbi Luchins remembers coming home one evening and seeing the familiar sight of his father and Reb Zalman at the table, hunched over seforim.

It was a fast day, he recalls, and when the two adults noticed the child, they quickly closed the seforim in front of them.

“They must have been learning sod,” he recalls, “a Kabbalah work. But when I asked them why they’d stopped learning, Reb Zalman said, ‘We’ll see if you have koach to learn on a taanis when you reach our age.' ”

Rabbi Dr. Luchins trys to illustrate the seamless, perfect Torah of his rebbi, one that fused knowledge and kindness.

His face lights up as he finds the perfect illustration of his rebbi’s “perfect Torah,” one which encompassed knowledge and kindness. At the Pesach Seder one year, Rebbetzin Horowitz noticed that her son-in-law, Reb Zalman, had brought grape juice for the daled kosos, a breach with his own exacting Brisker standards.

“Why didn’t you bring your wine this year?” she wondered.

Reb Zalman said nothing but a nonreligious relative answered the question. “It’s because of me, he knew I’d be here and I don’t keep Shabbos. He is worried that I would render the wine unfit, and so he brought grape juice.”

“That,” says Dr. Luchins, “was Reb Zalman’s world: the desire for real wine, to do the mitzvah perfectly, and the fear of Heaven, which led him to bring grape juice instead. And the thread that bound them, the fact that he didn’t just stay home and have the wine and private Seder he wanted, because he was also machmir with human sensitivities.”

Rhoda remembers her father spinning mesmerizing tales about the good folk of the shtetl, the personalities of Ilya. But in a way, he too was a character in one of those stories. Zalman who knew Shas and sold insurance and sat in shul and listened to others. Zalman who could smile with the children and help young men understand their wives and, with knowledge as the goal and tool, lift up everyone around him.

Young Yirmiyahu Luchins left Albany to learn in Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin, in New York City, but when he came home for a visit, he would sit and learn with Reb Zalman, a talmid of Rav Boruch Ber listening to the child of Albany repeat his rebbi’s shiurim.

“We would come back to our small town after being exposed to the real world, but we knew what we had,” Dr. Luchins remembers. “One Hoshana Rabba night, Reb Zalman prepared for the new zeman with me, so that I would have an advantage in shiur. He suggested that we get a feel for the gemara I’d be learning during the coming zeman with Rashi and Tosafos, and also the Rif and Ran. He gave me the shul Gemara to use and took mine, since he said the letters were clearer.”

On the train back to yeshivah after Yom Tov, the teenager opened his Gemara to review.

“And I realized that my Gemara, the one he’d used that night, had no Rif and Ran in it at all! He’d done it from memory.”

When Rabbi Dr. Luchins discusses common threads between father and son, the Malach and Reb Zalman, he mentions that they both viewed youth as the future, the most effective means of building.

Reb Zalman was a member of a shul, and he noticed that none of the aliyos on Shabbos were given to teenagers — only to adults. He challenged the gabbai who admitted that yes, it was an administrative decision: Since the young men couldn’t donate any money, it was better business to give aliyos to those who might make a pledge.

Reb Zalman left that shul and found another place to daven. Teenagers, in his view, should be the prominent members of the congregation, charged with carrying the torch forward. He wasn’t comfortable davening with those who didn’t appreciate this.

Albany has several university and college programs, and many young students passed through the state capital. As the Malach’s son grew older, he seemed to shift in attitude, formally offering himself to these bright young men.

He would sit after davening and speak with them, that mix of penetrating intelligence and gentle humor. He enjoyed listening so much more than speaking, a slow smile spreading over his face as they would share their ideas.

Everything was on the table. Dikduk and physics and mussar insights were welcome as the traditional shvere Rambam — all questions were holy, every bit of knowledge a tool that might make a Torah concept or halachah clearer.

Unlike the intellectual, who relishes the chance to sound sophisticated, even abstruse, Reb Zalman cherished the insight that would make a pasuk, word, or Talmudic concept simpler, easier to comprehend.

Once, a young boy confided that he found Rashi too difficult to learn, and he didn’t enjoy it.

When he left, Reb Zalman looked at his talmidim. “Rashi is there to make things clearer, easier. If someone finds Rashi hard, it means he has a very bad rebbi,” he said sadly.

Informally, he launched a baal teshuvah program of his own. It had no name, no official schedule and no guidelines for admission. It featured him, the sweet, genial, brilliant older man who valued knowledge, respected people, and had a sixth sense about what they need to hear.

Professor Reuven Sugarman was one of those students. He was introduced by Reb Zalman’s dedicated talmid, Chunah Boss, and was soon invited to join the nightly Maharal shiur. Reb Zalman would sit at the head of his dining room table with a single sefer, speaking — sometimes for just a few minutes, other times for well over an hour. Clarity was paramount. He would share obscure concepts, repeating them again and again, refusing to develop an idea until he was convinced that the talmidim were completely with him, along for the journey.

In time, the professor married and had his own family, and Reb Zalman directed him to move to Monsey, so that his children could benefit from a proper education. On the day before Yom Kippur of that year, Professor Sugarman was astounded to see his mentor, Reb Zalman, appear at the front door.

“I didn’t come to visit you. A move can be a difficult experience and I came to see how your wife and children are doing.”

He had the gentle tolerance of a father toward these sincere young men. Reb Zalman maintained a rigorous daily schedule, learning until late at night and rising at precisely 4:45 a.m. to learn again. One Shavuos night, a sincere, fresh baal teshuvah noticed Reb Zalman stand up and head out after learning for a few hours.

The next day, the young man challenged the rebbi’s “violation” of the minhag. “Don’t we have to stay up a whole night to learn?” the young man asked pointedly, as if in rebuke.

Reb Zalman, whose Shavuos schedule was nearly identical to his rigorous learning schedule of the rest of the year, smiled and shrugged. “It’s hard when you reach my age.”

At the age of 65, Reb Zalman was forced into retirement by company policy, but he quickly found a new job working for the state of New York. His superiors, appreciating his unique combination of brilliance and complete trustworthiness, charged him with an influential position overseeing payroll for state workers.

He continued in that role until the age of 84, when he finally retired and devoted himself to full-time learning once again.

“Last week I started Maseches Makkos,” he mused to a talmid, “and I already finished it. In my old job, it took me longer than a week.”

Before leaving Europe, Reb Zalman had gone to the Chofetz Chaim for a brachah. “If you only realized what a good friend you have in your father,” the Chofetz Chaim remarked.

In time, Reb Zalman realized. The chassidim of the Malach printed their master’s letters to his son under the name Otzar Igros Kodesh. The book is a series of severe, demanding letters from an intense father.

A talmid wondered why Reb Zalman had even kept them — let alone allowed them to be made public.

Reb Zalman shook his head. “If you would have had a father like I did, you wouldn’t even be asking that question.”

In fact, Rhoda recalls, he would read his father’s letters, again and again, throughout the years.

Reb Yidel Rappaport of Williamsburg, a great-grandson of Reb Nechemia Weberman — the Malach’s first chassid — reports that Reb Refoel Zalman met with the Satmar Rebbe, Rav Yoel Teitelbaum, on several occasions. On one such occasion, the Rebbe was vacationing in nearby Saratoga Springs and he asked to meet Reb Refoel Zalman. Reb Zalman came, and the Rebbe asked how it could be that a son of the Malach had no beard.

With retirement, Reb Zalman finally grew the beard, a sort of tribute to his father.

When his wife, Fanny, passed away, he knew a new sort of solitude. For the first time, he would travel away from Albany for Yamim Tovim, reconnecting with old friends and making new ones.

“I remember that my father seemed to enjoy seeing how the wider Jewish community had evolved,” says Rhoda. “When he spent Yom Tov in Crown Heights, his cousin, Rabbi Berel Levy, took him to meet the Lubavitcher Rebbe.”

Over Yamim Tovim in the Lakehouse Hotel, Reb Zalman became fast friends with Montreal’s chief rabbi, Rav Pinchas Hirschprung, who could easily match both his fluency in Shas and his sense of humor.

“Reb Zalman once came back from a hotel that catered to an older crowd and he told me that he’d felt like the youngest man there. Everyone was too old for him,” recalls Rabbi Dr. Luchins. “In truth, he was probably older than all of them, but he had an energy and vitality about him.”

Rhoda drove him to the bank one day and when they arrived, he realized he’d forgotten his bank book. “He was devastated. This was a man whose memory was his most valuable asset. He was broken about having forgotten something.”

He spent more time at home. The talmidim were often there, and he learned with a new sort of intensity, as if savoring the time that remained. Still, he understood his role as a grandfather figure to his talmidim and their families, making time to chat with their wives, to join in their happy occasions.

When children of this reverent young generation would ask for a brachah, he would consent. “Not because I’m worthy, but because I’m a Kohein, and Hashem has given us the capacity to bless.”

He got weaker, and on the 9th of Tammuz, 1992, he was niftar.

The Malachim of Williamsburg and Monsey came en masse to the levayah, Rhoda remembers. She wanted the funeral to have the right tone.

“My father was his own man, the chassidim were part of who he was, but not all of who he was. I asked Professor Sugarman to give the hesped. He understood the totality of who my father was.”

And then Reb Refoel Zalman Levine, child of Ilya, talmid of Vilna, quiet gaon of Albany, was laid to rest in the middle of the local cemetery, a Jew among Jews, just as he’d lived.

The father had worked all his life to purify himself, reaching the level of angel, the Malach.

The son worked hard too, but not to be a Malach. He worked to be human

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 667)

Oops! We could not locate your form.