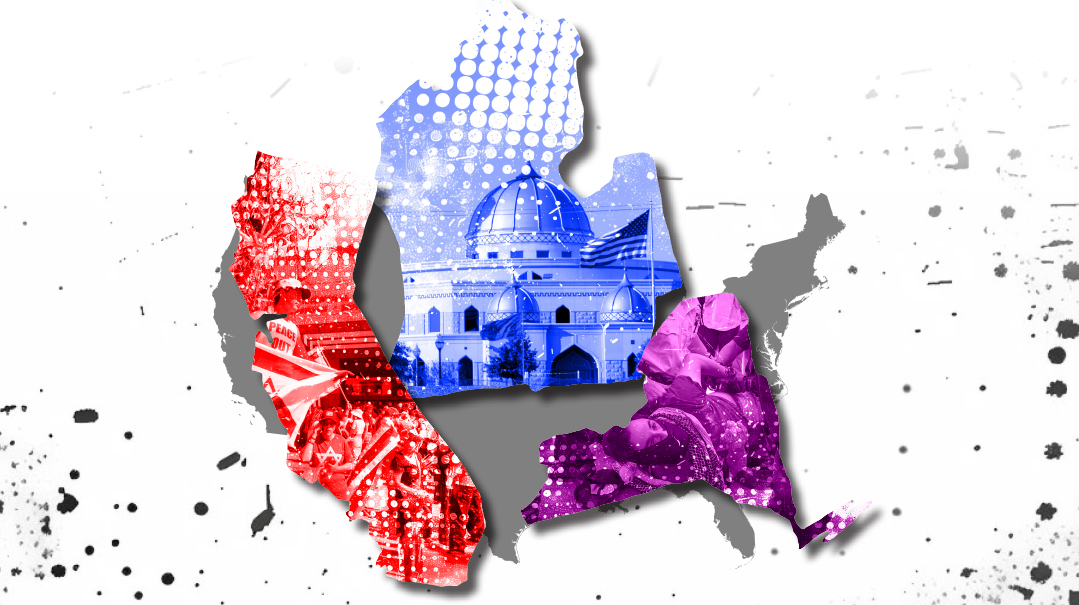

Hate across America: 3 accounts

| July 2, 2024Current events have uncovered a deep rot within our cities and suburbs—an ancient hate rooted too deeply to ever eradicate

The Protest on Pico

As told to Rivki Silver by Rachel M.

ON

Shabbos, the rav warned us there would be a protest. His shul, Adas Israel, would be hosting a real estate fair featuring a group of real estate agents and developers who’d flown in from Israel to promote their new properties. The protest would be held across from the building on Pico Boulevard, the rav informed us, and he encouraged us not to engage with them. In this new normal that we’re all adjusting to, this advice came as no surprise.

Early Sunday morning, our block chat pinged:

Everyone take your car out of the driveway and put it on the street. Block as many parking spots as possible so protestors can’t use them.

One of my neighbors knocked on my door to let me know that I should move my car. Other than that, the day started off like any other summer Sunday.

Around noon, I brought my son to a friend’s house and drove past the shul on my way home. There was nothing doing, not a single protestor in sight. Another one of those situations where there was a lot of hype but ultimately a non-event, I thought.

Shortly before one, my husband and I and our seven-year-old son decided to walk over and check out the fair. Two of my older sons were already there.

As soon as we stepped outside (I live very close to the shul — only about 150 feet away), I could tell that it was not the non-event I had thought it would be. We could hear from the alley that there was trouble nearby, and as we came onto Pico Boulevard, all I could see was chaos. It was clear that the protestors were not being confined to the other side of the street as we’d been told; they were everywhere.

They had blocked off the entrance to the shul and were in the middle of the street as well. They were mostly all in black, some with green or red, most with kaffiyehs and masks on, holding signs and waving Palestinian flags. We saw a child holding a sign that said, “Intifada Now.” Car alarms were going off. A woman on a megaphone was leading a chant, screaming, “From the River to the Sea,” while a frum man was yelling, “All the hostages will be free!” into a microphone to counteract the pro-Palestinian chants. Jews were walking around with Israeli flags draped around their shoulders. I heard intermittent screams and a constant low thrum of yelling, fighting, and women screaming, “Stop! Stop it!” People all over were filming the melee on their phones.

The Jews and the protestors were completely mixed together. All around it looked like little fights. I saw two men shoving each other back and forth when suddenly it escalated into a much larger fight with half a dozen people punching and kicking each other. It was surreal to watch rebbeim in suits and black hats breaking up the fight, pulling people apart, picking people up off of the ground, asking them, “Are you okay?”

I was surprised at the number of older protestors I saw, even though it was hard to see anyone because their faces were so thoroughly covered. But I could tell that there was a shocking number of protestors in their fifties and sixties. Are they the true believers in all that disgusting anti-Israel propaganda?

I stood on the periphery with my son while my husband, who by nature is a very calm man, went over to talk to some of the protestors. There were maybe a dozen LAPD police officers just standing around, but it was the volunteers from Magen-Am, our Jewish security agency, who were keeping the protestors from storming the shul. I saw a volunteer in a yellow vest walk over to a group of riled-up teenagers and tell them, “It’s not worth it, calm down, step away.”

My mind was not processing the situation. I had just been here 45 minutes earlier and it had been calm. How had this happened? I watched in shock and horror for a couple of minutes and then I saw an orange spray in the air and felt something stinging in my eye. My little son started screaming that he felt something in his throat.

I was scared, but I was more worried about my son. He was really scared and I felt terrible. I thought we had been standing in a relatively safe spot, a good 20 to 30 feet away from any fighting; the wind must have carried the spray to us. I went straight into focused-Mommy mode to get us to safety. I left with my son, leaving my husband and older sons at the protest.

As we were trying to get out, I just kept telling my son, who was crying by this point, “You got a little spice in your mouth, it’s just some spice, we’re going to go home and rinse it out and I’ll give you a Popsicle.”

But even once we were safely inside my house with the door locked, my heart was still pounding. We could hear the chaotic sounds of the protest as well as the sound of multiple helicopters circling overhead. I checked a neighborhood WhatsApp group and saw that someone had posted that they were thinking of heading over to the fair. “Don’t go,” I responded immediately.

When my husband came back, I wanted to go and look for one of my older sons, who hadn’t been responding to his texts. I just needed to see that he was all right. It was around two thirty at this point.

I hopped on a bike but didn’t get very far because the end of my block was filled with 50 to 100 people from the protest. On my street, my completely residential street, I watched, aghast, as I saw women in hijabs and face masks standing around with men whose heads were completely wrapped in red and white kaffiyehs. I heard Jews screaming at the protestors, “Get out of our neighborhood! Just go back home!” There was a random guy with a bullhorn talking about the Noahide laws. It was a balagan. There were no police anywhere in sight.

Completely frazzled, I circled around to Pico Boulevard, and I saw all the police standing there. Apparently, they’d declared the protest an unlawful assembly and shut down the street, but then the protestors just moved to residential streets. Our streets.

Since October 7, we’ve unfortunately gotten used to a certain level of craziness with the anti-Israel protestors. Around Pesach time, there were those protests at UCLA, but the threat was always somewhere else, somewhere you had to make an effort to get to. Now things had escalated. They had brought the threat to our doorsteps.

After nearly a year of heightened anti-Semitism, the Jewish community is under so much stress. People are like loose cannons ready to explode. All the men, the teenagers, the dads, they’re sick of it, they’re frustrated, they’re mad, and many of them didn’t have the patience to just stand by and not engage with these protestors who were doing everything they could to incite us. Two of my older sons were at the protest for a few hours, and one told me how there were a number of Jewish moms who were preventing escalation by verbally and even physically holding boys and men back from fighting with the anti-Israel protestors.

Not long after I left my house, my son finally texted my husband back. “I’m fine, sorry I didn’t text earlier.” My relief was palpable. I went back home, but it was still a stressful, dramatic scene. We saw protestors parking on our streets. I stuck my head out of my house and saw a protestor all in black skateboarding down the sidewalk. All the block chats were full of women reporting where they were seeing protestors. I could still hear helicopters over our neighborhood. It was scary in the moment, but the fear I felt was more for what the future might bring.

Finally, around six thirty, when things had calmed down enough that I felt safe to leave my home, I decided that I did, in fact, want to go to the fair. While I was there, chatting with one of the Israeli women, she said something about today being a “memorable day, for sure.”

“I’ll never forget this day,” I replied somberly.

“What do you mean?” she responded with surprise. “This is worse than normal?”

I was so confused by her question.

“Everywhere we go, there are protests,” she continued, with a shrug.

Out of Control?

Erin Stiebel

W

ith an hour to kill between camp carpool pickups, I bravely decided to take my two youngest with me to T.J. Maxx to make a few returns. Usually I bump into one or two other frum people at this T.J. Maxx, but today, it seemed like it was just us. My sweet little children were particularly spirited, probably a result of lack of sleep due to the sun setting offensively late this time of year. With my three-year-old in the cart and my five-year-old trailing behind me, I turned into the next aisle which, unfortunately for me, was the toy aisle. And that’s when it began.

“Can I have this? Wait. No. THIS!”

I was shooting nos in every direction, empathetic but non-budging. My five-year-old’s volume began to rise. One notch, two notches, then reaching that volume that invites everyone in the vicinity to gawk at the scene. Normally, I would step into supermom mode and handle the meltdown, but in today’s climate, all I could see were his tzitzis and yarmulke and the fact that we were visibly Jewish.

“Stop. Get up,” I muttered. “We can’t scream, sweetie. We need to make a kiddush Hashem. A KIDDUSH HASHEM. Did you hear Mommy? Look at you in your tzitzis and yarmulke! This isn’t making a kiddush Hashem!” The lecture continued as we quickly finished our returns, smiled abundantly at anyone who looked at us, and then hurried out of the store.

My kids know that Mommy’s Kiddush Hashem Speech has taken the forefront of all our public outings lately. Of course it’s something I grew up hearing, but it’s now so much more necessary. Intellectually, I know that those who hate us will hate us whether my child is having a tantrum or not, but it feels like all I’m in control of here — and if I’m being real, it’s so hard that so much is out of my control these days.

As residents of the Detroit Jewish community, we live knowing that just 15 minutes away from our beautiful sheltered community lies Dearborn, the largest Arab and Muslim city in America. That makes my must-make-a-kiddush–Hashem-everywhere-I-go-o-meter fly off the charts.

My oldest recently asked if we could go to one of our favorite climbing places, located in the suburbs of Dearborn. I casually dismissed the suggestion and offered another option. “Why can’t we go there?” my son asked. “Is it because you think the people there don’t like Jews?” I froze. His question caught me off guard and I didn’t know how to respond.

Was he asking this because an office building around the corner from our house was recently vandalized and graffitied with “Free Palestine” and anti-Jewish slurs? Was it because some of his friends were cursed at by kids at an amusement park? Did it have to do with the doctor mentioning that he’s been worrying about us recently? Or did he notice all the hijabs last time we were there and make an assumption?

I looked at him, with pain in my heart and prayer on my lips, asking Hashem for the right words. “The truth is,” I explained, “I don’t know how they feel about us. And since I don’t know, I’d rather not go there.” With a child’s innocence, he responded, “Last time I was there I played with a boy named Ahmed. He was nice. Maybe the other people will be nice, too.”

My sweet, loving little boy. Ingrained deep in the souls of our nation is an unadulterated love, an instinctual kindness, and the ability to see people for their inherent goodness. We strive to be oheiv shalom v’rodef shalom, and we live by the principles of morality and ethics. And like my son, we assume that the rest of the world lives by those same values. So how do I explain to him that the world is filled with people who hate us for no reason and see us through tainted eyes, twisting realities to fit their narrative?

Instead, I just hug him. And we go to the less-exciting climbing place.

I know that everything is out of my control. I know that my fears and worries don’t get me anywhere. I know that the forwarded texts of anti-Semitic incidents around the US aren’t helping, either. My brain knows this. My mind seems to have not gotten the message.

A conversation with a student shakes me into reality. Jenny, a traditional and respectful young woman who has been coming to our kiruv programs for a few years, approaches me after class with a serious question. “How can you stand up there and tell us to trust in Hashem and have faith while everyone in the whole world seems to hate us? Even our own communities feel unsafe!”

Jenny’s right. It seems audacious to talk about all the hate and the fear, and then to wrap it all up in a little package sealed with emunah.

As I respond to her, I feel myself looking inward and responding to myself as well.

“You want to know how I can talk about emunah throughout all of this? How I can trust in Hashem as I watch the Jewish people suffering, living in fear, and burdened by uncertainty? This is the way of the Jew,” I tell her. “Ani ma’amin. It’s because I trust in Hashem. I know, with complete clarity and faith, that Hashem is in control of all of this. He’s in control of the good times and the miracles, and He’s in control of the bad times that I will never understand. He is the master puppeteer, pulling all of the strings, and every single creation in This World is in His show.

“And in those moments where I have no clarity as to why such horrific things are happening to us,” I explain, “I accept that this is our galus — an exile of confusion — and then choose faith all over again. I am actively making the choice to trust that Hashem has a plan and knows better than me, because the alternative leaves me trying to navigate this confusion on my own. Gam ki eileich b’gei tzalmaves, lo ira ra, ki Atah imadi. No matter what we are facing and no matter how daunting it is, we have nothing to fear because Hashem is with us.”

I conclude by sharing an interaction I witnessed between two of my boys a few years ago. “I had just returned from the grocery store and had a trunk full of groceries. My four-year-old wanted to carry in a bag that was filled with heavy cans and jars. I told him it was too heavy for him, but he’s a very confident — and stubborn! — little boy, and he was determined to lift the bag on his own. After a few tries, he realized that the bag was just too heavy. My seven-year-old, who’d watched the situation unfold, went over to him. ‘I see you really want to help Mommy carry in that bag. How about you take one side and I take the other, and we can carry it in together?’ And so they did.

“This,” I tell her, “is the gift of emunah. When things get hard and are too heavy for us to carry alone, Hashem is always there, ready to share the burden and carry the other side of the bag. When the world feels daunting and the news is too painful or scary to bear, I turn to Hashem to hold me, because I know with confidence that He is in control of it all and needs me to trust Him.”

Jenny is quiet.

“I envy your faith,” she whispers.

And as I stand in front of her with deep, rock-solid, genuine confidence, I envy my faith, too — in the moment, it can be hard to tap into it. But I am comforted by this critical reminder that underneath all of my worries and fears, my bitachon is as strong as ever.

An Open Letter

Rachel Diamond

Dear Professor _____,

I received my doctorate last week from the New York university of which you’re a faculty member. The commencement event was traumatizing for me as I am sure it was for many Jewish students. Several days later, I am still distraught. As you were the senior faculty member chosen to represent the college and deliver the keynote address — and a fellow Jew — I’m hoping to achieve some degree of closure by expressing to you the impact that your speech had on me.

I celebrated the milestone of graduation alone after all those years of working toward my degree. I told my family not to attend the graduation ceremony as they are visibly Jewish, and I didn’t want them to experience a potentially anti-Semitic scene. When I saw the Palestinian flag hanging from the balcony in the auditorium, I knew I’d made the right decision.

Because any illusions of safety Jews may have entertained previously have been gone since October 7. And if I ever begin to feel safe again, all I need to do is remember my graduation to shatter that feeling.

It’s an evening I won’t be able to forget.

I sat through your speech and cried. Did you know that there was a girl among the graduates crying through your speech? Every word, and every cheer in response to your words, was a knife in my heart. I sat there with half my mind back on that black, black day in October, the other half worrying about what will be with us, the Jewish people in America, in the future.

I can’t describe how vulnerable I felt sitting in an audience of my peers as they cheered at your call for a ceasefire in Gaza, cheered when faculty members unfurled a poster behind you declaring the students’ “Five Demands for Palestine,” cheered when you praised the “encampments marking solidarity with publics that are under assault,” cheered when you called to drop “the outrageous felony charges” against students who set up the encampments on campus, cheered when you called for “being able to express ideas without adjudication by Congress,” cheered for the people who slaughtered, or celebrated the slaughter, of my people.

The cheers were so loud.

It felt like the room was closing in on me.

Grainy footage of Hitler rallies played in my mind.

Then I shook myself back into the present and saw you on the stage, Professor ____.

You incited them.

There was a woman who interrupted the president’s opening speech with anti-Israel shouts and calls to “remember the universities in Gaza,” but nobody joined in her protests. In fact, her interruptions were promptly silenced by someone in the crowd, a move applauded by several audience members.

But when the hatred was sanctioned by you, a member of the faculty itself, a Jewish member of faculty, the room exploded. You, who I’m sure pride yourself on rigorous research and evidence-based knowledge, had no compunction in delivering a speech filled with blood libels. (“Unspeakable violence that is decimating communities, killing civilians, and murdering children”? Can I assume you’re speaking of October 7?)

The second you began your ceasefire rant, I froze, and instantly, two (non-Jewish) classmates on either side of me grabbed my hands and held them for the remainder of your speech. These kind girls instinctively knew that the Jewish student next to them was suffering. They knew that the oft-repeated claim that “anti-Zionism is not anti-Semitism” is a myth.

What started off as a graduation ceremony morphed into what felt like a pro-Palestinian rally. Every student who walked up in a kaffiyeh, every anti-Israel slogan that was shouted from the stage, every “Free Palestine” sign that was carried made me catch my breath and want to cry out for the terror victims whose memory was being trampled.

Your call to free the hostages, said in the same breath as your call for a ceasefire, made me sick to my stomach. How could you imply that there is moral equivalency between the hostages and the murderous population who took them hostage? Did it not strike you as incongruous to call for the release of the hostages in the very same speech in which you called for the protection of those who captured them?

The audience weakly applauded your call for the hostages’ release — as if they care two straws about them — weakly applauded your call for an end to the genocide in Sudan, weakly applauded your call for an end to racism, and went wild when you called for a ceasefire in Gaza. If only they expended a fraction of their effort in calling for Hamas to release the hostages as they do in calling to reward Hamas, perhaps there would be far fewer brokenhearted Israeli families today.

Professor ____, do you feel you’ve been punched in the gut when you find out that a hostage has been murdered?

I do.

I know every one of those hostages by name. I’ve prayed for each and every one of them every night for the past eight months. Have you? Has anyone else in the audience?

Of course not.

Why should they?

The hostages are Jewish.

It’s been a nightmare of a year for me. And the commencement was a fitting end to it. I lost 1,200 siblings in one day. And I know they died in agony. There is no comfort for that. The special people of ZAKA, who were the first to find the victims, said that they could tell they died weeping.

The world will move on, but we, the Jewish people, never can. Do you know what they did to those people? Do you know how they killed them? Do you know what they did to them before they killed them? Do you know what was left of them after they were done with them?

And if you do know, the question you need to ask yourself is this: Why don’t I care? What makes me into the monster who can call to let their murderers walk free?

The pain we feel didn’t start on October 7. Do the names Nachshon Wachsman or Naava Applebaum mean anything to you? What about the Paley brothers, the Yaniv brothers, or the Dee mother and sisters? Do you know of Eyal Yifrach, Gil-Ad Shaer, and Naftali Fraenkel? The Fogel family? And if you don’t, I want to scream: Why not?!

What you may know deep down, Professor ____, is that the next time they come after us, they won’t distinguish between you and the rest of us Jews. So many self-hating German Jews, who were said to be more German than the Germans, were shot in the same pits and murdered in the same gas chambers as the Jews who were true to themselves.

Betraying your nation won’t save you.

Have you ever taken a good, hard look at yourself, Professor ____? Will you do it now and ask yourself, “What is it that drives me to incite a mob against my own people?”

A grieving, distraught, and frightened Jewish student

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 900)

Oops! We could not locate your form.