Here I Mourn

There are places that epitomize the destruction: Six writers share the location in which they touch the Churban

The Silent Cry

Riki Goldstein

The door swings open, and we step over the wooden threshold from the sunny Swiss village into another world: an ornate, perfectly preserved shul. I’m taken by surprise by the hushed, rarefied air of the sanctuary, so beautiful and so old, now silent from the echoes of sung and whispered prayers.

We walk forward down the aisle on the stone floor. Everything still stands in place: an impressive aron kodesh painted blue and gold, a pulpit in marble, an ample bimah in the center. Sconces filled with tall white candles hang down….

Above the aron, the morning sun streams in through a circular stained glass window. The ceiling rises above us…. The shul has been recently repainted and is in beautiful condition; all that’s missing is the congregation. It’s an emptiness that tugs at the heart.

—“Swiss Accounts,” by Riki Goldstein, Mishpacha, November 6, 2019

I grew up in the embrace of a beautiful shul where my family had strong roots. This gave me a sense of familiarity and belonging in shul, and a deep attachment to the davening.

On that sunny morning, in the two Swiss villages of Endingen and Lengnau, the shuls beckoned me into a time capsule — the skin and bones of a living, breathing community, now reduced to nothingness. I could touch the gilded columns and the marble and the velvet, the notice boards and charity boxes, sit on the seats in the ladies’ gallery. I could imagine the hardworking Jews who’d given all they could to build themselves a glorious beis knesses, back in 1847.

I stood in the space they had consecrated and longed to join the swell of voices that had once reverberated here — but there was only silence.

With the softest of hands and a molten heart, I caressed the shtenders and whispered a prayer. The visit ended when we backed out respectfully and locked the heavy double doors, leaving the beautiful shul to its sleep.

Our next stop was a shul housed in the tallest and most impressive building in the hamlet of Endingen. In 1761, 245 Jews lived here, by 1850, 990 are recorded. The entire village had no church — only a shul.

This shul too is impressive, with walls painted a dusty pink, regal arches, and a beautiful painting rising up above the aron kodesh. There is a marble lectern next to the aron. The paroches is an intricate one, embroidered by the women “with all their hearts,” for the shul’s dedication in 5611. Yet, the aron hakodesh stands empty. (ibid.)

Where hundreds once stood, as waves of “Barchu” and “Amen” rippled through the air with Swiss decorum, only something subtle yet special remains in the air. A list penned in black calligraphy of the “mizmorim” recited on special days still hangs at the front of the shul, with the name of its donor in silver letters. There’s a red velvet couch that held dozens of Moishelas and Shloimelas at their bris milah. The hand-embroidered paroches hangs over an empty aron kodesh; the shul seems to sigh in a heavy silence.

We daven a little, offering the shul a small comfort with the familiar words of “Mah Tovu,” and then we leave it behind.

Scattered across countries, towns, and villages, some forsaken shuls are like these, gloriously preserved, as if the chazzan could call out “Barchu” any minute. Others are in ruins, or, maybe worse — turned into mosques and museums.

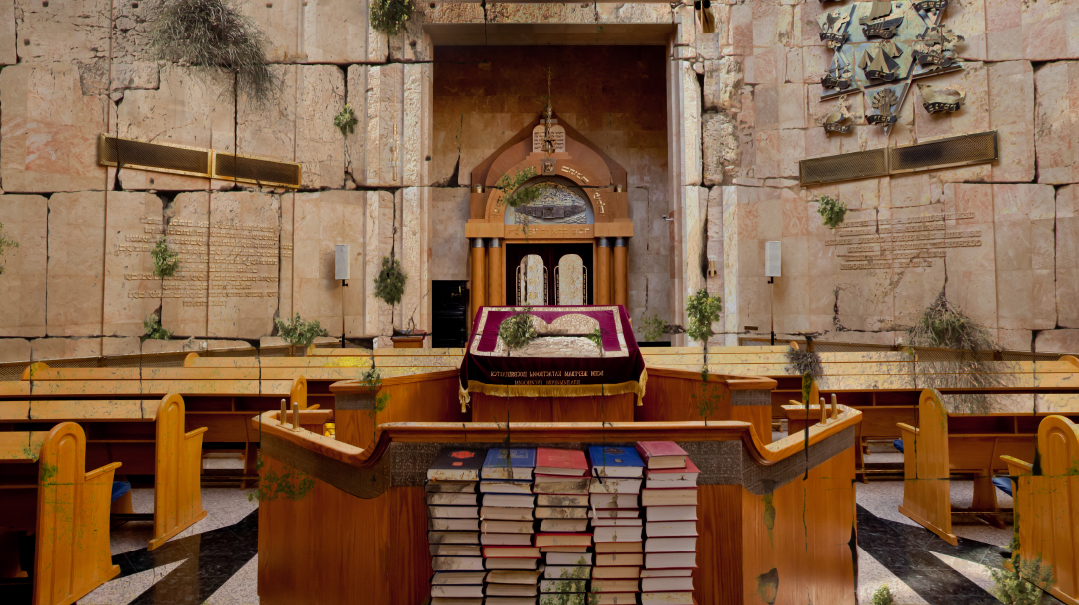

And in Yerushalayim, at the center of the Earth, the most glorious shul of all time, where every Jew felt his heart open and his soul expand in prayer, also stands in ruin, silently weeping for a time that was — and awaiting what will yet be.

The Desolate Desert

Dina Lev

We landed in Phoenix on Monday morning, the arid landscape as foreign as if we had landed on Mars.

Never in my wildest dreams did I imagine I would have a child in a psychiatric inpatient treatment facility, but I did. When they invited us for Family Week, we packed our bags and went. It was the third day of Family Week, and we four families sat in a circle in that small room, peeling layer after layer of pain, supporting each other through the process.

As we stepped outside for some fresh air and solace, we caught sight of the setting sun in the Arizona desert. It seemed that a sun with a neon pink glow like this one must surely be hydrated by the thousands of tears that irrigate the Arizona sand. What else but the desert could be vast enough to hold that much pain? How many tears are absorbed every day by that silent sand?

Each day we processed another piece of the pain that is unique to families dealing with mental illness, until our insides mirrored the ache of the barren land outside; we felt its dryness in our throats, the unsaid words caught inside.

Marla, the group facilitator, went around the circle asking each couple how they might connect and heal after the day’s draining experience. Mark’s wife suggested that they take a drive through the desert, and suddenly we all felt the air suck out of the room as he answered in a hollow, distant voice, “Oh no…the desert depresses me…it’s so desolate…”

The room collectively caught its breath, and we held the silence reverently. No one expected it, least of all from stoic Mark, but once the words were out, we could not un-see the image.

The sadness and the endlessness became the sound and feel of galus. The aching longing of that desert, soaked with echoes of the pain within it, became the symbol of our national angst, mixed with the overarching pain of an entire world, estranged from its G-d. That desert is where my mind goes when I try to hold the vacuous, endless stretch of galus, peppered with glorious, deeply hued moments of beauty. It is what I see when I think about a deeply lost world trying to find its way and the beauty that comes from that struggle.

I think about the cactus plant, cousin to the national fruit of the “am k’shei oref,” and his upright back and stiff neck, which survives by retaining water in its thick skin.

I think about pain, about strength, about beauty, but mostly I think about longing, as vast as the open desert road.

Valley of Lights

Rebbetzin Aviva Feiner

I held on tight to my seat as the #2 bus careened out of Shaar HaAshpot. It swung as it rounded the corner, once again miraculously clinging to the narrow mountaintop road. I exhaled, my eyes still wet from our Motzaei Shabbos Kosel tefillos.

Then I noticed the lights twinkling in the valley below. I turned to my husband, tears filling my eyes again. “Shouldn’t that be where the Kohanim live?”

While there are stalwart Jewish families living in the valley from which the Gichon waters nourished the gardens of Shlomo Hamelech, it’s not their lights that are currently illuminating the valley in an array of color.

The square houses below contain children being educated to destroy my family, being indoctrinated to hate me. They are taught that my city is theirs, and that I have no right to claim her love for me and my love for her.

The aqueduct built by Chizkiyahu Hamelech, which brilliantly diverts and protects the waters of the Gichon, is known in our Torah as the Shiloach. And thus the name of the Arab village I’m looking at is Silwan.

Seeing the lights below is a harsh reminder that the Wall I just visited is but a remnant, that the hallowed area behind it hosts a dome that does not pay tribute to Hashem Elokei Yisrael.

There are no Kohanim rushing to serve, or Leviim scurrying to sing. Yet there are hardened precious Jewish sons, laden with ammunition and cumbersome vests, valiantly and proudly defending my opportunity to shed a tear in the place my ancestors dreamed of.

We dream, we yearn, and we pine for far more than just a holy Wall, “because her servants wanted her stones” (Tehillim 102). We long for all of her sacred stones to be rebuilt in their full glory. V’sechezenah eineinu b’shuvcha l’Tzion b’rachamim. May we merit to soon see the time when the Kohanim will ignite the light that shines over the Shiloach valley and illuminates our Holy Land.

Nameless

Faigy Peritzman

Tishah B’Av, 5755. Johns Hopkins University.

The air was muggy and still, like the world was subdued. The winding cement path leading to the Hillel house was illuminated by garden lights. I hurried along, feeling like I was the only creature daring to move on that hot, humid night.

I’d been learning with students from Johns Hopkins for about a year. Sarah, my steady chavrusa, had asked me to come by Tishah B’Av night.

“We’re having a special program. It’s a summer term so there won’t be that many students, and it would be great if you could be there.”

Opening the door to the kosher cafeteria, the scene I saw added to the twilight zone feeling I’d had walking up the path. The lights were off, the room lit solely by a trio of candles flickering on the floor. A circle of students huddled around the candles. In hushed voices, they took turns reading names of those who’d perished in the Holocaust.

Sarah looked up and saw me and motioned to the place beside her. I sank to the floor as the voices continued.

Selma Lowenstein… Selena Lowes… Sophia Lowinski… Stephen Lowssrey…

The voices were muted, their expressions serious. This vigil would take hours.

It was eerie. It was beautiful. There was something so innocent about their behavior. It was a testimony to their consciousness, their Jewishness, their sense of responsibility. They knew little about Tishah B’Av; this was how they were expressing their loss.

The names marched on.

Sabina Veinbersh… Sarah Veingott… Zigfried Veingott…

Time felt as though it stood still. I felt an incredible despair overcome me, a lump in my throat that threatened to choke me. I wanted to stand up, to walk around this small circle of Yiddishe neshamos and ask each one of them: What’s your name?

To that blonde-haired girl in jeans who was now intoning names, what’s your name? Your mother’s Hebrew name? To the dark muscular guy with tattoos round his wrist, what’s your Hebrew name? Has anyone ever used it to call you up to the Torah?

As the students took turns solemnly chanting names of those lost in the Holocaust, I realized I was mourning those six million — and millions more, all the lost Jewish souls who remain nameless today.

Narrow Spaces

Gila Arnold

We were up north on vacation, and my husband had heard that he could find a Shacharis minyan in the mixed religious/masorati yishuv five minutes down the road. He arrived at the shul at what he’d been told was the minyan’s starting time, and found only three other men there.

“Will there be a minyan for Shacharis?” he asked one of them.

“Bizchutcha! In your zechus!”

Taking this as a warm way of saying “yes” (rather than, as it turned out, an expression of unfounded optimism), my husband took out his tallis and tefillin and prepared to settle down. Not wanting to take someone else’s spot, he asked the man if there was any particular seat he should sit in.

“Sit wherever you want!” the man responded magnanimously. “You’re a guest.”

Cheered by the hospitality (though still wondering when the other men would arrive), my husband chose a seat in the large, empty room and began to learn. A few more men trickled in. Ten minutes passed, then fifteen.

Suddenly, he was distracted by some shouting a few rows away.

“Why are you sitting here?” The man who’d been so welcoming to my husband was now screaming at another congregant, clearly a regular. “This isn’t your seat! You’re always sitting in someone else’s seat! Why can’t you stay in your own makom kavua?”

“You’re always changing my seat around!” the other man yelled back. “You tell me to go here, and then there — why can’t you just let me sit where I want?”

“Sit where you want?!” the first man spluttered. “You can’t do that! These seats belong to other people!”

From the way they were going at it, my husband expected the crowds to come pouring in any second, to fill up every available spot in this sanctuary built for 60, and give some context to the men’s argument.

But, alas for them and for my husband, no more than eight men had turned up when the first man abruptly put the argument on hold and went up to the amud to begin brachos. Shacharis started and ended without a minyan. And when it was over, the two started up again.

“Next time, make sure you sit in your own seat!”

“Don’t you tell me what I can do! Give me a good seat and I’ll sit in it!”

Clearly, this argument had a long and loaded history, and the quarrel felt eminently reasonable to the two combatants. But to an outsider watching them fight over a single seat in a large, empty shul that couldn’t even draw a minyan, it was a ridiculous sight — it would have been amusing, if it hadn’t been so sad.

One of the miraculous characteristics of the Beis Hamikdash was that the Jews were omdim tzfufim u’mishtachavim revachim — no matter how many people were packed inside the courtyard, there was always ample room for each one.

If this feeling of expansiveness — both in the physical sense and in the emotional and spiritual one — was a quality of the Beis Hamikdash, what, then, should we call its opposite?

Shards of Light

Elana Moskowitz

Generally, busy Jerusalem intersections don’t evoke much emotion. Honking traffic, making or missing the light, and gridlock aren’t usually the stuff of deep sentiment. Until recently, the intersection of Golda Meir and Givat Moshe, a congested area on my way to work, conjured the same emotional response as most busy city corners: none whatsoever.

But for the last few weeks, this unremarkable juncture has been my reminder of how things can instantly fall apart irreparably, and of the courage it takes to accept what coalesces in the aftermath.

I meet Avrumi at a family sheva brachos. He’s made the trip in from the north, an arduous two-hour bus journey to the Jerusalem family hosting the simchah. And he convinced a musical friend to accompany him, because “How can you have a sheva brachos without a guitar?”

Avrumi is friendly, his face imprinted with a perpetual smile, and he participates enthusiastically in the simchah, singing heartily and delivering a confident devar Torah to the assembled.

He’s also clearly impaired. His speech is deliberate and occasionally hesitant, his affect is off. And something in his radiant smile is too open; the guardedness and reserve expected of a 25-year-old is conspicuously absent. Soon the backstory emerges.

There was an accident at a busy Jerusalem intersection, and 14-year-old Avrumi was hit by a speeding vehicle, tossed far across the teeming thoroughfare. Hatzolah’s valiant attempts at resuscitation weren’t successful, and they prepared to declare the worst. Suddenly a stranger approached, and implored the paramedics to continue, to delay the seemingly inevitable. Hatzolah acquiesced, and it was this second desperate attempt that bore fruit. Against all odds, Avrumi didn’t die.

But the years that followed were grueling: Avrumi lay for months in the hospital, and then was in intense rehabilitation for years, learning to talk and walk and do the things boys his age could take for granted. The witty, learned young teenager had been thrust backward in developmental time, and no one could definitively determine what would be the outcome.

The sheva brachos are over and it’s nearly midnight as we walk toward the car. On the way we notice Avrumi standing unobtrusively to the side, clutching a small suitcase.

“Where do you need to go?” we ask him.

“No, no, it’s too far for you,” Avrumi demurs.

“Please let us, it’s our pleasure,” my husband persists.

“Okay, but only if it’s not out of your way,” Avrumi reluctantly agrees. “I need to get to Bayit Vegan.”

He climbs in the car and almost immediately draws us into friendly banter. Soon, the conversation turns to the accident. “I was on my way to a chavrusa with a friend,” he begins, “and right after I got off the bus and crossed the street, I realized I’d forgotten my phone on the bus.”

I imagine the 14-year-old Israeli boy at the cusp of decades of devoted Torah study, who has traveled a distance to learn with his chavrusa. The contrast between what was and what is clogs my throat with tears.

But Avrumi is upbeat, even jovial in the telling. “On my way back across to get my phone, I met up with a speeding vehicle. The meeting was decidedly unsuccessful,” he finishes jokingly. There isn’t a shred of self-pity in his tone or demeanor as he describes the outcome and its repercussions; his attitude conveys a mature undercurrent of acceptance.

Someone else picks up the thread of the conversation, when suddenly Avrumi, peering intently out the car window, cries out: “Wait! Wait! Where are we?”

He repeats the question, his tone resolute, insistent.

“This is the intersection of Golda Meir and Givat Moshe,” I answer, confused with the sudden urgency of his query.

But before I can even finish the words, Avrumi breaks in with a resounding: “Baruch atah Hashem Elokeinu Melech haolam she’asah li nes bamakom hazeh.”

Astonished, we answer in unison: “Amen!”

“I received a psak that I may say the brachah with Sheim u’malchus once every 30 days when I pass the site of the accident,” Avrumi explains matter-of-factly. “I’m not always in Yerushalayim, so I didn’t want to lose my chance.”

I wonder at this person who was once so whole, his life abruptly shattered and rerouted and ultimately rebuilt, with familiar contours resketched, expectations rewritten. A person for whom all the givens had to be reimagined, yet who refuses to live on the fringes of life, instead blessing his altered reality once every 30 days.

And I think perhaps, in him, I can begin to reimagine churban and nechamah as well.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 751)

Oops! We could not locate your form.