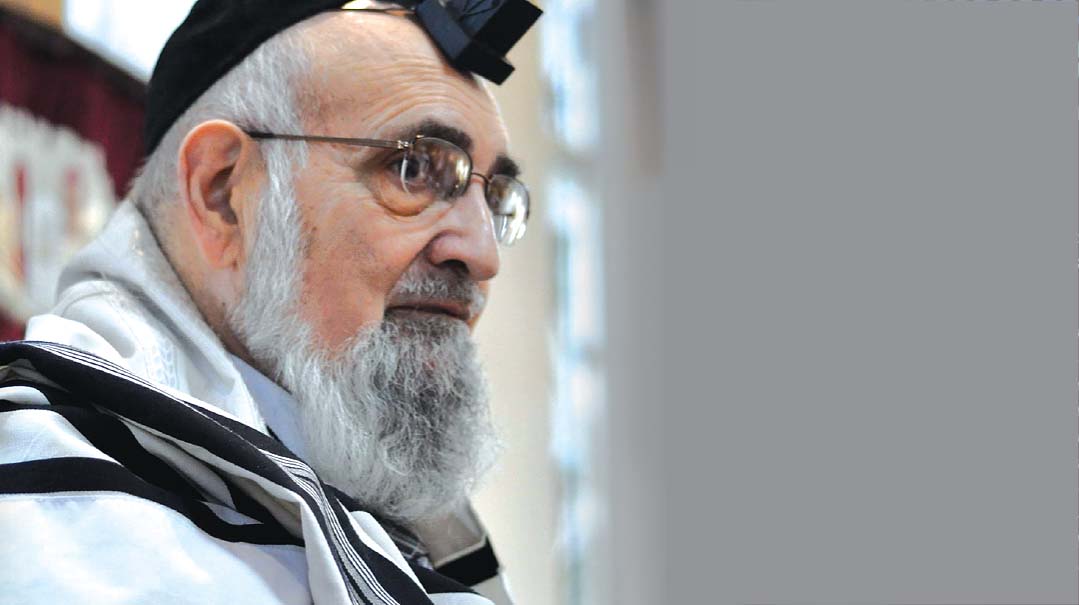

Golden Returns in Silver Spring

| May 11, 2011Rabbi Gedaliah Anemer changed a shul with a thirty-five-man membership and an outside chance of survival into the thriving center that is the pride of Silver Spring, Maryland — with a flourishing yeshivah, yeshivah gedolah, and kollel.

Photos Judah Lifschitz/JFotoArt, Family Archives

As the train clacked farther and farther away from Akron, Ohio, a little boy stared out the window. Nine and a half years old, his only seat in the crammed car was on the lap of the unfamiliar rabbi who had plucked him from his childhood home so he could join his older brother in yeshivah.

Throughout the journey, little Gedaliah Anemer kept reliving his mother’s goodbye at the train station. Years later, he would never forget the vision of his widowed mother from the window as the train pulled out. Although it was tough to raise her three children while keeping her job in the Akron soda factory, it was even harder for her to let him go away to yeshivah.

“It was at that point,” he said, “that I realized how important learning Torah must be, because why else would my mother put herself through such pain?”

Sandwiches under His Bed

Rav Gedaliah Anemer was born in Akron, Ohio, in 1932. At a time when it was rare to find a Jew in middle America who was shomer Shabbos, his father, Reb Zev, turned down an offer to own a Coca-Cola franchise — a deal that would have made him a very wealthy man — because upgrading his own soda factory to a Coca-Cola affiliate would have forced him to work on Shabbos. Tragically, Reb Zev was killed by a drunk driver while delivering a case of soda to a customer, leaving his wife, Rivkah, alone to raise three young children under the age of twelve. At age seven, young Gedaliah’s childhood effectively died, as he recited Kaddish at his father’s funeral. (Many years later in the rabbinate, he found himself in the position of having to comfort other orphans. He would tell them that “becoming a yasom is not a life sentence,” and he would encourage the children that if he could succeed, so could they.)

After the tragedy, Rabbi Shmuel Greineman ztz’’l, the director of Mesivta Tiferes Yerushalayim (MTJ) in New York, visited Akron to fundraise. Whenever Rabbi Greineman would visit a community without a yeshivah, he would volunteer to take any young boys back to New York so they could get a Torah education. As there was no yeshivah near Akron, Rivkah agreed to send her older son, Chaim, to New York. The loneliness was devastating for young Gedaliah, and after Chaim’s continual urging, Rabbi Greineman agreed to take Gedaliah as well on his visit the following year. With a heavy heart but with the knowledge that she was doing the right thing, Rivkah allowed Gedaliah to go, at the age of nine and a half.

Shortly after his arrival in Tiferes Yerushalayim, Rav Anemer came down with tonsillitis. When his mother and younger sister, Mashie, visited him in the hospital, some irate nurses informed Mrs. Anemer that Gedaliah was a difficult patient and was refusing to eat. Ten-year-old Gedaliah explained to his mother that he had eaten only a few pieces of fruit during his stay, because that was the only food he knew was kosher. Pointing under his bed, Gedaliah showed his mother a concealed pile of uneaten sandwiches.

At Tiferes Yerushalayim, Rav Anemer developed a close relationship with Rav Moshe Feinstein ztz’’l. Since the yeshivah did not provide Shabbos meals at the time, Rav Anemer frequently ate at Reb Moshe’s home. Reb Moshe used to give a dollar to any talmid who memorized a blatt Gemara. Young Gedaliah made sure to memorize many blatt Gemara and saved up the money so he could buy a train ticket to go home and visit his mother.

A Pivotal Moment in Washington

Rav Anemer and his brother transferred to the newly opened Telshe yeshivah in Cleveland in 1944, since it was closer to home. (Chaim a”h was killed with his two sons in a car accident in 1961.) At a young age, Rav Gedaliah had already become a talmid muvhak of Rav Elya Meir Bloch ztz”l.

“He was one of my closest friends,” Rav Avraham Chaim Levin, currently Telshe rosh yeshivah in Chicago told Mishpacha. “We had a chaburah together. Although he was such a strong baal kishron, he was still a normal, well-rounded boy. He had strength of character, even when he was young. It takes gevurah to say to your friends who are going off to baseball games, ‘No, that’s not for a yeshivah bochur.’

“After the 24,000 talmidim of Rabi Akiva died, he started over and found five talmidim to whom he would pass on his Torah,” continues Rav Levin. “Our roshei yeshivah lost everything in Europe. All their kochos were focused on us few talmidim. Rav Bloch would emphasize that a person needs to be mekadesh sheim Shamayim in everything he does, and Reb Gedaliah was very much influenced by that. It stayed with him when he went on to build a community; it was evident in every action he took.”

Long after he left Telshe, Rav Anemer maintained a close relationship with Rav Mordechai Gifter ztz”l. After a Telshe dinner at which he was honored, Rav Anemer went to say goodbye to Rav Gifter. At this point, Rav Gifter was suffering from Parkinson’s disease. Rav Gifter asked Rav Anemer, “Reb Gedaliah, you’re the Kohein Gadol of America. Daven for me.” They embraced, both men in tears.

After marrying his rebbetzin, Yocheved Balgley (her father, Rav Balgley, was a talmid of the Chofetz Chaim), in 1954, Rav Anemer, just twenty-three, was selected to head the Boston Rabbinical Seminary, a joint venture of the Lakewood and Telshe yeshivos. A short while later, Rav Anemer decided to interview for the position of rabbi of a shul in Washington DC — a move that would change the face of American Jewry.

Before 1960, there was a sparse Jewish population in Washington, but that changed the year President John F. Kennedy was elected. President Kennedy significantly expanded the size of government and research projects, drawing many Jews to the Washington area. Yet there were pressures to “modernize,” even for those remaining shomrei Shabbos. A small group of Washingtonians belonged to a shul called Shaarei Tefillah, which was was slowly falling prey to these pressures. Wanting to adhere strictly to Torah and tradition, these determined congregants broke off and formed a new shul. They named it Shomrei Emunah.

Rabbi Hersh Mendlowitz, one of the original congregants, remembers the early days of the shul. “When we started Shomrei Emunah, it was a revolution. At the time, people didn’t expect us to survive. I remember when we went to borrow two Sifrei Torah from one of the local rabbanim. He agreed to lend them to us for one year. As he gave them to us, he sighed and said, ‘I hope you last the full twelve months and your shul is still around when it is time to return them to me.’

“When we started out, it was a dark time for Orthodoxy in Washington, let alone the rest of America,” Rabbi Mendlowitz continues. “We had very few people pushing for Yiddishkeit, so that’s why it was so important for us to find a rabbi who could pasken and stimulate the community to grow.”

Sorry, the Position Is Closed

Somehow Rav Gedaliah Anemer — one of the leading lights of Telshe and a self-made scholar — learned of the opening at the tiny Washington shul and decided to apply. At first he was informed that no new applicants were being considered. Rav Anemer called Rav Gifter, who then proceeded to call his close friend, Rav Gedaliah Schorr, rosh yeshivah of Torah Vodaath. Rav Schorr recommended the young scholar to Rabbi Mendlowitz, a committee member who had been his talmid.

Initially, Rabbi Mendlowitz told his rebbi that the application process was closed. “We had already interviewed three candidates whom we felt were appropriate for the position, and we were about to present them to the community. However, Rav Gedaliah Schorr pressured me to interview Rav Anemer, and I’m glad I did.”

Dr. Lee Spetner, another member of the committee, remembers the interview well. “Of all the interviewees, Rav Anemer was the only one without a college degree. Since many of our congregants had PhDs (our shul’s nickname was ‘the Scientists’ Shul’), we initially felt that our rabbi should have one as well. Understandably, we raised the issue, and his response was classic Rav Anemer.

“‘Don’t you think you have enough of those types?’ he replied. ‘There are no lack of PhDs in the shul. In a rav, you don’t need a PhD, you need someone who can pasken sh’eilos, and I could do that for you.’ Far from being shocked at his boldness, the committee was captivated.”

The fatherless boy from Akron who’d won the respect of the Telsher beis medrash found a new position; Rav Anemer became the rabbi of Shomrei Emunah at the age of twenty-five.

The challenges facing the young rabbi were varied and daunting. One of Rav Anemer’s primary challenges was overcoming the fact that he was a young rabbi of a congregation of men who were older, and better educated. Yet members of the Scientists’ Shul remembered how Rav Anemer was able to relate to them on not only a religious level, but on a secular one as well. Although he’d never set foot in a college classroom, he held his own with the intellectual elite.

“It amazed us how he was able to participate in conversations about new scientific discoveries or political nuances,” one member said, “when we all assumed that, as a young religious man who was not actively involved in the secular world, he would be ignorant. And his reach extended beyond the confines of his shul; many community members recall how Rav Anemer treated them with such kindness and respect despite their religious standing; how could they not help but be drawn to him and be influenced to change?”

However, there are times to be gentle and there are times to be firm, and Rav Anemer had the instinct to know which situation called for which response. The community quickly learned that Rav Anemer was fiercely protective of halachah and mesorah, and when he drew a line, there was no force on earth that could bring him to compromise.

Separate in Order to Save

As demographics in Washington changed, members began moving away, and Rav Anemer understood that the future of the kehillah depended on finding a new location. When searching for a new site, Rav Anemer found the land that now encompasses Silver Spring, Maryland. Although it was primarily farmland with sparse housing, he had the keen vision to know that it would be a suitable location to relocate and rebuild his community. And so, a new Jewish community was born.

For a period of time, half of the shul’s congregants still lived in Washington, while half had relocated to Silver Spring. However, until everyone had moved, Rav Anemer would divide his time between the two locations. (Until the construction of the shul’s first building on University Boulevard was completed, Rav Anemer hosted minyanim for Shomrei Emunah in his basement.) He would often spend Friday night in Washington and then walk six miles back to Silver Spring to join his family on Shabbos day. As the shul’s congregation grew, it had to expand from University Boulevard to its current building on Arcola Avenue. Both shuls are still in use.

In Silver Spring, Rav Anemer launched one of his most ambitious projects: a yeshivah high school. Silver Spring had only one Jewish school, the Hebrew Academy, attended by both boys and girls, grades one through nine. As there was no local high school, the only option was public school, or yeshivah high school in Baltimore or New York.

Rav Anemer may have been a realist, but he was not a compromiser, and the state of Jewish education in Silver Spring was far from ideal. Along with a group of dedicated parents, he established a yeshivah high school with separate campuses for boys and girls. Initially, there was some opposition. Many parents felt that their children could just go to public school for grades ten to twelve, and attend an after-school Hebrew program. After all, that’s what they had done, and they felt that they had turned out just fine.

As Rabbi Hillel Klaven, a member of the Rabbinical Council and the long-time rabbi of the Ohev Shalom shul puts it, “They didn’t understand that we needed to separate in order to save.”

In 1964, Rav Anemer established the Yeshiva of Greater Washington’s Girls’ Division, which initially opened with six students, in a shul — determined that the future mothers of Klal Yisrael would be able to pass the mesorah down to their own children. From going door to door speaking to parents, to spending hours upon hours creating the class schedules and grading papers, Rav Anemer had a hand in everything. Today the high school has 190 girls.

Though busy with myriad communal responsibilities, Rav Anemer was always focused on the individual needs of his students. Rabbi Zev Katz, the current menahel of the girls’ high school, remembers one girl who kept coming over to Rav Anemer and asking him questions about Pesach. Realizing that something was probably wrong, Rav Anemer told Rabbi Katz to inquire about the girl’s home situation. They found out that there was no money for regular items, let alone Pesach items. Rav Anemer then gave Rabbi Katz $1,000 of his own money and told him, “Give this money to her and tell her that $750 was to go to the family for Pesach expenses, and $250 was for her own use. I want her to use the money to buy something nice for herself for Yom Tov.”

The following year, Rav Anemer established a boy’s yeshivah high school, a yeshivah that he would personally lead for over forty years. Like the girls’ school, the boys’ yeshivah initially moved from one temporary building to another. In 1968, they couldn’t make the rent. If they did not get $6,000 before the first day of school (an exorbitant amount forty years ago), they would not be able to open. Rav Anemer mentioned the problem to a shul member, who responded that an old elementary school acquaintance of his owned a Korvette’s discount store. They hadn’t spoken in years, but he’d call him, and maybe he’d be willing to donate the money. A few days later, the check came in the mail with a note saying, “I don’t know what compelled me to donate this money, as we haven’t spoken in years, but use it well.” Rav Anemer said that he always took that as a sign that Hashem was on his side.

Rav Aaron Lopiansky, who joined the Yeshiva Gedolah of Greater Washington in 1995 as a rosh yeshivah, described Rav Anemer’s method of teaching. “His shiur was harder than the others, but his talmidim had a kavod and appreciation for him; they didn’t want to let him down. The style of his shiur reflected how he was as a person. He made sure that his talmidim truly understood the concepts they were talking about — one could not give a rote answer.” Many talmidim of Rav Anemer remember how he would often say to a bochur who did not answer with clarity: “If you can’t repeat it over clearly, you don’t understand the concept yet.”

Although he set a clear bar for his talmidim, Rav Anemer did not lose sight of weaker students. Rabbi Dovid Rosenbaum, a talmid of Rav Anemer who eventually succeeded him as rabbi of Shomrei Emunah after his petirah, reminisces. “Rav Anemer had a clear mehalach in chinuch. His goal was to elevate his students. However, he had a caring and understanding for each individual, so if a student was weaker, Rav Anemer would work with him on his level.”

One of Rav Anemer’s original students, Rabbi Yehoshua Wender, remembers his rebbi’s classes. “In the early years, we often had shiur in Rav Anemer’s house, sometimes in the living room, sometimes on the porch. I remember that we were learning Gittin, and we were working on a really complicated Tosafos. The more involved it got, the more excited and enthusiastic Rav Anemer became. He was an inspirational rebbi — the brilliance of that Tosafos, and the brilliance of Rav Anemer’s mind, are what sold me on Torah.”

Rav Lopiansky continues, “I can still see him the first Shavuos night that the beis medrash was filled to capacity. He walked into the beis medrash and on seeing all the tables and shtenders occupied, his eyes filled with tears. I also remember the look on his face one Simchas Torah when a bunch of little boys in yarmulkes raced past him, intent on reaching the Sefer Torah. This was his sign that all his work in building a community of Torah-observant people was bearing fruit, that people’s lives were changing for the better.”

Clean Kashrus

In the early years of Washington and Silver Spring, there were no kosher restaurants or bakeries. While store owners had no objection to selling kosher food, the Jewish community at that time wasn’t large enough to sustain an exclusively kosher enterprise, and hiring a mashgiach was not cost effective. As the population grew, the demand for kosher stores emerged, but there was no kashrus structure in place to accommodate the demand.

Rav Anemer, who straddled his uncompromising principles with an understanding of human nature, was asked to head the Vaad HaKashrus of Washington, a time-consuming position with a commensurate salary. But despite the extra hours this would add to his already overloaded schedule, Rav Anemer refused the extra money, as a guarantee that he would remain impartial; he preferred the extra funds be used to hire a supervisor of the mashgichim.

After Rav Anemer’s petirah, this supervisor shared the following story: “One of the rules that Rav Anemer established early on was that only the mashgiach could have the keys to a business. He would be the one to open up in the morning, shut down after hours, and control the access to the refrigerator.

“At the time, there was one store owner who I suspected of having an illegal copy of the key. I knew they were getting deliveries early one morning, so I drove to the parking lot to see who would open up the store. It was around three in the morning, and when I reached the lot I thought it was deserted. However, I then saw a car in the far corner — it was Rav Anemer. He apparently had the same suspicions that I did, so he decided to check it out for himself.”

“He could put the fear of Heaven into people,” Rabbi Klaven remembers. “If one of the companies or store owners didn’t live up to his elevated standards, Rav Anemer didn’t mince words in letting them know. And he followed through on his word, so if he said that he was going to drop the hashgachah, he did so despite whatever pressure was placed on him.”

And the pressures were many. One of Rav Anemer’s daughters recalls lying awake at night in fear when she was younger, because she overheard one such heated confrontation between her father and a representative of a company whose products were sold in some stores. The man was fighting Rav Anemer’s psak to take away the hashgachah on one of the products if a standard wasn’t met, and he was making threats. But Rav Anemer never yielded.

Rabbi Klaven adds, “When Rav Anemer corrected an owner, it was never personal. I recall a time that a food service owner wasn’t kashering according to Rav Anemer’s stringent standards, despite being instructed to do so many times. Rav Anemer let him know that it was not acceptable, but returned to the store the next day and embraced him — just to show that it wasn’t personal.”

Rabbi Binyamin Sanders, the director of field operations, talked about the policies that Rav Anemer created, many of which are still unmatched under other kashrus authorities. “He insisted that there are mashgichim temidim in every milk and dairy food establishment. Proprietors, even if they are frum, can’t be their own mashgiach. The jobs that a mashgiach can and cannot do are closely monitored and controlled by the Vaad HaKashrus. Rav Anemer wanted to establish that the mashgichim are to be respected, so they are not allowed to do any menial labor such as busing tables and taking orders. Another policy that Rav Anemer created was that caterers from out of state are not allowed to cater in Washington, unless they qualified for a joint hashgachah. We do not supervise products that are out of state.”

We Felt that We Mattered

As rosh yeshivah of the Yeshiva of Greater Washington and av beis din of the Rabbinical Council of Greater Washington, Rav Anemer was universally acknowledged for his mastery of Torah and halachah. Yet he was extremely approachable. Dr. Theo Heller, a congregant who became a close friend of Rav Anemer, noticed how he spoke to children. “When children asked him a sh’eilah, he would meet their eyes, and with a serious look on his face respond, ‘That’s a good question, I’ll look it up.’ It didn’t matter how simple the question was, or that he already knew the answer. Then, he would always remember to call them up on the phone and give them the answer. You should have seen the way the kids’ faces lit up with pride when they got that response — it made them feel important, feel like their questions mattered.”

For Rav Anemer, every community member was like family. A few years back in Silver Spring, a woman in the community needed an emergency bone marrow transplant. Since she didn’t have insurance, she had to come up with $300,000 within twenty-four hours. Rav Anemer made an appeal in the shul, and while it garnered significant response, the required amount was not assembled. However, the next day, the transplant went on as scheduled. It was only after his petirah that the community found out that he mortgaged his own house to secure the money for the operation.

Dr. Jack Calman remembers walking to shul with Rav Anemer on Shabbos mornings, a practice that continued for over ten years. Once Dr. Calman asked, “Rav Anemer, what are you — my rav, rabbi, or rebbi?” Rav Anemer answered, “Your friend.”

The burgeoning Jewish community of Silver Spring, with its hundreds of observant families, thriving schools, and solid infrastructure, might beg to differ. Rav Anemer was far more than a “friend.” He was a force who believed in his community’s potential and used his considerable talents and knowledge to make sure that potential was realized. Though he achieved a name for himself in the yeshivah world, he chose to raise a community in a milieu far removed from the comfortable walls of the Telshe yeshivah.

Rabbi Dovid Hyatt once asked Rav Anemer why he constantly refused offers to speak on the national stage. Rav Anemer answered that he didn’t need those opportunities; he was already fulfilling his mission. “The greatest thing I could say,” he told Rabbi Hyatt, “is that I gave over the mesorah to the next generation the way I received it, unchanged.”

The Final Journey

As Rav Anemer’s life was filled with revealed Providence, so was his end. Rav Anemer was niftar on Thursday morning, Rosh Chodesh Iyar, last year, and his levayah took place a few hours later in his shul. In order to be buried before Shabbos in Eretz Yisrael, there was a narrow window of opportunity to get the aron to Newark. As the hearse left Rav Anemer’s shul, a escort of state troopers surrounded it, intent on ensuring a speedy arrival.

Earlier that week, a volcano in Iceland had erupted and shut down most airspace over Europe. Despite the groundings, the plane carrying Rav Anemer made it to Israel without diversion. It was late Friday afternoon, and the chevra kadisha expected a small, rushed Erev Shabbos burial. Yet as the hearse passed Beit Shemesh, the streets were lined with Rav Anemer’s talmidim standing to honor their rebbi one last time. And at Har HaMenuchos, hundreds of the Rav’s talmidim and community members escorted him on his final journey, dressed in their Shabbos best. The kvurah of the rav who traipsed six miles to serve his community on Shabbos concluded as the Shabbos sirens sounded throughout Yerushalayim.

May he be a meilitz yosher for us all.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 358)

Oops! We could not locate your form.