Green No Deal

| February 11, 2025On their frigid Danish island, are Greenlanders interested in jumping ship?

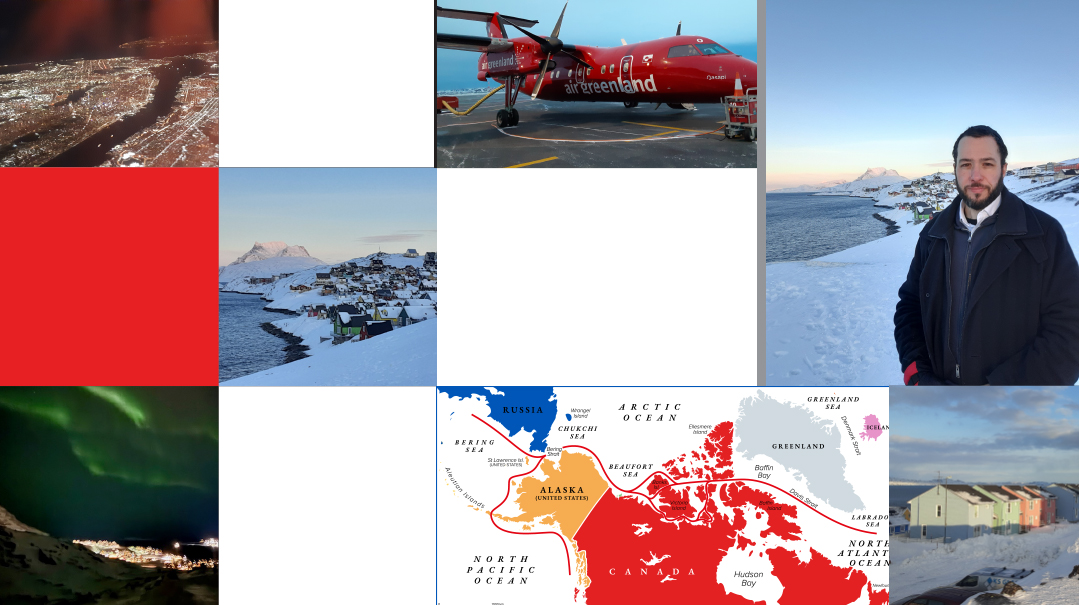

Text and photos: Yitzchok Landa, Greenland

Despite proud Greenlanders chafing under Danish rule, the idea of President Trump annexing their country to the United States isn’t very appealing to most. But like with many things the president is intent on accomplishing, the Greenlanders’ feelings may not be enough to stop him

I'm walking down the snow-covered streets of Nuuk, capital city of Greenland, when a shiny SUV roars ahead of me, pulls a hard left turn, and stops short, fishtailing on the icy road. The driver rolls his window down and I suppress a smile. It’s the prime minister of Greenland, Múte Bourup Egede, and he looks furious. “You!” he shouts. “Come with me! We’re going to the police!”

Instead of panicking, I think, This can’t get any more surreal.

President Trump’s bombastic announcement that he intends to annex Greenland to the US has turned the world’s attention on the freezing island located between the Arctic and North Atlantic oceans. Currently an autonomous territory of the Kingdom of Denmark, its strategic location offers an enormous advantage in the increasingly tense dance between three superpowers: Russia, China, and the US. And beyond location, Greenland’s supposed geological riches have also sparked Trump’s interest — hence my 2,000 mile pilgrimage from Toms River, New Jersey, to Nuuk, Greenland, braving the arctic temperatures to hear what the locals actually think about this contentious issue.

Of course, I wanted a statement from the prime minister, and when my emails went unanswered, I decided to do the simplest thing and knock on his door. There was no security, and the young woman who answers the door says the prime minister isn’t home and declines to comment.

I obediently leave, though not before snapping a few pictures of the house, and am only about ten minutes away on foot when I’m accosted by the prime minister himself.

His bluster isn’t intimidating; in fact, I feel bad for him. He appears to be a kind and goodhearted person, but — like many of his citizens —he’s rattled. The sudden world attention to his chilly corner of the planet is overwhelming.

I deflect Egede’s attempts to detain me, and calmly reply that I would not be getting into his car and not going to the police because I hadn’t broken any laws.

He calms down pretty soon and we have a pleasant conversation, though he expresses his frustration at the world’s perspective of Greenland as a Monopoly piece of real estate up for grabs. “We just want to be respected,” he tells me. “We are Greenlanders. We are not Americans. We are not Danes. We are masters of our own fate.”

The few days I spend in Nuuk polling the locals about Trump’s plan pretty much bear out the prime minister’s sentiments. Most are opposed, with only a small mority interested in American citizenship. Mostly though, the plan, which leaves no room for Greenlanders’ opinion, is an insult to their deeply honed nationalistic pride.

But caught in a geopolitical vise and battling a force of nature like President Trump, they may find their feelings don’t matter all that much.

Pulse of the Arctic

I met my first Greenlander in Iceland, a standard stopover for anyone wishing to reach the arctic island. Waiting on line to board the tiny propeller plane for the two-hour flight that will take us across the frozen wasteland, I asked everyone where they were from. Only one traveler was Greenlandic, an elderly woman who lived in Ittoqqortoormiit, Greenland’s smallest town (there are even smaller “settlements.”) Set in northeastern Greenland, the town has a population of 363 people. They survive by hunting polar bear, seal, walrus, and musk ox, and fishing for narwhal. The sun sets in November and doesn’t rise until April. “We get used to it,” she says philosophically.

As our turboprop lands, I get my first view of Nuuk. It’s barely three miles across, clinging to the tip of a finger of land on Greenland’s giant, jagged coastline, like a Band-Aid on the toe of a giant.

Most of Nuuk straddles the shore. The city is built on mountains overlooking twisting and winding fjords. Streets are cut into the sides of the mountains, with the trademark Greenlandic brightly colored homes perched either on top of the ridge lines, or cut into the side. My room was accessed by a rickety, third-floor outdoor landing. I had to climb three stories of snowy, ice-coated stairs to get to the door. Across the room, the mountain angled steeply upward from just below the window.

The harbor is a length of shoreline with ship-loading cranes and docking equipment. Several ships were in port. A large container ship bobbed in the frigid waters. Several ferry boats, used to transport Greenlanders to other coastal cities in the country, were tied near tour boats and a navy frigate flying the Swedish flag. The entire harbor was choked with slush and ice.

Greenland straddles key access routes for commercial and military ships. Russian and Chinese navy assets can only reach the Atlantic by passing through a narrow choke point between Greenland and the United Kingdom, with Iceland in the middle, often called the GIUK gap. Russia has been increasing its Arctic naval presence significantly over the past several years.

Greenland also borders a strategic commercial shipping route, called the North Atlantic Passage, from the northern Pacific to the Atlantic. Ships call at the port often. During the summer, it’s an increasingly popular destination for cruise ships. China has expressed interest in building the “polar silk road” of shipping for its assets, and Russian military bases have sprung up all along Greenland’s arctic shoreline — some as close as within 600 miles.

Whoever controls Greenland controls key access to these strategic locations — hence, Donald Trump wants in.

Unwarranted Optimism

I spend most of my first day meeting people, getting a feel for the locals and their opinions on President Trump’s professed intentions to acquire Greenland as a US territory. About 85 percent say they have no interest in becoming a citizen of the United States.

A day before my departure, I heard an interview with Senator Ted Cruz. “Being an American is the greatest gift you can give a person.” Mr. Cruz said. “I’m sure that when Greenlanders realize, ‘Wait a minute, I can be an American?’ they will jump at the chance.”

His optimism seems to be misplaced.

In the country’s current status as part of the Kingdom of Denmark, Greenlanders are Danish citizens. They enjoy completely free healthcare in Greenland and Denmark, and get paid to go to university. They are part of the European Union and can travel freely and enjoy benefits in all Eurozone countries.

“Why would we want to give that up?” a Greenlander who is already an American citizen asks me. “To be an American, and have to pay a king’s ransom for healthcare that doesn’t work? The US has one of the highest infant mortality rates of any developed country. It’s embarrassing.”

On my first night in Nuuk, I wait for someone I’m supposed to meet outdoors, at the end of a road in a corner of the little city. After an hour of standing at the foot of a towering mountain that was mercilessly funneling arctic winds down my back, I realize I had the date wrong.

Half frozen, I get into a taxi, no specific destination in mind, and ask the driver to take me to a popular social venue. “I know just the place,” the driver says pleasantly, and speeds off into the night, toward what he calls the “most crowded joint in town.”

We pull up in front of a low wooden building, with a saloon-style veranda blanketed in snow and ice. Spiky icicles extend from the roof, and snow drifts many feet high are piled to the sides and cover some of the steps, but warm light spills out of the windows onto the pale street. The place looks comfortable, huddled against the elements, remarkably like the kretchmeh from the stories of my childhood.

When I push open the door of the tavern, I find four men inside, chatting in Kalaallisut, the Greenlandic vernacular. I take a seat and order a Pepsi Max (Coke Zero hasn’t migrated this far north).

The man sitting nearest to me is brooding into his Carlsberg, four empties lined up. I strike up a conversation and find out that he’s 35, and works as a carpenter and construction worker. Native Greenlander. He soon asks me where I’m from.

“America.”

“Trump?”

“Yes.”

The fellow’s demeanor changes suddenly. “So you want to buy me!” he growls. He gets up and stalks off. The rest of the pub goes silent.

“Well, I have something to say about that,” comes a voice. I turn and see a gray and grizzled fisherman. His hands, clutching a pint of ale, bespeak years of hard work in rough weather. His clothing and the faint scent of fish tell the same story.

“Listen, my MAGA friend,” he says. “The older fishermen go out on their boat, into the fjord, in any weather,” he says. “Nothing can stop them. They keep doing their job, every day. All they want is to catch fish, feed their family, and come home to a warm bed. They aren’t interested in change.”

One pint gone, he’s just warming up. He motions to Sven, the bartender, to bring two more. He talks about the need for education, a people’s dreams for independence, and fierce nationalistic pride. He does not want to be American, but he does not rule it out. “Try the younger people,” he suggests. “They’re more interested in change.”

I approach the security guard, a young man named Inutsiaq, who is throwing darts at a board. He, too, doesn’t want to be American. He wants to be Greenlandic. He doesn’t mind the Danish rule over Greenland, but he doesn’t love it.

I try a younger set. A group of teenagers has gathered around a pool table in a corner. They’re about sixteen. There are only three high schools in all of Greenland, and from age fifteen or sixteen, most kids leave home and live in dormitories in one of the few cities that have schools. Like most Greenlanders, they’re friendly and polite, sharing easily in fluent English. They’re clearly familiar with American culture — they’re enjoying Western music and one asks my opinion about the upcoming Super Bowl.

Still, they also say they don’t want to be Americans. They aren’t offended or insulted at the idea, but they appreciate the opportunities they have in Europe as Danish citizens and don’t want to trade them for a tighter connection to America.

The construction worker returns and apologizes. He explains that the topic is a sensitive one. Like many locals, he longs to see an independent Greenland, free of Danish rule. But he doesn’t want to belong to the United States, either. “That country is a mess,” he says. “If Americans were here, they would wreck our land.” He wants neither Danish nor American proprietorship, but can propose no alternative — he knows Greenland is simply not strong enough to survive on its own.

Minority Opinion

Not all Greenlanders are opposed to American involvement in their future. Of the fifty or sixty with whom I spoke, a handful have hopes that it can be a way forward.

Kaataq, a cab driver, says he’d welcome American citizenship. Today, most Greenlanders pay 42 percent income tax to the Danish crown, and some pay as much as 51 percent. “What do they do with all of our money?” Kaataq asks me. “We work and work, and they take it all, and give us nothing.” We pull over to the side of the road; there is a tunnel through the mountainside ahead of us, but it’s only one lane wide. We need to wait for opposing traffic to clear the tunnel before we can enter. “Look at this tunnel,” Kaataq says. “Why can’t we have a normal tunnel? Why so small?”

He scoffs at the perks Danish rule offers in the way of free healthcare and schooling. “Doesn’t help me! I stay healthy. I didn’t go to school. I don’t need any of that. How much are taxes in America?”

I tell him that it varies, with an average of about 14 percent. He’s excited. “Wow, fourteen percent! That would be amazing!”

Then there’s Steve, the only native Greenlander I meet bearing an American name. Steve tells me his father was a traditional hunter with a great love for American music and culture. He named his son after his favorite musician.

Steve doesn’t really want to be an American, but he likes the idea of a Trumpian takeover. He despises the Danes. “They don’t like us, and we don’t like them,” he grouses. “Maybe America will be better, who knows?” But it’s hard to judge how typical Steve’s opinion may be. He is one of Greenland’s few ex-cons, and is bitter at the system. He still isn’t allowed to leave the country.

Passing the ice-covered steps of the Inatsisartut, or the Parliament of Greenland, (Nuuk doesn’t bother clearing snow — everyone is wearing ice spikes, anyway), I meet Hans Enoksen, prime minister of Greenland from 2002 to 2009, and current member of parliament. He’s a big fan of President Trump. Unfortunately, he speaks no English or Danish; only Kalaallisut. He communicates his opinion by saying, “Trump, Trump!” and flashing a thumbs up and big smile.

Some Greenlanders aren’t as emphatic about their opposition as the men in the tavern, but they’re scared.

In a tourist agency office, I meet four people sitting behind desks, working on computers. All express pride in their Greenlander identity. When I bring up the topic of American annexation, they look at each other, hesitant to speak.

Eventually, one answers cautiously. “We don’t want that,” she says. “Look at the Inuit in Alaska, and the Native Americans who lost their land and were confined to reservations throughout your country. We don’t want to be treated the way Americans treat their indigenous peoples.”

The other employees nod in agreement. One adds, “What kind of relationship would we have with the US? With only 57,000 people, we’re too small to be a state. They wouldn’t give us two senators. We would be a territory, like Puerto Rico, Guam, or Samoa. Those places aren’t exactly paradise. We don’t want to look like them.”

Another taxi driver tells me he’s concerned about war. “If Trump wants to take this place, maybe there will be war,” he says. “Who knows what will happen? And if Russia and China get involved? We don’t want this. We just want to be left alone.”

Culture Wars

The morning following my interviews at the tavern, I set out for my next appointment. It’s 10 a.m. but the streets are still dark. I have an appointment to meet with Juaaka Lyberth, songwriter, singer, actor, author, and the closest thing to a Greenlandic celebrity. (Until 1979, Greenlanders were forced to have Danish names, which is why anyone over 50 has a Nordic name.)

Lyberth serves on the Nuuk city council and is active in developing grants from foreign countries to bring Greenlandic art and stories abroad. He’s constantly traveling around Europe, holding cultural festivals and similar events.

He’s waiting for me at the door when I arrive. Like all Greenlanders I’ve encountered, Juaaka offers me tea, coffee, or hot chocolate, which of course, I decline.

His passion for Greenlandic culture is not academic. In his work, he sees the survival of his people, defense of his land, and nationhood against a world that would either devour it or knock it clumsily off the map.

“Greenlandic people have stories to tell,” he says. “We are here to tell them, to make sure the world listens and understands.” Lyberth is at the apex of one aspect of the struggle that characterizes Greenland, that of national tradition and culture versus Europeanism.

Around 70 percent of people living in Greenland are native, descended from the Inuit (the term preferred over “Eskimo,” which is considered offensive). Believed to be originally of Mongol descent, the Inuit were nomadic hunters and fishers that centuries ago spread across northern Canada and into Greenland, where they met Norsemen moving west. They soon dominated the land, and the Norsemen disappeared. Greenland has almost no trees and little farmable land. Its 840,000 square miles are mostly covered with ice. The Inuit survived by hunting the creatures that still live on the island today — polar bear, musk ox, seal, walrus, and reindeer. They fished whales and narwhal.

Today’s Greenlanders are a fully modern people, and the need to purchase the thousands of consumer goods that make up modern life makes the island heavily dependent on imports and trade — mostly with Denmark and other Nordic countries. Paradoxically, they are also fiercely nationalistic. They have a strong patriotic identity and have no interest in being part of any other country. Inevitably, this friction has led Greenlanders to chafe under its subservience to Danish rule for over 300 years.

Uneven Growth

The internal conversation within Greenland around political independence brings up strong feelings. Some of the country’s seven political parties are pushing harder for independence, sooner and faster. Others, although likewise longing for freedom, advise caution.

Juaaka sketches the issues as he talks. Greenland has a national budget of about $2 billion. It currently receives $511 million from Denmark, which it would have to come up with on its own if it were independent. Where would that money come from?

He jots some more numbers, circles them, and draws more lines. In order for the budget to make up for the loss of Danish subsidy, the Greenland Gross Domestic Product has to increase by about 75 percent. How can that increased productivity come about?

There are ways to grow the economy, he explains. Fishing and hunting, the country’s prime businesses today, cannot be expanded, but tourism can be increased and the rich mineral deposits in the country can be mined. But there needs to be diversification. Mines can close suddenly when demand for a mineral drops or the mine empties, and tourism isn’t a stable income. Most importantly, there aren’t enough people in the country for the manpower needed to fill these posts.

“We can’t grow the economy without more workers,” Lyberth explains. “Even now, there aren’t enough people to fill all the jobs that a basic society needs.” For example, there is no defense force. To solve the labor shortage, the government has brought in hundreds of workers from Thailand and the Philippines. But locals are already complaining about the foreigners, while still more are needed.

The population is growing, slowly. The government says there are 131 more people in Greenland this year than one year ago. Nuuk is almost at 20,000 people, and hopes to have 30,000 by 2030. Two airports were just expanded to serve airliners and international travel, and United Airlines plans to launch a direct flight from New York.

But a modern country needs thousands of types of professionals and professional services to function. Greenlanders know they aren’t there yet. When will they be ready? They’ve been grappling with the questions of identity and independence long before US president Donald Trump expressed interest in acquiring the country.

Unconvincing Sales Pitch

US interest in purchasing Greenland hinges on three features: its location for missile defense, its proximity to key shipping lanes, and its abundance of rare minerals. But locals don’t buy it. Most Greenlanders don’t believe that America needs to take over their land for strategic defense, nor does it need to do so to exploit and protect the mines. While they don’t deny the importance of either goal, they say both can be effectively accomplished under the status quo.

Paul Cohen, an American citizen living in Greenland for the last 26 years (and its only Jewish inhabitant; see sidebar), points out that the US military has previously had dozens of bases in Greenland. “And it could have as many as it wants, with a simple phone call,” he says.

Similarly, under Danish law, anybody can come to Greenland and dig for whatever he wants — all that’s needed is a permit, which isn’t hard to get. “There’s no reason for Mr. Trump to take us over to find his minerals,” a ferry operator living Ilulissat, 350 miles north of Nuuk, says. “They can come look now and see what they can find!”

However, it may not be that simple. Energy Transition Minerals, an Australian mining company, did set up an operation called the Kvanefjeld Project, just minutes from Paul Cohen’s home in Narsaq. There are large deposits of rare earth minerals there, formed when an underground volcano boiled near the surface but never managed to burst through and erupt. As it slowly cooled, it formed these deposits, he explains. The company found the minerals it sought, but the ore was tangled and laced with uranium. Copenhagen frowns on mining uranium, part of its antinuclear proliferation strategy.

The locals from Narsaq also put up a fight. Mining the ore would produce tons of radioactive nuclear waste. The company planned to dispose of it by damming a river just upstream from the town and depositing the waste in the bottom of the lake that would form. It would be an environmental travesty, and locals are concerned; what would happen when the dam breaks? The usually calm Greenlanders formed an NGO called Urani Naamik (Uranium? No Thanks), protesting the company’s activities.

In line with their Inuit heritage, Greenlanders are fiercely protective of their environment, inhospitable as it may be. The air in Nuuk is pristinely crisp and clear. Over 75 percent of the power supply to the city comes from a hydroelectric power plant downstream. There is a frozen lake in the mountains above the city, from under which an aqueduct channels water to form the city’s water supply — crystal-clear fresh mountain rain and snowmelt.

Taking control of Greenland might indeed ease the way for mining companies to circumvent environmental issues. But for Greenlanders, that is all the more reason to oppose the move.

“Besides,” Paul Cohen observes, “mines were supposed to be our ticket to independence. Why would we give those up, taking a step backward?”

“What about Russia and China?” I ask. “Might they make a move to capture Greenland for its strategic location and minerals?”

Paul points out that Greenland is a part of Denmark, which is a NATO member. “If anything happens, the US is bound to come to our defense. We stand to gain nothing by belonging to America.” Although President Trump has expressed his displeasure with NATO, it’s hard to believe he would pull out of the treaty just so that he can make US defense of Greenland a bargaining chip.

He also points out that China’s attempts to exert influence on Greenland have been unsuccessful. In the last ten years, China has worked on developing international dependencies among third-world nations. It has given money to and built infrastructure for small countries in Africa, and in exchange, it was given permission to build a port on the Atlantic coast of Africa, causing great consternation in the US defense establishment.

With Greenland facing an urgent need to build more facilities for tourism and air travel, a Chinese state-backed company offered to expand and build international airports at two existing small flight terminals. This would have given the Chinese some leverage in Greenland.

But one phone call from Washington to Copenhagen blocked China’s plans. “Again, the US and Denmark are allies,” Paul says. “There is nothing the president needs that he can’t have already.”

Imperialistic Ideas

If the US can technically protect its interests without actually annexing Greenland, what’s driving President Trump to want to formally take over? Lyberth and Cohen, among others, see it as modern-day imperialism. “Frankly, it’s shocking that in the modern era, we are seeing this kind of expansionist, territorial attitude,” they say. “It’s nothing more than a desire to build an empire and make a stamp on history.” The sentiment is common among Greenlanders, but not universal.

I wonder aloud if there’s anything the US could offer the Greenlanders that would make US control a benefit for them? For example, the administration has promised that it would develop the infrastructure in Greenland, as currently there are no roads between cities.

Greenlanders scoff at this. “It’s impossible to build roads. Suggesting that is like saying they will build us a bridge to Canada. They would have to blast through 500 miles of rock to build one road, and then maintain it and plow it. And then people would still have to drive 500 miles to use it. All this, just to connect a few thousand people?”

President Trump himself hasn’t yet defined his ultimate vision for the US-Greenland relationship. But his man on the ice in Greenland, former Commissioner of the U.S. Arctic Research Commission Tom Dans, has. “It’s time for a U.S.-Greenland Free Association Agreement,” Dans wrote in a report issued earlier this year.

Signing such an agreement would allow Washington exclusive military access to territory and critically, the right to deny access to other powers. In return, the “freely associated” party would receive substantial economic development assistance and investment from the United States. Greenlanders would be able to reside and work in the United States and be eligible for federal programs and services.

What Greenlanders really want though, is independence, respect, and dignity. Independence means a stronger economy, more people, and a bigger workforce. Perhaps, if there was a way the United States could promise those things, employ language that respects their right and ability to self-govern, and devise a roadmap to independence, Greenlanders would be interested.

Caught in a geopolitical storm between a covetous, expansionist US president and the looming threat of Russia and China, one can’t help but feel bad for the Greenlanders. The US alone spends more on defense than Greenland’s total gross domestic product for 400 years. They will likely find that their noble ideas about dignity and independence don’t carry much weight when three superpowers have developed a sudden interest in their vast, windswept land.

But that doesn’t stop them from expressing their views about Trump and his imperialistic notions. When I ask one last Greenlander for his opinion about Trump buying Greenland, he looks at me with pity. “Buy it from whom?” he asks. “Who owns it? No one owns the country. No one owns the land. No one owns Greenland. Not the Danes, not the Greenlanders, and not the Americans.”

LATE ADOLESCENCE

F

or the past 300 years, Greenland has struggled to find its identity as a nation while seeking a pathway toward independence.

The early colonial years were oppressive, with the Danes treating the Inuit as second-class citizens, limiting their rights, and cannibalizing their products, trade, and labor. Until 1979, Danes forced Greenlanders to speak Danish and have Danish names. They took a paternalistic approach to Greenlanders, monopolizing all trade with the outside world under a state-run company called KGH. They went to lengths to block communication and global influences from reaching the locals. Even today, Denmark blocks foreign aid to the island and limits its trade options. The vast majority of Greenland’s exports, such as its robust halibut product, go to Denmark.

When the Nazis occupied Denmark in 1940, some of the control was lost, and locals accessed some American culture. It was an eye-opener for them. Colonization became unfashionable following World War II, and by 1953, the Danes folded under international pressure and ended Greenland’s colonial status, restoring many of their natural rights. The island did not become independent — it became a full-fledged member of the Kingdom of Denmark.

In the 1960s, Denmark launched a program to modernize the country, and sent hundreds of professionals to it. By 1979, Greenland was granted Home Rule, under which a local Government of Greenland was established, with a parliament and prime minister. Still not satisfied, Greenlanders continued to push for independence.

Unlike the struggles for independence of the past, Greenland does not need a military conflict to break free of an oppressive power. Since a 2009 agreement with Denmark, all it takes is a referendum. But Greenlanders are wrestling with the question: Are they ready?

THE MISSILE DEFENSE UMBRELLA

Ahead of my trip, I contacted officials at Pituffik Space Base, the last remaining US installation currently on Greenland, and tried to get clearance to visit. Located 700 miles north of the Arctic Circle and just 900 miles from the North Pole, Pituffik is the northernmost US military base in the world — and with temperatures consistently below 0oF, the coldest. The base, home to the 821st Space Base Group and 12th Space Warning Squadron, is part of the US missile defense umbrella. Greenland lies squarely between the United States and the Russian/Chinese missile threat. Early missile detection at this location is key for engaging and eliminating airborne or ballistic threats before they approach the homeland.

During World War II, Greenland had an important role of ferrying desperately needed aircraft from the US to Britain, combating German U-boat activity, and predicting European weather.

After the war ended, the US and Denmark signed a military treaty, part of which dictated that the US could establish bases pretty much anywhere on the island they wanted — all they had to do was ask. That treaty remains in effect.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1049)

Oops! We could not locate your form.