Growing Up

| March 7, 2023Frum girls have a unique road to adulthood

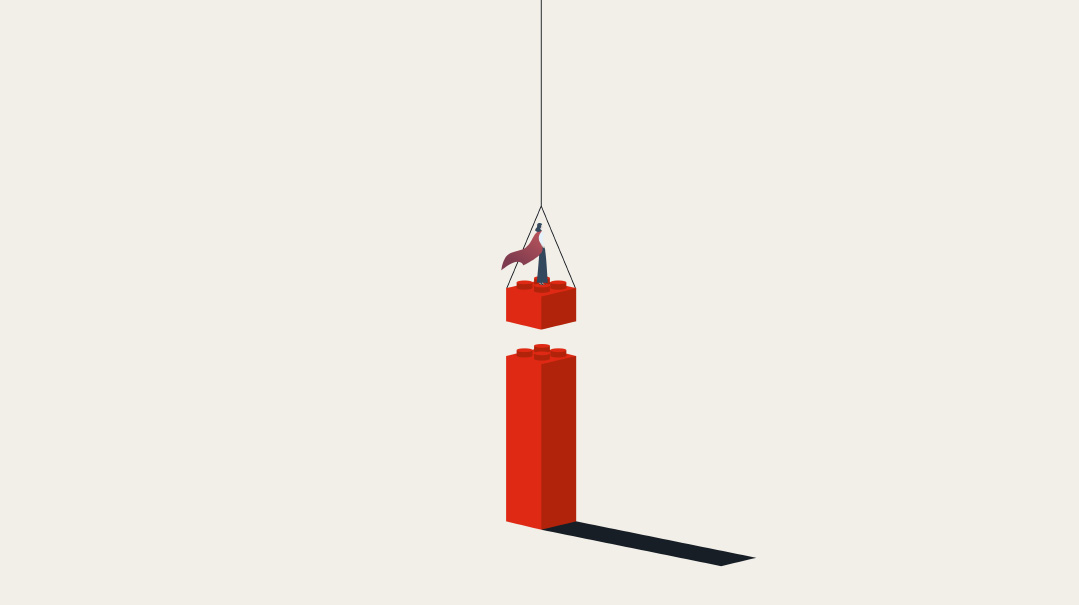

Becoming an adult is always a tumultuous process — all the more so for frum women, who are expected to make big decisions about dating, marriage, and their careers in a very short timeframe. This makes the road to adulthood unique for frum girls, realized Dr. Shira Kessler. Here, she shares the research and recommendations born out of a decade of her work

Chani’s Diary, April 2017

“You just don’t get it!”

I run to my room and slam the door. My parents never listen when I tell them what I want with my life. And why would they? Apparently, my life is completely planned out and I get zero say in it.

It all began with a simple comment. At dinner, Mom mentions that Mrs. Rubenstein’s daughter just got accepted into nursing school.

“How wonderful!” Ta says. “I bet her parents are proud. You know, Chani, nursing is a great career to help support your future husband and family….”

Yeah, if you enjoy biology and chemistry, which I don’t and never will.

“I’m sure they are,” I say, trying to keep my voice even. “She’s always had a passion for nursing, and should go into the field she’s passionate about, whatever that may be.”

“Chani, I know you want to be a teacher, but they don’t make any money!” Ta replies. “You’ve got to think about your future. Don’t come crying to me when you’re 35, debt-ridden, and deep into a life you can’t handle.”

I race to my room, trying to hold back my rage and my tears. It was hard enough figuring out what career I wanted to pursue, and now they don’t even agree with my choice. I’m expected to be an adult, but I constantly find myself being treated like a child.

I feel like the minute, no, the second I turned 18, the clock began ticking. You better know what you want to do for the rest of your life, and it must be chosen from the list of acceptable jobs. It’s almost like I was thrown into the pool of adulthood, and it’s swim… or sink.

A Safe Space to Share

I’ve sat across from hundreds of young women like Chani*, who are trying to make sense of the confusion, doubt, and turbulence they feel as they emerge into adulthood. My office is a safe space where they can talk about the most vulnerable parts of their lives.

During the initial session, we talk about why they’re here. Typically, it’s because they want clarity and guidance on how to better tackle the very real hurdles of adulthood. But even though my clients voluntarily sign up for therapy, they’re cautious, defensive, even skeptical.

“How can I trust you aren’t saying what I need to hear because I pay you for that?”

“You say all my feelings are normal, but are you just trying to be nice?”

“You mean other clients cry here? NO WAY. I’ll never let you see me cry!”

It usually takes a few sessions, but eventually, my clients will shed tears. The first time I see them cry, I look away to give them privacy. They’re not ready to completely reveal themselves yet.

Tears are a doorway in therapy. Crying is how they admit to me — but more so to themselves — that they aren’t all okay, that there is some pain. It displays the raw version of their feelings, rather than the “I’m fine” script they publicly announce.

Crying breaks down the barriers, moves us into the next level of trust, and gives me insight into their inner world. It shows me that they're now connected to their feelings, which will enable them to work through the pain. They’re now ready to look inside and find themselves. Each session opens a window to a deeper part of themselves.

No matter who the client is, they all ask the same question: why am I the only one who hasn’t figured it all out?

What they don’t realize is that it’s not just them. As a therapist, I’ve worked with countless young women who struggle with doubt, confusion, and insecurity as they try to create their futures. These years are replete with uncertainty, tumult, anxiety, instability, and disappointment.

The challenges of “coming of age” are age-old. But in today’s American culture, where delayed adolescence is the norm, making the transition from childhood dependence to independent adulthood is more of an uphill battle. There’s even a new word in the American lexicon to describe the process: adulting, which is when a person assumes the tasks, responsibilities, and behaviors traditionally associated with grown-up life.

Despite the prevalence of adulting challenges in the greater American culture, I noticed early on that there were unique obstacles facing frum young women.

I wanted to understand why, so while earning a PhD in clinical social work from Smith College, I focused my doctoral dissertation on the topic of emerging adulthood for young Orthodox women. Over the past decade, I’ve read all the peer-reviewed journal articles and presentations on emerging adulthood, studied the leading theorists; spoken with high school teachers and principals of seminaries in Israel and America; and gathered anecdotal data from singles and married individuals about their personal experiences.

A major difference emerged in my research: In Western culture, you might be considered an adult when you live independently from your parents, have an established career, and are in a committed long-term relationship. But the main markers that define adulthood for a frum female adult are different. There are four main categories, and the first is marriage.

Chani’s Diary, May 2018

At my cousin Shalvah’s wedding last week, all the married women my age were huddled together at the “married table.” All I could think was, I want to be in that huddle! I want a sheitel and a ring. I want the status and security of marriage.

I’ve been on plenty of dates, but nothing has clicked. When the shadchanim say things like, “You’re too picky,” my stomach twists. Aren’t I supposed to be picky about the person I’ll spend the rest of my life with?

Truthfully, I suspect I’m the problem. I don’t know what to do or say to find a husband and make it work. Oh sure, I get plenty of “helpful” advice: Be nice, but not too nice! Be attractive, but not attracting! Be smart, but not too smart!

But I keep messing up! Like with the last guy from Lakewood. I know I probably talked too much and laughed too loud, but that’s just how I am. Should I be a watered-down version of myself to “make it work”? I suppose it’s better to be married to anyone than to be an older single.

Meeting Yourself through the Shidduch Process

Emerging adulthood — typically defined as the years between 18 and 22, but up to age 29 — is a stage of self-exploration and identity formation. In American culture, this process is focused entirely on the self: What is the purpose of my life? What are my strengths and weaknesses? What’s my personality type? What do I value?

What my dissertation research revealed is how differently this process plays out for frum women. The identity development questions they ask themselves revolve entirely around dating, marriage, and family life: What type of spouse am I looking for? What kind of home do I want to build? What can I offer to a relationship? What career or job will fit in with my role as a wife and mother?

They then build their identity through the process of dating. Their “I” is formed based on their future “We.” Each date brings another opportunity for identity exploration: What did I learn about myself from that date? Or now that I’ve broken it off with him, I see that what I really need is someone with (fill in the blank) trait.

Each date forces them to reflect on what they want for their future: Do I want to live where he wants to, and will I fit into that community? Do I share his vision of a Torah home? Is this the level of religious observance I want to commit to? Is this the socioeconomic status I want? They discover themselves through discovering the differences in others.

The identity formation process is equally shaped by a lack of suggestions from shadchanim. It makes them question if something is undesirable about them and may lead to character growth and/or self-criticism (even if the dry spell is entirely unrelated to their inherent qualities).

The emotional rollercoaster of the waiting stage can give them a window into their inner worlds. For instance, what is their instinctive response to uncertainty? Is it anger, passive aggressiveness, depression, anxiety, jealousy, despair? Through the emotional turmoil, they gain awareness of themselves as parts of their identity are revealed.

Marriage is the defining marker of adulthood for frum women, but — beyond hishtadlus — it’s completely out of their control. And that’s what triggers much of the stress, pressure, and anxiety of this life stage. Indeed, the singles in my research study expressed frustration that the only way toward the completion of identity formation is through something they cannot do anything about. They also felt that the pressure to get married overshadowed the “finding yourself” aspect of this intertwined process. Worse, they feared that if they didn’t get married quickly, they’d never find their own unique identity.

What if, despite hishtadlus, a woman is still single at 29 or 39? Does that mean she’s still not an “adult”? That is, indeed, how many young frum women feel. As one research participant put it, “Marriage is like a certificate of adulthood, and the messaging from our society affirms this. Look at my sister: she’s five years younger than me, has less work and life experience, but because she’s married, she got a promotion before me. How can I feel like an adult if no one treats me like one? Putting a wig on my head will finally make people see me as an adult.”

Chani’s Diary, February 2019

Still dating, still single. I’m busy nonstop with college, and in the hours in between, I’m even busier. I keep getting calls to do favors and I feel like I can’t say no.

Need a volunteer to set up kiddush? Sure!

Desperate for a last-minute substitute? Sure!

Mentor a young girl whose mother has cancer? Sure!

How could I possibly say no? That’s what a Jewish woman does: she gives. She stretches herself to give to her family and community, even if it means she gets little sleep or has no down time.

The problem is, I’m having a hard time getting through this semester. I have an exam tomorrow, but I also agreed to watch my sister’s kids because “she’s going to lose it if she doesn’t get out.” I know my sister is having a hard time right now, and I’m trying to be sensitive to that, but when is it okay to put myself first?

Giving: Who You Are or What You Do

What’s undeniably unique about emerging adulthood for frum women is that “being a giver” is a marker of “being a grown-up.” In my study, women shared that you can’t be considered an adult if you’re not a giver — it’s a mandatory prerequisite.

Giving wasn’t defined strictly by acts of chesed, but also by emotional giving (such as being thoughtful, validating, and emotionally available). As one study participant expressed it, “If you’re not kind, sensitive to other’s feelings, and involved in chesed, you’re not a fully developed person.”

The prevailing belief was that through giving, a Jewish woman’s identity is born. Women felt pressured to choose a field of work that serves others but also pays enough to provide for a family. Many women defined their worth based on their level of giving.

Typically stress, anxiety, and guilt arose in the following circumstances:

When they couldn’t give what was expected of them.

When they weren’t actively involved in giving.

When there was no one to give to.

When they felt their giving wasn’t enough or within the accepted standard.

Instead of giving being an action — something they do — it was viewed as a core part of their identity — who they are. And since giving was seen as a gateway toward identity formation, many women had a difficult time saying no or setting and enforcing boundaries. As one participant wrote, “An adult woman gives in to avoid conflict, and a part of giving of yourself is not always having your own way.”

The only form of giving that study participants felt extremely uncomfortable with, was giving to themselves. This made them feel selfish or weak in some way. Similarly, being a “taker” (aside from permissible acts of taking, such as accepting help from family) was associated with being needy or being a burden to others.

Chani’s Diary, December 2019

Still dating, still single. I desperately want a happy family with a beautiful home. But I can’t do anything to speed up the process. Nothing is in my control. So today, I decide to control what I can: my body.

I begin measuring my value by the number on the scale, the height of my heel, and the color of my nails. I force myself to look put-together to hide the fact I’m nowhere near put-together inside.

If I look good, no one will question me. I’ll fit in and find someone to marry me.

“No, thank you, I’ll pass on dessert.”

Smile and nod. Be an eishes chayil.

Whatever the latest style is, buy it.

Repeat after me. You are happy! No negative emotions allowed. Inner thoughts stay inside. Great job!

Fronting an Image

Looking put-together doesn’t mean you are put-together, but study participants felt projecting a put-together look sends a signal to the world that they’re ready for adulthood, which in turn makes people treat you more like an adult. This was considered a third marker of adulthood.

The definition of “put-together” went beyond dressing in style. It also meant being thin enough — weight was perceived as a symbol of how desirable, productive, lazy, healthy, undisciplined, or motivated one is. Women of all sizes mentioned a tremendous self-pressure to reach a certain acceptable weight. The general consensus was: “How I appear is more valued than who I am.”

Another status symbol of “put-togetherness” was spending money: purchasing expensive or designer items, going out to eat, having lavish parties, giving generously to tzedakah campaigns, traveling with friends, and so on. Spending was linked to generosity, or “being a giver.” It was not connected to financial independence, since what is stressed is appearing wealthy versus having wealth.

Many study participants felt a pressure to appear “flawless.” They felt that displaying imperfection — like sadness or struggle — meant they had not achieved adulthood. So they worked hard to only display happy and upbeat emotions. As one participant wrote, “I feel like I live two lives: the one I show, and the one I feel.”

With so much emphasis on “appearing” good, participants felt they didn’t have energy left to focus on “being” or “doing” good. Many were aware of the shallowness and emptiness of image, yet still felt the need to continue fronting a facade until they were married.

It’s important to emphasize that even though these markers of adulthood — marriage, “being a giver,” and image/appearances — exist societally, many of the research participants recognized that these aren’t what makes a person successful in adulthood. Rather, these were identified as “socialized markers” that must be attained because they symbolically display to the world that you’re an adult and will cause others to treat you accordingly.

The only marker that displays one’s maturity and competence in adulthood is the fourth: independence.

Chani’s Diary, September 2020

Finally, finally — I’m getting a real paycheck!

But here’s the weird part: It’s my own money, which I worked hard to earn, but it’s still hard for me to just enjoy it.

Everyone keeps telling me: save, save, save for when you get married. And I get it: I don’t know how people afford their lifestyles. But I can work my entire life! Can’t I just take a break, travel with my friends, and have a car to drive to 7/11 at 11 p.m. to get Slurpees?

Every time I purchase something, my mind ping-pongs:

This is a waste of money. Do you really need this? But wait, when else will you enjoy it?

Buy this dress — let yourself splurge a little! Except, wait… are you setting a standard for your younger siblings? Should you be a good role model and save more?

On and on it goes. It’s always pleasure now versus pleasure later.

The worst part is that there’s no right answer. No one can tell me the right thing to do. I have to figure it out for myself.

Finding Your Own Way

What Chani is experiencing — the constant questioning, the weighing of desires versus values, taking ownership, considering accountability — is the fourth marker of adulthood: independence.

Many Americans associate the word independence with young adults who are financially independent or live separately from the family unit. Neither apply to frum young women. Since it’s common for frum adults to be financially supported by family, financial independence was not considered a prerequisite for adulthood. Also, in frum culture, strong ties to family are embedded in the value system — frum women don’t seek independence from family, but rather interdependence.

So how did the research participants define independence? It was the ability to be independent in thoughts (not swayed by everyone else’s opinion), decisions (to think practically about the long-term impact of a decision), emotional regulation (to display self-control with impulses and mood), interdependence (knowing when and how to involve family members), and stability (even after high-stress experiences, to return to a solid baseline of healthy functioning).

One participant defined adulthood this way: “It’s the ability to think deeply about yourself and your life, and make positive choices as a result.”

Much of the work that’s done in therapy is focused on this. I listen to my clients as they sit on my couch, lamenting and questioning. I hear about their struggles, doubts, and triumphs. I feel their pain with them, and I give permission to their feelings, stories, and reactions. I often find myself reaffirming, “No, you are not crazy for feeling this way.”

I tell my clients, “You’ve been shown how to be a desirable ideal adult and how to achieve your goals quickly. You’ve been told what to say, how to look, and how to get the life you want. You’ve tried to make yourself fit in to be considered good and acceptable, and guaranteed a successful, happy life. But I don’t hear your voice in all of this. What you have been told may work for you. If it doesn’t, that is also okay. Let’s find a way for you to be you within it all.”

My office is a holding place, a building place, an “adulting” place. I give my clients tools and skills, but more importantly, a safe relationship that brings about their emergence. I help them step out of the chaos of their thoughts and observe from a healthy distance. I teach my clients that conflict is a tool to get to know yourself and to appreciate the differences between people. They learn how to accept limitations in themselves, their parents, and in others.

From their pain and their failures, they grow. They learn how to be comfortable with discomfort and to take themselves seriously even when others don’t. They stop fighting against life, and instead identify what they value most. Instead of being consumed by worry or “what ifs,” they learn to take one decision at a time. And slowly, decision by decision, they mature and emerge into their authentic adult selves.

Primer for Parents

In my therapy practice, I meet with young adults, but also their parents. The more parents understand what their daughter is going through, the better they can support her. Here’s what I wish every parent of an emerging adult knew:

Give Her Space, but Keep the Connection

The primary question of emerging adulthood is: Who am I? This process, called “individuation,” is when a young woman dissects all the identities that were given to her throughout childhood and adolescence, and chooses an identity that feels right for her. In doing so, she establishes an independent sense of self. Even when emerging adults choose to follow a familiar path that they grew up with, they cannot feel they are simply an extension of what they grew up with — they still must go through the process of choosing it. To develop and learn about themselves, young adults ideally need both distance and connection from parents. So the key is to give space while still maintaining a solid line of communication.

Create a Safety Net

A prerequisite for the individuation process is having a safe, stable relationship. A person can only grow, explore, and flourish when they have a safety net of a stable relationship to rely on. This can be a parent, mentor, therapist, friend, teacher, sibling, or other relative. For the relationship to qualify as safe, there must be consistency, real acknowledgement of the young woman as she is, trustworthiness, acceptance, nonjudgement, and availability.

People who experienced childhood trauma often struggle with adulting, because symptoms of trauma typically reappear as people try to figure out their futures. It’s very common — and highly recommended — for young adults to resolve trauma symptoms in therapy before marriage.

Let Her Choose

During the teen years, children are dependent on authority figures for approval, self-esteem, rules of conduct, and regulation. As young adults, they transition to getting these needs met from their own selves. To build muscles of self-reliance and autonomy, give your child opportunities to take charge, and give them room to make mistakes. Through choosing, they see the outcomes and gain experience for future scenarios. This helps them learn to trust themselves.

Expect a Little Rebellion

Whether a child acts out in a small way (like disagreeing with a parent’s opinion) or a big way (like leaving the family’s belief system), rebellion is a part of the individuation process. This can cause parents anguish and strain the parent-child relationship at a time when it’s needed the most. It’s important to recognize that the rebellion is not personal — it’s a rebellion as an attempt to build a unique identity.

Young adults are also vocal about their own parents’ “failures” in chinuch. Again, this is part of the process. They are trying to figure themselves out by reflecting on their childhood experiences.

If you’re feeling short on compassion for your daughter, go back in time and remember what you were like at her age. Try to be open and share with her. It may surprise you, but despite all appearances of rebellion or anger, there’s nothing more reassuring to emerging adults than getting their parents’ approval.

Anticipate Mixed Messages

Young people want the best of both worlds — to rely on themselves, while also still relying on their parents. Parents often struggle with requests like this from young adult children:

“Let me use the car, but don’t tell me who to hang out with.”

“Host my friends for Shabbos, but don’t talk to them.”

“Pay for my therapy, but don’t ask me what I spoke about.”

As a parent, it’s important to know your boundaries so you don’t feel taken advantage of. But recognize, too, that these conflicting feelings are a foundational part of the maturation process. It’s entirely normal for emerging adults to flip between extreme emotions: grief, as they mourn the loss of their childhood, followed by exuberance about their newfound independence. You’ll notice an increase in ambivalence and indecisiveness, as well as anxiety about the many responsibilities they must now manage. Expect rants, too, about the unfairness of things.

Empathize with Her Friendship Woes

To survive the adulting stage, women need solid friendships. But in the frum world, there are constant shifts in friend groups because some women get married earlier, and others get busier with academic or work responsibilities. As the individuation process happens, women also naturally drift closer or further from previous friends. This all adds to the list of shifting things in their lives, and can lead to boredom, or more often, loneliness. A friendship vacuum can be painfully acute, so parental empathy goes a long way.

Prepare for Power Shifts

As grown children mature, the power dynamic in the parent-child relationship undergoes a transformation. There’s a natural shift from an authoritative relationship to a mutual one. Prepare for a learning curve and growing pains as you both adjust to the new relationship dynamic.

Dr. Shira Kessler is a therapist based in Monsey, NY who specializes in helping unsettled young adults find their place and pace while setting a firm foundation for their futures.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 834)

Oops! We could not locate your form.