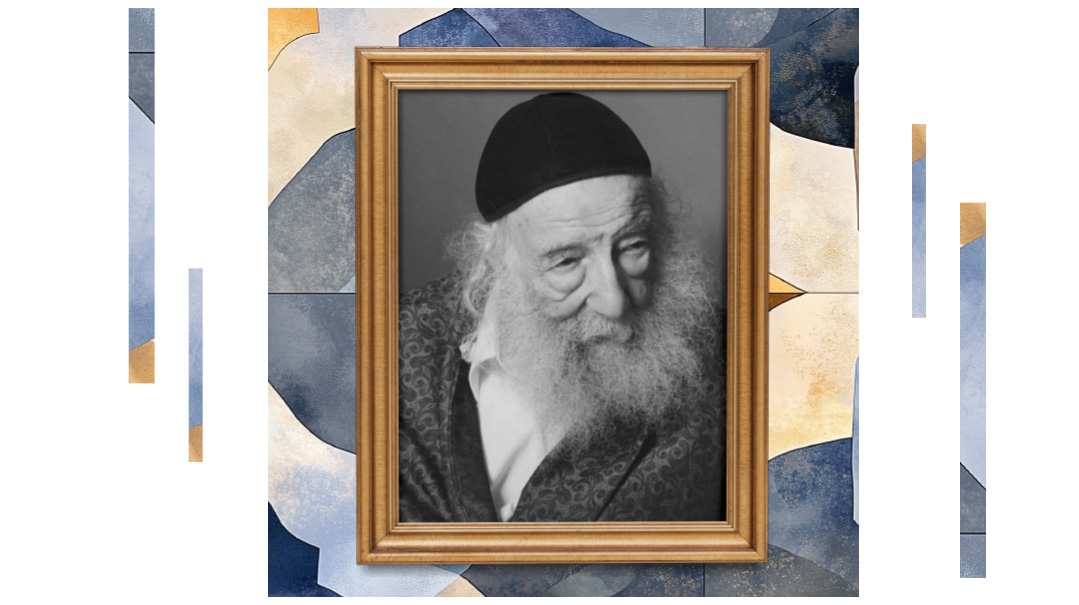

Haifa’s Rebbe of Unity & Peace

When Rav Eliezer Hager ztz"l was appointed Rebbe of Seret-Vizhnitz, he vowed to keep Yiddishkeit alive in “Red Haifa” at any cost

Photos: photos Aharon Baruch Leibovitz, JDN, Mishpacha archives

He was a child in the court of his illustrious grandfather, the Ahavas Yisrael of Vizhnitz, but stayed on the sidelines during the leadership of his father, the Mekor Baruch. Yet when he was appointed Rebbe of Seret-Vizhnitz 51 years ago, he vowed to keep Yiddishkeit alive in “Red Haifa” at any cost. Several years ago Rav Eliezer Hager ztz”l granted an exclusive interview to Mishpacha, sharing his convictions about a country in trouble and the remedy for healing

O

n Motzaei Yom Kippur 1924 in Grosswardein, Transylvania, the Ahavas Yisrael of Vizhnitz couldn’t contain his joy.

A new grandson had just been born to his son Rav Baruch Hager and Rebbetzin Tzirel — and named Eliezer after Rav Baruch’s uncle Rav Eliezer of Dzikov. Later, looking at the newborn, the Ahavas Yisrael exclaimed, “When my grandfather, Rav Naftali of Ropschitz, beheld his newborn son, Rav Eliezer of Dzikov, he said, ‘Eliezer, my son, you are shining like the sun!’ ”

Years later, it was obvious that the Ahavas Yisrael was referring to this newborn Eliezer as well. He was to become the Seret-Vizhnitz Rebbe of Eretz Yisrael, and in the 51 years of his influence until his passing last week at age 90, helped turn notoriously “red” Haifa from a staunchly secular town to a city that was open to the embrace of Torah and chassidus.

The Ahavas Yisrael passed away in 1936 when Eliezer was just 12, but even as a young child, he was unusually attached to his grandfather. One time, he accompanied the Ahavas Yisrael to the “kvittlach tzimmer,” the Rebbe’s private domain where he received visitors in confidence. The Rebbe’s attendants tried to stop the child at the door. “Leave the boy,” the Rebbe ordered them. “Let him watch. The day will come when many people will gather at his door.”

Of the four rabbinic heirs of the Ahavas Yisrael — Rav Menachem Mendel of Vishive (who died in a Klausenberg hospital in 1941), the Imrei Chaim (Rav Chaim Meir) of Vizhnitz, the Damesek Eliezer, and the Mekor Baruch — the last three survived the war and eventually made it to Eretz Yisrael. While the Imrei Chaim and the Mekor Baruch were still in Europe, Rav Eliezer — who had been able to retain an intensive Torah regimen while on the run from the Nazis — came to Eretz Yisrael in 1946 and was interned in the Atlit detention camp by the British. His uncle, the Damesek Eliezer of Vizhnitz (who passed away soon after), heard about his arrival and managed to smuggle him a note with a brachah for success in Eretz Yisrael. After being freed from prison, the future Rebbe trained with the Haganah pre-state militia, and was even wounded during active combat in the War of Independence, where he served as a tank commander.

Meanwhile, the Imrei Chaim and Rav Baruch were in Antwerp at the time of their brother the Damesek Eliezer’s passing, and it was time for them to make their choices to ensure the continuation of the chassidus. The Imrei Chaim, the oldest remaining brother, offered Rav Baruch a choice: Either Rav Baruch would travel to Tel Aviv to lead the Vizhnitzer chassidus there, while the Imrei Chaim would settle in the United States, or the Imrei Chaim would go to Eretz Yisrael and the Mekor Baruch could make his way to America.

The Mekor Baruch replied fervently, “Chas v’chalilah! I will not be the cause of your remaining in the Diaspora. You go to Tel Aviv, and I will take up residence in a different city.” That city was Haifa, which was utterly devoid of kedushah at the time. Over the years, the Mekor Baruch built his modest chassidic empire there, which went on to grow and expand over the years of Rav Eliezer’s leadership following the Mekor Baruch’s passing in 1963.

Holiness in Haifa

Throughout his father’s life, Rav Eliezer refused to don the cloak of rabbanus, and went out to work for a living. But when Rav Baruch, leader of the Seret-Vizhnitz chassidus in Eretz Yisrael (named after the community where he’d been rav before World War II) passed away, he left behind a small yet deeply unified community that was desperate for a leader. The chassidim viewed Rav Eliezer as the Mekor Baruch’s natural successor, even though he’d done his best to avoid public attention during his father’s lifetime.

The older chassidim still remember their surprise when, immediately after the Rebbe assumed the mantle of leadership, his incredible character was revealed. Suddenly, they were exposed to his paternal kindness, his exceptional hasmadah, his vast Torah knowledge, and his sensitivity and appreciation for every Israeli, chareidi or secular. Under his sagacious and merciful leadership, Seret-Vizhnitz became what it is today, in accordance with the unique path laid out by its warm, kind, yet ideologically staunch rebbe — a one-time IDF soldier who understood the nuances of the complex society around him. It’s an empire of chassidus, but a real “out of town”-style chassidic court, where all types of Jews feel welcome and where the Rebbe’s own chassidim have been trained to welcome others who are not exactly like them.

The chassidim of Seret-Vizhnitz talk about the tremendous love and admiration that existed between the Rebbe and his brother, Rav Moshe Hager ztz”l, the rosh yeshivah of Seret-Vizhnitz. Even though the chassidus could easily have split into two streams, as did many other chassidic groups, the two brothers preferred to carry on their father’s legacy together, with the Rebbe leading the community and his brother heading the yeshivah. Their relationship served as a surprising and inspiring model of cooperation. Their famous dance at the simchahs of their children — the “brider tantz” — was not only a display of unity, but an important lesson to all who saw them.

The Rebbe felt a tremendous sense of responsibility for the Jewish character of Haifa, carrying on his father’s dream of a chareidi presence in the city. When the Lev Simcha of Gur stopped sending avreichim to live in Haifa and instead began directing them to other cities, the Seret-Vizhnitz Rebbe paid a visit to the Gerrer Rebbe in his home, imploring him to continue sending chassidim to the city. The Rebbe emphasized that his father, the Mekor Baruch, had dreamed of a strong Torah presence in Haifa. Why halt those efforts? The Rebbe, for his part, was never partisan. He would do his utmost to help any chareidi group expand in the city, even if it wasn’t specifically in the interest of his chassidus.

Rav Eliezer of Seret-Vizhnitz was always known to steer clear of discord and controversy, especially when it caused chareidi society to divide into different camps. Seret-Vizhnitz always remained free of “l’sheim Shamayim” politics. “Holy wars” never penetrated the neighborhood of Ramat Vizhnitz in Haifa. The chassidim won’t easily forget the volatile elections of 1988, when Agudah and Degel HaTorah split chareidi Israeli society down the middle. At that time, the Rebbe — an Agudah activist for decades — announced, “We don’t belong to any party.”

But while steering clear of controversy was imperative, so was showing up on time for everything else. One of the most fascinating things about the Rebbe’s leadership was his rigid regime of timeliness. The Rebbe trained his chassidim to be governed by the clock, and he set a personal example, running a daily schedule rigid to the point of mesirus nefesh. Everyone in Seret-Vizhnitz knew that he could set his watch by the Rebbe as he left his home for the beis medrash, where the Rebbe would be seated exactly two minutes before davening. This idea of kedushas hazeman became the watchword of the kehillah. There was a big event the night before? There’s something unusual scheduled for tomorrow? It makes no difference. As the Rebbe often said in his shmuessen, “When a person is organized in every way, when he has set times to go to sleep and to get up, to daven and to learn, then his spiritual life will also be blessed with success.”

Exclusive from the Rebbe

And just like the Rebbe wasn’t afraid to say what had to be said to ensure the strict daily regimen of his chassidim, he wasn’t afraid to deal with the difficult, controversial issues that face chareidi and Israeli society at large. Not every rebbe wants to take on issues that might not directly affect his flock, but for the Seret-Viznhitz Rebbe, what affects one group affects all of Klal Yisrael. Outspoken and fearless as he was, he granted me an exclusive interview in the summer of 2006, just after Israel fought the Second Lebanon War on its northern front.

“The people in this country,” the Rebbe told me, “do not sufficiently understand the existential nature facing the Jews of Eretz Yisrael. Our leaders don’t understand the situation at all. I don’t want to say a bad word about them, but we need tremendous mercy from Hashem.”

A magnificent beis medrash building stands at the end of the winding road that starts at the main entrance to Haifa’s Ramat Vizhnitz neighborhood. To the left of the beis medrash stands the famous ramp leading to the apartment at Netiv Eliezer 5, the private home of the Seret-Vizhnitz Rebbe. When I arrived a few days before Rosh Hashanah, the ramp was filled with people — avreichim and their families — eager to enter the Rebbe’s chamber and receive his blessing for the new year. The Rebbe was already elderly and not in the best of health, but it didn’t stop him from cutting through the cloudiness that tends to obfuscate issues, even as his warm smile was disarming, his sparkling eyes filled with a love that seemed to communicate a profound understanding of every human being and the complexity of life that seems to consume us.

Our interview took place a few weeks after the Second Lebanon War, which the Rebbe — a resident of Haifa, which was in shooting range of Katyusha rockets — felt up close. Yet one year after a different war — last summer’s Operation Protective Edge in the Gaza strip — every word is as relevant as if it were spoken today.

“During the war,” the Rebbe said, “I refrained from voicing these ideas, but later, I told the chassidim that the decree of this war was a result of the feeling of ‘kochi v’otzem yadi.’ Between us, even in the religious and chareidi worlds, people felt that there was no reason to fear. They relied on the power of the IDF, on its advanced air force, its tanks, and all its state-of-the-art weapons to defeat the enemy.

“And what did we see? It was all in vain. It’s frightening to think about: Arab terrorists, without any state or clear source of power, humbled our country. They killed people, and for the first time in years, caused hundreds of thousands of Jews to be displaced from their homes and wander from city to city! Do you realize the defeat and degradation we suffered during this war?

“We have to uproot the feeling of kochi v’otzem yadi that has spread throughout our camp. The small consolation we have is that today, we all recognize the fact that our might alone is insufficient to vanquish our enemies. Only with the power of emunah and mesirus nefesh can we be victorious.”

Over the years, the Rebbe never hesitated to voice his opinions to Israeli government leaders who occasionally came to consult with him. The mayors of Haifa over the past 50 years, even those who were not particularly fond of the chareidi community and its rabbanim, all developed great affection for the Rebbe and his chassidim, often visiting to seek his advice and blessing.

When the idea of trading land for peace was first proposed in the 1980s, the Rebbe was pained by the eagerness of government officials to give away portions of the Holy Land, and was distressed by their disparagement of the pain of the settlers. After the assassination of Prime Minister Yitzchak Rabin and the succession of Shimon Peres to his post in 1995, Peres paid the Rebbe a visit, and was duly admonished about the government’s indifference to returning land. Even if officials speak about it, said the Rebbe, it should be discussed with sorrow and pain, not with a sense of denigration for all that is holy and precious.

The Rebbe felt that the country’s leadership is its worst enemy. “During the war, the prime minister [Ehud Olmert] remarked at one point that Israel does not need anyone’s help, and that the country can manage alone,” the Rebbe told me. “I have difficulty understanding this. What was the point of this arrogant statement? What place is there to make such remarks? Our leaders are off, and we need tremendous mercy.”

At the time, the Rebbe said he felt the proper thing to do would be for all the gedolei Yisrael to gather and brainstorm how to annul the decrees that endanger the continued existence of the Jewish People here. “We must assess what to do in the future. The situation is awful, and we must come up with a plan to extricate ourselves,” the Rebbe said. “One thing we must do is speak the truth, in the clearest possible way.

“The mayor of Haifa, Yonah Yahav, comes to me sometimes to discuss issues,” the Rebbe continued. “He was happy to report that he approved the construction of reinforced rooms in every apartment in Haifa. I told him, ‘Before the next war, we must be prepared with shelters that will protect us against an atom bomb.’ As I said, the political leaders must open their eyes and prevent the possibility of Iran obtaining a nuclear weapon. ‘I am afraid to think about that,’ Yahav told me, but I told him we have to consider that. Then he added that Iran will probably not obtain the nuclear bomb during his term as mayor. ‘That is the problem here in Eretz Yisrael,’ I said. ‘Every politician thinks only about his own term; he isn’t prepared to look beyond it.’ ”

What should we, mitzvah-observing Jews, do to prevent or sweeten the decrees? “We must strengthen our Yiddishkeit, our faith in Hashem, the unity within our own camp, and our mesirus nefesh for every clause in the Shulchan Aruch,” the Rebbe answered. “We must also bring back those who are far away from Yiddishkeit; that is considered redemption of the soul. But that’s not enough to overcome the physical danger. The Jewish People’s survival in Eretz Yisrael today is in danger. We must provide a natural response to these dangers, and not push it off with all sorts of irrelevant claims.”

The Rebbe, who always waved the banner of peace and abhorred discord, said that creating true peace among ourselves will avert evil decrees. “It’s forbidden for machlokes to exist among us. The time has come to uproot machlokes completely from chareidi society. My holy father invested tremendous energy in creating unity and peace. When he settled in Haifa, there were many different factions here, and my father worked in the most incredible way to unite them all. Every child should be taught how machlokes consumes those who are part of it. Division and sinas chinam are society’s greatest tragedy, consuming everything in their path.”

Time to Say Goodbye

About a week before his passing, as the Rebbe set out with his driver for some fresh air due to his deteriorating health, he suddenly asked his attendant to pull over to the side of the road. “Where are the children now?” the Rebbe asked, referring to the talmidim of the Seret-Vizhnitz cheder. The gabbai quickly telephoned the menahel and asked him to prepare the children for a visit from the Rebbe. Within a few minutes, hundreds of children had been assembled in the playground. They filed past the Rebbe, who greeted each one, lovingly caressing them as they passed by. In light of the Rebbe’s weakened condition, the visit was especially surprising.

Soon afterward, the Rebbe — who hadn’t been public in some time due to ill health — asked to receive the chassidim in his home, inquiring about their well-being and blessing each of them heartily. A week later, the chassidim realized that it was the Rebbe’s way of taking his leave. His sudden passing left his community shattered and grieving, but he also left them with a legacy — a charge for unity and for humility, the remedies for ensuring our survival in Eretz Yisrael and sweetening the harsh decrees. —

Aryeh Ehrlich and Aharon Rubin contributed to this report

(Originally featured in Mishpacha Issue 568)

Oops! We could not locate your form.