He Gave Us the Tools

A Tribute to Rabbi Dr. Avraham Yehoshua Twerski

Three weeks ago, Rabbi Avraham Yehoshua Twerski moved out of his Jerusalem home when his wife contracted COVID-19. But when he tested positive one week later, he felt that there was no point in not being at home; the couple were both suffering from the same contagious disease.

In the car ride back to Jerusalem, Rabbi Twerski related to his devoted stepson, Rabbi Danny Myers, a story — the last story that he would tell.

Relating this anecdote takes on extra significance concerning an individual who knew how to harness the power of a story to convey life’s deepest lessons.

Why was he so successful with his stories? A story.

When Eliezer was dispatched to find a wife for Yitzchak, he saw that the well water rose miraculously for her. But Eliezer reserved his judgment and waited to see if Rivka would fetch water for himself and his camels.

Why, Rabbi Twerski asked in the name of Reb Chaskel of Kuzmir, wasn’t it enough to see the water rise? Such a miracle should have been a clear sign that Rivkah was the designated wife for Yitzchak. Answered Reb Chaskel, “One good deed is worth a thousand miracles — Eliezer was not impressed by miracles; he wanted to see character.

Only such stories would Rabbi Twerski relate. The ones whose teachings may be applied to our own lives so that they are not just stories, but lessons.

“There was a rabbi in a far-off town,” Rabbi Twerski told Rabbi Myers in that fateful car ride, “who tried to encourage the town folk to observe mitzvos. It was an uphill struggle, but one day a villager informed the rabbi that he had started to keep kosher. The rabbi was elated and saw an opportunity. ‘Maybe the time has come to begin observing the Sabbath?’ he pressed.

“ ‘Don’t be a chazer,’ snapped the indignant townsman.”

Rabbi Myers was bemused. The story seemed incomplete and lacked a happy ending. But Rabbi Dr. Twerski, whose lifetime of influence and 60-plus published works impacted upon an entire generation, was not about to let the curtain down before exiting with gratitude.

“I will not be a chazer,” he declared, “and claim that I did not derive enough from life. I am 90 years old and received far more blessings than I deserved. My father and several siblings died young. I have so much to be thankful for.”

Rabbi Twerski, a medical doctor, knew where he was headed with COVID-19, and although it would claim his life, he would not allow it to claim his dignity. Life and dignity may be the two most paramount aspects of Rabbi Twerski’s blessed years.

Deprived of the advantage of time to reflect — I am typing these words but half an hour from returning from Rabbi Twerski’s midnight funeral in Beit Shemesh — I trust I have gotten this right.

At his funeral, upon his request, there were no eulogies. All he asked was that he be laid in the grave to the melody that he composed in 1960, “Hoshia es amecha u’vareich es nachalasecha, u’reim v’naseim adolam — Save Your People, and bless Your inheritance and shepherd them and elevate them forever.” How absolutely fitting that this luminary — the one who made recovery from addiction kosher for the religious world, saving untold lives in the most literal sense, and was a blessing for tens of thousands through his uplifting, life-changing works — would be laid to rest with a song sung by the attendees, with a catch in their voices and their eyes swimming, requesting that the Almighty raise His People.

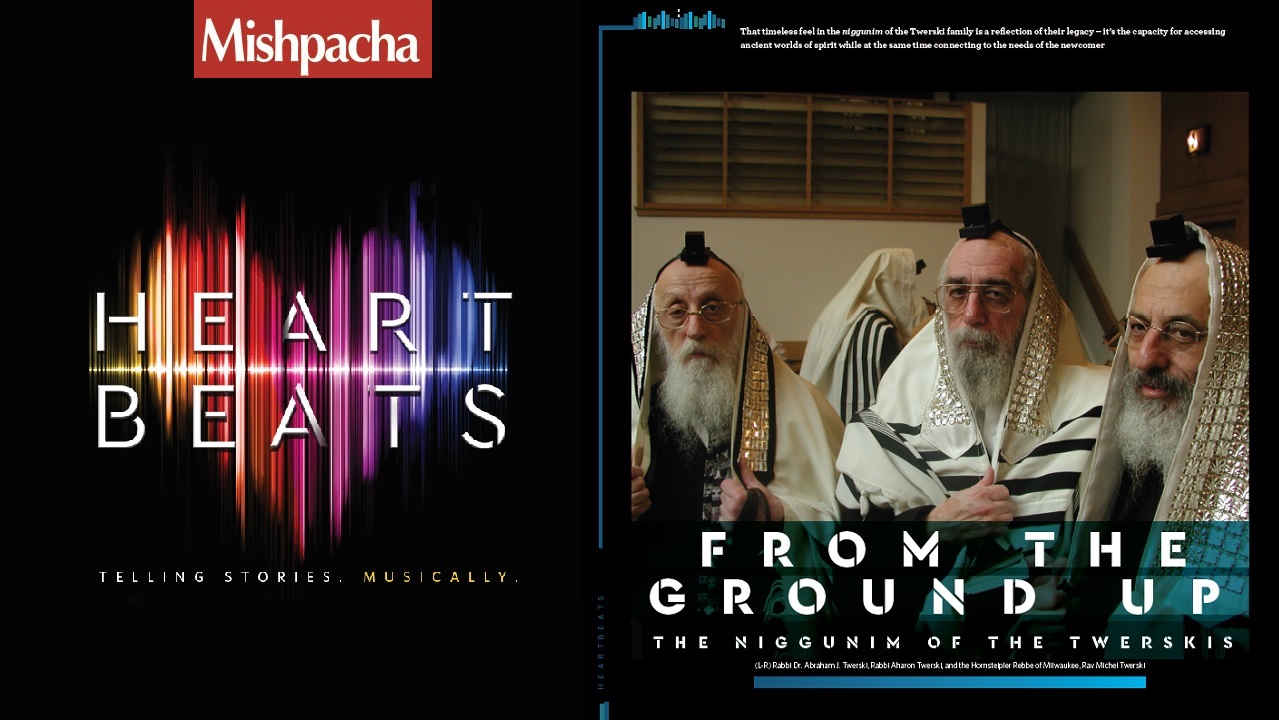

LISTEN: Songs of the Twersky Dynasty

Rabbi Twerski was very proud of his chassidic background and every aspect of his being was the life of a chassid, both as it is contemporaneously understood, as well as in the Talmudic definition of a pious individual. Born in 1930, he was a scion of the Bobov and Chernobyl dynasties, an accomplished scholar and ordained rabbi who completed medical school and then trained as a psychiatrist. He achieved great distinction in that world, serving as head of the psychiatry department in Pittsburgh’s St. Francis Hospital and founding the Gateway Rehabilitation Center.

The Orthodox community of Pittsburgh in the 1960s and ’70s was small and very united. All homes were open to one another and the boys and men even played softball together on Sundays (although Rabbi Twerski confessed that he wasn’t the best of athletes).

Although Rabbi Twerski had a fond nickname for everyone, the small religious community referred to the celebrated psychiatrist simply as “Reb Shia.” And when the local religious Jews observed guests who had come from Boro Park or Monsey for treatment and understood precisely what these individuals, not quite attired for the Midwest, were doing in town for weeks, they labeled them “The Shiites” — a clever tribute to the healing powers of their “Reb Shia.”

Rabbi Dr. Twerski was revered even outside of Pittsburgh’s religious community as an unmatched scholar. Once, during their yearly pilgrimage to Israel, a group of loosely affiliated Jews from the neighboring McKeesport saw that regard come to life.

Every trip always has one individual that makes it memorable, one way or another. In this instance the trip was graced by a bespectacled elderly man whose breast pockets were adorned with pocket protectors. The fellow, who considered himself an expert on all of the holy sites, barely allowed the tour guide to get a word in edgewise. On every matter the septuagenarian would hold forth describing his expertise to an uninterested audience.

When the bus neared the Rambam’s grave in Teveria, some of the passengers were curious as to who exactly was this sage. Mr. Know-It-All dismissed their queries with a simple, “He was like Twerski.”

But perhaps Rabbi Twerski’s greatest achievement was unlocking the world of psychiatric insight for the Orthodox Jew. With his chassidic background, rabbinic ordination, heimish air, and treasure trove of chassidic tales, Rabbi Dr. Twerski was able to serve as a rare bridge between two worlds. He introduced frum Jews struggling with addiction to the Twelve Steps and gave them the keys to recovery. He shared insights into the human psyche and the work of self-improvement in a warm, witty voice that was always encouraging and thought-provoking and never threatening or distant. He was a fearless trailblazer as well, founding the Gateway Rehabilitation Center in Pittsburgh and the Shaar Hatikvah rehabilitation center for prisoners in Israel. He showed struggling Jews that one can benefit from the advances of psychology while never compromising their observance.

When I interviewed Rabbi Twerski for my film about Reb Elimelech M’Lizhensk ,he spoke without notes and was flawless on the first take. Experienced actors cannot achieve this. But when Rabbi Twerski spoke about chassidic giants, it was the truth pouring out of his heart — with passion, faith, and conviction.

My son was privileged to learn with Rabbi Twerski every Friday for the last few years. This bochur has learned in the finest Lithuanian yeshivos, cultivating zero connection to the chassidic movement, other than becoming a chassid of Rabbi Twerski. Prior to my son’s wedding this past summer, frail Rabbi Twerski, confined to a wheelchair, affirmed that he would — unbelievably — attend. Our joy knew no bounds, until his doctor absolutely forbade such an excursion in the midst of a pandemic.

The dozens of emails I have received from Rabbi Twerski over the years are all signed with startling humility: “Twerski.” Apologizing that he would not be able to attend the wedding after all, a very remorseful mentsh signed his full name.

Rabbi Twerski was faithful to tradition, yet he knew how to integrate modern advances from the world at large. He saw great wisdom in the Twelve Steps program for recovery from addiction, and was pleased when someone taped up a sign in his Gateway Rehabilitation Center in Pittsburgh: “The elevator is broken, you must take the 12 steps.”

Rabbi Twerski retained an amazing energy and openness to learning new things throughout his long life. He would learn from anyone, fulfilling the Mishnaic dictum for wisdom, “A smart man learns from anyone.” Indeed, he claimed that he gained great insight from one of his recovering addicts as to how harmful it is to bear a grudge. As he put it, bearing a grudge is allowing your enemy to live in your most expensive real estate (your mind) rent-free.

Culling knowledge from wherever it was available, he employed a system that mended the shattered, restored families, and saved lives. As a psychiatrist he understood the toxic effect of low self-esteem and created a library of literature that enabled countless individuals to achieve their potential and hone their abilities.

Rabbi Twerski had a great affinity for the Peanuts cartoon strip, for it was, like effective recovery, simple and direct. In one memorable strip, Charlie Brown scolded Lucy for handing out to her friends lists of their faults. Lucy justified her behavior by maintaining that she wanted to make the world a better place for herself to live in. Rabbi Twerski’s take on the clever cartoon was that we know what is wrong with others, but we neglect to correct our own faults.

In other written works, he emphasized the importance of self-esteem and respecting one’s inherent worth. He had an amazingly insightful read on the human condition and an equally amazing storehouse of knowledge to inspire and elevate striving human beings.

He spent his long life healing, publishing, and offering others the ability to raise themselves higher than their broken circumstances, giving them both a vision of what they could be and the tools to get there. And when his own time came he left with a song: a plea for salvation, but also a paean of appreciation for nine decades of blessing.

Rabbi Hanoch Teller is launching a new podcast this week entitled, “Teller From Jerusalem,” available on all platforms, or look for www.tellerfromjerusalem.com

No Fear

I read Rabbi Twerski’s book Dearer Than Life — Making Your Life More Meaningful during my first year of medical school. It helped me reconsider what true avodas Hashem and mesirus nefesh really means, and taught me how to align myself with Hashem’s will right from the start of my career as a physician. In fact, I found tremendous inspiration in the dozens of titles he penned, as he brought Chazal’s wisdom to the medical community and mainstreamed the life-saving science of psychiatry into the Torah-observant world.

I met Rabbi Twerski for the first time during my psychiatry residency, and in my excitement, I impulsively blurted out, “I’m so excited to be a frum psychiatrist just like you!” Rabbi Twerski smiled back, patted me on the shoulder, and in his inimitable grace, told me, “We’re excited to have you, too.”

It was quite a few years later when we met again at his home in Jerusalem. The Rav’s octogenarian body was confined to a wheelchair but his neshamah remained light as could be. I came to discuss some public health initiatives, to which he encouragingly responded how “a lobster only knows to grow a new shell when it feels the stress of its old one getting too tight.” In other words, we can only truly develop when we’re under pressure, and now, he felt, the time was right.

I sought his advice again, when I was planning to give a talk in a town that had tragically experienced the loss of several bochurim to suicide. I needed an eitzah, and he was clear that the most important thing to get across were the honest facts. “When I spoke up about domestic violence in our community, I received death threats and they needed to organize security guards for me,” he told me. “That meant that I was really on to something — don’t be afraid to tell the truth!”

Within mere hours of his passing, I received messages from patients, colleagues, and friends sharing their own stories. One man told me how Rabbi Twerski, a giant in the field of addiction, coached him through his first year of sobriety. Another told me how the Rav had called to give him chizuk after he relapsed and was headed off to a detox facility. Both are sober decades later, and while Rabbi Twerski would connect it with their dedication to Alcoholics Anonymous, they attributed their success to the Rav’s brachah and dedication to saving their lives.

The last time I spoke with Rabbi Twerski was to discuss a new project I’d launched: a kids’ book aimed at explaining mental health for children with family members experiencing psychiatric illness. Rabbi Twerski told me, “If we aren’t making this kind of thing happen, I don’t know who will.”

Rabbi Twerski — gifted psychiatrist, talmid chacham, and human being supremely dedicated to helping one person at a time to achieve their full potential — lived his life aligned with the mesirus nefesh he taught me as a young med student.

In his merit, let’s all step up to the plate.

— Dr. Jacob L. Freedman

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 847)

Oops! We could not locate your form.