Giddy Up

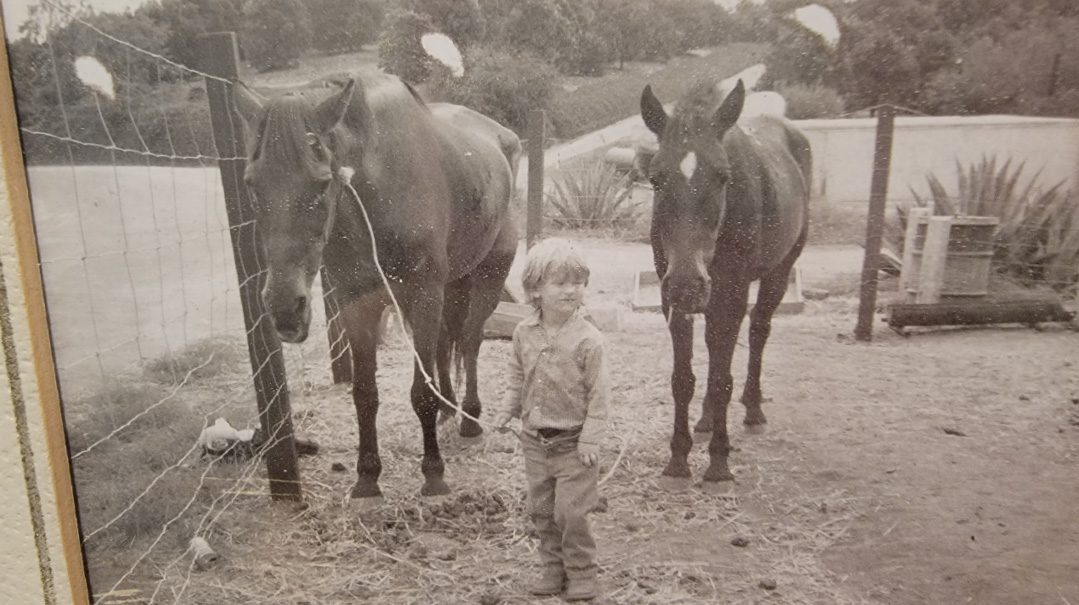

I was three-going-on-four, and I wore cowboy boots, checkered shirts, holsters with two six-shooters, and a ten-gallon hat

Trigger: My rocking horse

Location: An avocado grove in Fallbrook, California

Usually, the first week we visit my mother in Los Angeles, the kids don’t make trouble.

The summer of 2019 was different, though. I’d come from Israel with my younger kids and older grandchildren for a month-long visit, and from the very start, I sensed animated, whispered conferences behind my back. When I accidentally interrupted, the kids, who ranged in age from two to 20, pasted on innocent smiles. By the time I spotted the paint smears on Batya’s skirt and eyebrow, the deed was done.

The six of them grouped together and herded me to the backyard, practically shoving me out the door. I slowly walked into the sunshine, and saw my childhood rocking horse — but it looked different. My old friend shone. Its light brown coat, black mane and tail, brown bit, and red saddle, all looked fresh and clean, and just the sight of my rejuvenated rocking horse took me back to the three years I spent as a cowboy in the 1960s.

I

was three-going-on-four, and I wore cowboy boots, checkered shirts, holsters with two six-shooters, and a ten-gallon hat (probably more like a two-gallon hat; I was pretty small). At first glance you knew what I was: a cowboy. I answered to “Hoss,” the name of my favorite cowboy drama character, the Sheriff of Ponderosa, and I could spell his name long before I could spell “Esther” (although the direction of the “s”s was mostly guesswork).

And I was devoted to my trusty rocking horse. It lived in our backyard, a firm hunk of plastic on heavy springs, not like the thin, cheap plastic you see today. I wasn’t really aware that he was just a toy — in my mind, he was alive, and we played together all the time, the cowboy and her trusty horse.

Being a cowboy suited me. They live lonely lives, and I liked being alone. They are men of few words, and I didn’t like talking. (As the youngest by a long shot, I knew that nobody was too interested in anything I had to say anyhow.) I was so devoted to my alter ego that for nine months a year, I had to change out of my cowboy gear every time I went to nursery school and shul.

“Are you sure cowboys wear dresses?” I’d ask Mom.

“Yep,” she answered, poking her finger into my back as if it were a gun. “Hands up. You’re under a dress.”

But in the summer, when we headed to Fallbrook, California, I could be a cowboy ’round the clock.

Fallbrook is 100 miles south of Los Angeles, 50 miles north of Mexico. Back then, it boasted 6,000 residents spread out over the 22 miles between Old Stage Coach Road and Gopher Canyon.

Cowboy country.

It was primitive. I lived with my two brothers, my sister, and our parents in a 20-foot camping trailer on an avocado grove our father had bought as an investment. Water came from a hose that ran down the hill from the manager’s house, and we got around in a World War II army surplus jeep that came with the grove. For phone service, we had to run up the hill. We made a bonfire almost every night and roasted hot dogs and marshmallows, the others singing cowboy songs around the fire while I tunelessly strummed my miniature guitar.

The trailer had no hot water, but that didn’t keep us from bathing in luxury. We joined the posh country club that served the top brass of a large Marine base nearby so we could shower there. The staff was always horrified to see us all jumping out of an old army jeep with towels and soap in hand, but they couldn’t turn away paying members.

Membership in the club also meant we could use their golf course. Dad tried to teach us, but he soon gave up on me, partly because there were no clubs available for small lefties, and while everyone else golfed, I spent hours on the putting green outside the pro shop. Putting didn’t require any strength or the ability to see far-off targets, of which I had neither, and I was content to spend hours alone trying to whack the ball into a hole.

Despite all of my putting practice, my family decided it was a waste of money for me to go miniature golfing with them. Instead, they left me at the arcade next door (back then there was nothing wrong with leaving a small girl in an arcade frequented by Marines). I’d use up my dimes dueling with the robot cowboy, then wander around watching the soldiers playing pinball and air hockey. One of them gave me a turquoise teddy bear he’d won. It had red tartan arms and legs, and I slept with it, painted pictures of it, and loved it for many years.

We moved out of the trailer quite suddenly the summer I was almost four after a stream of rats rushed out one evening when Mom opened the door.

“We have to get out of here,” she fretted.

My sister ran in to grab Mom’s purse and we went to a hotel for the night, returning the next morning just as the rat catcher arrived.

“You mean to tell me you let some rats chase you out of your trailer?” he drawled with amusement.

My siblings nodded emphatically, so I did, too.

Mom bought two large, square screen tents, and we put them up in the clearing, ten feet from the trailer. The summer I turned four, I sat with Mom in one of the tents, ready to learn to read. Because I was so okay with being alone and I hardly spoke, my family thought I was developmentally delayed, and they hoped a two-year head start might be enough for me to keep up in first grade.

I’ll never forget it: Mom opened The Little White House, a reading primer, and started teaching. I loved it, and I was reading before summer’s end.

MY

summer education consisted of reading and riding (no ’rithmatic), and I picked up horseback riding quickly. We had three horses at our disposal — Rex, Nubbin, and Lucky 7 — and I rode whenever and wherever I wanted.

The horses got minimal attention in the winter, so they were kind of wild at the beginning of summer. The first time we saddled them one summer, Mom couldn’t get Rex to accept the bit. Chet, who helped care for the horses, sauntered up.

“It’s easy to force her mouth open,” he said with a snigger, disdainful of us city folk. “Just push your fingers in here, behind her teeth.”

It wasn’t that easy, though. The horse reared up and my older brother Dovid, fingers deep in the horse’s mouth, went flying in the air. I was too young to realize how dangerous that was, and I laughed hysterically.

When Lucky 7, a black horse with the white blaze on his nose, decided he was done carrying heavy riders, my parents gifted him to me for my fourth birthday. They also gave me a saddle that must have been too small for anyone else. This was the total realization of my dreams: my own horse and saddle! I now completely identified as Hoss, Sheriff of Ponderosa City.

One magical day, we went to the set where my favorite cowboy show was being filmed. The lead actor spotted me in my duds and offered me one of his pistols so we could duel. I had no idea a real gun was so heavy, and I didn’t even manage to wrangle it level to the floor before he shouted “Bang!” and I was (TV) dead.

MY

cowboy career ended rather abruptly. The summer I was seven, I’d said goodbye to Lucky 7 and the other horses, and we drove home to Los Angeles. When we got home, I ran back to the yard to say hello to my rocking horse. I gave him a long drink of water and then set out with him to check on the state of things in Ponderosa. The bank was safe, there were no fights to break up at the saloon, and the Indians had gone. My trusty steed and I were heading off to the prairie to see if all the ranchers were okay when I spotted it out of the corner of my eye: a snake.

I was sure it was a rattler, and I never ran so fast in my life. I slammed the door shut behind me and locked it.

“It was this big,” I told Mom, spreading my arms wide.

“What color was it?” she asked.

“Green.”

“It was just a garden snake. You can go back outside.”

But the Sheriff of Ponderosa was embarrassed at having been so frightened by a garden snake, and I wasn’t sure I believed Mom anyway. And maybe a rocking horse wasn’t as fun now that I had a real horse down in Fallbrook.

The Sheriff of Ponderosa stayed inside for a week, and when I emerged, I was a soldier — Sharpshooter Annie of the 1st Infantry Division, known for my ability to withstand long, solitary stakeouts for the chance at that one perfect shot. I’d traded in my two six-shooters for a long wooden rifle (which can kill snakes without getting too close, should the need arise.) I felt bad about forsaking my rocking horse, but such is the way of life.

These days, my kids know nothing of TV cowboys. They’re hardly aware of TV at all, baruch Hashem. But once they restored my old steed to his former glory, they played with him the whole summer. It warms my heart to see him taking a central role in the summer of another generation. I may have known when I was seven that it was okay to outgrow my rocking horse, but I realize now that I never quite believed it.

Esther Ilana Rabi lives with her family in Jerusalem, where she writes, edits, translates, and teaches composition to undergraduate students.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 969)

Oops! We could not locate your form.