He Has Me Covered

| December 30, 2025Hashem's protection started even before I was born

As told to Aliza Goldman by Zisha Goldman

L

ooking back over my life from the vantage point of more than eight decades, I see that Hashem has always had me covered. In fact, His protection started even before I was born.

My father and mother were living with my brother and sister in Jaroslaw, Poland, when the Germans and Russians invaded in September 1939. As the Germans approached Jaroslaw, my parents tried to conceive a plan to keep the family safe. There was no time to waste. In the middle of the night, they hired a wagon, loaded in my brother and sister and some basic belongings, including their sewing machines, then swiftly fled eastward to my maternal grandparents in Lvov, which had fallen under Russian occupation.

As the Nazis and Soviets divided up the spoils in Poland, my parents and grandparents tried to figure out the best way to survive. Zeide was convinced that taking Soviet citizenship would give us protection in the event the Germans moved further east.

“Go to the consulate and get citizenship for the family,” he directed his son-in-law. “If the Germans come here, they will take the refugees, but they won’t dare start up with those who are citizens of the Soviet Union.”

Dutifully, my father set out for the Soviet consulate. He returned home that evening empty-handed, with an astonishing story: His late mother appeared before him at the consulate and prevented him from going in.

“She slapped me across the face,” he recounted in a daze. “She yelled at me in Yiddish, ‘Go away from here and don’t come back.’ ”

“What kind of nonsense is that?” Zeide replied. “Your mother is in the Olam HaEmes. Tomorrow you must go back there and get us Russian citizenship. It’s our only ticket to our survival.”

The next day, my father again headed to the consulate. He later reported that he was waiting his turn to go in when his mother appeared once more.

“I told you not to come back here!” she yelled, and this time she pushed him so hard he tumbled down the stairs.

“I’m not going back there,” my father declared, bruised and shaken, when he returned to Zeide’s house.

His in-laws implored him to go back again, but he would not change his mind.He and my mother talked late into the night. They decided that this strange encounter with his deceased mother could not be ignored — but it also seemed unwise to stay in Lvov as refugees. The extreme poverty and religious persecution in the Soviet Union paled in comparison to the German threat. So my parents decided to flee eastward.

Not wasting any time, they informed the family of their decision, gathered the children and their meager belongings, and headed to the train station. My mother bribed an agent to acquire tickets on the next train. As it turned out, this was the last train to make it into the Soviet Union from occupied Poland.

At the border, the train was boarded by Soviet troops conducting an inspection. They quickly spotted an industrial-strength Singer sewing machine among the baggage on the train.

“Whose is this?” they demanded.

My father stepped forward to claim it. There followed an interrogation. When my father revealed that he was a shoemaker, producing leather uppers, he was told he would be put to work for the Red Army making military boots.

Because my family were Polish citizens, however, they were suspected of being spies. So the army sent them further east, deeper into Russia, away from the front lines. This turned out to be Providential; when the Nazis reneged on their agreement with Stalin, they swept through the rest of Poland and stormed into Russia as well. As far as I know, none of the family that stayed in Lvov survived. Bubby’s otherworldly warning saved my family.

My father was a skillful shoemaker, and in the course of producing his quota of uppers for army boots, he was able to meticulously cut the sheets of leather in such a way that left him with leather to spare. My parents used this excess to make leather shoes and sandals that they sold on the black market.

Not that they were prospering. Starvation was a constant and ever-present enemy — to the point that when my mother showed up at the hospital in the spring of 1944/5704 to deliver me, the hospital staff didn’t believe she was expecting.

“You don’t look like you’re carrying a full-term baby,” they insisted.

My mother somehow persuaded them to admit her. My subsequent appearance on the scene proved her side of the story to be correct. Despite my mother’s privation during the pregnancy, baruch Hashem, here I am more than 80 years later to share the tale.

Mindful of his mother’s warning against Soviet citizenship, my father somehow obtained a birth certificate for me showing a different country of birth. The next hurdle was finding a mohel.

After a very cautious search, my father was able to locate an old mohel who was still practicing in a faraway town. Once my mother and I were deemed strong enough for the journey, we three set out early one morning.

“Stay inside the house, and don’t let anyone know that you’re home,” Mother instructed my older siblings, all of nine and seven at the time. She dared not tell them where we were going. Milah was dangerous for all those involved.

The long journey included hours on the train. To add to the stress of this covert operation, Mother was very concerned when she saw the shaking hands of the old mohel. But because there really was no other option, she reluctantly handed me over.

Meanwhile, around that same time, half a world away, a middle-aged Jewish husband and father in Brooklyn read a report about the emerging truth of the Holocaust. When he shared this terrible news with his wife, they cried together about the need to bring Jewish neshamos into the world to make up for all the ones taken by Hitler yemach shemo. Hashem heard their sincere desire and blessed them with a baby girl.

IT was not long after this that the long-awaited news arrived of the Germans’ final defeat. The war was finally over. And because my family did not have Soviet citizenship — thanks to my paternal grandmother’s intervention — we were able to leave Russia.

We first returned to Jaroslaw, Poland, in the hopes of recovering our home. Our former neighbors were unpleasantly surprised to see us. Having already taken possession of our house, they threatened violence if my parents tried to go to the authorities.

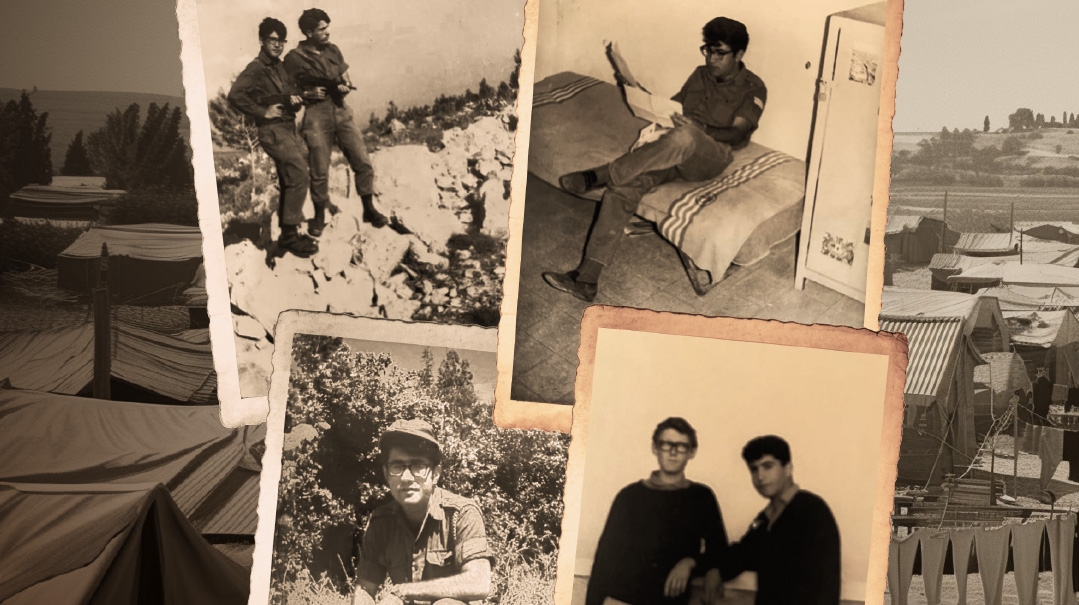

Our next stop was a displaced persons camp in Germany. My parents chose to stay in the section administered by the United States, in a former army barracks. We slept on the bunk beds. We children had no toys, so the popular game was to play soldier. Any stick worked as a gun, and we imitated the soldiers we saw around the camp.

My father worked on getting the necessary paperwork to allow us entry into the US. He sent letters to relatives asking them to sponsor our family. We waited and waited for a positive response. It took several years. I was already attending kindergarten when my father finally heard from his Uncle Z., who agreed to be our sponsor.

In 1949, we boarded the USS General Haan, a military transport ship that brought many war survivors to the US. We landed in New York. Uncle Z. met us at the dock and took us to the bungalow he had rented for us on Coney Island, near where he lived.

My parents found employment in the garment industry. My mother worked as a finisher. Once again, the sewing machines, which had journeyed with us across the ocean, came into play. Under the table, my mother was allowed to bring some garments home to finish in the evenings. This allowed her to earn some urgently needed extra money.

As summer turned to fall, my parents searched desperately for a real apartment. There was no heat in the bungalow we were in, as it had been built to accommodate the summer crowd, who came to be near the beach. Finding an ad for an apartment in Brownsville, my parents were grateful to discover that the owner, Mr. M., was from Poland, and they could easily communicate our dire circumstances to him. Although another family had wanted the apartment, Mr. M. gave it to us.

“These people have nowhere to be for the winter,” Mr. M told the other prospective tenants, “so I must give them priority.”

I have never forgotten the kindness of that Polish landlord. Now that I’m a landlord myself, I try to treat my tenants with the same fairness and understanding.

After we moved to Brownsville, my parents enrolled me in the local public school, PS 175. But I was a refugee child from Europe who spoke no English. I would come home from school and tell my mother, “I have no idea what my teachers are talking about.”

As my parents integrated into the neighborhood, they found out about Chaim Berlin elementary school on Prospect Place and enrolled me there. (This school was not affiliated with the Chaim Berlin yeshivah.)

The school served both American-born and refugee students. The teachers gave in-class assignments to the English-speakers and then worked closely with the rest of us to help us learn the language. These teachers’ patience, caring, and dedication stayed with me. I myself later had the opportunity to teach, and I hope I instilled the same feelings in my students.

Rabbi Portnoy, who ran the school, had fled to Shanghai with the Mirrer Yeshivah. He was an exceptional man and took especially good care of the immigrant children. For example, every year before the Yamim Tovim, a group of boys from less well-off families (which included me) would be called down to the lunchroom. We had measurements taken and were presented shortly thereafter with new sets of clothing.

Rabbi Portnoy made frequent appeals in Yiddish on the radio to raise funds for his school. He also formed a choir of schoolboys who performed on the radio. I was selected to be part of this group and had my first opportunity to sing professionally. (In the years since then, I have performed in many more choirs, including a recent performance at Jerusalem’s Binyanei Ha’umah. I also learned nusach hatefillah and served as the Yamim Noraim chazzan in various shuls.)

MY parents worked hard and saved scrupulously all the years I was growing up in Brownsville. That became important as the neighborhood began to decline. By the time I was in night college, I had to be very alert on my way home for empty bottles thrown my way. I was once chased by a fellow with a baseball bat. Then, when my father was beaten up one day, my parents knew the time had come to move.

With their painstakingly acquired savings, they purchased a multifamily home on the outskirts of Boro Park. One of the apartments had been converted to a store. My parents left the garment industry and learned to run the store. Eventually, they converted it back into an apartment, and the rental income was sufficient to cover their needs. My parents lived out the rest of their lives in that home.

Years after we had moved on, I ran into an old elementary school classmate. He seemed so broken. He had been at the head of the class; he excelled in Hebrew and English, and he was even the best at sports. He lived with his mother, and she did not have the money to pay for yeshivah high school. He was not offered a scholarship, so he went to the local public high school. When I met him, he was a shadow of his former self. I’ve always thought it was because he did not have the opportunity to attend a mesivta. I imagine that my passion for supporting the Shuvu schools, under the encouragement of Rav Pam ztz”l, was due to this encounter.

As a young adult in Boro Park, I davened in a Young Israel shul. There I was introduced to a young lady, who turned out to have been the baby girl born to that middle-aged Brooklyn couple pained by the plight of Yidden in Europe. A little over two decades after their heartfelt desire to bring another neshamah into this world was answered, they were zocheh to walk her to the chuppah, where she circled me as we began our own Jewish home. It wasn’t long before we too were blessed with a baby of our own, with the birth of our bechor.

I was now not only a married man, but also a father. My wife, who had been working while I finished graduate school, was on maternity leave. I had to provide parnassah for my family.

In the late ’60s, the six-day workweek was no longer a problem for frum Yidden, but there was still plenty of anti-Semitism in the workplace. Not wanting to limit my chances at getting my first job, I purchased a toupee (basically a yarmulke covered with hair) to wear on interviews. Fortunately I soon landed a job as a computer programmer for a well-known company.

During my first year on the job, I was sent to a computer course for employees in Lowell, Massachusetts. The training lasted several days, so the company put us up in a local motel. In those days, they assigned two employees to each room. My roommate turned out to be a Canadian.

I was apprehensive about davening in front of this fellow. Was I not wearing a toupee to help hide my Jewishness? How would this guy react if he saw me in tallis and tefillin? I made sure to wake up very early and silently don my tefillin and tallis. I stood in a corner and tried to be as quiet as possible.

I was in middle of Shemoneh Esreh when I heard a gasp. I turned to see that my roommate had awoken. He was gaping at me, as I stood there wrapped in my tallis and tefillin, with a look of absolute horror. He began to shake uncontrollably and quickly dove under his covers.

When I finished davening, he was still cowering under his bedding, unable to pull himself together. I walked over to try to talk to him. He mumbled something about the devil, Jews, and removable horns.

What! He thinks I’m the devil? I was somewhat disconcerted.

He continued to shake under his covers and resisted any explanations I offered. Unable to help him, I informed the head of the program that my roommate seemed to be under the weather. I did not explain that his illness was a reaction to having observed my prayer rituals. As my roommate was in no shape to explain, the story remained untold. It was determined that he needed to be sent home to recover. Being in no condition to fly home on a plane, the program director found an alternate method of transportation for the fellow.

During my fifth year at the company, I was assigned a new client. I would be working primarily in their offices to set up their computer system. One day, after a few months on the job, I noticed an obviously frum fellow. He’s wearing a yarmulke! I noted in surprise. Maybe I can also switch to a yarmulke, I decided. It isn’t as risky as when I was looking for my first job. Not wanting to take too big a risk, I spoke to the manager of the client company.

“Sure, you can wear a yarmulke, if you want,” he graciously answered.

It felt so right to be donning a yarmulke instead of the toupee. Everything went smoothly for a couple of weeks as I worked in the client’s offices. Then one day my boss came from my company for a visit.

“What’s with the beanie on your head?” were his first words upon seeing me.

Uh-oh! Now I’m in for it. A sense of unease accompanied me throughout the day.

My fears were not unfounded. That Friday I was called into my supervisor’s office.

“The company isn’t doing so well and we need to downsize,” I was told. “You drew the short straw.”

Just like that, I was dismissed, with a few months of severance pay.

It was a challenge not to second-guess my decision to wear a conspicuous head covering. How will we manage until I find a new job? I worried. Also, this happened during June, just before I had to meet with the registrar of my boys’ yeshivah to discuss the coming year’s tuition payments. What would I tell him?

As it turned out, the registrar was very understanding. “We’ll leave the tuition at the same rate as last year. If you can’t meet the payments, don’t worry. Just do the best you can.”

I’d like to believe that the registrar’s success in business after moving on from his position was a reward in this world for the sensitivity and understanding he showed all the parents like me.

The very next week I received a call from the City of New York personnel department. I had applied the year before for a civil service position and never heard back from them. The deputy commissioner of a city agency had now found my name on a list and called to offer me a job. I proudly donned my yarmulke for the interview.

I worked for the City until my retirement 25 years later.

As I reflect on my life and my family’s escape from the Germans before I was born, I see that Hashem truly had me covered, every step of the way. I realize that all our choices in life, past and present, are tests sent directly from Above. The key to making the right decision is to follow Hashem’s direction. This will make you worthy of continued protection.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1093)

Oops! We could not locate your form.