Herr Rabbiner Comes to Haifa

| January 24, 2023Rav Shimon Schwab referenced the danger he experienced at sea in his sefer Iyun Tefillah

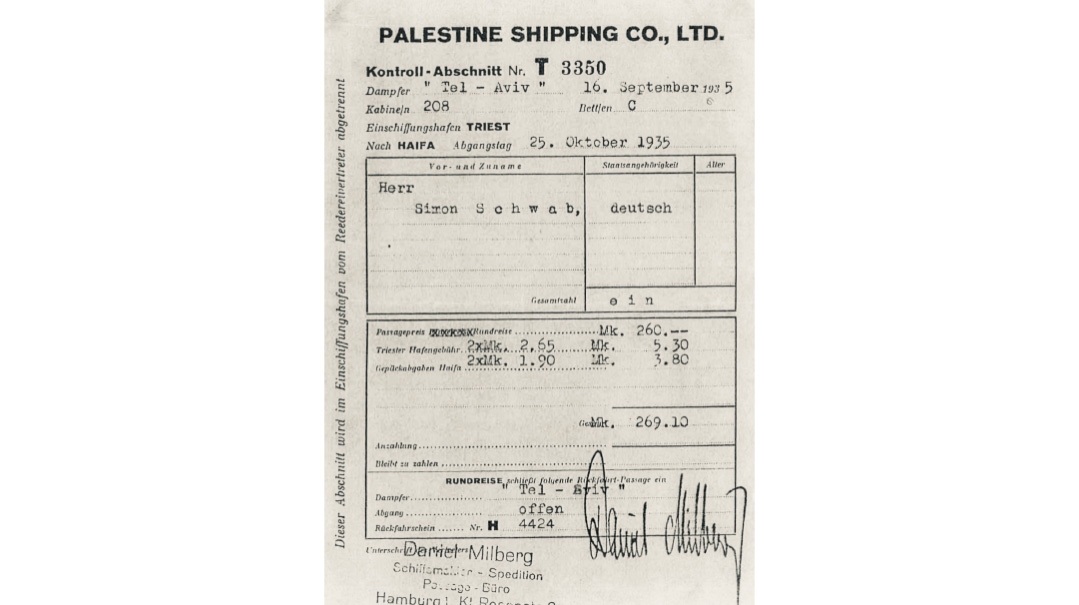

Title: Herr Rabbiner Comes to Haifa

Location: Haifa, Palestine

Document: Ship Ticket

Time: 1935

The rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in 1933 led to a wave of Jewish emigration from Germany. Until then, over a half a million Jews resided there; by the end of 1939, that figure had shrunk to about 200,000. As conditions progressively worsened, nearly 100,000 German Jews made it to the United States, some 50,000 to England, and an additional 100,000 to other Western European countries (many of whom fell victim to the Holocaust when those countries were occupied during World War II).

Another 55,000 were able to receive British Mandate immigration certificates to Palestine. On August 25, 1933, the Haavarah (transfer) Agreement was signed between representatives of the Jewish Agency and the Nazi government. Though this provision generated controversy at the time, it facilitated the safe passage of German Jews to Palestine together with some of their financial assets. German Jewish refugees established communities of their own in Yerushalayim (primarily in Rechavia), Tel Aviv, Haifa, and around the burgeoning Yishuv.

The emerging Yekkish (German) community in the Hadar neighborhood of Haifa soon sought a German rabbi. One of the candidates invited to audition for the position was Rav Shimon Schwab. Having grown up in Frankfurt and studied in Eastern Europe in the great yeshivos of Telz and Mir, he was serving as the district rabbi of Ichenhausen, Bavaria, and the surrounding villages.

The worsening situation had him seeking an escape route for his growing family. His attempt to open a yeshivah in 1934 lasted one day, as the local Nazi rabble rousers threatened violence. A rabbinical position serving yekkishe landsleit in the Holy Land sounded like a good prospect, so Rav Schwab set sail for Eretz Yisrael on September 16, 1935. Just one day earlier, the Reichstag had convened and passed the notorious Nuremberg Laws, which stripped German Jews of their citizenship and formalized their legal status as outsiders in their own country and society.

The ship docked on October 25, and the 26-year-old rabbi spent the next month among the fledgling community in Haifa delivering shiurim and speaking from the pulpit. The community was taken by him and offered him the position, but were unable to pay a salary. Instead they offered him a rent-free apartment near the shul, and proposed that he seek out an educational position at a local school to support himself. Since he wanted to be a congregational rabbi and not a school teacher, Rav Schwab politely declined and returned to Germany and sought alternative positions that could facilitate his departure.

In the summer of 1936, Rav Schwab learned that Rabbi Leo Jung was spending the summer in Zurich, Switzerland, and traveled there to meet him. Rabbi Jung was impressed by the young rabbi and recommended Rav Schwab for bringing vacant rabbinical position in Congregation Shearith Israel in Baltimore, known as the Glen Avenue Synagogue. Rav Jung used his personal leverage to secure the position for Rav Schwab.

He arrived in the summer of 1936 for a trial Shabbos in Baltimore, and he successfully delivered sermons in his rudimentary English as well as shiurim in Yiddish for the elder members. He was told that the board would arrive at a decision immediately following Rosh Hashanah, so Rav Schwab returned to his community in Ichenhausen for what would be his last High Holidays in Germany.

Several days after Rosh Hashanah he received a two-word telegram: “Unanimously elected.” Though he knew what elected meant, he wasn’t familiar with the word "unanimously," so with great apprehension he consulted his German-English dictionary and then recited the brachah of hatov v’hameitiv. When he finally arrived in New York on December 24, 1936, his life had been spared, and American Jewry was to gain one of its greatest Torah leaders of the 20th century.

A stormy sea accompanied Rav Schwab on the journey to Palestine. He referenced the danger he experienced at sea in his sefer Iyun Tefillah when discussing yordei hayam who are required to recite hagomel.

And I myself experienced this when I traveled to the Land of Israel at the end of 1935. There was a great storm with crashing waves, and the ship was tossed about like a drunkard. I was in great danger and desperately clutched an iron bar for 20 hours straight so as not to lose my balance. Due to the danger, I was unable to don tefillin that day. When we arrived safely at the port of Haifa, I recited the blessing of hagomel with great kavanah.

The Yekkehs Are Coming

Though the term’s origins are unclear, German Jews had been referred to as “Yekkehs” since the 19th century. It may have evolved from the German word Jacke (jacket), when German Jews adopted the short European-style jacket, while Eastern European Jews retained longer attire. The term was popularized in the 1930s during the Fifth Aliyah, which was sometimes referred to as the Yekkeh Aliyah, and the German dialect they spoke was nicknamed “yekkish.” The Eastern European immigrants in Israel generally used the term in a derogatory fashion, and it was even said that when spelled out in Hebrew, the word Yekkeh was an acronym for “Yehudi kesheh humor” (Jew with a challenged sense of humor).

Thank you to Rabbi Gavriel Schuster, Boruch Englard, and Camp Munk legend Elie Schwab for their assistance in the preparation of this column.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 946)

Oops! We could not locate your form.