Hear the Music

Rav Meir Tzvi Bergman travels across the ocean to celebrate those who learn and live Torah

Photos Mattis Goldberg

In Yerushalayim, lineage means a great deal.

The families of Meah Shearim glory in the great deeds of ancestors they’ve never seen; the clever women choosing tomatoes in the shuk near the Yeshuas Yaakov Shul can identify familial traits that run back generations in a child just two years old.

And in that city of distinction, the Jerusalem of a century ago, the Bergmans were aristocracy. Residents of the Old City for seven generations, they were eineklach of Rav Avrohom Shag-Zwebner, the talmid of the Chasam Sofer who left his position as Rav of Kobersdorf to ascend to Yerushalayim, prompting his devoted talmid Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld to follow. They were eineklach of Rav Eliezer Bergman, one of the earliest builders of the Holy City. The Kollel Ho”d (Holland and Deutschland, whose immigrants the kollel would serve), which he established in 1838, built housing and raised significant sums for the Jews of the city.

Along with the rich lineage, there was something else. With the unique candor of the people of that city, my Yerushalayim-born grandmother, may she be well, recalls her cousins, the Bergmans: Aside from the scholarship and distinction, “Zei zennen gevehn hoicheh uhn sheineh” (they were tall and good-looking).

Rav Moshe Bergman was a familiar figure in the alleys of the Altshtot, the Old City, a respected member of the Perushim community, but also welcome in the courts of the chassidim as a great admirer of the tzaddik Rav Shloim’ke of Zvehil.

Along with his deep roots in the Holy City, Reb Moshe, who was versed in Kabbalah as well as the revealed Torah, also felt the pull of Meron. He often undertook the then-exhausting trip north to the mountaintop of Rabi Shimon, where he would delve into the inner dimension of Torah and fill his spiritual reserves.

He would need those reserves when he faced tragedy, not once, but twice.

On Erev Rosh Hashanah of 1934, the family was leaving Kever Rachel when an Arab driver tore down the narrow road, striking and killing four-year-old Nochum Bergman, as his parents and brother Meir Tzvi watched in horror.

Sometime later, typhus swept through Yerushalayim and Reb Moshe lost his young wife, Alta Liba Reizel, leaving him with just seven-year-old Meir Tzvi — his family of four having been reduced by half.

The great men of the Etz Chaim Yeshiva, where Meir Tzvi was a student, understood the risks that the tragedy posed for the gifted child. A few years later, they suggested that Meir Tzvi be sent to a real yeshivah ketanah, where he’d be exposed to talmidei chachamim who could broaden his horizons.

(During my conversation with the Rosh Yeshivah this week, he mentioned that period of his life and reflected, “I don’t have much to share about this, because only a yasom can understand what it means to be a yasom, Rachamana litzlan. To one who is fortunate enough to have parents, there is no point in trying to explain it.”)

Rav Meir Tzvi Bergman had a painful start, but he soon became a crown upon the family’s Yerushalmi aristocracy. At Rav Meir Tzvi’s wedding to the daughter of Rav Shach: (From left) Lomza Rosh Yeshivah Rav Reuven Katz, the chassan, Rav Shach, and Rav Chatzkel Levenstein.

You Will Sleep Here

At the age of 11, Meir Tzvi Bergman was sent to a hot, dusty town called Bnei Brak — really just an orchard with some huts and empty fields with only Torah and just Torah as its product. There the Yerushalmi child joined Rav Michel Yehuda Lefkowitz’s Yeshivas Tiferes Tziyon and was welcomed to the world of “litvisher lomdus.”

The yeshivah had no dormitory, so accommodations were arranged in a small hut used by the fruit-packers of Givat Rokeach during the day, but empty at night.

The days were filled with Torah, but the nights were hard. In the winter, the rickety hut was freezing and in the summer, the air inside was heavy and thick. Jackals howled in the distance, and the young orphan, longing for a mother, for a home, had trouble sleeping.

Barely bar mitzvah, the boy — like many of the budding scholars of the era — benefitted from the encouragement of the Chazon Ish, who would speak to him in learning.

One day, the Chazon Ish asked him an unexpected question. “Meir, where do you sleep at night?”

“I have a place, baruch Hashem,” the boy replied.

The Chazon Ish understood. “From now on,” he said, “you will sleep here.”

Meir Tzvi had a home once again. And the Chazon Ish treated the boy not as a guest, but as a son. “He farhered me,” recalls the Rosh Yeshivah now, “not asking me questions, and not wanting to hear my chiddushim. Rather, he wanted to me to go through the shakla v’tarya, questions and answers of the Gemara, Rashi and Tosafos, again and again.”

The boy was exhausted when he came home at night, but the Chazon Ish did not urge him into bed. The Chazon Ish himself would toil in learning until sleep overtook him, and he wanted to invest the boy with this same discipline.

As much as the Yerushalmer bochur was seen as family in that home, he also wasn’t. A close member of the Chazon Ish’s inner circle made a bris in the Chazon Ish’s home, following the daily minyan at haneitz. Meir Tzvi was at the bris, of course, and the Chazon Ish looked at him in surprise.

“Your place is not at events, but in yeshivah,” he said, ushering the boy out.

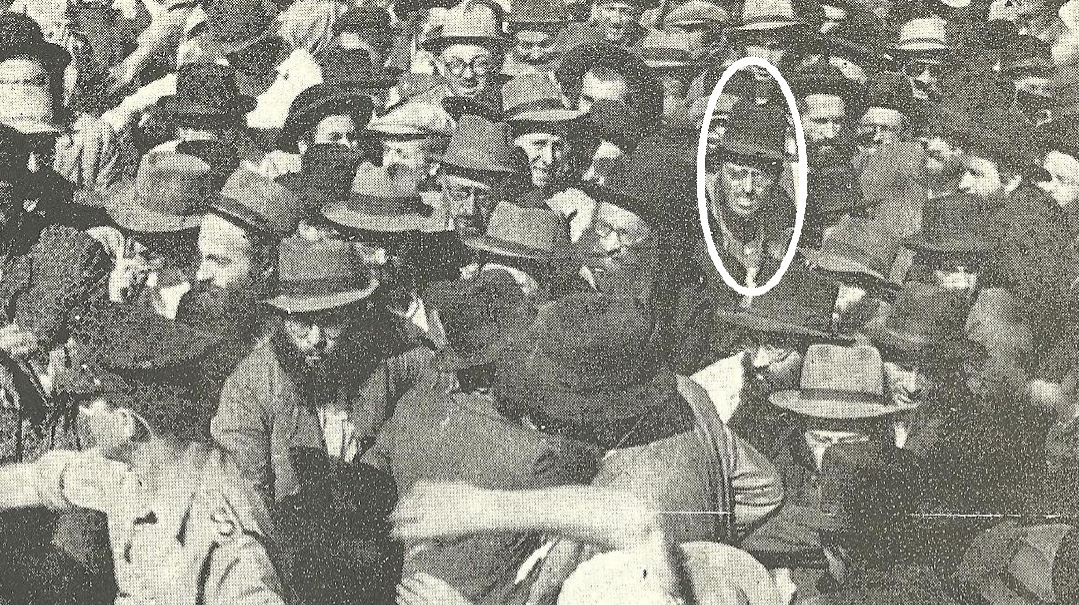

Carrying the mitah of the Chazon Ish

There was a message in the comment. The house was not a “chatzer,” its people were not affiliated with a party, and there were no social events: There was just Torah.

Until this day, these two lessons live on, evident to anyone who observes the conduct of Rav Meir Tzvi Bergman, Rosh Yeshivas Rashbi.

His schedule is largely based on learning, writing, toiling, his singsong filling his small Bnei Brak apartment until sleep overtakes him, and then, when it does, it doesn’t last long. He is back at the table well before dawn, singing the same song.

Though he is a member of the Moetzes Gedolei Torah, he is not much for events and formal appearances; his schedule focuses on writing and learning. The high point of the week is the intense shiur he delivers to the two hundred members of his kollel, many of them accomplished mechabrei seforim.

Just as the Chazon Ish told him.

One Yom Tov, Meir Tzvi accompanied his father on a visit to the tzaddik, Rav Shloim’ke. When the Rebbe of Zvehil heard where the bochur slept, he asked that Meir Tzvi serve as his shaliach to send a message about a halachic query regarding the Chazon Ish’s position on the International Dateline in Japan.

Rav Bergman still recalls the mission. “Rav Shloim’ke was known as a tzaddik, a Yid who was po’el yeshuos, achieving salvation for others when he went to the mikveh. People would ask him difficult questions, and when he emerged from the mikveh, he had clear answers for each of them. All that, everyone in Yerushalayim knew already. But that day, when he sent his question to the Chazon Ish, we saw his depth in learning.”

The Chazon Ish’s faith in the young man, plus his nurturing and life lessons, helped shape a gadol who bridged the litvish-chassidic divide and has an appeal that endears him to all types – from his father-in-law’s disciples to his own decades of talmidim to admorim, and even to those out of the yeshivah world

Depth and Breadth

With time Rav Moshe Bergman remarried and moved to his beloved Meron, where he was blessed with two daughters. He stayed in touch with his son through letters, and received updates from the Chazon Ish as well.

“His dear son, Meir Tzvi shetichyeh, is with me,” the Chazon Ish writes in one such letter, “and I was satisfied with him, his quick, clear understanding of the sugya.”

The bochur then moved on to the Lomza Yeshivah in Petach Tikva, becoming a chavrusa of the Chazon Ish’s nephew, Rav Chaim Kanievsky. Together, they learned over 20 masechtos.

(In our conversation, the Rosh Yeshivah shares this detail and emphatically adds a word. Twenty masechtos… be’iyun, in depth!)

Eventually the Chazon Ish suggested a shidduch between Meir Tzvi and Devorah, the daughter of Rav Elazar Menachem Mann Shach.

Rav Eliezer Yehuda Finkel attended the wedding, but he arrived after the kabbalas panim. Distraught about having missed the chance to hear a shtickel Torah from a promising young gaon, the Mirrer Rosh Yeshivah headed to the yichud room and pounded on the door, asking the new chassan to come out for a moment and share the shtickel Torah.

After the wedding, Rav Meir Tzvi settled in Bnei Brak near his in-laws and joined the chaburah that would later take on the name Kollel Chazon Ish. He learned first seder with Rav Yaakov Yisroel Kanievsky, the Steipler Gaon, brother-in-law of the Chazon Ish. After a few years, he became a maggid shiur at Yeshivat Ha’Darom-Kletzk of Rechovot, a position his father-in-law had held.

As would later become evident in his popular seforim, Shaarei Orah, Rav Meir Tzvi had absorbed not just the lomdus and penetrating depth of the Chazon Ish, but also the breadth — he could fuse halachah, Midrash, and a mastery of the more obscure parts of Shas.

An Armed Soldier

Those two decades were peaceful, but in the 1970s, a new era began.

Rav Moshe Bergman moved from Meron to Bnei Brak where he opened a yeshivah called Rashbi, bringing the light of Rabi Shimon bar Yochai to the city, especially to the immigrant population.

Rav Shach encouraged his son-in-law to form a kollel at the yeshivah, assuring him that he would still be able to “lig in learning,” to remain immersed in the sugya even as he assumed responsibility for the kollel’s payroll. With no choice, Rav Meir Tzvi began to travel.

Those treks may not have been his choice, but Rav Meir Tzvi’s visits became a gift to communities across the world.

A few years ago, I had the opportunity to sit with one of those balabatim upon whom the Torah world was built, faithful to talmidei chachamim, passionate and burning with achrayus to assist them. His name was Reb Yoel (Julius) Klugmann, and in addition to being a leader within the Khal Adas Jeshurun community in Washington Heights, he was also blessed with what Rav Elya Svei called “a shmeck,” a keen sense, for gedolei Yisrael.

And he was completely enamored of the Rosh Yeshivah, Rav Meir Tzvi.

Mr. Klugmann once described his admiration for the Rosh Yeshivah, showing me how the Avos d’Rabi Nosson refers to a talmid chacham with the term “gibbor mezuyan — an armed soldier.”

“Today,” he told me, “I quoted a Chazal to Rabbi Bergman, and he instantly replied, ‘Nisht doh aza a gemara, nisht doh aza a midrash. There is no such gemara and no such midrash.’ You know, when a person sees a soldier in all his glory, with his medals and weapons, it’s impressive. Rabbi Bergman has that effect on me.”

Not just on Mr. Klugmann.

The Rosh Yeshivah has an appeal that endears him to various types and sorts. Perhaps it’s because he is familiar with the Torah of all streams, able to easily quote from chassidish or Sephardic seforim.

Perhaps it is because the yeshivah, Rashbi, which his father originally opened to serve the immigrants arriving from North Africa, continues to be a place of pure Torah where talmidei chachamim of all demographics are welcomed.

Rav Meir Tzvi is the son-in-law of the towering litvishe gadol of the last half century, the commander-in-chief of the yeshivah world, yet in his yeshivah, the piyut of Bar Yochai is sung every Leil Shabbos before Maariv.

The Rosh Yeshivah’s sister is married to the current Alexander Rebbe, and the Rosh Yeshivah often visits to show respect to his younger brother-in-law, following the chassidish protocol of being mazkir himself to the Rebbe with his name and that of his mother. (Another sister married Rav Yaakov, son of Rav Mordechai Goldman of Zvehil — grandson of Rav Shloim’ke.)

Rav Meir Tzvi Bergman’s Torah is vast and deep, and his ahavas Yisrael — and appreciation for all sorts of Yidden — reflects that.

In America, Rabbi Shlomo Lesin, himself an accomplished builder of Torah, is the closest person to the Rosh Yeshivah. Rav Elya Svei entrusted him with mission of helping Rav Meir Tzvi and he has cherished that charge ever since.

He reflects on the ahavas Torah of Rav Meir Tzvi. “It would certainly be easier and more pleasant for him to sit in his kollel, but he is driven by a sense of responsibility to ensure that others can learn Torah with menuchas hanefesh.”

And somehow he manages to summon the menuchas hanefesh he himself needs even under less than ideal conditions. “Whether it’s here, in America, in Panama, or in Antwerp, the Rosh Yeshivah is content if he has a bench, a Gemara and a notebook, and then he is back at home. He needs little else.”

(Along with his classic seforim, the Rosh Yeshivah has authored a special kuntres of the chiddushim developed while he was in transit on behalf of the yeshivah.)

“Whether in America, in Panama or in Antwerp, the Rosh Yeshiva is content if he has a bench, a Gemara and a notebook. He needs little else”

My Reward

I once had the opportunity to visit Rav Meir Tzvi at the small Boro Park apartment in which he was staying.

He had come with no gabbaim, drivers, or advance team, perfectly content to prepare himself a coffee and daven minchah in the back of Shomrei Shabbos.

On that day, we spoke of… kavod haTorah.

He shared a vort in the name of Rav Shaul Amsterdam. In Maseches Shabbos (118b) a list of Amoraim appears; each one shares a custom or practice which they consider to be a personal source of merit.

Rava said, “May I receive my reward, because when a young Torah scholar comes before me for judgment, I do not rest my head on the pillow until I see as many of his merits as possible….”

Rashi there explains the words “teisi li” as “yeshulam schari,” may I receive my reward — even though Rava is not the first Amora mentioned on the list as using those words, Abaye having used them a line earlier.

Why does Rashi wait until Rava’s statement to explain the term?

In the small Boro Park basement with a narrow window at sidewalk level looking out at the shoes of passersby, the Rosh Yeshivah smiled a radiant smile and quoted a gemara earlier in the same masechta (23b).

Amar Rava… one who loves talmidei chachamim will have children who are talmidei chachamim.

“Do you hear? Here, Rava is saying that he was always careful to do his best to help talmidei chachamim, and he is hopeful he will get a reward. Which reward? Money? Honor? No,” concluded Rav Meir Tzvi, his voice rising, “he wanted his reward, the reward that he identified earlier in the masechta. That’s what Rashi is saying — yeshulam schari, let me get that reward please, Ribbono shel Olam, the one I taught previously — the reward of banim talmidei chachamim!”

On that day, I noticed a brochure on the table, probably left there by a previous visitor. It advertised a program in which yungeleit could earn extra money by mastering a particular sefer. I imagined that the Rosh Yeshivah, who carries the welfare of hundreds of yungeleit on his shoulders, would be pleased with the initiative.

He was not.

“Kavod haTorah means that a yungerman who is learning Eiruvin is living Eiruvin. He’s breathing Eiruvin. Of course, he needs to learn other limudim — a person has to learn the parshah, to learn mussar, to learn halachah l’maiseh, — but his schedule should revolve around Eiruvin. He should have enough money not to have to sell that devotion to Eiruvin for anything else, to be pulled away — even by a holy sefer. That’s not his program.”

I wondered if the Rosh Yeshivah was going to share this original take in public, since the program being promoted in the brochure was well publicized, with prominent backing.

“My talmidim know what I hold,” he said. It was clear that he considered that to be more than enough.

That conversation ended with a vort, also about kavod haTorah. We were discussing Mr. Klugmann, who had recently passed away.

Chazal (Kesubos 111b) ask what is meant by the mandate of Bo sidbok, to cleave to Hashem. Is it possible for a human being to cleave to the Shechinah? The Gemara explains that it refers to being attached to a talmid chacham, giving the example of one who does business with talmidei chachamim.

In that stuffy room, the Rosh Yeshivah used a shiur klali niggun. “Ich farshtei nit. Isn’t there an obligation to help every Yid in need? Doesn’t the Rambam pasken that helping someone establish themselves in business is the highest sort of tzedakah? What, then, is the special din of doing business with a talmid chacham?”

Rav Meir Tzvi paused, then stroked his beard and answered. “I think voss shteit duh, what it says there is: Certainly, Hashem is right next to the impoverished one, as the pasuk says, He is yaamod l’yemin evyon, standing to the right of the pauper. But that isn’t dveikus. It’s being close to Hashem, but not attached to Hashem.

“But Torah? Torah becomes a part of a person, it fills him, making his essence Torah, so when you benefit a talmid chacham, you are actually connecting to Hashem!”

With Rav Hutner and Rav Ruderman. “Rav Hutner told me that in any conversation with Rav Aharon Kotler, he’d do anything to get Rav Aharon to say the word ‘Torah’”

One Word

That was several years ago.

This week, when I again had the zechus to speak with the Rosh Yeshivah, he confirmed that with Hashem’s help, he is hoping to visit America for the upcoming Adirei HaTorah event in Philadelphia in support of full-time Torah learners.

Lacking the strength, the Rosh Yeshivah has not made the exhausting trip to the United States in several years, and even now, he does not really know how he will be able to undertake it.

But… kavod haTorah.

“My shver was a nephew of Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer, the father-in-law of Rav Aharon Kotler, and I heard the way he spoke about the Lakewood Rosh Yeshivah. Rav Ahron had a dream for America, he wanted to create something, and he invested all his kochos into this dream. It came true, it’s happening, and it is a big zechus for me to be able to take part in this gathering.”

Over the years the Rosh Yeshivah has seen a difference not just in the number of yungeleit in kollel, but also in their caliber.

“There are real avreichim, like the ones in Bnei Brak, across the world today. This generation has merit. I have seen them in South America, in Europe, in the chassidish communities as well — not just in Lakewood. We see genuine avreichim who want nothing in life outside of ameilus baTorah, and they have serious hasagos in learning, real goals. Nothing else makes them happy. This is Rav Aharon’s zechus.”

The Rosh Yeshivah makes his point by sharing a personal memory.

Many years ago, he was standing on a street corner on a rainy morning, headed from Boro Park to Williamsburg. There was a van service that ran the route, and the Rosh Yeshivah waited at the designated stop with a small sized Gemara in his hands.

The van was delayed. The rain grew harder. The Rosh Yeshivah was wet, water dripping from his hat. A dark luxury car pulled up at the corner, inches from where the Rosh Yeshivah stood, and the driver, a visibly frum Yid, looked disdainfully at the man standing there, looking into his Gemara.

The light turned green. Before pulling out, the driver offered a one-word assessment of the situation, his take on the man standing in the rain engrossed in the small Gemara.

“Torah,” said the driver derisively, pronouncing it “tei-reh,” mocking what he imagined a litvish-accented Rosh Yeshivah sounded like.

That was the story.

The van came soon after, and the Rosh Yeshivah continued with his day, contemplating the incident.

“I was not hurt,” he told me. “I was fascinated.”

The previous day, he explains, he had gone to visit Rav Yitzchok Hutner, with whom he was very close.

“And Rav Hutner told me that in any conversation with Rav Aharon Kotler, he did whatever he could to direct the conversation so that Rav Aharon should have to use a particular word. What was the word? It was ‘Torah.’

“Rav Hutner heard such deep emotion in the way which Rav Aharon said that one word, that he tried to make Rav Aharon say it again. It moved him deeply. And on the van, I was thinking about this, how one Yid had used the word ‘Torah’ mockingly, while when Rav Aharon used that same word, Rav Hutner heard music.

“The driver of that car was not a bad person, but he never been exposed to the beauty of what Torah is, and it’s a rachmanus, I felt bad for him. Rav Aharon, however, had tasted the joy in each letter of Torah, and his feeling for it was audible to those with sophisticated hearing.”

At last year’s Adirei HaTorah event. With Rav Bergman as this year’s guest, everyone will be singing the same song

There will be many people in Wells Fargo Center on Sunday night, with Hashem’s help. They will come from different communities, but they will be united in their shared appreciation for this word, “Torah,” and for the legions who have made it the center of their lives.

Who was driving that dark sedan on a rainy Boro Park morning 50 years ago? I have no idea, but it is entirely possible that his son or grandson will be in the stands, part of the groundswell of Jews who, with their presence, with their hearts, with their choices, are all singing the same song, a song that has just one word in it, a single lyric.

Torah.

It is a song of reverence, appreciation and love, a response to all that Rav Aharon Kotler invested in that very same word.

Torah, he said — and they will respond, yes, Torah!

And when they sing that song, do you know who will be there to hear it?

The Rosh Yeshivah who stood there with his small Gemara, humbly waiting for a van that would take him to the next stop on his journey, a journey that is lined with ameilus in Torah, harbatzas Torah, and hachzakas Torah.

Now the van stops yet again, and this time, is it is for simchas haTorah.

To celebrate Torah, to remember those who planted seeds, and to marvel at what has come forth.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 963)

Oops! We could not locate your form.