Halachic Arbiter In A Medical Maze

| March 2, 2011Among the many burdens shouldered by Rav Moshe Feinstein was his role as halachic arbiter in the rapidly-developing field of medicine. An astounding number of innovations spawned an equal number of questions. No matter what that subject – be it hearing aids, cancer drugs, reproductive medicine, or end-of-life issues -- Rav Moshe ruled with clarity and authority. Three physicians who merited personal access to Rav Moshe recall the giant who served as the era’s halachic beacon

A

fter World War II, the United States became an international leader in scientific and medical advances. The pace of medical progress was dizzying and, for many people, disorienting. Antibiotics, advanced surgical techniques, CAT scans, organ transplantation, drugs for cancer, and ventilators were just some of the innovations that rapidly became routine. Medical care was now being delivered in large impersonal hospitals by teams of specialists who had not previously met the patient or his family and had no knowledge, and sometimes no concern, for patients’ values and beliefs.

These developments spurred many difficult and novel halachic quandaries. Can a patient who is dying or has no chance of cure be taken off the respirator? Who can make decisions for a person whose mind is clouded or ability to make decision is impaired? Should doctors perform a risky surgery that can cure a terminal patient who will surely live for some time without the surgery that could kill him?

Observant Jews needed answers.

At the same time, increasing numbers of young Orthodox people were entering the field of medicine. They faced a system that was not sympathetic to their religious observance and that educated through total immersion in medical lore and impatient care. Decades earlier, doctors-in-training were required to live on the hospital grounds for several years, thereby gaining the name “interns” or “residents.” This ethos persisted into the postwar period. Interns and residents, though they no longer lived on hospital grounds, were working thirty-six hour shifts, sleeping very little, and functioning under the continuous scrutiny of their superiors. Religious Jews hoping to become doctors were beset by halachic questions. May a religious physician perform or participate in an autopsy? Can he or she dissect a cadaver in the anatomy class? Is it possible to attend conferences on Shabbos or even present medical research in them, and if so, how?

Because the consequences were so great — involving life and death — these medical students sought a rav who could authoritatively pasken (decide) new and complex sh’eilos. It was only natural that they turned to America’s premier posek, Rav Moshe Feinstein, or Reb Moshe, as he was affectionately known. In fact, for many years Reb Moshe served as the posek (decider) for the Association of Orthodox Jewish Scientists, a prominent and influential organization at that time. AOJS, as it was known, included the Rephael Society, a society of religious doctors.

Whereas in Eretz Yisrael, a number of poskim dealt with medical halachah (including but not limited to Rav Eliezer Waldenberg, Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach, Rav Yitzchok Yaakov Weiss originally of Manchester, Rav Shmuel HaLevi Wosner of Bnei Brak, and Rabbi Ovadia Hadaya of Jerusalem), in America Reb Moshe was unique in his willingness to take responsibility for medical halachic issues. The entire burden of research and application in this complicated area dealing with its human aspects fell upon his shoulders.

A Customized Curriculum

D

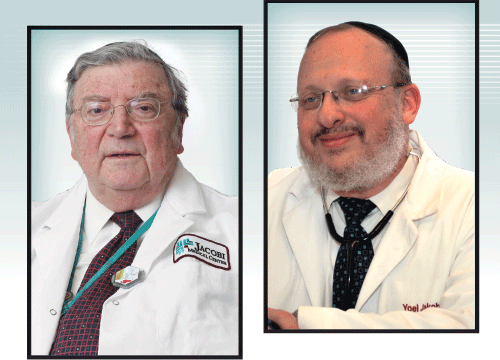

r. Melvin Zelefsky, currently the chair of radiology at Jacobi Medical Center and professor of radiology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, still remembers being introduced to Reb Moshe decades ago. In 1956, after pursuing rabbinic studies and a degree at Yeshiva College, Zelefsky enrolled in the newly opened Albert Einstein College of Medicine. At that critical juncture, he understood that he needed guidance and supervision to continue learning despite the pressures of medical training. Reb Moshe agreed to mentor the aspiring physician and guide him through the halachic issues sure to arise during his years of medical school. Not only that, the posek hador custom-tailored a Torah curriculum for young Melvin.

In a recent interview, Dr. Zelefsky described the details of their arrangement:

“I prepared topics with my chavrusa, Dr. Fred Rosner, who later became the chair of medicine at Queens Medical Center and professor of medicine at Mount Sinai as well as a prolific writer on medical halachah topics and translator of Rambam’s works. Once every week or two I would spend forty-five minutes to an hour shmuessing (talking) with Rav Moshe in learning. Rav Moshe recommended specific masechtos and topics for us to learn and prepare, and then we spoke about them. This, more than anything else, ensured that we prepare and work hard to stay in learning.

“Rav Moshe gladly gave his time. He was cordial and patient and available.”

Professor Fred Rosner writes: “I was privileged to know Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, of blessed memory, personally for many years … He was extremely gracious to me when I called him on the phone and interrupted his shiur to ask him about an autopsy consent. He personally offered me halachic guidance in many areas on many occasions…

“I vividly remember my first Sabbath in the hospital as an intern. I was on the seventh floor on a medical ward and heard my name paged on the loudspeaker. Out of ignorance, I did not pick up the closest phone to answer my page but ran down eight flights of stairs … across the street, where the telephone operators were located. To my exasperation, I learned that I was needed on the sixth floor of the first building that I came from…. This kind of activity continued throughout the Sabbath. On Saturday night I was totally exhausted and called Rabbi Feinstein, who empathically told me that I had done the wrong thing. I should have picked up the nearest telephone and answered my page because it might have been an emergency. ‘But ninety-nine calls out of a hundred are not an emergency,’ I protested.

“‘Even if only one out of a hundred calls is a real emergency,’ replied Rabbi Feinstein, ‘you must answer all hundred because you do not know which will be an emergency.

“‘Furthermore,’ continued Reb Moshe, ‘if running up the stairs takes more time than the elevator or leaves you panting and may thus interfere with your ability to properly evaluate the patient’s problem, you have not observed the Sabbath at all but transgressed the commandment of healing on the Sabbath’” (F. Rosner, Pioneers in Jewish Medical Ethics. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1997).

Dr. Zelefsky consulted with Reb Moshe regarding the preferred method of recording notes on Shabbos, for those occasions when he was unable to trade assignments and had to be on-call on Shabbos. Reb Moshe advised him to use a wire-recorder to dictate notes, which would later be transcribed and placed into charts. Wire-recorders, which utilized new technology, were expensive, and the young trainee could not afford the purchase, so he leased one. At other times, on Reb Moshe’s advice, he hired a nurse or an assistant to write the notes for him.

Privileged Access

R

av Moshe didn’t only teach his physician students what to do on Shabbos or how to behave in specific clinical situations. He also shared with them perspectives and observations that helped them understand how Torah viewed the practice of medicine and how they, as religious Jews, should advise others. Dr. Yoel Jakobovits, a prominent Baltimore physician and the son of Lord Immanuel Jakobovits, ztz”l, the late chief rabbi of the British Commonwealth and the author of the first English language book on Jewish medical ethics (in fact, he coined the term), first met Reb Moshe as an eleven-year-old, when his father visited Reb Moshe in his summer residence at the Zucker’s Hotel in Glenwild, NY. To this day he remembers the caring and concern that Rav Moshe showed for the young boy in dragging over a heavy wooden chair so that that the eleven-year-old would have a place to sit alongside his elders.

Many years later, Dr. Yoel Jakobovits had an opportunity to spend some time with the venerated posek. He relates: “Though it’s been thirty-five years since this incident, I still remember it; it had a great influence on me. At one point, Reb Moshe had experienced an arrhythmia [irregular heartbeat]. The family took him to Dr. Hurst, the world-famous expert on arrhythmias and the author of the authoritative textbook on that subject at that time. Dr. Hurst inserted a pacemaker. “Unfortunately, a few weeks later the arrhythmias returned. Reb Moshe went to the local emergency room, where a junior on-call doctor diagnosed a pacemaker malfunction, removed the defective model, and replaced it. Reb Moshe told me on that occasion, ‘Here I am with a pacemaker inserted after all by a trainee and not, as we planned, by the medical luminary (‘gadol hador’ is how he put it). This happened to me to teach that it is important for a Jew to remember that he must seek competent medical care, but ultimately, the outcome is in Hashem’s Hands and not in ours.’

“In my many years in the medical field, I have experienced this principle numerous times. The lesson that Reb Moshe taught remains with me, and I think about it often.”

Dr. Jakobovits also remembers a rare private meeting that he merited with the gadol hador. When Reb Moshe was elderly and unwell, the Feinstein family asked Dr. Jakobovits to attend to him during his stay in the Yeshiva of Staten Island during Rosh HaShanah. Dr. Jakobovits could not come, so he arranged for his colleague Dr. Neal Ringel to do so. Several weeks later, the rebbetzin phoned Dr. Jakobovits and invited him and Dr. Ringel to visit Reb Moshe so that the elderly rav could in some way reciprocate their kindness. The two physicians were served cookies and juice, and spent two hours in the Rav’s company. Before their meeting, anticipating their rare access to the premier posek, they prepared a list of ten medical halachic questions to discuss.“One thing that struck me,” says Dr. Jakobovits, “and really, the thing that anyone who studies Reb Moshe’s teshuvos immediately realizes, is the tremendous ‘hekef,’ his all-encompassing view of the sh’eilah. There was not an area of halachah that is germane to the topic that he did not touch. He was also a highly original thinker, deriving insights directly from Gemara and Rishonim. He would draw practical applications from the comments of Tosafos, for example.”Reb Moshe dealt with many issues that had never before been covered in halachic literature. His approach set the parameters for future discussions of these questions. At the same time that he was original, Rav Moshe was not dogmatic, and he did not insist that his approach was the only correct one. In the introduction to his first volume of responsa (Igros Moshe, Orach Chayim I), he wrote that his responsa represent suggestions and general guidelines and that each rav should use his own judgment and discretion in applying them to the facts of his particular case. Reb Moshe ascribed great importance to investing intense effort into understanding the specifics of each particular case and expected others to do the same. Moreover, he felt that each rav bears the responsibility of analyzing the primary sources on his own rather than blindly accepting Rav Moshe's reading of them.

Broad Shoulders

T

here is a Yiddish expression that is sometimes applied to poskim who are willing to take responsibility for decisions that set a precedent on weighty topics: “breite pleitses,” or broad shoulders. Rav Moshe had “broad shoulders” indeed. On issue after new issue he produced clear decisions that continue to serve as principles in the field of medical halachah. Dr. Zelefsky comments: “Sure, you could ask others these questions! But typically they would hem and haw and say something like, ‘Well, if the situation is this, then may be you can do that, and if it is such, that perhaps you should do something different.’ Rav Moshe was clear and to the point and you always got an authoritative answer from him.”

During Reb Moshe’s lifetime, medical advances gave rise to many new sh’eilos. Some were about how to apply known halachic principles to new situations, for example, whether a hearing-disabled person can go out with a hearing aid on Shabbos (Rav Moshe answered yes, see Igros Moshe, Orach Chaim 4:85), or if a patient can use alcohol-containing rubs on Pesach (again, he ruled leniently; ibid. 3:62). Another example that poskim previously discussed is whether temporary fillings and dental prosthesis are a barrier to ritual immersion (Yoreh Deiah 1:97). Others questions involved new technology or new situations. For example, RavMoshe wrote a number of teshuvos about organ transplantation (Yoreh Deiah 2:150, 174; 3:140, 141; Choshen Mishpat 2:72), a completely new issue at that time.

Dr. Zelefsky, an accomplished talmid chacham himself, was struck by Rav Moshe’s clarity and decisiveness in responding to questions that others feared to touch. “He dissected the issues masterfully,” Zelefsky explains. “Take for example the question of using an alcohol sponge prior to drawing blood on Shabbos. He covered every issue for us: is squeezing prohibited because it whitens or because you need the final product, is it a rabbinic or Biblical prohibition — every possible angle was discussed and considered.”

There were times when Reb Moshe’s decisions made the papers and were even cited in medical textbooks.

In October 1977 an unusual question was posed to Reb Moshe, a question that became precedent-setting not only for Jews but for ethicists world-wide. A religious Jewish family welcomed two infants, each one a precious human being, who were born joined at the chest and sharing one heart. Baby Girl B had an essentially normal, four-chambered heart that was joined at the main pumping chamber, the left ventricle, to a stunted, two-chamber heart of Baby Girl A. The connection was only one tenth of an inch thick — too thin to be surgically divided. The babies were transferred to the Philadelphia Children’s Hospital where doctors realized that if nothing would be done, eventually the heart would be overworked and neither child would receive enough oxygen to survive. On the other hand, if the two were separated, one child — Baby Girl A — had no chance of leaving the surgical suite alive.

The issue came to the hospital’s pediatric surgeon, a man of strong religious belief and a physician who would later become famous as the surgeon general of the United States under President Reagan, C. Everett Koop. Then as later, he was an outspoken defender of the sanctity of life. He knew that there were many unknowns in this kind of ground-breaking surgery, among them its ethical and religious sanction. Can one sacrifice one life to save another? On the other hand, can one not perform surgery knowing that this course of action effectively guarantees the death of both babies? Dr. Koop felt that surgery was the only right course in this situation. The hospital sought a legal opinion as well as advice from the Catholic Church; both agreed with Dr. Koop. The family, being Orthodox Jews, consulted Reb Moshe.

Dr. Koop prepared his surgical team and waited for Reb Moshe’s response.

As reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer of October 16, 1977, and recounted in ASIA Vol. IV, February 2001, Reb Moshe spent four to five hours every night for eleven days in intense halachic deliberation, ultimately concluding that the surgery was permitted.

The surgery saved Baby Girl B’s life, but she unfortunately died three months later from complications of liver failure and infection.

Fusing Compassion and Truth

R

eb Moshe’s status involved him in many sensitive cases, and sometimes he suffered personal aggravation or attacks as a result. Someone asked him: “Why does the Rosh Yeshivah allow himself to get involved in such cases?” Replied Reb Moshe, “Had you seen the tears of the person who brought the problem before me, you would not have asked such a question” (Rabbi Shimon Finkelman, Reb Moshe, Mesorah Publication, 19986, p.106–107).

Indeed, some perceived Reb Moshe’s uniqueness as lying in his compassion. Rav Michel Berenbaum expressed it in this way: “Reb Moshe was the man of halachah, but from seeing his teshuvos, one cans see the chesed [kindness] and concern he felt for others.” Reb Moshe himself, however, did not see it that way at all. To him compassion and truth were synonymous. Someone close to Reb Moshe was once sent to ask him a halachic question with an unusual request — to tell the Rosh Yeshivah that the person wants a decision that is strict halachah without any leniencies. “I do not rule with lenience,” replied Reb Moshe. “I rule according to the law.”

Compassion notwithstanding, Reb Moshe stood his ground when he was convinced of the correctness of his position. Reb Moshe put great effort in ensuring that his teshuvos be well based and he consulted experts when he needed to understand the medical facts. He first wrote out the draft of a teshuva on a piece of stationery, then recorded it in a composition notebook, then copied it into a big ledger, and finally reviewed it and sent the final copy for publication with notes and additions in the margins. Dr. Zelefsky recalls that he cites Dr. Stanley Boczko, a frum urologist, in one of his teshuvos pertaining to prostate surgery (Even HaEzer 4:28–32).

Reb Moshe understood that his decisions received wide hearing and wielded great influence. He took a broad view of issues and considered all angles. A good example of this is his teshuvah on smoking. In 1964, the surgeon general of the United States issued a report that pronounced smoking to be dangerous and recommended smoking cessation. Reb Moshe carefully analyzed the evidence and concluded that although it is proper not to smoke, one cannot say that smoking is completely prohibited because many people still smoke and therefore, the Talmudic principle, “the L-rd protects the fools” applies to smokers. However, Reb Moshe also saw here another issue — an issue of disrespect. He writes that many rabbinic scholars of past generations as well as those in our own time do smoke and will continue to do so irrespective of what he might say. Although he did not say so explicitly, those close to him understood that he felt that prohibiting smoking would lead to a disrespect for these rabbis and rabbis in general (Yoreh Deiah 2:49). [Some argue that now that the dangers of smoking are better known and few people smoke, Reb Moshe would now prohibit it completely.]

On the other hand, Reb Moshe was also sensitive to those exposed to second-hand smoke. Dr. Rosner reports that Reb Moshe ruled that those who smoke in public and cause discomfort or headache to nonsmokers are considered mazikim, people who inflict damage on others, and smokers cannot smoke in places where the community davens or learns, even if only one person objects. This psak has been widely accepted in the yeshivah world.

Dr. Zelefsky remembers the sensitivity and graciousness that Reb Moshe always displayed. “One time, I went down to the Lower East Side to ask him some medical halachah questions and I met Reb Moshe after Minchah. As we were walking out, Reb Moshe suddenly reversed his steps and went back to his shtender and began to rummage inside it. I stood watching incomprehensively, but of course I did not say a word. He turned around and walked out again alongside me, clutching something that I could not see.

“There was a beggar sitting at the exit door. Reb Moshe stopped and spoke pleasantly with him, inquiring after his health and circumstances. He then offered him a heartfelt handshake of “Sholom Aleichem,” unobtrusively pressing dollar bills into his hand.

“This was Reb Moshe,” concludes Dr. Zelefsky, “always a mentsch, always pleasant and gracious to all people, the great scholar that he was notwithstanding.”

Many years later, Reb Moshe underwent an X-ray that raised alarm bells in his doctor’s mind. “I reviewed it together with an old film and saw the same thing there, which was a relief,” Dr. Zelefsky remembers, “since it meant that this was most likely a benign finding. At the same time, a CT scan was clearly indicated. I was not going to take any chances. I arranged a whole medical team headed by a frum cardiologist to stand by as Reb Moshe underwent the procedure. Unfortunately, Reb Moshe was delayed in traffic and after he started the test and everything was proceeding fine, I had to leave to tend to other matters.

“An hour later I was paged. Reb Moshe had completed the procedure but refused to leave. He asked to see me in order to personally thank me. Never mind that I was his student and he was the gadol hador. Reb Moshe could not envision leaving without showing hakoras hatov (gratitude) — this was the kind of superb mentsch that he was.”

“He Left Us Many Legacies”

H

ow can one assess the legacy and influence of a gadol hador? It is difficult to encompass and summarize Reb Moshe’s contribution merely in words. In the field of medical halachah at least, we can echo the words of Dr. Rosner: “He gave us the ability to practice medicine as Torah-observant Jews. He was practical and pragmatic, understanding and sensitive, knowledgeable and close to earth. He was never timid. His answers to us were clear, concise, precise, and to the point. His answers adhered scrupulously to the laws of the Torah but also were in keeping with the highest standards of medical practice. All these years he was our guide and inspiration, and his memory lives on in our hearts and our minds” (F. Rosner, Pioneers in Jewish Medical Ethics, p. 97).

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 349)

Oops! We could not locate your form.