He Never Ran

Zaidy Morgenstern showed me that survival comes in many shapes and forms

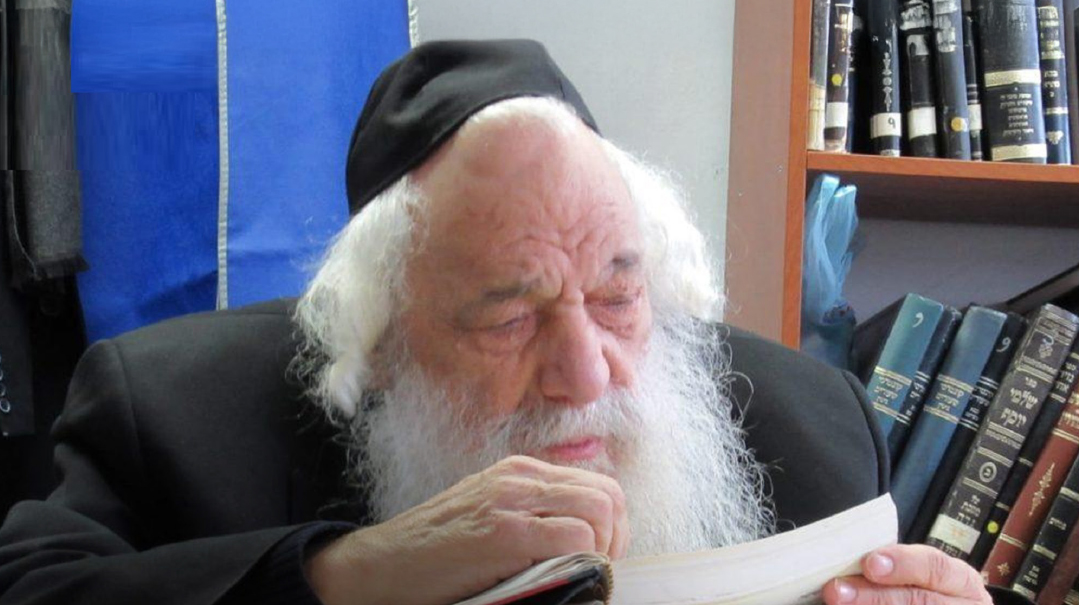

Photos: Meir Haltovsky, Family archives

When I married, I got gifts — a watch, cuff links, an esrog box, stuff like that — and also, new grandfathers and grandmothers.

Zaidy Morgenstern was a novelty to me, a different sort than I was used to.

His English was accent-free (well, not completely, but it wasn’t a Polish, Hungarian, or Czech accent, like other Zaidies, though he did say “Wiyamsburg” instead of Williamsburg), and he had no numbers on his arm.

But from him I learned that survival comes in many shapes and forms.

He was not a big man, but he stood big, and over time, I realized that the stories he told had a single thread connecting them. Life would take him to several different stations, each with its own tests and triumphs. Through it all, the values honed on the streets of East New York guided him: loyalty, resourcefulness, grit, and the instinct to look out for the little guy.

G

ershon Morgenstern was born in the early summer of 1933, to parents who had come from the Polish town of Długosiodło, near Warsaw, after the First World War. His father worked long hours laying linoleum, a popular business at the time, but it was a struggle to make ends meet, and the family lived in a cramped apartment that had only cold water.

Unlike Williamsburg and the Lower East Side, where Yiddishkeit thrived, Zaidy told me, East New York did not have too many bnei Torah. Though local housewives haggled over the price of pickles or salami in Yiddish and there were more than 70 shuls and landsmanchaft clubs — the guiding philosophy was not Torah, but Socialism, the carpenters, merchants, and tailors of the neighborhood eager to work hard for a government they respected.

Only old men davened in the shtiblach — among them his Zaidy, whom he revered. He joined his grandfather every Shabbos in a small basement on Powell Street. After davening, the men made kiddush on a homemade brew they called White Lightning, 90 percent alcohol. Seven-year-old George would get a cup as well — perhaps a l’chayim for a future that appeared not very bright? — as the old men gazed hopefully at the lone child among them.

Along with being bullied by the Italian and African American kids on the street, little George also had to deal with the mockery of the Jewish kids, who considered yeshivah guys to be wimpy, bookish, and anemic, holding on to an irrelevant past. He learned to hold his ground, to meet their stares, and to walk by them with his shoulders squared.

In a neighborhood where everyone was poor, his parents were even poorer. The only way he could afford a ten-cent knish, the popular after-school treat among his friends, was by carrying home the heavy pile of schoolbooks for another boy.

But then a new kid came into the class, an orphan, who was even smaller than he was, who had less. So Georgie became his protector.

“If you mess with him, you’re messing with me,” he learned to say, and the ten-cent knish was broken into two pieces and divided.

He and his friends attended Rabbi Yitzchak Schmidman’s Yeshivah Toras Chaim. Unlike public schools, which were free, the frum schools had to charge tuition in order to pay their own rebbeim and teachers.

Zaidy’s father could not afford the tuition, but Zaidy’s mother found a way. Three mornings a week, she strapped her baby into the carriage and walked over a mile to the school. There, she worked in the kitchen until three o’clock, cooking and cleaning up after the students in lieu of tuition.

On Sundays, when there was a lot of traffic at the Jewish cemetery on Staten Island, she took a pushke and stood there, collecting for Bais Rikvah. Those nickels and dimes were then used to put her daughter through school.

Life was not black and white. One Shabbos afternoon, little George saw his rebbi — the rebbi who slapped him for not knowing his Mishnayos — sitting with a group of friends, playing cards. The rebbi was not wearing a yarmulke, and he was smoking a cigarette.

In tears, the child ran to his Zaide Shloyma for comfort. The zaide understood him, and told him that while the Torah is perfect, people are not.

Somehow, despite the difficulty in finding staff who shared his ideals, Rabbi Schmidman invested the boys with spirit and spunk.

Zaidy told me about Abe Stark, proprietor of 3-G Clothing. The store was famous because there was a sign on the left field fence in Ebbets Field, home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, that challenged the players: hit sign win suit.

Abe Stark was president of the Pitkin Avenue Storeowners Association and George and his buddies went into his office one day to petition. They wanted to know why Friday was the official day off for the merchants up and down the avenue. Why could it not be Shabbos?

He recalled how Mr. Stark couldn’t help them, but he did roll up his shirtsleeves to show them fresh tefillin marks, as if to reassure them that he was doing his best.

Zaidy and his friends were surviving America, their way.

In what would become a tragic trend, some of the local shuls started selling their buildings to houses of worship of other faiths. In one former shul, young George noticed that the seforim had remained inside the chapel, and he went to ask the nun for permission to remove the Jewish holy books.

Permission was denied, so George gathered together his buddies and tried again. He asked the nun if they could have a religious discussion, since he had questions. Sure, she said, welcoming him to the office.

George asked one question, then another, allowing the nun to expound while the other boys worked quickly to cart out the seforim. When the last sefer was safely outside, George cut her off in mid-sentence, and walked out.

A few of the teenagers in that congregation heard about what happened and they gave chase, beating the little Jewish boy who had spearheaded the campaign to save the seforim. Bloodied, little George sought relief. There was no money for a doctor, so he and a friend headed to the pharmacy, where the pharmacist concocted a healing ointment and administered it to the wound. As he worked, a tall, broad Jewish sailor sat quietly at the counter, sipping a chocolate soda and watching them.

As George and his friend were leaving the pharmacy, they saw a group of African American teenagers heading toward them, some of them holding knives.

The yeshivah boys stepped back into the pharmacy, asking if there was a rear entrance from which they could escape. Suddenly, the sailor put down his chocolate soda and stood up.

He rose to his full height, and with an arm around each boy, he led them back outside to face the crowd. The sailor stood there, staring at the approaching gang with a hard calm. The posse hesitated as they saw his expression, and decided to turn back instead.

“We Jews don’t run. We fight,” the sailor said.

Zaidy would remember those words.

A

fter graduating elementary school, Zaidy expected to join most of his classmates at Thomas Jefferson High. His mother took him to enroll in the school, and while she filled out the paperwork, he went to look around.

He was struck by the realization that in a school in which the student body was 90 percent Jewish, not one boy was wearing a yarmulke, and he informed his mother that this was no place for him.

Jews don’t run, the sailor had told him. What were they ashamed of?

Yeshivas Rabbeinu Chaim Berlin was a real yeshivah. Its name and reputation were intimidating to the teenage boy, but he was ready to give it a try.

There, in the former bank headquarters on Stone Avenue, he found a treasure — the authenticity he had been craving. When it came time for Zaidy to graduate from high school, however, there was a problem. Just before the ceremony, one of the administrators informed him that he would not be getting a diploma since there was still outstanding tuition debt.

The administrator was no match for the teenager from Brownsville. George squared his shoulders and spoke quietly, but firmly.

“Listen to me,” he said. “My mother is in the audience, and she worked hard for this moment, to see me get my diploma. My name will be called and you will then give me a rolled-up piece of paper. I don’t care what’s on it, but my mother will get the nachas she deserves.”

Jews don’t run.

The sixteen-year-old graduate added a condition. “If you accommodate me, I assure you that Chaim Berlin will not lose out.” He got the piece of paper — and his mother, a moment of satisfaction.

Z

aidy continued in the beis medrash of Chaim Berlin, becoming a talmid of Rav Yitzchak Hutner, to whom he referred simply as “the Rosh Yeshivah” for the rest of his life.

Rav Hutner had the power to invest a street kid with grandeur and glory — he built an army that way! — teaching children who grew up revering Jackie Robinson and Superman that there is nothing more exalted than a ben Torah.

The pride, the gaavasan shel Yisrael, transmitted by Rav Hutner revealed the depth of the sailor’s comment: It was less about brawn and bluster, more about a quiet, restrained dignity, the understanding that we descend from people who refused to bow.

With Rav Hutner’s permission, Zaidy became the first talmid to attend Brooklyn College, and there, George Morgenstern was the first student to insist on wearing his yarmulke during classes.

Here too, the odds were against him, because unlike the other students, he did not have the money to buy the required textbooks. He got by, borrowing the textbooks from others for a few minutes before and after class, yet he outshone them academically and earned a degree in advanced mathematics.

HE

was only 20 years old when he married his wife Faigy — Bubby, shetichyeh — and they started a new life together. He took on the title of kollel yungerman in an era when you could fit all the yungeleit in the country into the smallest section of the Wells Fargo Center.

Bubby worked as a secretary, and if she left work precisely on time and there were no delays on the train from Manhattan to Brooklyn, she might get to see her new husband for a few minutes between second seder and night college.

After a year in kollel, Zaidy wanted his wife to stop working. She had seen a newspaper ad that Sylvania Electric Products, based in Boston, was looking for mathematicians, and Zaidy called to inquire.

They invited him to come for an interview and he wondered how he would get from New York to Boston. When he learned that he was meant to fly at the company’s expense, he didn’t hesitate.

He had long been fascinated by airplanes, and now, he would get to realize a dream of actually traveling on one! Wide-eyed, he boarded a plane and traveled to faraway Boston, filled with a sense of adventure.

He got the job, and the family moved, settling in Lynn, Massachusetts — where, at the time, the lone Orthodox shul in town happened to have a rabbinic vacancy. He applied for that job as well, making it abundantly clear in his conversations with the board of directors that his view of the job of a rav was not to make life easier for the people, but to lift them up.

He wouldn’t run.

At Sylvania, he made a discovery that would prove central to his future. Most of his colleagues had gone to Yale or MIT; he was the only one who had gone to Brooklyn College. He soon realized that, even if they had the more prestigious education, years in yeshivah had trained him to think differently, to connect dots that appear unrelated, to analyze an idea and find new solutions.

He was promoted, rising to the top of the department. During the week, things were relatively simple, but Shabbos presented a different sort of challenge.

The members in the shul had learned that Rabbi Morgenstern didn’t back down from what he thought was right. The mechitzah was raised to fit his standards and the zemanim adjusted to meet the demands of halachah. But then the president of the shul called the rabbi with a personal request.

His mother had passed away, and he expected his rabbi to attend the funeral, which was being held at the Conservative temple in town. He made it clear that he would be deeply offended if the rabbi was not there for him at this vulnerable time, and Zaidy was unsure how to proceed. He called his mashgiach from yeshivah, Rav Avigdor Miller, who had himself served as a rabbi in a Massachusetts community and well understood the dilemma.

“Gershon, stand firm,” he said. “Stand firm.”

Jews don’t run.

Rabbi Morgenstern phoned the president and explained that he would not be attending the funeral. “Will you come to the meal in my house afterward?” the president asked.

Zaidy called Rabbi Miller, who told him there was no reason not to accommodate that request.

That evening, Zaidy went to the president’s home, unsure if he still had a job. When he entered, the president said, “Oh, Rabbi Morgenstern, I was waiting for you.”

Zaidy took a deep breath, assuming he was about to be fired. Instead, after a moment of silence, the president addressed his guests. “Ladies and gentlemen, I would like you to meet my rabbi, a rabbi who has principles and is prepared to stand by them.”

Jews don’t run. Stand firm.

O

ver the years, Zaidy would meet people who told him that they had succeeded in business. Always, he asked the same question.

“It’s nice that Hashem granted you success,” he would say, “but tell me; how many people have you brought along with you?”

Success can only be enjoyed if it is shared.

One day, a yeshivah guy showed up at Sylvania. He had been hoping for a job, but he had failed the aptitude test.

Zaidy went to the manager who administered the test, and asked if he might take it, out of curiosity. The manager agreed, Zaidy sat down to take it — and flunked. On purpose. (If you knew him, you know that this might have been the ultimate act of sacrifice — to fail a test for another Yid!). The manager was shocked.

“Morgenstern, if you can fail the test, then it must be inherently flawed,” he said, and went on to hire the applicant he’d rejected.

Now the man had a job, but Zaidy understood his responsibility to the company as well. He invested hours of his own time to train in the new hire, ensuring that he would deliver.

IN

the early 1960s, Zaidy felt ready to open a technology company of his own, and he and Bubby both wanted to move back home, closer to their families. They started out in Crown Heights, but Zaidy had a dream.

As a chassan, he had been determined to buy a ring for his kallah, knowing that the only way to make that happen was to earn the money on his own. He found a waitering job at a Sam Kasten’s kosher hotel in Spring Valley, New York, working over Succos, Pesach, and the following Succos, and saved every dollar. He came for the money, perhaps, but he found himself charmed by the thick pine trees, the fragrance carried by the soft breeze and the rolling hills.

He wanted to live in Spring Valley, always. Life could be a resort. Bubby was hesitant; how would her parents make their way from the concrete maze of the city up to the mountains?

Zaidy assured her that they would only have to travel until the end of the rail line in Manhattan, and he would meet them there and drive them the rest of the way.

She agreed.

Sam Kasten, Zaidy’s one-time employer, informed him that the future of the Jewish community was not in Spring Valley anymore, but up the hill in Monsey, and Zaidy and Bubby purchased their first house, on Locust Hollow Drive.

A house! With bedrooms and stairs and several washrooms and wooden floors! For a boy who had grown up in a tenement where the bathtub was in the kitchen, usable only at night when everyone else was asleep!

While Beis Medrash Elyon was firmly established on Monsey’s Main Street, the neighborhood “up the hill” was just starting to happen. Shuls were opening, schools were being established, chesed organizations were being launched — and Zaidy and Bubby were right there.

T

heir chesed was not confined to off-hours. Computer programming was rapidly becoming a respectable, lucrative source of parnassah, and Zaidy’s company, Data Systems and Software Integrated, saw the opportunity this presented for yeshivah graduates.

Tens, then hundreds of young men passed through the company during those years, and, as one of them told me, “We went to Morgenstern University, and along with the necessary skills, we learned about yashrus, erlichkeit, and the mandate to make a kiddush Hashem.”

At DSSI, Zaidy developed sonar systems that were sophisticated enough to attract the attention of the United States military. Zaidy was invited to a meeting at a secure army base, seated around a table with some of the country’s most prominent military intelligence officers. He would describe the arrogance of the men in the room, and the way one general, in particular, found Zaidy’s yarmulke to be distasteful.

It bothered him that rather than claim credit for a brilliant innovation, the young engineer insisted that there was a Power greater than he. Zaidy was mocked — for the yarmulke, for refusing to partake of the food, for the blessing he made before sipping water — and he stood ever straighter.

The sailor had taught him well.

In time, the Israeli government learned about the engineer in Monsey. The man who thought he was dreaming when he was flown from New York to Boston was flown across the ocean and welcomed at Lod Airport by a team of officials, shown around the ancient, holy country and given the chance to help its military.

And there, too, he told them his theory about yeshivah guys — about their creativity, work ethic, and erlichkeit, well understanding the cultural divide in that country. And of course, he told them about the sailor, sharing a lesson learned early on about courage and self-respect.

HE

was voted in as president of Yeshivah of Spring Valley, bringing the creativity and innovation that had pushed him to build new data systems to this role as well.

A friend of mine recalls growing up in Monsey of those years. A student at the school, he occasionally found himself on the hard wooden bench outside the principal’s office — not because of any misbehavior, but because his parents could not pay tuition.

And then, one day, everything changed. There was a new president, and he was now welcome in class.

A new president — who knew what it felt like when a child wants to learn, even if his parents can’t afford to pay tuition.

YSV might well have been the first frum school to implement a pension fund for rebbeim, an idea Zaidy took from corporate America. At the shivah, an older man came in, a retired rebbi. “Thanks to George,” he said quietly, “I still have my dignity.”

His rebbi smoked on Shabbos. A generation later, the rebbeim in the school of which he was president got a pension.

Don’t retreat. Move forward. Build.

N

ot long after his bar mitzvah, he entered Chaim Berlin, and the influence of the Rosh Yeshivah would shape his life.

From that moment on, he aspired to be the ben Torah that Rav Hutner described. Until the end of his life, Zaidy had a serious daily chavrusa in Gemara, but he also learned mussar afterwards, like a ben Torah ought to.

He walked like a Chaim Berliner, he spoke like a Chaim Berliner, (pronouncing it not Chazon Ish, but Cha-zoin Ish, for example) and most of all, he lived like a Chaim Berliner, refusing to compromise when it came to Shulchan Aruch — whether in business, in askanus, or in the chinuch of his own children, exhibiting the tenacity that comes not from being inflexible, but from being anchored.

A few years ago, Zaidy was telling me about a grandchild for whom he was davening fervently. When he spoke about it, his eyes flashed with the courage and resolve of the kid from Brownsville, his determination so raw it smelled like the oil and dust of the “El” train that roared just above the streets that raised him.

Rav Hutner was sandek for both of Zaidy’s sons, and blessed his talmid that these children would also be bnei Torah, the aspiration that defined Zaidy and Bubby. That hope would be fulfilled, as Zaidy merited two sons and three sons-in-law, each of whom is at home in the beis medrash.

On Erev Yom Kippur, the phone rang throughout the day in Zaidy’s home, children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren calling for a brachah. To each, he read the nusach printed in the machzor, then he would add a Yiddish brachah of his own.

A few years ago, a grandson called from Lakewood and received the usual brachah. He was about to hang up when he heard soft weeping. It was Zaidy crying on the phone.

This was unusual.

He waited, unsure of what to say, and Zaidy finally spoke. “You know, you’re one of my only eineklach still in kollel,” Zaidy said. “Lots of them went to work in recent years. You are still learning. Keep it up! This is my nachas!”

And then Zaidy hung up, a rare moment of pure emotion from a person who kept so much inside. From that year on, every Erev Yom Kippur, Zaidy would cry after giving a brachah to this particular grandson, though he no longer had to explain why.

He was niftar on Shabbos, 9 Kislev. Bubby told me that frankly, she had been hopeful that the levayah could be held on Sunday morning, when a larger crowd would be able to attend. She wanted him to have this final honor.

Her eldest son, my Uncle Dovi, a respected rav and posek in Monsey, told her that he felt that the right thing to do was to hold the levayah that night, after Shabbos, even if it meant a smaller crowd; it was what halachah and kevod hameis dictated.

And though Zaidy wasn’t there to guide her, she got it. (And the crowd filled the room, the hallway, and spilled out into the parking lot.)

Jews don’t run can mean many things — a call for discipline, when emotion is pulling in a different direction, or the surrender of instinct to principle, the highest form of strength. Stand firm, Rabbi Miller had urged.

Gershon ben Sholom Aryeh was laid to rest in Monsey on a cold Motzaei Shabbos, in accordance with what was halachah recommends, as instructed by his own son! It was everything he could have dreamed of.

He had never run, never retreated, and never faltered, and his final journey reflected every step he had taken along the way.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1091)

Oops! We could not locate your form.