He Longs to Hear Your Voice

| July 18, 2023Singing of hope and endurance in the killing fields of Europe

While our ancestors were being hounded, persecuted, and slaughtered, our grandparents herded into ghettos, imprisoned in sub-human barracks, marched to slave labor, or forced to dig their own graves, were melodies of hope still on their lips, even in places of deepest darkness?

Guides who have led thousands back to the tragic sites of our people’s suffering share the songs and stories that managed to open hearts in the Valley of the Shadow of Death

How Wonderful Our Portion

RABBI MENACHEM NISSEL

Author of Rigshei Lev – Women and Tefillah, rosh mesivta at Yishrei Lev, seminary lecturer, and Senior Educator for NCSY

The classic “Ashreinu mah tov chelkeinu, umah na’im goraleinu” is a perennial heart-thumping, foot-stomping essential for every heimish shul’s Simchas Torah hakafos. But for myself and my students whom I take to Poland, it has special meaning.

As the saying goes, it’s not pashut to be a pashuter Yid. Rabbi Yosef Friedenson a”h, legendary journalist and Auschwitz survivor, shared a story that is the essence of everything beautiful and inspiring in a “simple Jew.”

He described a Hungarian Yid name Binyomin, who occupied the cold slab of splintered plywood next to him in his bunk in Barrack 22. Every morning Binyomin would be moser nefesh to get up before dawn and daven with tefillin he had managed to hide. Just after Birchos Hashachar, as he reached the words “Ashreinu mah tov chelkeinu,” he would say each word with great kavanah, translating into Yiddish as he went along:

“Ashreinu — we are so fortunate! Mah tov chelkeinu — how wonderful is our portion! Umah na’im goraleinu — and how sweet is our lot!” He would then sing this again and again, maybe ten times.

In the words of Rabbi Friedenson: “Can you begin to imagine? Here was a person squeezed into a barrack, suffering terrible hunger pains, living in the shadow of billowing chimneys of the crematoria where his family and thousands of fellow Jews were murdered daily, whose highest ambition for the day was to survive another day of backbreaking labor under the iron hand of the Nazi beast, and yet he wakes in the morning to rejoice that he is a Yid!”

When I tell this story, I suggest to my students that they underline this song in their siddur. It precedes what I call the “Martyrs’ Shema,” which ends with the powerful brachah, “Mekadesh es Shimcha barabim — Who sanctifies Your Name in public.” Some say that this is the brachah one says before dying al kiddush Hashem. I challenge my students to take a few moments every morning to connect to Binyomin, and to the countless kedoshim throughout the generations, from Rabi Akiva to the victims of present-day terror, whose neshamos ascended with the words of the Shema, and to sing “Ashreinu” with the niggun that was sanctified by Binyomin — to start their day rejoicing in our Jewishness with the ultimate inspiration.

What happened to Binyomin? Rabbi Friedenson shared that one day, Binyomin heard that the Nazis would make a selektzia for people to work in the crematoria. He began to shake uncontrollably at the thought that he’d be selected to throw other Yidden into the furnaces. His normal cheerful nature disappeared. He became a mere shadow of himself and was selected to go to the gas chambers. His last words were, “Today is much better for me than the day of the previous selection. It’s much easier to go to Olam Haba with clean hands….”

Up from the Ashes

RABBI NAFTALI SCHIFF

Founder and chair of JROOTS, which organizes 150 trips each year for Jews of all ages, backgrounds, and communities

Our theme throughout our journeys in Poland is very much about “Mekimi me’afar dal,” how Hashem has brought us up from the ashes, and as such, more somber niggunim will often give way to songs of hope, bitachon, and yeshuah. Naturally, the niggunim — which are part of the tour experience — will vary depending on what type of group it is. For the less-affiliated participants, the messages of “Od Avinu Chai” and “Am Yisrael Chai” are enormously powerful.

During bein hameitzarim of 2006, we took a group of 60 rabbis from Aish HaTorah on an epic journey through Poland led by Rosh Yeshivah Rav Noach Weinberg a”h. In Yeshivas Chachmei Lublin, the Rosh Yeshivah related how the Nazis threw thousands upon thousands of seforim out of windows and ordered the Yidden to dance on them. They began to dance and sing “Ashreinu mah tov chelkeinu” with more and more gusto, turning the aveilus into the simchah of avodas Hashem — until the Nazis yemach shemam decided to shoot them and stop the holy scene.

By the killing pits of the Tarnow forest, where whole families and hundreds of Jewish children were shot and left to die on top of one another, we ask the students on our tours to think deeply about their families and what they mean to them, then write letters to give or mail to their parents at home. We sing a very emotional “Umachah Hashem Dimah,” asking Hashem to wipe the tears off every face and bring an end to all our people’s suffering, with the Geulah.

In Treblinka, we relate the story of the famous “Ani Maamin” that was composed by Reb Azriel David Fastag on the train to Treblinka and given to a bochur who managed to jump out the train’s window and eventually bring the holy niggun to the Modzitzer Rebbe. There’s also the old “Lulei Sorascha,” which was one of the first niggunim brought from war-ravaged Europe to America by a Yid named Rubenstein, who arrived at the offices of the Vaad Hatzalah still during the war, having escaped Auschwitz with his emunah and bitachon intact.

One of the survivors who accompanied many of our trips, Reb Leizer Kleinman a”h, had formerly been a Satmar chassid. He lost all of his family during the war, and afterward he left observance behind. When I interviewed him 60 years later, the first niggun he remembered from his childhood was, chillingly, “Shebeshifleinu zachar lanu ki le’olam chasdo, vayifrekeinu mitzareinu — He remembered us in our lowest times, because His kindness is forever.”

After having left everything, Reb Leizer eventually returned to Yiddishkeit, and he married a Jewish woman when he was already in his 80s. He began accompanying our JROOTS journeys and had become a true baal teshuvah. On the last few trips that he joined, the group always sang that niggun, as well as his favorite, “Tov Lehodos,” and he’d even recall for us the alef-beis niggun he’d chanted in cheder in Satmar, where he’d been taken as a three-year-old to lick the honey.

Reb Yosef Lefkowitz, who survived seven concentration camps and saved hundreds of Jewish children from convents and Christian homes after the war, accompanies our trips until today. No family survived from his childhood home in Cracow, but Reb Yosef still sings his way through Poland with Bobover niggunim he remembers from the tish of the Kedushas Tzion. There’s a vintage Lecha Dodi, a “Tzavei” that was sung back then, and many more.

We Have Not Forgotten Your Name

RABBI PAYSACH KROHN

Mohel, author, lecturer, and European tour leader

Theresienstadt, in the Czech Republic, was a ghetto and prison camp where over 33,000 kedoshim were killed, and another 88,000 Yidden were forced onto transports to the death camps. It had another face too: The Nazis, yemach shemam, used Theresienstadt as a decoy, setting up a section of it as a “model camp” to fool the Red Cross delegations and the entire world. They had orchestras and lectures and soccer games to disguise the horrors.

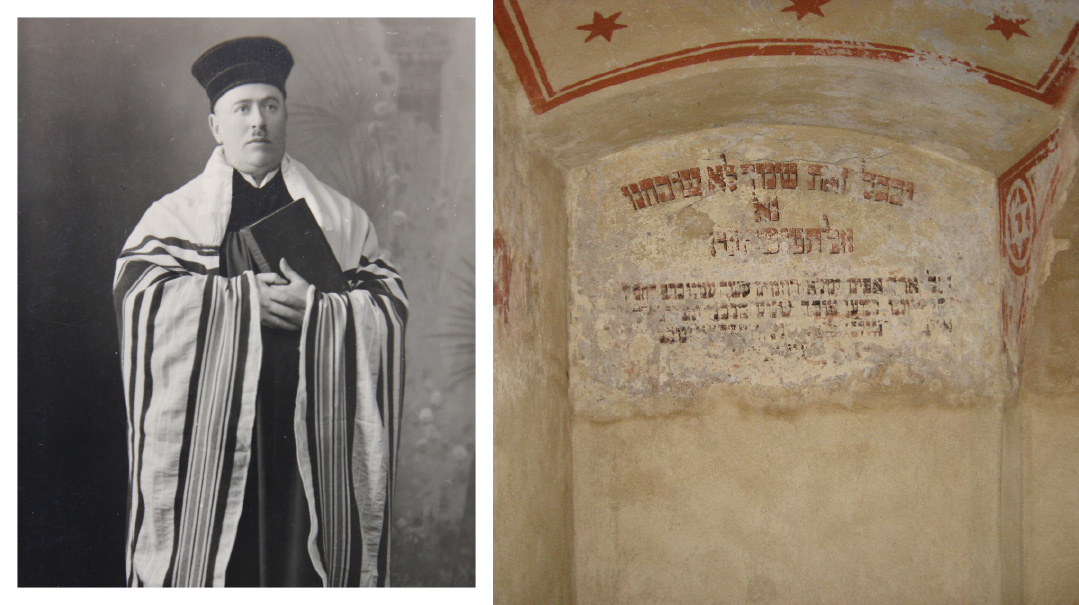

In that camp, in a cramped 15-foot square room between two buildings that the Nazi guards did not use, the imprisoned Yidden built themselves a shul. In the depths of squalor, with disease and starvation rampant, they built a place for prayer. The shul was decorated — and likely masterminded — by a German Jew, a chazzan, educator, and artist named Chazzan Asher Berlinger Hy”d. The pesukim that he hand-painted so artistically, in vivid red and purple calligraphy, can still be seen on the walls.

Chazzan Berlinger was a scholar who had learned at the Wurzburg Seminary for teachers. He was also an artist and sculptor, and Yad Vashem has several lifelike sketches and illustrations that he drew in the concentration camp. They also have something else: In Theresienstadt, he created a luach with Hebrew and English dates, parshiyos, and the time of the molad, which he notes that he calculated according to the Rambam. Chazzan Berlinger gathered the Jewish children around him to teach them, officially teaching art, but also offering chizuk and hope and Yiddishkeit.

Asher Berlinger did not survive the war. After two years in Theresienstadt, his turn came to be deported eastward. But his two daughters, Mrs. Senta Buck a”h (who later lived in London) and Mrs. Rosie Baum (now of Detroit), had previously been sent to England on a Kindertransport, perpetuating their parents’ legacy in this world.

I can never forget how our group davened and sang in the Hidden Synagogue of Theresienstadt, where those Yidden davened. The pesukim remain on the walls, and this is what they say: As in many shuls, “Da lifnei mi atah omeid — know before Whom you are standing.” Then there’s the pasuk, “Ana, shuv meicharon’cha — Please turn back from Your anger and have mercy on the treasured people You have chosen.” And “Uvechol zos Shimcha lo shachachnu, nah al tishkacheinu — With all this, we have not forgotten Your name, please do not forget us.”

Standing there, we davened and we cried and we sang Abish Brodt’s song, “Habeit Mishamayim Ure’ei.”

But there were other pesukim on the wall as well. As he languished in the camp, stripped of his family and his property, his dignity and his position, Asher Berlinger’s emunah was strong and pure. He wrote “Vesechezenah eineinu — May our eyes see the return to Zion,” and he wrote, “Im eshkacheich Yerushalayim tishkach yemini — If I forget you, Jerusalem….”

Because whatever our nation has gone through, they never stopped mourning Jerusalem and awaiting its rebuilding. Of course, we sang “Im Eshkocheich.”

If I live to be 160, I will never forget the power of that moment.

Hold On to Each Other

RABBI BENTZION KLATZKO

Senior manager, Olami North America

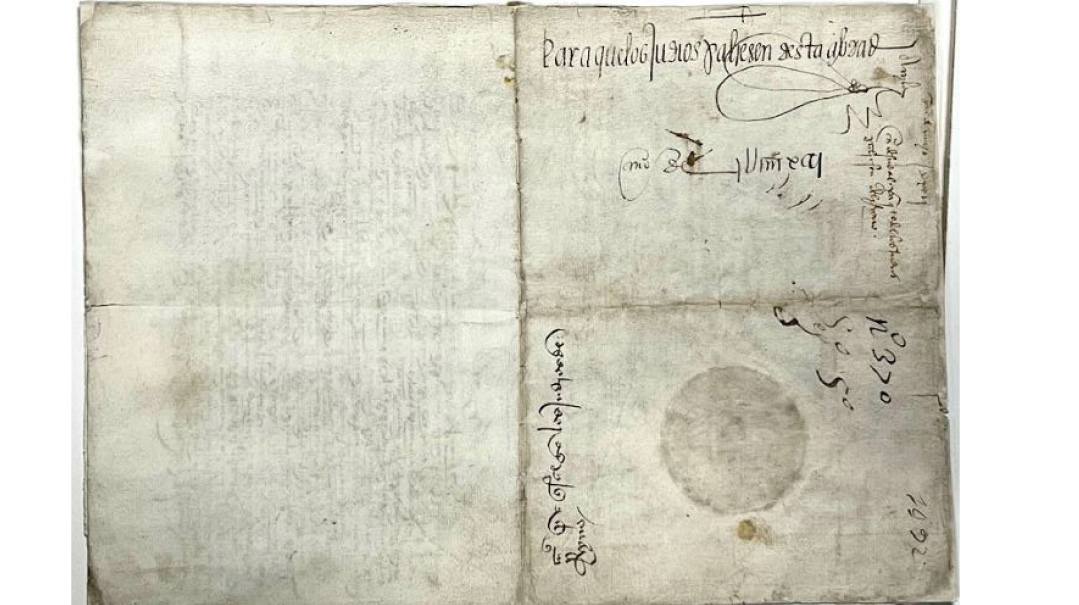

I was on a tour of Spain with an Olami Akiva group of students who were studying in a foreign-student program at IDC Herzliya. The students were non-religious, having come from all over the United States, South Africa, and other places. We were in a small city in Spain, where due to high-level connections with Spanish government officials, we had been able to arrange to view the original Inquisition edicts signed by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella. In the spring of 1492, on the urging of the evil Tomás de Torquemada, this royal couple decided to consolidate the authority of the Roman Catholic Spanish Empire by ridding it of Jewish-influenced “heresy.” All Jews were expelled from their kingdoms unless they embraced Christianity. Much of the community left Spain, going into exile on Tishah B’Aav, while those who remained would suffer the horrific brutality of the Inquisition. Ferdinand and Isabella’s malevolent tactics were later imitated in Portugal and Italy and had ripple effects across centuries of European anti-Semitism.

The Spanish press was there, as our Jewish group was shown the edict that set all this in motion. The document was taken out and displayed for us, and the students were absolutely silent. A minute later, we took out a little speaker that we had with us, and played Shwekey’s song, “We Are a Miracle.” “We are a miracle / We were chosen with love / And embraced from above… Through it all we remain / Who can explain….”

The students made a circle and we sang — sang of how they tried to destroy us with power and brutality, but here we are. We are indeed a miracle.

On another Olami Akiva trip this winter, I took a group of non-religious students around Poland. At the time, I had torn a tendon in my foot, which made walking difficult, but I had decided to do the trip anyway, which I managed by wearing open sandals, giving my foot the space it needed despite the cold.

We were in Lizhensk, at the kever of the Noam Elimelech on his yahrtzeit. Obviously, I wanted that to be a positive experience for them, but some of the students complained that they felt a little pushed and squashed at the kever. True, the kever was full, but it was lively and geshmak, there was music and food, and my students were enjoying the buffet. It bothered me that instead of seeing the ahavah and generosity, some of them only noticed that they were pushed.

Not long afterward, we went to Auschwitz. We planned the visit, as we usually do, at the end of the day, so we were among the last people in and the last people out. I took the group to the gas chambers and crematoria, which are located all the way at the end of the camp (the Nazis didn’t want the Jewish prisoners to see them upon arrival). Next to the chambers are huge pits, still full of the unburied ashes of our bubbes and zeides, even after almost 80 years.

At the end of the visit, we walked back from the gas chambers, a very long walk through the camp to the exit. We linked our arms to make a human chain, and as we walked in the gathering darkness, we sang again and again the chorus of Shwekey’s English song, “Shema Yisrael” — “Shema, Shema Yisrael / Know that there is but one G-d above / When you feel pain, when you rejoice / Know how He longs to hear your voice / Hashem Elokeinu, Hashem Echad….”

That night, it was dark and freezing, and it had been raining. The potholes of Auschwitz were full of icy water, and I noticed that the way our chain was walking, I was the one who would step into a pothole in our path. I thought of breaking hands to swerve and avoid it, but then I thought of the Auschwitz Jews who held on to each other and supported each other through the terrors, and I kept holding on to the chain.

“Rabbi, let go of the chain and walk around the pothole,” the students near me said. But I used it as symbolism, telling them, “We hold onto each other, even in difficulty.” And into the icy puddle I went, sandals and all, singing that Hashem is One. Later, I spoke about it — the message is that just as G-d is one, the people He chose is One too, and we have to live with achdus. Although there are many types of Jews, we won’t survive if we break the chain with each other. And when there are religious Jews pushing at the Noam Elimelech’s kever, we have to view their positive attributes and not their deficiencies. If we disparage each other, we fall.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 970)

Oops! We could not locate your form.