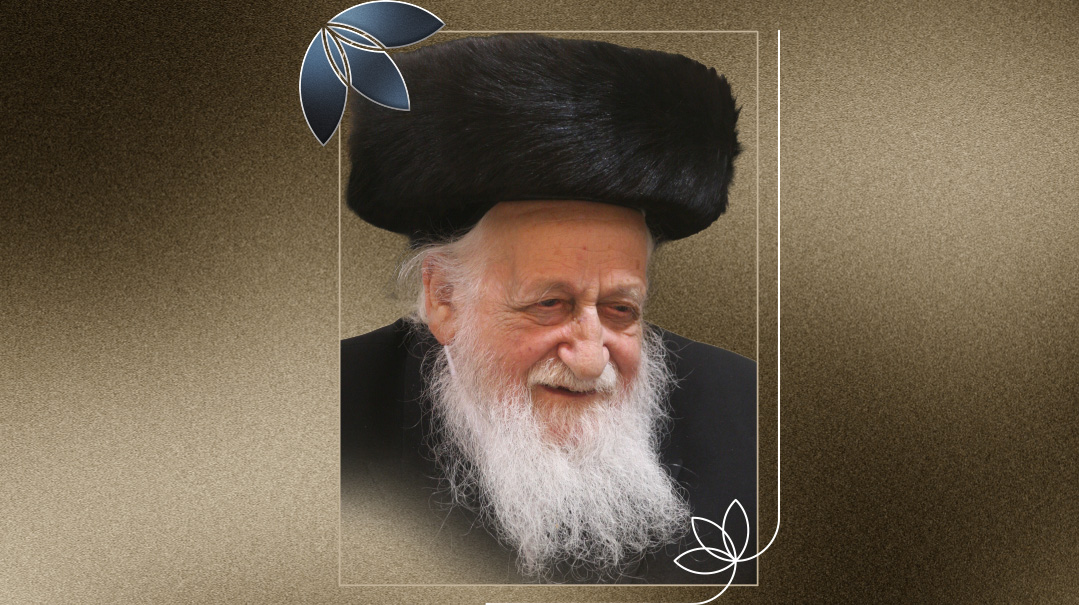

Heart of Love, Spine of Steel

Rav Elyakim Schlesinger branded generations with a century of love and leadership

Photos: Mattis Goldberg, Dudi Brown

The modest Stamford Hill home of Rav Elyakim Schlesinger, who passed away last week at the age of 104, was a citadel in the London suburbs. From behind that simple facade, the Rosh Yeshivah presided over a rare synthesis of Brisk, Hungarian fire, and Yerushalmi austerity, shaping generations with a century of love and a brand of leadership as uncompromising as it was misunderstood

To the uninformed, the modest yellow-brick home at the heart of Stamford Hill’s chassidish community was a typical North London house. But behind the front door that was never locked, 45 St. Kildas Road was far from ordinary.

Home to Rav Elyakim Schlesinger, the oldest rosh yeshivah in the world who passed away last week at age 104, it functioned as an embassy of sorts — an extraordinary outpost of Brisk and Yerushalmi-style avodas Hashem in London’s humdrum suburbs.

A legend in his own lifetime, Rav Elyakim was the meeting point of parallel worlds of greatness that together shaped him into a unique individual.

Born in Vienna in 1920 to Rav Dovid and Baila Schlesinger, his mother was a daughter of prewar Agudah leader Rav Yaakov Rosenheim. Despite that background and the fact that his wife, Rebbetzin Yehudit, was the daughter of Rabbi Moshe Blau, Agudah head in Eretz Yisrael, he trod a very different path that took him deep into the anti-Agudah world of Hungarian Orthodoxy.

After learning with his grandfather Rav Eliezer Lipshitz Schlesinger, descendant of Rav Elyakim Getzel Schlesinger who was the famed dayan of Hamburg, as a young teen he was sent by his father to Pressburg to learn under the Daas Sofer.

At a time when many traveled to Lithuania, that move was explained by proximity. Vienna is less than an hour by road to Pressburg, or Bratislava as it’s now known. But that initial exposure meant that the grandson of an Agudah legend was drawn into a different world that would put its stamp on him.

After Pressburg came Nitra, a yeshivah in the Oberland vein headed by Rav Shmuel Dovid Ungar. Then, when the Schlesinger family moved to Tel Aviv in 1931, Elyakim went to the Yerushalmi yeshivah of the Maharitz Dushinsky, the Hungarian-born Gaavad of the Eidah Hachareidis, whom Rav Elyakim came to consider as his primary rebbi.

Only after that deep immersion in the world of Hungarian-style yeshivos did a young Elyakim Schlesinger head to Lomza in Petach Tikva. As a chassan, he then went to Ponevezh, where he developed a close relationship with the mashgichim Rav Abba Grossbard and Rav Yechezkel Levenstein.

Eventually, his exposure to the litvish world led to a deep relationship with the Chazon Ish and then the Brisker Rav.

These great figures appreciated first and foremost that the young man was a masmid. As a bochur, he would keep his feet in cold water to prevent himself falling asleep as he learned deep into the night.

As a yungerman, he never slept more than two hours a night. He had a one-room apartment in Yerushalayim that was partitioned by a curtain. At 4 a.m., his chavrusa would arrive, and they would learn on the other side of the curtain from where the rebbetzin slept.

The Chazon Ish’s respect for the young man — whose daily learning often spanned 18 hours — was reflected in the term “yedid nafshi” that he used to inscribe a wedding gift. It was the Chazon Ish who urged his protégé to persist in his efforts to break into the Brisker Rav’s inner circle.

Taken together, these varying influences shaped Rav Elyakim Schlesinger as a leader who combined lamdanus, scrupulous adherence to halachah, and a willingness to take unpopular stances where others preferred to remain quiet.

But although Rav Elyakim wore the title of kannai proudly, in the public image that label acted — as it so often does in the wider world — to obscure his extraordinary qualities: as an educator, as someone overflowing with ahavas Yisrael, and as a talmid chacham.

first came to the fore as rosh yeshivah of Yeshivas Horomo — named after the Ksav Sofer — where he shaped generations of bochurim.

“He was there from the beginning of seder to the end, and on Shabbos afternoon in the summer, he could be seen learning for eight or nine hours straight,” says Rabbi Avrohom Veisfish, a talmid during the 1980s. “The most powerful lessons were those that he taught by example.”

On one memorable occasion, that involved a live display of ahavas haTorah when a distinguished guest visited, says Rabbi Michoel Scharf, who arrived as a bochur from France in the 1980s.

“Reb Yossel Ashkenazi, who was the famous gabbai of the Satmar Rav, walked into the beis medrash. Everyone stopped to see how the Rosh Yeshivah — who was very close to the Divrei Yoel — would receive him. But when Reb Yossel stopped a meter or two away from the Rosh Yeshivah, nothing happened. Rav Elyakim was so deeply involved in his learning that for a full 15 minutes, he didn’t notice that someone was standing right next to him.”

At the hanachas even hapinah for his yeshivah a half-century ago, Rav Elyakim set out his vision as a mechanech.

“The job of a doctor is to take a sick person and heal him, and the more ill that the patient is, the greater is the doctor who heals him. So too, a yeshivah is there to take struggling bochurim, and help them succeed — the more difficult the struggle, the greater the yeshivah.”

Yeshivas Horomo — which at its height was home to about 50 to 60 talmidim — followed that vision faithfully. It attracted the Brisker-oriented Schlesinger kehillah who were uniquely poised between the chassidic and litvish worlds. But it also served as a haven for many struggling bochurim from all over the world. In Rav Elyakim, they found a rosh yeshivah who functioned as a guide and father figure.

An outstanding talmid chacham who was a living link in the train of transmission for his varied rebbeim, he constantly thought of his students’ wellbeing — spiritual and material.

That could reach unusual lengths. On one occasion, the cook was late in unlocking the yeshivah kitchen for supper. As the minutes ticked by and no one came, an uproar broke out and the Rosh Yeshivah himself came to see what the trouble was.

When told of the obstacle, he responded simply: “The bochurim have to eat — so break down the door!”

When bystanders urged that surely such a drastic measure was unnecessary when the bochurim could simply wait a few more minutes, his response was firm: “No — then they’ll be late for seder, and now they need to eat.”

Against the Flow

It was the dreaded polio outbreak in Eretz Yisrael in the 1950s that first brought the Schlesingers to Europe. When a daughter was stricken with the disease, the family moved for a year to Switzerland, where the girl was treated in a sanatorium, and Rav Elyakim served as co-rosh yeshivah with Rav Yitzchok Dov Koppelman in Kapellen.

Ultimately the Schlesingers moved to London, where there was precious little purchase for Rav Elyakim’s purist devotion to Brisker truth. Widespread yeshivah study — never mind kollel — was a thing of the future. Even among Stamford Hill’s chareidi community, at the time there were few who would countenance the idea that secular studies were to be avoided.

Yet the newcomer persevered. Over the decades, he succeeded in turning his yeshivah into an outpost of Yerushalmi life — both in the aesthetics of shtreimel and rekel, and the upbeat atmosphere of learning.

Step one in that process was schooling, where he went against the grain and founded Tashbar, the country’s first kodesh-only school that proved to be a model for others.

Rav Elyakim’s brand of searing dedication to Torah and Brisker emphasis on eisek hamitzvos — all-consuming involvement in the practical aspects of mitzvos — found a home in Stamford Hill.

His kehillah became the first stop of arba minim suppliers, who knew that the Schlesingers were generous patrons. Rav Elyakim himself would buy many different types of esrogim to fulfill all halachic opinions.

In the same way, matzos meant supervising the process personally from beginning to end. The Rosh Yeshivah drew the mayim shelanu himself, and ground the wheat in his own office.

Erev Yom Kippur was the time when talmidim — past and present — gathered for a brachah from their rebbi. Dressed in his shtreimel and Yerushalmi kittel, he would dispense personal brachos in his office in a process that would take hours.

Then there were the heights of joy and depths of mourning of the year — all within the same four walls. “During the Nine Days, the Rosh Yeshivah did Tikkun Chatzos in the day and at night, and on Tishah B’Av, he would say kinnos with rivers of tears,” recalls Rabbi Veisfish. “Simchas Torah was a true Yerushalmi joy — talmidei chachamim tumbling on the floor in front of the sefer Torah to show their hisbatlus to the Torah.”

Rav Elyakim’s career in chinuch had begun back in Yerushalayim of the 1940s when he founded Yeshivas Pnei Moshe, named after his father-in-law Rabbi Moshe Blau. An early talmid there was the great Breslov mashpia Rav Yaakov Meir Shechter.

The secret to Rav Elyakim’s success was that at heart, he was an instinctive educator who knew how to coach the best from his talmidim at whatever level they were.

One wall in the beis medrash was dedicated to chiddushei Torah, which he encouraged even the youngest talmidim to write. Those who couldn’t were coached by older bochurim, or the rosh yeshivah himself.

Despite the vast gap in abilities and knowledge, it was the towering figure of Rav Elyakim who would learn with new bochurim to instill them with self-confidence.

In a country where the idea of summer camp as an educational tool has never really taken root, Rav Elyakim was an innovator. Relaxation before Elul was practically part of the yeshivah curriculum, and he insisted that every bochur attend the camp.

The Rosh Yeshivah’s singular approach to chinuch dictated that despite his own high yekkish standards — he was always first to Shacharis — he wouldn’t wake up his talmidim, saying that they needed the sleep.

“Don’t get in their way,” was his educational maxim of non-interference.

The devotion that the Rosh Yeshivah showed his talmidim was mirrored by their devotion to him. Last year, Rabbi Yanky Schlesinger asked his venerable grandfather about the unusual love that he displayed to children.

Despite the fact that his schedule was bursting, visiting kids would get time plus a candy and a brachah.

“Why do all children get such love?” the grandson asked.

“Because each one could be the next gadol hador,” he answered.

In Their Shadow

That attitude was based on his own interactions with gedolim of all types. Recollections from the Maharitz Dushinsky to Rav Zelig Reuven Bengis and the Chazon Ish and Brisker Rav are published in his sefer, Hador V’hatekufah.

One thing that he took from his rebbeim, says Rabbi Michoel Scharf, is the very fact that they were active teachers with disciples. “The Rosh Yeshivah would say that once upon a time you would ask a bochur where he learned, and he would say ‘by Reb Boruch Ber’ or ‘by Reb Elchonon.’ Now, you’ll hear ‘In Ponevezh, in Mir.’”

The difference, Rav Elyakim would explain, is that bochurim need to spend years with a rebbi, absorbing his Torah, his avodah and hashkafah. Without a rebbi — if you’re just part of an institution — you can’t grow.

“That’s how the Rosh Yeshivah was to us,” Rabbi Scharf concludes. “He was a mechanech, a tatteh — everything!”

Of all his influences, perhaps the school of thought that Rav Elyakim was most closely linked to was that of Brisk. It was the Brisker Rav who had advised him to move to London, and that advice came about after Rav Elyakim, as a young avreich, had formed an unusually close bond with the Rav.

On one occasion, Rav Elyakim, who, together with Rebbetzin Yehudit, had nine sons and a daughter, went to ask the Brisker Rav for a brachah for success in his children’s chinuch.

But the visitor was so overcome with tears that he could barely make himself understood. At that point, the Brisker Rav called in his sons to witness what was going on. “I want you to see what it means for someone to care about chinuch,” he said.

Another sign of that respect came via a shidduch suggestion that resulted in an unusual brachah.

The Brisker Rav had an older son who was unwell and never married, but as he got older, that situation delayed shidduchim for his younger son, Rav Dovid Soloveitchik.

There were many who were concerned, but no one dared to broach the subject — until Rav Elyakim plucked up the courage.

“What’s going to be with a shidduch for the Rav’s son?” he asked.

The Brisker Rav thanked him for his question, and then added something unusual. “You’re the only one who cares!” he said. He waved away his younger visitor’s explanation that others were too awestruck to approach him, saying that if they really cared, they would overcome the fear.

Out of gratitude, the Brisker Rav gave Rav Elyakim Schlesinger a brachah for arichus yamim — one that was clearly fulfilled.

you didn’t know otherwise, Rav Elyakim’s Kol Nidrei derashah was a fine introduction to his fiercely ideological view of hashkafah. On this holiest night of the year, he would speak with tremendous passion about Klal Yisrael, and regularly berate the rampant secularism and Zionism in his precious Eretz Yisrael.

In Rav Elyakim’s telling, his Satmar-like stringency that rejected participation in the Israeli political process and saw Agudah as hopelessly compromised, was something that he’d heard from the Chazon Ish himself.

That viewpoint — disputed by the Chazon Ish’s talmidim — was controversial, given that the litvish mainstream sees the Chazon Ish as the father of a pragmatic engagement with Israeli politics.

London’s preeminent rosh yeshivah wasn’t afraid of the title kannai.

“In Megillas Esther, Mordechai was a kannai, so why is he called ‘ish Yehudi’ and not ‘ish kannai’?” he asked.

“Because to be a kannai,” he would explain, “to stand up for kevod Shamayim when you see that something is wrong, is by definition to be a Yid!” he would say.

Despite his fearlessness, Rav Elyakim knew the title came at a cost — one that he was all too well aware of, as is clear from his writings.

Like his rebbi the Chazon Ish, Rav Elyakim had a notably poetic pen, and in one poem from Purim 1965, he wrote in searing terms about his lonely path of truth.

“Open rebuke that comes from hidden love is judged as politics/ and against all who don’t follow the accepted line, a holy war is declared/ the swindler is considered clever and the deceiver is held to be wise/ to lie for the sake of peace — in this mitzvah, they’re very stringent.”

Far from being a mindless machmir or reflexive zealot, many of his writings show the profound depth of love for Hashem that was the engine of his stringent approach.

In Shir Emunah, a poem in Yiddish that his talmidim printed in a Haggadah, he begins:

“To You, Hashem Yisbarach — Gottenyu, to You/ my soul, my entire being goes out/ How Great are You, O Creator, how High and Holy are You/ it longs for you, O Hashem, the soul that you gave to me.”

Standing up for the truth meant first and foremost adherence to mesorah and the insistence that any change to what gedolei Yisrael had permitted was inherently suspicious.

One of the Rosh Yeshivah’s campaigns, says Rabbi Avrohom Veisfish, who is a shochet, was against government interference in shechitah.

Even when other rabbanim thought it inadvisable to challenge the authorities’ ban on the universal practice of turning a cow upside down for shechitah, Rav Elyakim tried to combat the new rules.

“You’ll lose the election if you act against religious practice,” was the message that he conveyed to Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

The same fundamental opposition to innovation in Jewish life was behind his rejection of computer-checked safrus. While others adopted the technology, he insisted on rigorous checks by sofrim alone.

Over the last decade, as education authorities sought to impose increasingly problematic teaching requirements on all schools, the frum community leadership attempted to find ways to avert the legislation.

But departing from the low-key approach adopted by chareidi community organizations, he spoke out strongly. In 2019 — at 99 years old — he left the confines of Stamford Hill to attend a meeting in Parliament on the subject.

His campaign continued as authorities turned their attention for the first time to regulating yeshivos. He did not believe, the Rosh Yeshivah wrote to the lawmaker who had championed the move, that “it is the desire of Her Majesty’s Government to go down in history as the first democratic nation where Jews are being restricted in practicing their religion freely.”

Unafraid of ruffling non-Orthodox feathers, when necessary, he continued: “Unfortunately, not all Jews live their lives as dictated to us by the Almighty. I do not wish to speak about their approach, which stems from the desire to assimilate Jewish values with a liberal lifestyle.

“Orthodox Jewry, on the other hand, is determined not to deviate in the slightest way from the way of life passed down to us by our ancestors, and our goal in life is to pass this down to future generations.”

But crucially, what set this approach apart from the destructive zealotry that Rav Elyakim condemned was how he treated those with whom he disagreed.

In one case, a rosh yeshivah of a very different hashkafic background came knocking on the door to collect. A grandson went to the front door and handed him a small donation. But when his grandfather heard, he was shocked.

“It’s not kavod haTorah for a rosh yeshivah to be collecting 50 pence and a pound,” he exclaimed.

Despite his age, he ran into the street to find the visitor, and personally took the rosh yeshivah around the local gvirim to help him collect.

The respect for truth-seekers went beyond those who were Jewish.

Responding to a non-Jewish woman who had shared her religious dilemmas, he wrote how impressed he was “with your deep religious feelings and true trust of the Al-mighty G-d of the universe.”

In a postscript, the Rosh Yeshivah then went on to correct her mistaken reading of the Bible, the surface meaning of which implies that King Solomon was an idolator. In an example of the combination of respect yet firmness with which he interacted with those far from his own path, Rav Elyakim then went on to share the true meaning as explained by “our Sages.”

Grounded Approach

That unceasing guard duty atop the watchtower of Jewish life stemmed from reverence for the past — and that led to Rav Elyakim’s lifelong involvement in safeguarding kevarim.

For decades, he acted to preserve batei olam in Europe that were threatened by local authorities. Such was his commitment to the issue over the years, that when he dreamed on Rosh Hashanah night that he’d been greeted by hundreds of people that he couldn’t identify, Rav Elyakim presumed that they were the souls of those whose graves he had rescued.

Rabbi Yitzchak Shapira, who heads the European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative that preserves and restores batei olam across Europe, had extensive contact with the Rosh Yeshivah over the issue.

It was Rav Shmuel Wosner who told Rabbi Shapira about Rav Elyakim Schlesinger, his childhood friend from Vienna. “He’s a tremendous expert on the halachos of batei olam,” the posek said.

That introduction secured the halachic input of Rav Elyakim in 2014, and the next year he spoke at a gathering in Berlin where the German government had come on board as a major financial backer of the effort to renovate Jewish cemeteries across central and Eastern Europe.

“I’ll never forget Rabbi Schlesinger’s speech to the high-level meeting,” says Rabbi Shapira. “He spoke in German, and read out Tehillim (129): ‘Al gabi chorshu chorshim, he’erichu l’maanisam’ — on my back they plowed and extended their furrows.’ He used that as a reference to those who had plowed over the Jewish cemeteries on the back of those buried there.”

“The Rosh Yeshivah’s speech made a tremendous impression on the officials who were there,” says Rabbi Shapira. “Everyone was moved.”

he advanced in age, and continued to learn, teach, and speak out on major issues, London’s foremost rosh yeshivah became a legendary connection to long-vanished gedolim.

His longevity wasn’t simply a matter of long life — it was his vitality and force until his final days. Well into his 90s, he responded to the needs of a new generation by reopening his yeshivah — which had in later years become a kollel only — as a yeshivah ketanah and gedolah.

To everyone who was close to him, it wasn’t his clarity of mind at over a century old that stood out, so much as the thirst for Torah that had taken him so far.

Two months before his passing, a weak Rav Elyakim spoke and with great effort to a grandson about the miracle of Torah.

“It’s such a neis that we are able to learn Torah that we should have a Yom Tov just to say thank you!” he said.

Just ten days before his passing, Rav Elyakim’s essence as a teacher of Torah was on full display as he encouraged one more struggling bochur. The 15-year-old had been thrown out of his yeshivah, and so he went to the city’s veteran rosh yeshivah for help.

“I’m trying to learn with chavrusas, but it’s hard,” the boy admitted.

Taking the bochur’s hand with his own weak grasp, the 104-year-old gadol declared that he had an ally: “Mir vellen zich mechazek zein — we will strengthen ourselves together!” That lifelong chain of learning and teaching found expression in his tzavaah — one of many that he’d written since the late 1940s — which summed up what had driven an extraordinary life that bestrode so many worlds.

“Let no one say that I was a tzaddik or yerei Shamayim, because I know my shortcomings in these areas,” Rav Elyakim wrote. “But let them emphasize the toil in Torah, love of Torah, and love of each member of Klal Yisrael. And as much as they will speak about these, let no one worry — because they were the goals of my life.”

Zealous for Hashem

By Aryeh Ehrlich and Yisrael A. Groweiss

Two years ago, in honor of Rav Elyakim Schlesinger’s 102nd birthday, we wanted to hear firsthand memories about pivotal conversations that shaped history, from the last remaining link to legendary gedolim of yesteryear

The first clue that we were about to be transported from London’s Stanford Hill to the alleyways of Meah Shearim was the old, faded “Schlesinger” sign on the door.

As the door opened and we stepped inside, we could almost hear the echoes of a historic debate taking place over the next campaign on behalf of the sanctity of Klal Yisrael, or whether or not to hold a meeting with Ben-Gurion. And Rav Schlesinger, still clear as a whistle and incisive as ever, didn’t disappoint.

In a wide-ranging conversation, he shared memories of wartime Eretz Yisrael, of long-gone Zionist controversies, and he spoke of why the Chazon Ish is mistakenly seen as a proponent of participation in the Israeli political process.

Despite his vocal anti-Zionist zealotry, his love of every Jew was legendary, as was his love of Eretz Yisrael. He told us how he longed for Yerushalayim, “for a simple weekday Minchah there,” he said.

Fateful Journey

Reb Elyakim Schlesinger was almost 18 when World War II broke out. Five years later, in 1944, while the war still raged, he became engaged to Yehudis, daughter of Rav Moshe Blau. For a brief period, he was supported by his father-in-law, but two years later, in 1946, tragedy struck.

According to official reports, Rav Moshe Blau was heading an Agudah delegation to the US in the spring of 1946, when he contracted peritonitis aboard a Romanian vessel. He was taken off the ship at Messina, Italy, where, according to the commonly accepted account, he passed away in an Italian hospital, and was brought back to Eretz Yisrael for burial on Har Hazeisim. In Jerusalem of those years, the sudden passing was attributed to the heartbreak Rav Blau suffered following the painful split between the Eidah Hachareidis, from which he had been compelled to withdraw, and Agudah, which he continued to lead.

Rav Schlesinger told us he never bought that version.

“I still believe my father-in-law was the victim of a mysterious poisoning,” Rav Schlesinger asserted, although that suspicion, widely held in some circles, has never been corroborated. “This was two years before the founding of the state, and the British, who were responsible for maintaining order in the land, were debating whether to allow the establishment of a state. There were heimishe Yidden who told the British that the chareidim did not want a state, and so it was decided that a delegation of rabbanim would travel to England to discuss the matter with the authorities. My father-in-law was one of them.

“But before he departed, he showed me warnings he had received, saying that if he went, there would be consequences. He didn’t know whether to go or not. Then his mother told him: ‘If this is for the sake of Klal Yisrael, then you must go.’ What is clear is that when he was on the ship, he suddenly passed away under mysterious circumstances, allegedly from some rare intestinal complication. I tell you — he was poisoned.

“But there was also a great miracle in the tragedy. The sailors were waiting for him to die, and then they would throw the deceased into the sea and continue on. But all the passengers protested, so they stopped the ship in Italy, and Rabbi Meir Karelitz — the brother of the Chazon Ish, who was part of the delegation — and another passenger named Mrs. Ayala Rotenberg took him to the hospital in Messina, where he passed away a few days later.

“There were no Jews in that city, but then a Yid arrived at the hospital and asked, ‘Where is the rabbi?’ According to this man, his rebbe appeared to him in a dream and said there was a great rabbi at the hospital in Messina. After the petirah, this fellow made all the arrangements.”

After his father-in-law’s passing, Rav Elyakim Schlesinger would go on to chart his own path vis-à-vis the new state. Surprisingly, he contended that the Chazon Ish was against voting in Israeli elections — a position based on his own conversations with the gadol.

That was surprising, considering that we’d always heard that the Chazon Ish called for people to participate in elections, as did many of the gedolim of the time.

“Well,” the Rav said, “after the war in 1948, there were posters hanging in Yerushalayim with the Chazon Ish’s signature, claiming he was instructing people to vote. I came to the Chazon Ish with one of those posters and asked him what happened. He laughed and said, ‘You see that what they say in my name is not true?’ I told him he should issue a denial. He replied, ‘If so, I would have to deny something else every day.’ ”

Still, we asked, the Chazon Ish laid the foundation for the existence of the chareidi parties, and also received Ben-Gurion for a visit in his home.

“The Chazon Ish had to save Eretz Yisrael,” the Rav related, “and regarding that famous visit, there was a whole story there. By the way, Ben-Gurion also wanted to visit the Brisker Rav, who refused to receive him. The Brisker Rav, who was younger than the Chazon Ish, asked Rav Bengis, who was head of the Eidah Hachareidis beis din in Jerusalem, to write to the Chazon Ish instructing him not to receive Ben-Gurion. They searched for a messenger to deliver the letter. I was around, but the Brisker Rav didn’t want to send me, because I was a talmid of the Chazon Ish, and it wouldn’t have been proper for me to bring him such a letter.

“Instead, he asked Rav Yisrael Grossman, who was my chavrusa then, to bring the letter to Bnei Brak. But in the end, the Chazon Ish did it his own way. He believed that, for the benefit of chareidi Jewry, he should, in fact, receive the prime minister.”

According to Rav Schlesinger, the prime minister even came to the home of the Brisker Rav. “I was in the house at the time. I told the Brisker Rav that Ben-Gurion had arrived, and the Brisker Rav shouted, ‘Ich vil im nisht zehn! — I don’t want to see him!’ ”

In contrast to the meeting with Ben-Gurion, which the Chazon Ish insisted upon in order to try to regulate relations between the chareidi community and the state, Rav Elyakim related that for the cornerstone ceremony for Yeshivas Ponevezh, the Chazon Ish opposed inviting Yitzchak Ben-Zvi, the country’s president, who was basically a Zionist figurehead and not a power-player.

“There was a certain young man who heard about the Chazon Ish’s opposition, so he took matters into his own hands and had the electricity cut in the middle of the celebration in order to disrupt the visit,” Rav Schlesinger related with a wink. “The police searched for him but never found him. That’s because I hid him in my home for several days.”

Rav Schlesinger’s father-in-law, however, worked extensively to regulate relations between the chareidi community and the emerging state, although Rav Schlesinger had a bit of a different take on it.

“I will tell you what my father-in-law did,” he told us. “It was some time before the declaration of the state. A call came from Ben-Gurion’s office to my father-in-law’s home. I answered the phone. They said they wanted to speak with Rabbi Blau, so I handed him the receiver. A short conversation took place, and then my father-in-law told me he was going to a meeting with Ben-Gurion. I asked him, ‘Why are you going?’

“He didn’t answer the question, just told me, ‘Order a taxi and bring me a Sefer Bereishis.’ Apparently, Ben-Gurion wanted to open a war with the British, and his office staff, seeing it was impossible to calm him down, thought that my father-in-law could succeed, so they called him to come.

“An hour later my father-in-law returned and told me he had succeeded. He’d read him the opening pesukim of Bereishis together with the first Rashi, explaining that Hashem is in charge of Eretz Yisrael and when He deems the time right, He will give it back to the Jews. And then my father-in-law walked back home on foot, because he had no money for another cab.”

Rav Schlesinger might have been an ardent anti-Zionist zealot in his hashkafah, although he loved Yidden and loved Eretz Yisrael, and was equally as vocal in condemning any anti-Zionist campaign that turned violent or endangered the lives of Jews. And that same focused zealotry was what make him “zealous for Hashem,” able to remain hyper-focused on learning Torah around the clock, even as he reached his own centennial.

In fact, in 1942, when Germany’s General Erwin Rommel declared that he would overrun Jerusalem on his march through North Africa, there was tremendous fear throughout the Yishuv. The rabbanim declared fasts and prayer vigils, but Rav Schlesinger admitted that he was so immersed in his learning that he didn’t even realize the country was in jeopardy.

“I was then in Yeshivas Lomza in Petach Tikvah and had no idea that Rommel was practically at our doorstep,” he said. “Salvation came when Rommel suffered defeat at the Battle of El Alamein. The next day, as I sat in the shmuess of the mashgiach, I still didn’t know what had happened. The mashgiach was extremely emotional and kept repeating that there had been great miracles of salvation, but I was clueless.

“After the shmuess, I asked some bochurim what had happened, and they said: ‘We saw that you and your chavrusa were totally immersed in your learning, and so we didn’t want to disturb you and tell you that Rommel was defeated.”

Otherworldly Help

Rav Schlesinger’s connection to the Chazon Ish continued even after the gadol ascended to the Olam HaEmes. Rav Schlesinger felt strongly when he was working to preserve Jewish cemeteries throughout Europe, even when location of ancient graves seemed impossible to find. He received assistance that could only have come from the Next World.

The first instance occurred several years after the passing of the Chazon Ish. “He came to me in a dream and told me that in a certain city there had been a yeshivah where Jews were killed, and now they wanted to disturb the cemetery,” Rav Schlesinger recounted. “We traveled there and excavated, and exactly as the Chazon Ish had told me in the dream, I found Jewish graves. The chevra kaddisha of Antwerp removed the coffins and reburied them properly.”

And that wasn’t the only dream. The Rav told us how the Chazon Ish once came in a dream to a certain person who was trying to thwart their rescue efforts, admonishing him to leave the Rav and his team alone. The person himself, frightened and overwhelmed, told this to Rav Schlesinger.

For Rav Shlesinger, though, it was more than just a tzaddik coming to him in a dream. He seemed to have a certain “sense” when it came to locating and restoring graves.

“Baruch Hashem,” he said, “wherever we go, there is siyata d’Shmaya way beyond the natural order. I’ve been in many situations when we’ve come to a certain location and found a person who could tell us exactly where the graves stood. Later, that person mysteriously disappeared.”

He said that that’s what happened when they saved the grave of Rav Akiva Eiger in Poznań. “A few residential buildings had already been built on part of the cemetery, and another part was to be the site of an exhibition center,” he told us. “We arrived at a certain spot, and I felt it was holy ground. We told the local authorities not to build there. Later, we returned to the same place, and I felt the same thing. Then an elderly gentile woman approached and said that the entire area used to be a Jewish cemetery.

“We spoke with the company managing the buildings, informing them that the entire lot contained graves. The manager said they needed to ask the residents. We sat with the residents, and the building maintenance manager supported our position that beneath the ground was a Jewish cemetery. And somehow, all the residents agreed to do everything to preserve the sanctity of the place.

“It was a large area. With us was an elderly descendant of Rav Akiva Eiger, who remembered visiting the grave. We took measurements until we roughly identified the location. Then I opened a Chumash, and the pasuk that appeared before me guided me a few meters further down. Later, we discovered an old photo that confirmed our hypothesis exactly.”

Rav Schlesinger, of course, would not reveal the pasuk. It was part of his secret arsenal.

“It was part of the miracles we’re constantly seeing,” he said, “And you know, whenever we encounter difficulties, I go to Rav Akiva Eiger’s grave to ask for mercy, and the matter is always resolved.”

He told us that at this point, non-Jews across Europe understand the importance of preserving cemeteries, and help comes from all over. He told us about the ancient cemetery in Regensburg, today in Germany, the city of the Baalei Tosafos, where Rabbi Shapira’s ESFJ spearheaded an effort to restore the 800-year-old Jewish cemetery.

“When we brought it up to the non-Jewish residents there, they didn’t understand what it was about at all. They thought we were crazy,” he told us. “Today, however, there is a law passed in the European Union parliament that each country is responsible for preserving the Jewish cemeteries within its territory.”

Perhaps Rav Schlesinger merited such a long, full life because he was so devoted to the eternal lives of previous generations. He just shrugged, but he did admit that he was part of a cadre of those “who know the value of the graves of our ancestors. Who live the faith of the soul’s permanence and appreciate the merit of the souls of our forebears. Who understand the responsibility of the living toward those already in the Next World.

“In every generation,” he continued, “there are those who merit to live, and it’s their duty to care for the Jews who came before them, so that their rest not be disturbed. The thing is, I’m not sure how many people today actually feel this.”

He didn’t give a recipe for longevity, but he did give a tip that he said might help: “Don’t change from the way of the forefathers. Walk in their path. And of course, everything depends on Heavenly assistance. All my life, I fought so that nothing should be altered from the ways of our fathers. But why I merited so many years? I don’t know, and I don’t concern myself with it. The main thing is that we merit to live, however long, with pure hearts and pure thoughts.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1099)

Oops! We could not locate your form.