He Empowered a Generation

| June 28, 2022On his sheloshim, a tribute to Rabbi Pinchas Stolper, the man who made generations frum

H

avdalah. In most Torah-observant Jewish homes, that’s the time when the inspiration of Shabbos dwindles down. But at regional shabbatons and especially at the end-of-the-year NCSY National Conventions (“National,” as the kids would call it), Havdalah was when the inspiration was just getting started. Rabbi Pinchas Stolper, longtime visionary of NCSY, a national teshuvah movement, would call the Havdalah process “ebbing,” referring to how Shabbos was slowly ebbing away, the last chance to absorb its holiness. He would ask a teenager to hold the Havdalah candle and would then begin. As Rabbi Stolper put it, “Havdalah usually lasts for three minutes, but in NCSY it would go on for three hours.” It was at that time, in a pitch-black ballroom, when an unaffiliated teenager from Nebraska would feel the beauty of Shabbos and learn what it means to be a soldier in Hashem’s Army.

The success of NCSY, where thousands of young people over the decades discovered and strengthened their Yiddishkeit, can be attributed to one person: Rabbi Pinchas Stolper ztz”l, who was niftar last month at the age of 90. Back in 1959, when Pinchas Stolper took over the reins of a near-defunct NCSY, he was a true pioneer of the teshuvah movement, and in fact it was he who coined that phrase in a 1963 article in the Orthodox Union’s Jewish Life magazine, to describe what was to many at the time a surprising growth of a strictly halachic youth movement for public school kids.

How was Rabbi Stolper able to create a teshuvah movement in America in the 1950s and ‘60s when all others had given up on Jewish youth? And what was his secret of success in setting a halachic standard and having the confidence that his charges would rise to the challenge, instead of bending or compromising in order to attract the crowds — an ongoing debate in kiruv until today?

Training Ground

Rabbi Pinchas Stolper was born in Brooklyn, New York, on October 22, 1931, to Rabbi Dovid Dov (Bernard) and Nettie Stolper. Dovid Dov’s family originated from the Lithuanian town of Eisheshok, walking distance from Radin. By the 1880s, all four of Rabbi Stolper’s grandparents had immigrated to America, where Dovid Dov was born in 1906. Rabbi Dovid Dov Stolper, a natural orator and leader, was drawn to the rabbinate. His speeches were filled with passion, excitement, and idealism, and he was one of the first American Jewish leaders to publicly condemn the emerging horrors of the Holocaust.

“I was just a little boy, but those speeches influenced me,” Rabbi Stolper told Mishpacha’s Eytan Kobre in a wide-ranging interview in 2013. He said his most vivid childhood memory was that of his father sitting in front of the radio crying, as he listened to reports of the Nazi atrocities after the Germans invaded Poland in 1939.

When Pinchas was five years old, his father gave up his rabbinical position in Montclair, New Jersey, and moved his family to East Flatbush, Brooklyn, in order for Pinchas to attend the Yeshiva of Flatbush, where he studied through eighth grade. After that, his best option seemed to be to enroll in Tilden Public High School, which was near his home. But that summer, Pinchas noticed an ad in his grandfather’s Yiddish newspaper, the Morgen Journal, which announced that Yeshiva University was opening a new yeshivah high school, the Brooklyn Talmudical Academy (BTA). He showed the ad to his father, who agreed that it was definitely a better choice than Tilden.

It was during Pinchas’s time in BTA that he first became interested in Betar, the Zionist Revisionist youth movement founded in 1923 by Zev Jabotinsky. It happened when Pinchas was walking down Pitkin Avenue, which was then the main Jewish shopping strip in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, and he noticed a young fellow handing out a magazine called Hadar, Betar’s publication. Pinchas read it from cover to cover, and he was hooked. It was 1945, right after the Holocaust, and the thirst for a Jewish State was in the air. Pinchas, growing up with his father’s steadfast commitment to Eretz Yisrael, eagerly joined.

In those days, Betar had several hundred members, most of them in the New York area. Before long, 16-year-old Pinchas was appointed leader of the Crown Heights chapter and soon after was promoted to Director of Education. Little did he know at the time, but Betar became a training ground for Pinchas, giving him practical knowledge and experience in all aspects of running a successful organization while sticking to his principles — invaluable skills would serve him well when, years later, he would develop NCSY into an effective national youth and kiruv movement. At the time, Betar’s national head was Moshe Arens, a natural leader with a scientific mind, who eventually became Israel’s Minister of Defense and Minister of Foreign Affairs, as well as Israel’s ambassador to the United States. A year after Pinchas joined Betar, Arens announced his plans to make aliyah and convinced Pinchas, who was just 18, to run in the elections to replace him as the new head. Pinchas agreed and won a tough race against another future prominent fellow named Meir Kahane, his classmate in Yeshiva of Flatbush and BTA.

But little did Pinchas know that his involvement in Betar would lead him to become a student of Chaim Berlin and one of the closest talmidim of Rav Yitzchok Hutner.

In 1947, Pinchas was walking in East Flatbush when he chanced upon Rav Avigdor Miller, who at the time was the mashgiach ruchani at Chaim Berlin. Realizing that Rav Miller was a gifted speaker, Pinchas asked if Rabbi Miller would be interested in serving as the rabbi of the shul where he davened, the Young Israel of Rugby, which needed a rav. After Rav Miller answered in the affirmative, Pinchas mentioned his name to the shul’s president, and within a few weeks, Rav Avigdor Miller became the new rav. Since then, Rav Miller and Pinchas became close friends, and years later, Rav Miller told Rabbi Stolper’s son, Rabbi Akiva Stolper, “I have a great deal of gratitude to your father. He’s the one who encouraged me to write my books.”

One Shabbos in 1950, Rav Miller, seemingly out of the blue, casually asked Pinchas if he’d be interested in meeting Chaim Berlin Rosh Yeshivah Rav Yitzchok Hutner. Pinchas eagerly agreed, and that meeting soon led to Pinchas becoming a full-time student in Chaim Berlin. Only many years later did Rabbi Stolper discover that it was, in fact, Rav Hutner who had requested the original meeting.

At the time, the mayor of New York City, Vincent Impellitteri, had invited a visiting German soccer team for a reception at City Hall. The Betar leadership saw this as an insensitive affront to the Jews of New York who were still reeling from the trauma of the Holocaust, and as head of the organization, Pinchas arranged a protest by storming City Hall and throwing rotten tomatoes at the mayor, his entourage, and his German guests. Pinchas was promptly arrested, and the picture of the arrest made the front page of every newspaper in New York and beyond. Someone brought the Daily Mirror, which had a picture of Pinchas clad in his suit and hat, to Rav Hutner’s attention. Rav Hutner summoned his talmid, Chaim Feuerman [the future Rabbi Dr. Feurman a”h, a well-known educator] and asked, “Ver iz der Stolper? Der yungerman hut chutzpah un mir darfen em hoben [Who is this Stolper? This young man has chutzpah and we need to have him]!” That incident propelled Rav Miller, who was the mashgiach in the yeshivah, to invite Pinchas to meet Rav Hutner, thus forming their lifelong relationship.

Keeping the Spirit

In 1955, Pinchas married Elaine Liebman of Rock Island, Illinois, a western town on the Mississippi River. The Jewish education that was available in Rock Island was negligible, and it became clear to Elaine’s father that it would be best for her to go to New York for a more advanced education after high school. Elaine took a part-time job teaching at a Talmud Torah on Long Island, and would travel on the Long Island Railroad to get to work. One day, she struck up a conversation with a man by the name of Mottel Kreiner, after overhearing him mention that he was making aliyah. Elaine asked him incredulously, “What do you have to do with aliyah? You aren’t even shomer Shabbos!” Mottel realized that this passionate young lady might be a good idea for his friend Pinchas Stolper, whom he knew from Betar (they were even arrested together at the protest at City Hall).

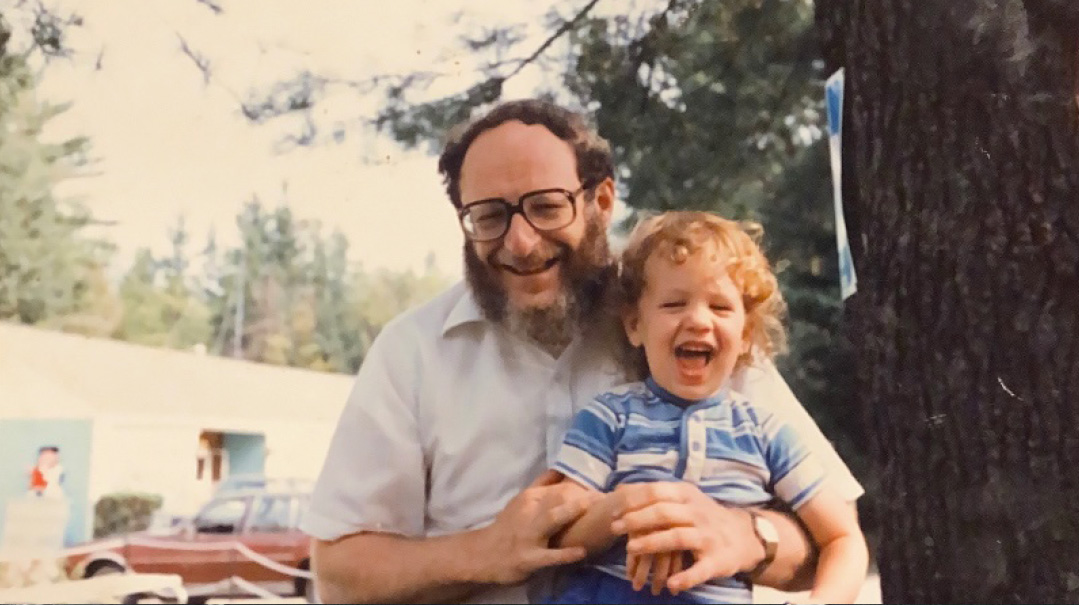

Rabbi Stolper often said that without his wife’s support and encouragement during NCSY’s formative years, he would never have been able to turn it into the driving force behind the teshuvah movement revolution. Rabbi Stolper would sometimes be away from home for six weekends in a row, traveling to Shabbatons around the country. His son Reb Akiva says he remembers being confused when his father would actually make Kiddush at home, assuming that was his mother’s job.

In September 1956, Rabbi Stolper accepted a position as director of Young Judea’s Long Island Region. Young Judea was a Zionist youth movement, and although its national director at the time was Amram Prero, a reform rabbi, he never interfered with the way Rabbi Stolper ran the region. There were no active Orthodox youth movements on Long Island, so Pinchas’s job was to have Young Judea serve the youth of all the synagogues —Orthodox, Conservative and Reform, which created obvious difficulties.

One major challenge was mixed dancing, which was a routine part of social events for Jewish youth in those days. He knew that if he tried to invoke halachah as the basis of his objections to social dancing, he wouldn’t get anywhere, so instead, he talked about the Zionist spirit of the organization, arguing that the organization should only have chalutz [Israeli style] dancing, which was done in separate circles. The youth commission agreed — on condition that Rabbi Stolper would have to convince the kids. He did. As a result, at a time when almost all Jewish youth groups were holding mixed dances, the religiously neutral Young Judea of Long Island, under Pinchas Stolper, wasn’t.

It wasn’t until his second year with Young Judea that he received his first phone call of complaint from an irate Amram Prero. “Why haven’t you sent any kids to Camp Tel Yehuda (Young Judea’s camp in the Catskills)?” Rabbi Stolper’s answer was simple: The camp was treif. The next year, Young Judea rebuilt the camp kitchen and hired religious staff — confirming once again Rabbi Stolper’s belief that many battles for Torah could be won by being honest and consistently sticking to one’s principles.

In between Young Judea and NCSY, Rabbi Stolper spent two years in a totally different framework. In 1957, toward the end of the second year working for Young Judea, Rav Avigdor Miller announced that he would be organizing a Melaveh Malkah for the Ponevezher Rav, Rabbi Yosef Kahaneman, who was in the US on a fundraising trip. Yet in the end, only three people attended — Rabbi Miller, the Ponevezher Rav, and Rabbi Stolper. The Ponevezher Rav took an instant liking to Rabbi Stolper, seeing in him a person of vision. After speaking for an hour, the Ponevezher Rav asked Rabbi Stolper, “Efsher vilst kumen tzu mir in yeshiva in Bnei Brak [Perhaps you would be interested in working in my yeshiva in Bnei Brak]?” Rabbi Stolper was elated to have an opportunity to fulfill his lifelong dream of living in the Holy Land. In August of 1957, Rabbi Stolper resigned his position with Young Judea and headed off to Eretz Yisrael with his young family.

Rabbi Stolper worked with the Ponevezher Rav for two years until 1959, when word came from the States that his father, Rabbi Dovid Dov, had taken ill and his family in Brooklyn desperately needed him to return home. Rabbi Stolper had no choice but to pick up his family again and head back home. Upon his return though, he realized that American Orthodox youth were in big trouble. The Conservative and Reform movements had already created youth groups, but the Orthodox community had yet to make a youth movement of its own. Something had to be done. And fast.

No Compromises

Five years before, in November of 1954, the Orthodox Union was hosting its national convention in Atlantic City. It was a time of reflection and new ideas to benefit the Orthodox community, which seemed to be teetering on the brink. A few weeks earlier, in preparation for the convention, the OU’s national secretary Harold Boxer approached Moses Feuerstein, the OU’s president, and explained how he and his wife Enid had traveled around the country and saw what assimilation and ignorance was doing to the youth. He believed that the creation of a youth movement associated with the Orthodox Union was crucial. The board agreed, and the National Conference of Synagogue Youth, NCSY, was born. It limped along for the next four years. Mr. Boxer, a forward-thinking attorney who wasn’t himself blessed with children, tried valiantly to keep the organization afloat, but it just wasn’t taking off. By June of 1959, the Orthodox Union was on the brink of dismantling NCSY. They felt that although it was an honest attempt to create an Orthodox youth movement, it clearly wasn’t meant to be.

But Harold Boxer wasn’t taking no for an answer. “Even if we try twenty times, we must still try again, we dare not give in,” he said. He implored the Board to give him one more chance to succeed. A new search was started for a suitable candidate to serve as its national director. At the time, a woman by the name of Thea Odem was working as an assistant editor of the OU’s magazine, Jewish Life. She had worked for Rabbi Stolper while he was running Young Judea, and after learning that he had recently returned to New York, mentioned his name as a candidate. Rabbi Stolper was contacted, and in September of 1959, he was appointed as NCSY’s national director with an annual salary of $7,500 plus $2,500 towards a part-time secretary. Few believed that Rabbi Stolper would be able to revive NCSY after so many failed attempts, but by 1960, only a year later, he had successfully held three dozen regional events. In 1962, he ran 60 events, and in 1964, he ran 80, with thousands of new members — teenagers from around the country whose Yiddishkeit became ignited.

Rabbi Stolper often recalled those years of austerity. He would fly in yeshivah students to run the events – talmidim from Torah Vodaath, Chaim Berlin, Telshe, Ner Israel, Chofetz Chaim, MTJ and YU, who would say that it was their gain, as they were compelled to strengthen their own knowledge of Yiddishkeit. But while there were never enough funds for full air fares, that didn’t deter Rabbi Stolper. He told the advisors to wait around at the gate until the plane was fully boarded. Back then, if there were empty seats left on the plane, students could fly for half price.

Once, in the middle of a convention, Rabbi Stolper received a message from the OU that they wouldn’t be able to continue allocating funds for NCSY’s functions and would have to severely curtail the organization’s activities. Rabbi Stolper was at a loss – he wasn’t even sure how he’d pay the hotel bill that weekend. There wasn’t much he could do except daven – and so he sat down with the kids and composed his first and only song: the famous NCSY tune to the words of “Lulei Sorasacha” (“Were it not for the sake of Your Torah, I would certainly have succumbed to my affliction”). Like so many of his challenges along the way, it was the comfort of Torah and the fact that he was helping to bring Hashem’s children closer that would pull him through.

It wasn’t just Rabbi Stolper’s theological arguments that drew kids toward Yiddishkeit. It was his deep devotion to these teenagers who were entrenched in the darkness of assimilation, and his passion to bring out their limitless potential. When he realized how little English literature there was on basic Jewish subjects, he sat down and wrote small books on various subjects – from halachos of Shabbos to Jewish dating and marriage — and handed them out at NCSY events.

In 1960, the first national convention was held in the Monsey Park Hotel in the Catskills. “National” would in the years to come become the powerful focal point of the year’s activities, sending the young people back home to their respective regions with a contagious and inspired spiritual energy.

The kids arrived from Savannah, Charleston, Peoria, and many other locations accompanied by their shul youth directors. Rabbi Stolper called over the youth directors and laid down the rules. There would be a mechitzah for davening, no mixed swimming, and no mixed dancing. The directors were not only skeptical about his seemingly radical ideas, and were even ready to take the kids back home, but he was confident in his position and reassured them that he had experience in the past with these issues and that they should trust him.

“The next morning after breakfast, I assembled the teenagers in the lobby,” Rabbi Stolper told Mishpacha in the 2013 interview. “I stood on a chair and said, ‘I would like to give you an idea of our program for today. This morning at ten o’clock, the boys will go swimming and the girls will play volleyball. After lunch, the girls will swim and the boys will play baseball. Any questions?’ To the utter amazement of all the adults present, there was total, eerie, holy silence. Not a sound, not a murmur. No one said anything. I hesitated for a moment, and then, as though nothing important had happened, casually said, ‘Great, let’s proceed to our first activity.’ It was in those crucial moments that NCSY as we know it today was born. It was the teenagers who had won the day. They had no problem with the new rules.”

Rabbi Stolper had perceived a deep truth, on which all of the ensuing success of NCSY would be based — that these youngsters could be trusted to think straight and to choose for themselves an honest, coherent, and inspired path of Orthodoxy — with all of its rules — over the inconsistent, compromised, and bland Judaism that was the norm even in the Orthodox synagogues of the time, many of which had long before decided to forgo the mechitzah in order not to disenfranchise the youth. Unlike the rabbis, youth directors and parents who thought all their kids wanted was social dancing, ice skating, and hay rides, Rabbi Stolper believed in the maturity and spiritual aspirations of his young charges, and they richly rewarded his trust. (Still, he was a young 20-something rabbi at the time, and didn’t want to be an upstart. So as not to go head-to-head with the established institutions, he stayed away from arguing halachah and instead simply attributed his stipulations to OU policy.)

Rabbi Stolper had another innovation: He appointed teens as officers of chapters and regions, which empowered them to make NCSY their own organization, and they rose to his trust in them, as he empowered them to do what it took to make the organization a success.

Rabbi Stolper would continue to infuse NCSY with the passion of Torah observance by inviting gedolim such as Rav Mordechai Gifter, Rav Simcha Wasserman, Rav Nachman Bulman, Rav Yaakov Weinberg, Rav Henoch Leibowitz, and Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik to participate and speak at the national and regional events. One NCSYer recalls Rav Soloveitchik speaking to a group of kids with ponytails about the machlokes between the Rambam and Ramban regarding the obligation of tefillah. A revolution was taking place, all under the guidelines of Torah and halachah, and soon, more and more youth wanted to join NCSY and get a taste of what it meant to be a Yid. The success of NCSY brought along changes in the synagogues as well. Rabbi Stolper insisted that when an NCSY event came to town, the hosting shul would be required to have (or install) a mechitzah. Imagine their shock when, suddenly, their shul would fill up with hundreds of enthusiastic teenagers keeping Shabbos, most of whom were not Orthodox.

In 1963, Rabbi Stolper described the accomplishments of NCSY in that historic article in Jewish Life, attributing NCSY’s growth to its commitment to halachah and Torah. A few weeks later, he received an angry letter from a prominent Modern Orthodox rabbi accusing him of “Kotlerism,” referencing Lakewoood’s Rav Aharon Kotler and implying that Rabbi Stolper was being too halachically strict with the kids by not letting them enjoy social dancing and other halachically-compromised events. Rabbi Stolper, for his part, was immensely proud of the letter and would frequently show it. He knew that adherence to halachah was the only path, and no one could convince him otherwise.

Rabbi Stolper was once driving Rav Hutner to yeshivah, when Rav Hutner turned to him and exclaimed, “Mashiach kumpt nisht, mir darfen ehr brengen mit chutzpah [Mashiach won’t just come, we must bring him, with chutzpah]!” Rabbi Stolper lived his life with chutzpah, constantly battling for the upholding of halachah and building up NCSY against the odds. One day during an especially challenging period, Rav Hutner called Rabbi Stolper into his office and encouraged him in his booming voice, “Ich bin mekaneh dein chelek in Olam Haba [I am jealous of your portion in Olam Haba]. You are a lifeguard in a sea of drowning people.”

For Rabbi Stolper, a group of kids looking for a spiritual injection was as important as a meeting with an Israeli prime minister or a US president. Because it was never about him

No Taking Credit

Rabbi Stolper always considered that one of his greatest accomplishments was recruiting Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan a”h to write for NCSY. Rabbi Stolper first encountered this extraordinary individual when he spotted his article, “Immortality in the Soul” in Intercom, the journal of the Association of Orthodox Jewish Scientists. Rabbi Stolper was overwhelmed by Rabbi Kaplan’s ability to explain an almost untouched, difficult topic, which was usually reserved for advanced scholars, with such simplicity that it could be understood by any reader. “I had no idea who he was. I had never heard of him,” Rabbi Stolper later recalled. “But the article hit me like lightning. I remember pacing the floor, saying, ‘I must call this man.’”

It was clear to Rabbi Stolper that the special talent of this relatively unknown young frum physicist could fill a significant void in English Judaica, and he invited Rabbi Kaplan to write on the concept of Tefillin for NCSY. Rabbi Kaplan completed the 96-page manuscript of “G-D, Man and Tefillin” — with footnoted sources from the Talmud, Midrash and Zohar — in less than two weeks. The comprehensive, inspiring yet simple book set a pattern which was to characterize all of Rabbi Kaplan's successive works, and catapulted him to the status of the renowned author we remember today.

Despite all his accomplishments as a kiruv revolutionary, Rabbi Stolper never credited himself with anything, always stating that he was just at the right place at the right time. He saw himself as a messenger of Hashem, which gave him the fortitude to keep moving forward against the odds. During the shivah, countless people came in and exclaimed, “If not for Rabbi Stolper and NCSY, I wouldn’t be a frum Yid with religious children and grandchildren.”

Rabbi Akiva Stolper remembers once seeing his father receive a sefer from Eretz Yisrael and clutching it against his heart with his eyes closed. Reb Akiva asked, “Abba, what’s so special about this sefer?” And Rabbi Stolper replied, “The author of this sefer was in NCSY. I remember when I met him for the first time, he knew nothing!”

Throughout his years in NCSY, Rabbi Stolper would continue to consult Rav Hutner, who for 15 years lived across the street from him on Rockaway Parkway. Many years later, well after the age most people hang up their work clothes and retire, Rabbi Stolper embarked on the massive project of the first-ever English translation of the words of his revered rebbi. The seforim Pachad Yitzchok are classics in Jewish thought, but Rabbi Stolper felt that those who weren’t talmidim or hadn’t heard the maamarim directly from Rav Hunter had difficulty grasping the concepts.

Rabbi Stolper led NCSY until 1976, when he was appointed executive vice president of the Orthodox Union, NCSY’s parent organization, a role he’d serve for the next 18 years. This would open a whole new vista in his communal work – and he would continue to use his trademark chutzpah. In 1977, Rabbi Stolper and several other delegates met with President Jimmy Carter. In the Oval Office, Rabbi Stolper handed the president a Chumash with a handwritten note on the front page, quoting the first Rashi in Bereishis (that Hashem created the world and bestowed it upon Klal Yisrael). The message was clear: Eretz Yisrael belongs to the Jews, and Rabbi Stolper wasn’t afraid to share the truth. That was the propellor of Rabbi Stolper’s life: Don’t be afraid to stand up for what you believe in. If your goal is l’shem Shamayim, Hashem will help.

Rabbi Stolper was also involved in the plight of Russian Jewry, traveling to Moscow during the years before the iron curtain fell. After realizing how many Russian Jews didn’t know how to daven, Rabbi Stolper collaborated with ArtScroll to produce a siddur with Russian translation.

In his later years, he became involved in archaeology, believing that by proving ancient Jewish history really existed, Jews would be convinced of the authenticity of the Torah. Rabbi Stolper even funded books on archaeology written by other authors. For Rabbi Stolper the equation was simple: if it could bring one person back to Yiddishkeit, it was all worth it.

Yet despite his untiring efforts for the Klal, he was always there for his family and all those around him. His daughter, Rebbetzin Michal Cohen of Chicago, recalls how her father eschewed the lectures and instead taught by example. She remembers once watching him feed a lost kitten with an eye dropper at three a.m. A grandchild remembers how, at eighth-grade graduation, Rabbi Stolper approached his principal, saying he believed his grandson deserved an end-of-the-year award. The principal replied that, unfortunately, all the awards were already given out. “What about the Middos award?” asked Rabbi Stolper. “We don’t have one,” answered the principal. Rabbi Stolper put his hand in his pocket and pulled out a one-hundred dollar bill. “Now you do,” he said. That yeshivah now gives out a Middos award every year. When a rabbi who taught in NCSY was niftar, leaving behind nine children, Rabbi Stolper arranged a fund for the family, raising hundreds of thousands of dollars, and signed as a parent to pay the children’s tuition.

In their later years, the Stolpers moved to Lakewood where they lived for over a decade and where Rabbi Stolper helped build the Ateres Yeshaya shul; they then moved to Chicago in order to live near their daughter and son-in-law, Rabbi Zev and Rebbetzin Michal Cohen. There, too, Rabbi Stolper continued to inspire people with his energy. In Chicago, Rabbi Stolper had a visitor who came to speak to him about the history of NCSY. At the end of the interview, Rabbi Stolper commented, “Some people plant seeds and never see anything from them, but when I look around, I see a forest.” —

Readers who have memories or stories of Rabbi Stolper are invited to share, at rabbistolpermemories@gmail.com

The Approbation

By Rabbi Dr. Ivan Lerner

I'D first heard of NCSY from a public-school friend who said that there were “cool” rabbis and lots of fun to be had at the NCSY shabbatons. And so, in June of 1963, I was on a bus with 40 other teens from the Baltimore-Washington area, enroute to the Pine View Hotel in South Fallsburg, New York. It was there that I met Rabbi Stolper and his wife Elaine for the first time. It was a life-changing experience. I was finally introduced to a Jewish world that I could relate to – it was like nothing I’d ever experienced.

I would eventually become a chapter president, a regional president, and a National NCSY board member. In 1967 I married Arleeta, another NCSYer I’d actually first met at the Pine View, and in 1970, Rabbi Stolper recruited me to become the first director of NCSY’s Central East Region. The region’s borders stretched east to west, from western Pennsylvania to Indiana, and north to south from southern Ontario to northern Kentucky. Rabbi Stolper and I agreed that the regional office needed to be in Cleveland.

Just prior to my relocating, Rabbi Stolper mentioned that as soon as I arrived in Cleveland, I should set up a meeting with Telshe Rosh Yeshivah Rav Mordechai Gifter. He asked me to deliver Rav Gifter a personal letter from him, and also asked me to try to get a few of the Telshe kollel talmidim to help NCSY’s kiruv efforts in the Central East region.

At the time, I didn’t realize that the envelope also contained a haskamah (approbation) from Rav Yitzchok Hutner, who wrote about the work that NCSY was doing to save neshamos, and that his talmid muvhhak, Rabbi Stolper, was being moser nefesh in his holy (and successful) efforts of saving Jewish teenagers from assimilation.

Upon arrival in Cleveland, I immediately made an appointment to meet with Rav Gifter. At this point I need to interject that every rosh yeshivah I’d ever met spoke Yiddish (and very limited English) and came from the great yeshivos of prewar Europe. Some, like my high school rebbi, had arrived in America via Shanghai. Because my Yiddish was sub-par, I was somewhat apprehensive about having a one-on-one meeting with the Telshe rosh yeshivah, but I was on a mission, so I drove out to Wickliffe, Ohio, to meet Rav Gifter.

After waiting outside the Rosh Yeshivah’s study for a few minutes, I heard a small commotion coming from the hallway, and someone said “Rav Gifter just walked in.” A minute later, an older bochur asked if I had an appointment. I said I did and gave my name. All the while, the tension inside of me was building. The bochur said, “Please knock on Rav Gifter’s door and wait for a reply.” I did as I was instructed. The strong voice from inside said, “Come in.” I entered.

I explained why (I thought) I came and what I thought I was doing for NCSY. In a very nice way, Rav Gifter explained that while he respected the great work that NCSY was undertaking, it wasn’t appropriate for him to send Telshe bochurim to work directly with us. I then handed him Rabbi Stolper’s envelope. He opened it, read it, and paused — and reread Rav Hutner’s approbation. Stroking his beard and thinking hard, Rav Gifter said, “Maybe there are one or two talmidim I can send.”

Rabbi Dr. Ivan Lerner, a clinical and industrial psychologist, has served as an elementary and high school principal and community rav. Arleeta has been a day school principal, teacher, and counselor for many years.

He Never Backed Away

By Rebbetzin Michal Cohen

AT my father’s 80th birthday party, I told him that my trust in Hashem had its roots in the deep trust that I had for him. Although my father was a remarkably busy man, with a burning mission to spread the word of Hashem, to me that mission began at home with the three of us. On Friday night when it was time for Bircas Habanim, Abba would call out “bentsh babies” and we would come running. He would put his hands on our heads (one of us would have to settle for an arm) and when he gave us his brachah, I always felt Hashem’s presence. On Erev Yom Kippur, Abba would be dressed in his tallis and kittel and would call us in one by one to receive his brachah. As soon as he started, he would begin to cry, and by the time he was done, we would both be in tears — tears that continue to nourish me.

My father taught by example. I learned to care about all people from watching him calm a choking girl at a theme park when I was 12. I learned about love for Eretz Yisrael when he put up a map of the country after the Six Day War, with the newly captured land highlighted and the words “kulo shelanu” written on top.

Abba was a scholar and a leader, but at home he was the fix-it man, solver of all problems, artist, decorator, and maker of potato kugel and coleslaw. “Zaidy fix-it” was one of the many loving names the grandchildren had for him. Another was “Zaidy Eim,” the name he acquired when my parents became great-grandparents. My mother didn’t want to be called “Savta Rabba,” at she associated the moniker with very large people. So she chose the name “Savta Eim” instead, adding “mother” to “grandmother.” My father thought that was beautiful, and decided, in his characteristic unassuming nature, that if it worked for his wife, it would work for him too.

His great-grandchildren would raid his office — they called it “Staples” — and came away with pens and pads galore, which he would later recollect once they abandoned them.

My son Dovid Elisha shared with me how on one hand Zaidy was on his wavelength, yet at the same time was always expanding his horizons. He remembers the inscription on a set of machzorim he received for Chanukah as a young child. Zaidy inscribed a lofty message, then added, “You may not understand my words fully now, but I know one day you will.” This was typical of the way he interacted with people. He was very present but also always inspiring the future. He had incredible patience for everyone. My son Shmueli remembers Zaidy once taking him shopping as a teenager, to a few stores with hundreds of choices of suits but accepting, with both respect and bewilderment, that he could not find one that met with his approval.

My brother Rabbi Akiva Stolper related a beautiful story that sums up my father’s essence. He related that the Radziner Rebbe comments on the pasuk, “Vayichan sham Yisrael neged hahar — Bnei Yisrael camped [in singular] opposite the mountain,” as the ability for Klal Yisrael to turn their backs on the rest of the world and turn toward Hashem. Akiva remembers my father kissing the Kosel when he was about to depart Eretz Yisrael, walking backward the entire length of the plaza and crying. He asked Abba why he was so sad. Abba responded that it was so hard for him to return home and leave Eretz Yisrael. My intuitive brother, then just 12 years old, responded that it would be okay, as he was returning to America to build the Beis Hamikdash. Abba was always looking to intensify his kedushah and ours. He backed away from the Kosel, but that’s because he never backed away from anything and met all challenges with determination.

Abba, Zaidy, Zaidy Eim, we know you have thousands upon thousands of spiritual descendants, but we — your children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren — feel so blessed to have you as our own.

Rebbetzin Michal (Stolper) Cohen, a clinical social worker in private practice and director of kallah education for Daughters of Israel, is the rebbetzin of Congregation Adas Yeshurun in Chicago, where her husband Rabbi Zev Cohen has served as rav for 35 years.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 917)

Oops! We could not locate your form.