Hail to the Chief Rabbi

| July 23, 2024Rav Yitzchak Isaac HaLevi Herzog: chief rabbi of Eretz Yisrael under the British Mandate, and first chief rabbi of the State of Israel

Title: Hail to the Chief Rabbi

Location: Jerusalem

Document: Southern Israelite

Time: 1937

It goes without saying that during those days [leading up to and during World War II and the Holocaust], the eyes of millions of Jews worldwide turned to the home of the chief rabbi in Yerushalayim, with requests for assistance, sagacity, and comfort, in the manner that the Jewish People have historically turned towards gedolei Yisrael in times of adversity and distress.

As in the days of Rav Shmuel Hanagid, Don Yitzchak Abarbanel in Spain, Menashe ben Israel in Holland, and Rav Yitzchak Elchanan Spektor in Kovno, all of whom in previous generations knocked on doors of various government officials, European kings, and leaders, to attend to the needs of their people, so too the chief rabbi, Rav Yitzchak Isaac HaLevi Herzog trekked from one government office to another, begging for assistance on behalf of his beleaguered nation in grave danger.

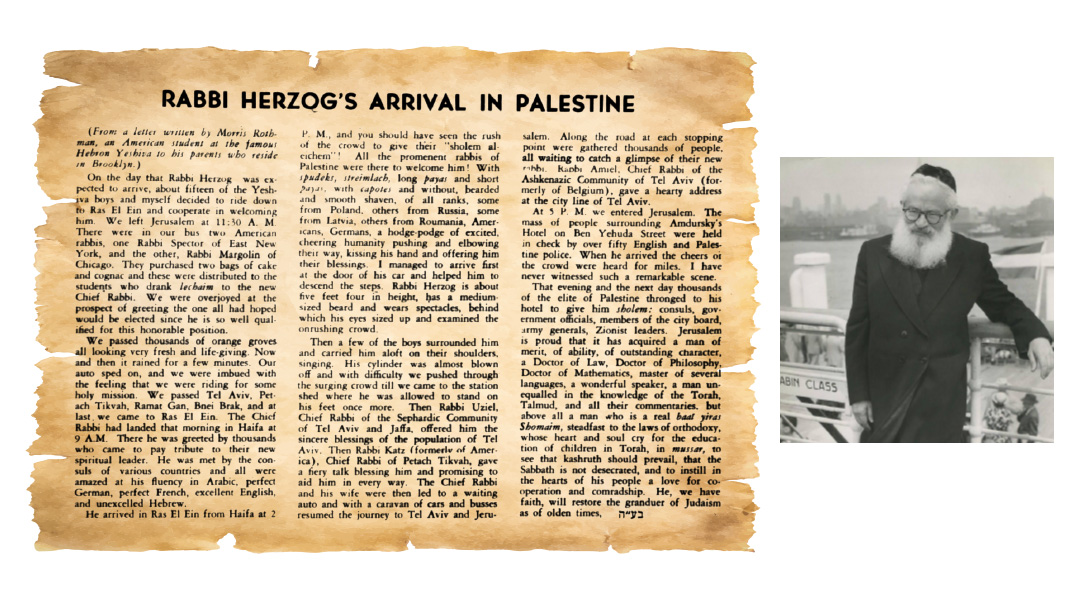

—Rabbi Aharon Benzion Shurin

From 1916 to 1936, Rav Yitzchak Isaac HaLevi Herzog (1888–1959) enjoyed a relatively quiet and lucrative rabbinical career in Ireland. As chief rabbi of Ireland, he maintained close ties with the government, supported the Irish War of Independence, and did much to oversee religious life in Ireland. In stark contrast to the tranquility of Dublin, his career as chief rabbi of Eretz Yisrael under the British Mandate, and first chief rabbi of the State of Israel coincided with likely the most tumultuous two decades in Jewish history. Succeeding Rav Avraham Yitzchak HaKohein Kook in 1936, he served in that capacity until his own passing 23 years later.

Shortly after he assumed his post, the Great Arab Revolt broke out, and in the ensuing political turmoil, the British issued the infamous “White Paper,” severely curtailing Jewish immigration to Palestine. Rav Herzog led a large demonstration against the draconian anti-immigration policy, and dramatically ripped a copy of the White Paper to shreds. Decades later, his son Chaim Herzog was serving as the Israeli ambassador to the UN when Resolution 3379, declaring that “Zionism is racism,” was adopted. Chaim Herzog echoed his father’s action by tearing the resolution in half from the podium.

When World War II broke out in September 1939, Rav Herzog tirelessly engaged in rescue efforts, establishing the Vaad Hayeshivos in 1940 and investing prodigious efforts in rescuing rabbis and yeshivah students from war-torn Europe. Despite the naval battles in the Mediterranean and Atlantic, he traveled to England and the US during the early years of the war, to beg diplomats and government officials to grant visas to desperate Jewish refugees.

Following the war, he embarked on another long and arduous journey to inspire survivors in DP camps in Germany, breathe new life into survivor communities in Poland, and try to rescue surviving Jewish children who had been hidden in monasteries throughout Europe during the war. The latter effort met with limited success, despite Rav Herzog pleading his case in a personal audience with the pope.

Serving as the first chief rabbi of the nascent State of Israel presented a whole new slew of challenges. Building a national infrastructure for the rabbinate, determining the role of the rabbinate and halachah in the mechanisms of the state, and navigating the delicate relationship between various demographics of the largely secular population and religious factions, some of whom didn’t recognize the office of the chief rabbinate, were just some of the tasks he gracefully and tactfully handled during this time. He exhibited leadership in areas of halachah that had no tradition or precedent, including regulations for a Jewish army, and kashrus and Shabbos in government institutions.

His initial appointment to the chief rabbinate was a contentious election, as the close talmid of Rav Kook, Rav Yaakov Moshe Charlap, was the leading candidate. However, Rav Chaim Ozer Grodzenski of Vilna, the Chazon Ish, and several other Torah leaders backed the candidacy of Rav Herzog, who was ultimately elected.

Despite the prominence of his office, Rav Herzog exuded modesty when halachic disputes arose within the rabbinic world. He never insisted that his position be followed due to his position as chief rabbi. He’d often remark, “We Jews don’t have a pope,” and that the chief rabbi was no more of a voice than any other posek. He’d often consult with other poskim on weighty issues, and carried on a flourishing correspondence with Rav Chaim Ozer until the latter’s passing in 1940.

Rav Herzog’s personal home in Rechavia was a veritable beis vaad l’chachamim. Many rabbis and yeshivah students would frequent his abode, where he’d revel in engaging them in Torah discussions. Once he was “talking in learning” with a young yeshivah student when he received a message that the secretary for the high commissioner for Palestine, Sir Harold MacMichael, had arrived with a message.

Rav Herzog stated, “He can wait a bit. It’s okay if he waits until we’re finished with our Torah discussion.”

Most memorable were the weekly Friday morning meetings with Torah sages in his home on Rechov Ibn Ezra. Many eyewitness accounts survive, describing in great detail the vibrant pilpul and pure joy that permeated the room, as seforim opened, voices raised, and the entire room was electrified with the exciting discussions covering the gamut of Torah literature.

Among the participants in the weekly Friday meetings were Rav Herzog’s father-in-law, Rav Shmuel Yitzchak Hillman; Rav Isser Zalman Meltzer; Rav Yechiel Mechel Tikochinsky; Rav Eliyahu Reem; Rav Yerucham Warhaftig; Rav Shimshon Aharon Polanski; Rav Gershon Lapidos; Rav Reuven Katz; Rav Yaakov Klemes; Rav Shlomo Zalman Auerbach; Rav Sholom Schwadron; Rav Yosef Shalom Elyashiv (Rav Herzog personally arranged for his position on the Rabbanut beis din); Rav Ovadiah Hadaya; Rav Yaakov Ades; Rav Eliezer Goldschmidt; Rav Shlomo Shimshon Karelitz; Rav Yehuda Gershuni; Rav Avraham Shapiro; Rav Shlomo Goren; Rav Betzalel Zolty; Rav Binyamin Zilber; Rav Eliezer Waldenberg; Rav Yisrael Grossman; and many others.

The Chief Rabbi and the Ridvaz

In 1910, the 22-year-old Rav Herzog seized an opportunity when the Ridbaz, Rav Yaakov Dovid Willowsky, visited London. After a grueling seven-day ordeal, during which the Ridbaz tested Rav Herzog on nearly every facet of halachah, he granted him semichah. Concurrently, during a fundraising visit to the city, the Telzer rosh yeshivah, Rav Leizer Gordon, suffered a fatal heart attack. Rav Herzog attended the funeral, where his future father-in-law, Dayan Hillman, and the Ridbaz both delivered memorable eulogies.

Doctor of Porphyrology

In addition to his Torah education and vast knowledge, Rav Herzog studied at the Sorbonne in Paris and University of London, where he received his doctorate in 1914. His thesis was on the color techeiles and identifying the elusive chilazon that produced the techeiles ink. For the purposes of his doctorate, Rav Herzog coined the term “Hebrew porphyrology.” Displaying a mastery of Talmudic sources, Midrashic texts, and general knowledge, Rav Herzog — who was proficient in 12 languages — displayed a mastery of archaeology, chemistry, ancient literature, philology, and marine biology. His pioneering research on the topic of techeiles, and assessing the possibility that the chilazon was a sea snail, remain the benchmark of research on the subject until today.

This Thursday, 19 Tammuz marks the 65th Yahrzeit of Rav Yitzchak Isaac HaLevi Herzog

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1021)

Oops! We could not locate your form.