Heaven on a Hilltop

| November 18, 2025On a French hilltop, Rav Chaim Chaikin guaranteed Torah would rise again

Three unlikely Holocaust survivors — a French rav, a Polish scholar bereft of his entire family, and a talmid of the Chofetz Chaim — climbed a hilltop in the French resort town of Aix-les-Bains and declared that Torah would rise again. Eighty years later, talmidim remember Rav Chaim Yitzchok Chaikin, the humble giant who carried the flame across continents. This is the story of a yeshivah called “Aix,” and the man whose light still illuminates it

1945.

The German troops who’d occupied France for five years have finally gone, leaving behind a small and wounded Jewish community — those who managed to survive the roundups and deportations to the East. Now, in the resort village of Aix-les-Bains, a vacation destination for nobility and the wealthy in the east of France, a French rav joins up with a Polish scholar and sole survivor of his family, together with a talmid of the Chofetz Chaim who’d just spent five years in a German POW camp, in order to rebuild Torah in this devastated region.

They rent a 900-year-old mansion on a hilltop — the locals say the villa was Queen Victoria’s summer vacation home, and they also say it’s haunted by ghosts. But ghostly sounds don’t bother them — they will fill it with the sound of Torah.

A trickle of refugees from Eastern Europe arrives at the yeshivah. Soon, French teenagers join, and afterward, a constant stream of North African bochurim from Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco fill the shiur rooms. The mesivta, beis medrash, and kollel become the linchpins of Torah in France, as a Bais Yaakov seminary and community grows around them.

2025.

Thousands of talmidim gather in Paris to honor their yeshivah, a lighthouse of Torah in little Aix-les-Bains (pronounced “eks le bah”). It has cultivated over 6,000 talmidim to date, among them hundreds of rabbanim and dayanim leading communities across Eretz Yisrael, France, Morocco, and the United States.

This isn’t a fundraising appeal for this institution, known among French Jews simply as “Aix,” just the joy and emotion of reconnecting, inspired by the rousing words of Slabodka Rosh Yeshivah Rav Moshe Hillel Hirsch and the uplifting song of Motti Steinmetz. And above all, they’re all gathered to honor the memory of the tzaddik who built the yeshivah and who immeasurably impacted the religious lives of French Jewry, the legendary figure they carry in their hearts: Rav Chaim Yitzchok Chaikin. This is his — and their — story.

The very existence of a yeshivah in France in the first part of the 20th century was not a given at all. France was cultured and modern, far from the Eastern European centers of learning, but that didn’t hinder the vision of a great man named Rav Nosson (Ernest) Weill (1865-1947), chief rabbi of Colmar and the Upper Rhine, who wanted French Jewry to have a Torah base that would secure their future. The Jews of the Alsace region, where he was based, were the most traditional of their countrymen, but even for them, a yeshivah was somewhat of a forgotten concept.

Rav Weill opened the institution in 1933 in Neudorf, just outside Strasbourg on the French-German border. Rav Simcha Wasserman, oldest son of Rav Elchonon Wasserman Hy”d and a giant whose greatness was hidden by his outward simplicity, was sent by his father to head the yeshivah. But when Rav Elchonon instructed Rav Simcha to move on to America in 1938, another son, the gaon Rav Naftali Wasserman Hy”d, suggested that a certain talmid of Radin by the name of Rav Chaim Chaikin — who had been one of the Chofetz Chaim’s closest disciples and had stayed on in the yeshivah after the gadol’s passing — was suitable to take over as rosh yeshivah in France.

Through Our Rebbi

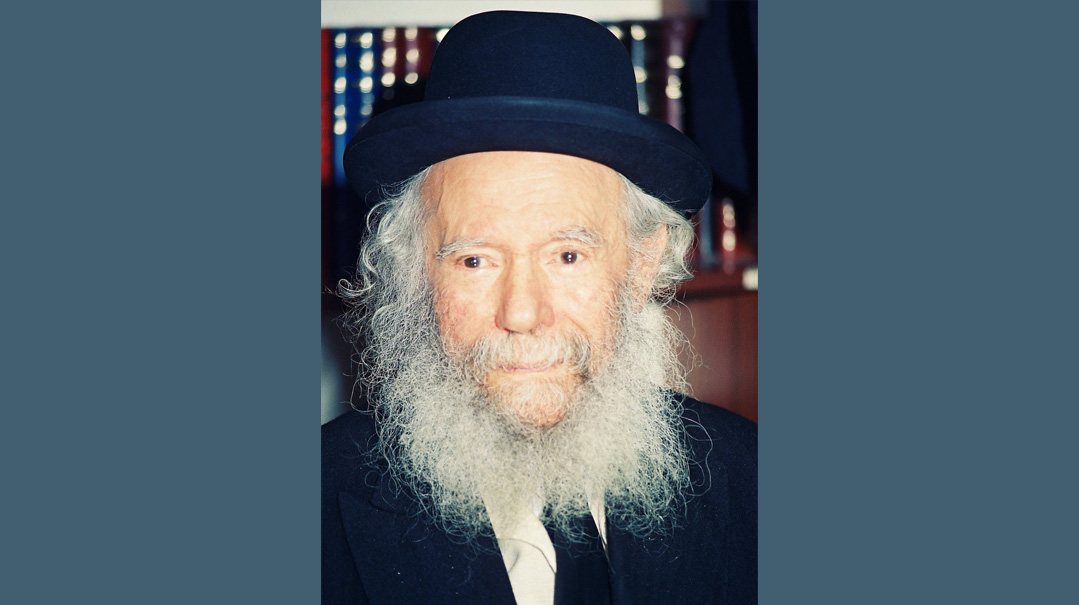

Rav Chaim Yitzchok Chaikin (the name Yitzchok was added in the 1980s during an illness) is still synonymous with the Aix-les-Bains yeshivah 32 years after his passing — the humble, self-effacing Torah giant who laid the groundwork for modern-day Torah learning in France.

He was born in Kossove in 1907, the town where Rav Shmaryahu Yosef Karelitz, the Chazon Ish’s father, was the rav. The Chaikins (they spell it Chajkin in France) lived next door to the Karelitzes, and during his childhood, young Chaim Yitzchok remembered the Rebbetzin sitting and talking with his mother every Shabbos afternoon. Later, he assumed that Rebbetzin Karelitz had probably encouraged his mother to send her sons to yeshivah.

When Rav Shmaryahu Yosef Karelitz passed away, the rabbanus of Kossove was assumed by both his son, Rav Itzele Karelitz, and his son-in-law, Rav Abba Savitsky. Rav Itzele became Chaim Yitzchok’s first rebbi muvhak, and Chaim Yitzchok benefitted from a close personal relationship as well. In fact, he remembered seeing, as a young boy, the letter the Chazon Ish wrote to his mother and brother to suggest the Steipler Gaon as a shidduch for his sister, Pesha Miriam.

When Chaim was just 17, the Chaikin children lost their father, Chaim.following in the footsteps of his older brother Mottel, then spent three years learning in Baranovich, which left an impression of seriousness and incredible hasmadah on his entire life. For Rosh Yeshivah Rav Elchonon Wasserman, Torah was an exclusive focus; even one minute of bittul Torah was significant.

When he was 20, Chaim decided that he wanted to go to Radin and learn from the Chofetz Chaim personally. It was in his blood from his own father. “My grandfather had been learning the seforim of the Chofetz Chaim and carrying them with him for years,” says Rav Chaikin’s son, Rav Naftali Chaikin, who is today a rosh kollel in Strasbourg and a popular lecturer.

However, the tzaddik was already aging by then, and so Chaim went to ask the mashgiach of Baranovich, Rav Yisroel Yaakov Lubchansky, if the Chofetz Chaim was already too old for him to learn from. The mashgiach knew the questioner well, and told him, “Someone who is a mevakeish can learn from the Chofetz Chaim.”

And so, before Rosh Hashanah 5687 (1926), Chaim Kossover, as he was known by the name of his hometown, traveled to Radin, where he would spend the next seven years as a talmid and a meshamesh of the Chofetz Chaim. A mevakeish he certainly was.

Over the decades, every talmid who learned in Aix-les-Bains noticed that Rav Chaikin constantly quoted the Chofetz Chaim. Rabbi Gad Bouskila, Rabbi of Congregation Netivot Yisrael in New York, remembers how “throughout the six years I had the privilege of having Rav Chaikin as rosh yeshivah, he always gave over the teaching of the Chofetz Chaim, so that they became ingrained in our hearts. I can hear them still every day. We saw the holiness of the past through our rebbi.”

For seven years, Rav Chaikin learned Torah and absorbed the greatness of his rebbi. At the end of 5693(1933), the light went out in Radin — the Chofetz Chaim was niftar — but Rav Chaikin stayed on in the yeshivah for another five years. At the end of 1938, he accepted the position of rosh yeshivah in Neudorf, although his arrival was at a most inopportune time.

Survive and Thrive

By the time Rav Chaikin, who was 31 and still unmarried, arrived in Neudorf, he found only one student there. This was 1938, there was already great unease among the Jews of France, especially in Strasbourg, which is on the German border, and in the interim, the students had started to flee.

Rav Chaikin, however, was not deterred. Even for his one talmid, he made sure the yeshivah ran on a strict schedule, with official times for shiur, for recess, for meals, and for rest — a model that would later serve his own talmidim who went out to start their own institutions. (This one talmid was Rabbi Aryeh Meyer of Bnei Brak, whose grandchild would later marry Rav Chaikin’s grandchild.)

A few more bochurim, mostly refugees, arrived when they heard about Rav Chaikin, but soon, with the start of World War II and the German invasion of France, yeshivah life — and any semblance of normal life — ground to a halt.

During this time, Rav Weill suggested a shidduch for Chaim Chaikin. His future rebbetzin, Fraidel Slobotzky, was from Frankfurt am Main, but her family had fled to France. She was 13 years younger than the Rosh Yeshivah, and from a different background, but Rav Chaikin came to appreciate the qualities of her Yekkishe home, and decided that, if she would be willing to accept his main condition — that they both be devoted to the yeshivah — the match was for him. She gladly did, but before they could marry, the war intervened, the Slobotzky family escaped Europe to South America, and Chaim Chaikin was drafted into the French military as a foreign resident.

“Back in Poland, when my father was twenty, he fasted for three days before his medical exam for the Polish draft, fainted in the medical officer’s examining room, and was released from Polish army service,” says Rav Naftali Chaikin, explaining that that although his father was already in his early 30s, World War II had begun, and as a Polish citizen, his father was to be drafted into the Polish legion of the French army, where he’d have to face the twin dangers of brutal Polish anti-Semitism and German guns.

“My father stayed up nights to say Tehillim, but he was taken anyway. Yet his biggest tzarah ended up being his yeshuah. His entire family, eight brothers and sisters with their children, were murdered by the Nazis in Poland. No one survived. Meanwhile my father was captured by the Germans but survived as a prisoner of war,” Rav Naftali relates.

Hashgachah had it that Rav Chaikin was ill when the Polish battalion set out, so he was pushed into a French battalion instead, which was far more tolerant of Jews. For five years as a prisoner of war, he endured deprivation, hard labor, and hunger (he traded cigarettes or treif meat rations for whatever fruits or vegetables were available), but although he lost a finger, his life was saved, and most times, the rote labor he was assigned to kept his head free to review the Torah stored within. There was also never a day that he missed laying the tefillin that he somehow managed to keep with him.

In 1945, as soon as the war ended and Rav Chaikin was released, he sent out two telegrams — he had survived and wanted to move forward. One was to Rav Ernest Weill: Could they restart the yeshivah? The other was to his kallah: Would she return to France and join him? Both answers were positive.

Sign of Life

Meanwhile, Rav Ernest Weill had returned to France from Switzerland, where he had escaped to and survived the war years, and was living in the resort town of Aix-les-Bains, near the French-Swiss border. There, he met Rav Moshe Yoel Leybel, a passionate rav from Warsaw who’d been a talmid of Chachmei Lublin. While his wife and little children perished in the Holocaust, he had jumped off a death train headed for Auschwitz and survived. Rav Leybel had connections to the Vaad Hatzalah and to Mrs. Recha Sternbuch, and helped secure funding for hostels in Aix-les-Bains where rescued Jewish children who had been hidden by gentiles during the Holocaust could recuperate. He dreamed of opening a yeshivah to nurture talmidei chachamim who would spread Torah to reignite the ashes of the Jewish world.

When Rav Weill received Rav Chaikin’s sign of life, he sent him a message to travel to Aix-les-Bains, where the dreams of Rav Leybel and his own fused into a yeshivah they would name Chachmei Tzorfas. The realtor who was showing them the deserted mansion on the hilltop of Montee de la Reine Victoria turned the key in the lock, then turned tail and fled from a house he believed was haunted. But Rav Weill and Rav Leybel danced in the entrance hallway. Not only was the estate cheap, it was actually an ideal site for a yeshivah — spacious, separate from the town, and surrounded by a healing panorama of serene natural beauty.

Rav Chaikin arrived in Aix-les-Bains still wearing his military uniform and a beret, and, eschewing any form of kavod, was simply known as “Mr. Chaikin” to the boys in this nascent yeshivah — refugee teenagers, most of whom had lost everything. Without sinking into his agony over the past, the yet-unknown fate of his family, and the Torah world of Eastern Europe, or the worry about his personal future, Rav Chaikin focused on the present. Hashgachah had brought him to Aix-les-Bains, and Torah has the only permanence and certainty in this world.

In 1946, his kallah arrived and the couple established their new home within the walls of the yeshivah.

In those early days, the bochurim would gather firewood in order to heat the rooms. In the winter, the old house was so cold that the negel vasser water would freeze over. Rav Chaikin would go from room to room waking up the boys for Shacharis, which began at 6:30 a.m. His simplicity was legendary. The Rosh Yeshivah ate with the boys at their table, and although they eventually began calling him “the Rav,” he never put on the garb of a rosh yeshivah, never wore a frock coat. Yet he was their undisputed authority.

Still in 1945, the yeshivah took a turn that would make history for the Jewish world. Rav Weill, who always learned Gemara with the Rif — the 11th-century Rav Yitzchak Alfasi of Fez, Morocco — decided that as Morocco was a French protectorate at that time, the yeshivah should invite students from Morocco.

He had no names and no addresses, but that wasn’t a deterrent. He decided to start with the Rif’s city of Fez, and simply addressed a letter to the chief rabbi of Fez, explaining that there was a new yeshivah in Aix-les-Bains inviting bochurim to learn.

The letter was received by Chief Rabbi Yedidya Monsonego of Fez, who read it with wonder. Moroccan Jewry was suffering spiritually from the schools under the Alliance, a secular Jewish organization that offered education with the agenda of secularizing the traditional Jews of North Africa. Rav Monsonego offered his own son Aharon the chance to travel to France, and that’s how the yeshivah of Aix-les-Bains received its first Sephardi bochur, a demographic that would eventually comprise the majority of the student body. (Rav Aharon Monsonego arrived in Yeshivas Chachmei Tzorfas/Aix-les-Bains in 1945 and didn’t return home for the next seven years, having become a talmid muvhak of Rav Chaikin. He was a great talmid chacham and educator who served as Chief Rabbi of Morocco for several decades until moving to Eretz Yisrael in 2014, where he passed away four years later.)

“The entire yeshivah went to the train station for his arrival, to see what a Moroccan Jew looked like,” Rav Naftali relates.

Over the next years, Aharon Monsonego was followed by thousands of talmidim from Casablanca, Meknes, Fez, and other towns. In 1962, when the French left Algeria, tens of thousands of Algerian Jews immigrated to France, and Algerian and Tunisian bochurim flocked to Aix-les-Bains.

“Eventually, the student body had a Sephardic majority, yet Rav Chaikin never budged from the nusach and the learning style he had received from his rebbeim,” says Rabbi Gad Bouskila, who was in the yeshivah from 1973 to 1978. “In my times, the student body was seventy percent Moroccan, twenty percent French, and ten percent children of the rebbeim, but we davened in nusach Ashkenaz every day.”

On Shabbos, however, the zemiros sung in the yeshivah dining room reflected the great diversity of its talmidim. (Rav Chaikin himself, from the Torah world of Lithuania, was not used to singing zemiros at the Shabbos seudah. When, at the Rebbetzin’s request, he began to add niggunim to the seudah, he originally sang the words of Mishnayos in a melody, to make his wife happy while at the same time avoiding what he considered bittul Torah. Later, he came to see the beauty of singing zemiros and added some to the Mishnayos.)

I Don’t Need Double

The yeshivah wasn’t only a place for war refugees or students from North Africa, though. Many larger-than-life personalities passed through its portals, leaving their mark and influence. During the early years, the “Telshe illuy” Rav Mordechai Pogromansky, who managed to survive the war in the Kovno ghetto, spent almost a year in Aix-les-Bains, sitting and learning in his room in the yeshivah and providing a living role model of a talmid chacham and mussar personality.

Rav Chaikin’s right-hand man for half a century, the one providing the “flour” for the Torah, was the indefatigable menahel, Rav Gershon Cahen. A rabbi in the Alsace region, he spent Monday to Wednesday in the yeshivah in Aix-les-Bains every other week, and worked to fundraise and finance the yeshivah without taking a salary for 50 years, supporting his family on his rabbi’s wage only, while influencing two generations of talmidim with his sichos and his dedication to their Torah. Later, he and Rav Chaikin became mechutanim.

Another personality who had a huge impact not only within the yeshivah walls but on the greater Aix-les-Bains community was Rav Eliyahu Elyovics. He was Hungarian, from a chassidic background, who joined the yeshivah as a maggid shiur in 1945 after spending the last years of the Holocaust as a POW in Germany. While he was attached to the yeshivah, he also taught the local children, and in the 1960s spearheaded building a shul and mikveh in the town — at the time the finest and most modern mikveh in all of France. This was his final labor of love for his people, because in 1968, even before the boros had filled with rainwater, Rav Elyovics collapsed in the classroom in middle of saying his shiur, and passed away from a major stroke.

After the war, many families were attracted to the peaceful community where Torah reigned supreme. Rabbi Elchonon Errera, a Manchester mechanech, relates how his parents, who were living in Paris, decided in 1952 that they wanted to move to a makom Torah.

“They wanted to live next to the yeshivah of Aix-les-Bains,” Rabbi Errera says. “Rav Chaikin, who lived frugally in a small apartment in the yeshivah with his family, decided that he would build a wooden cabin for my parents. He banged on the bimah and recruited bochurim to take up shovels and dig the foundations.”

Rabbi Ererra’s father, Rabbi Shmuel Ererra, was in fact a Parisian businessman who, in 1952, abandoned his career in order to study Torah with Rav Chaikin. Reb Shmuel later joined the yeshivah staff, while his wife ran the town’s elementary school. Until today, the Aix-les-Bains community has a different flavor and character than other French communities. Kehillah members are mainly involved in kollel and chinuch.

Dr. Robert (Moshe Yaacov) Goldschmidt, dean of Touro University in New York, learned in Aix-les-Bains for two years in the 1960s and still remembers cycling up the mountain to yeshivah with a heavy backpack loaded with milk flasks after having taken his turn to watch the milking for chalav Yisrael at a local farm.

“The yeshivah was a very warm place,” he relates. “It had a strong emphasis on mussar and building middos. We learned Chovos Halevavos as a learning seder, and I remember that before we traveled to a Catholic school to sit for our government exams, we received a lecture on conducting ourselves properly and creating a kiddush Hashem.”

In 1975, the yeshivah opened a kollel with 40 yungeleit. It was also common for teenagers from schools, yeshivos, and colleges across France to spend their summer breaks learning in Aix-les-Bains.

Rav Elyovic’s son, Rav Shulem Elyovics of Antwerp, Belgium, is active in the yeshivah’s affairs until today. He recalls the unparalleled integrity of the Rosh Yeshivah.

“I was in the yeshivah office in Aix-les-Bains one day, when Rav Chaikin entered. He had turned seventy, and his government pension had arrived. Not that he ever retired — he worked in the yeshivah until the last day of his life — but he had received his pension. He said to me, ‘Reb Shulem, from today you stop paying me my salary. I’m getting my pension, so I don’t need two salaries.’

“I protested. ‘But we paid money into the pension fund every month, and now they’re giving it to you. It’s yours.’

“ ‘I don’t need double,’ Rav Chaikin insisted. ‘I don’t want to take more from the yeshivah.’

“I tried to convince him. I told him he has children in kollel whom he can help out, but he just responded, ‘Shulem, mish dech nisht arein in mein gesheften [Don’t mix into my business].’

“I said okay, but the story wasn’t finished. At the end of the month, the Rosh Yeshivah came in with 300 francs. He explained that his pension was 300 francs more than his yeshivah salary, so he wanted to pay the yeshivah for his apartment — the Chaikin family lived in a small apartment in the yeshivah building. He had lived there free as part of his salary, but now, as he was getting extra money in his pension, he wanted to pay the yeshivah for it. This was what it meant to be a talmid of the Chofetz Chaim.”

Shake the Heavens

Although the chassidish dynasty of Pshevorsk, based in Antwerp, was not exactly Rav Chaikin’s litvish derech, the previous rebbes Reb Itzikel and Reb Yankele, zichronam livrachah, and today’s Reb Leibish, were all close to Rav Chaikin, sharing tremendous mutual respect and even participating in each other’s family simchahs. In the aftermath of the Holocaust, Reb Itzikel was based in Paris when he first came to the thermal spa resort of Aix-les-Bains for the sake of his health. Thereafter, the Rebbe and his family spent many summers in the yeshivah — the room he slept in is called “La chambre de Rav Itzikel” until today. Rav Eliyahu Elyovics served Reb Itzikel devotedly, and several bochurim became his staunch chassidim.

“What would we look like without Reb Itzikel?” Rav Chaikin once said to his son, acknowledging the impact of these tzaddikim on Aix-les-Bains.

One year, the Rebbe spent Simchas Torah in Aix-les-Bains. Rav Chaikin walked past the Rebbe’s beis medrash after the yeshivah had finished davening. Gazing at the obvious spiritual ecstasy, he said that at that moment he understood the secret of anti-Semitism: how a gentile observes a Yid’s happiness and meaningful life, and is filled with jealousy, pain and hatred at what he can’t have.

“But we are Jewish, and there is nothing holding us back from joining these chassidim and training ourselves to express such love for Hashem and his Torah,” Rav Chaikin averred. That day, the litvish rosh yeshivah and his talmidim joined the chassidim of Pshevorsk to dance and sing and shake the heavens.

“Many years later, in 1974, Reb Itzikel called my father to say he was coming to rest in Aix-les-Bains, and asked if he could again have the little room in the yeshivah. I watched my father take a broom and run to the room with delight to start sweeping it for the tzaddik,” says Rav Naftali Chaikin.

Rav Chaikin was thrilled that his talmidim had the opportunity to connect to a spiritual giant and see the Rebbe’s avodah, while his own primary vision was to create a network of talmidei chachamim who would move Yiddishkeit and limud haTorah forward all over France.

“My father learned Shulchan Aruch with some of his talmidim and tested them for heter hora’ah,” says Rav Naftali. “He arranged for some of the bochurim to learn shechitah. He sent many bochurim on to Slabodka Yeshiva in Eretz Yisrael when that was the best thing for them. But above all, he felt an achrayus to nurture talmidim who could teach Torah in France.”

The vision became reality. More than half of the rabbanim in France’s towns, cities and villages are Aix-les-Bains talmidim. Rav Yosef Chaim Sitruk, France’s chief rabbi from 1987 to 2008, said that Rav Chaikin was one of the biggest influences on his life, from the summers he spent in the yeshivah. Rav David Messas, chief rabbi of Paris from 1995 to 2011, was a talmid, and Rabbi Y.D. Frankfurter, rav of Khal Adas Yereim in Paris, is constantly quoting Rav Chaikin, whom he still considers his rebbi.

The yeshivah is still a bastion of Torah in France today, under the direction of Rav Tzvi Chaikin and Rosh Yeshivah Rav Yitzchok Weill, who arrived at the yeshivah in 1950, has been a maggid shiur for decades, and is rav of the town of Aix-les-Bains. He is considered today one of the senior roshei yeshivah of Europe.

Never Give Up

Rabbi Gad Bouskila had been in the yeshivah for four years when Rav Chaikin brought a certain boy to learn with him during the review seder. “It was a boy who knew nothing, who came from a distant French town and had never been to yeshivah before,” Rabbi Bouskila relates. “I tried it for a week, and then I told Rav Chaikin that I felt I was wasting my time. But he wouldn’t relent. He said, ‘No. Your mission is to teach him, and you’ll see that while you teach him, you’ll excel in your own learning.’ ”

None of the talmidim understood why this particular boy got so much love from Rav Chaikin, why he was invited to Rav Chaikin’s home to eat almost every Friday night, why the Rosh Yeshivah was taking special care of him.

Rabbi Bouskila eventually left to learn in Paris, then Lakewood. Four years after he arrived in America, he came back to France to visit his sister, with his wife and two children in tow.

“My sister told me she had a surprise, and she invited this boy over,” Rabbi Bouskila says. “But it wasn’t a nice surprise. He came with no kippah, made no brachah on the tea and cookies. I asked him what had happened. ‘You learned with the Rav, and the Rav loved you!’

“He replied that he had moved on to university, left Torah, Shabbat and kashrut behind, and was in fact living with a non-Jewish woman. It was terrible.”

Almost a decade later, Rabbi Bouskila visited the same city again for a family bar mitzvah, and he led the davening in the local kollel. At the kiddush, a bearded kollel man came over. “Don’t you recognize me?” he asked Rabbi Bouskila.

It was that boy.

“He took me to a corner and he told me what had happened,” Rabbi Bouskila relates. “He said that whenever he did an aveirah, he saw the face of the Rosh Yeshivah in front of him. ‘I saw his picture every Friday night, I saw him in front of me every time I entered a restaurant, every time I traveled on Shabbat,’ he told me. ‘I was haunted by him — he never left me alone. Eventually, I couldn’t live like that anymore, and I left that other life behind. In the end, I married a girl from the community and even joined the kollel. All my children are in Torah schools.’ Now I finally knew why the Rosh Yeshivah had given him so much love. It accompanied him to the hardest places, and it eventually saved him and his future.”

Alongside My Rebbi

“Our father told us many, many stories about the Chofetz Chaim, and about his own good friend, Nosson Brezher Hy”d, who was meshamesh the tzaddik,” says Rav Naftali Chaikin. “In all the stories, though, he never mentioned his own exceptional closeness.

“When we sat shivah for my father, an old man from Tel Aviv came to be menachem avel. He and my father had come to Radin to learn around the same time, and he told us that at that point, the Chofetz Chaim was too weak to walk to the yeshivah, so a ‘baal agoleh’ used to bring him. Sometimes, the wagon driver went out of town with his horse, leaving his wagon in town, and when that happened, two bochurim would then bring the Chofetz Chaim. One would sit in the seat of the baal agoleh, so that the Chofetz Chaim would not notice anything amiss, and the other would pull the wagon, as there was no horse. ‘Your father and Nosson Brezher used to do this,’ the man reminisced. ‘They were the shamoshim, and they never let anyone else take over the job.’ We were taken aback. We had heard of Nosson Brezher being the meshamesh, but in all the thousands of times we heard my father speak about the Chofetz Chaim, we never heard about his own role. That was his humility.”

At one point, Rav Chaikin traveled across the border to Switzerland to meet the Brisker Rav, who was vacationing there. They went for long walks together, and the Brisker Rav asked him to share his memories of the Chofetz Chaim, requesting as much detail as possible. Rav Chaikin commented afterward, “Today I became a millionaire. I’m like a man who thought that the diamond he had was worth $100,000. Then he meets an expert who informs him that the stone is actually worth a million. I always knew that I was carrying diamonds and pearls, but today, when I saw how much importance the Brisker Rav attached to my rebbi’s words and actions, I became a millionaire.”

Rav Chaikin admitted that at the time, although they knew their rebbi was a gadol, they didn’t appreciate the full depth of the Chofetz Chaim’s personal greatness.

“We didn’t know who he was when we learned by him,” Rav Chaikin said, “yet we saw that the gedolim were mevatel themselves to him.” Rav Elchonon Wasserman used to leave his own yeshivah during Elul and the Aseres Yemei Teshuvah to spend these exalted days with the Chofetz Chaim. While Rav Elchonon was there in Radin, he would give a shmuess to his own alumni who were there, Chaim Chaikin included. “He told us to make the most of the Chofetz Chaim. Because even then, the bochurim just didn’t know.”

They might not have known, but the influence was still all-pervasive. “When we were in Radin,” Rav Chaikin once said, “not only did we not speak lashon hara, we didn’t even think lashon hara.”

Although the Chofetz Chaim is most famous for his sefer on hilchos lashon hara, Rav Chaikin recalled that most of the Chofetz Chaim’s drashos were about the importance of limud haTorah. “But he would say that if you cook a good cholent in a dirty pot from last week’s cholent, the cholent will taste terrible. First, the mouth has to be clean.”

The Chofetz Chaim used to go to the yeshivah in Radin to speak to the bochurim, but when he became too weak for this, the bochurim would come to his house instead. Once, when Rav Chaikin was sent to call the bochurim, most of them didn’t come — they were unwilling to interrupt their learning.

The Chofetz Chaim asked, “A vu iz der oilem?”

Rav Chaikin very embarrassedly responded that they wanted to sit and learn.

The Chofetz Chaim responded, “Vos meinen zei, as eibig zei gein hobben der Chofetz Chaim [What do they think, that they’ll always have the Chofetz Chaim]?”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1087)

Oops! We could not locate your form.