Gartels and Music

How far should composers go to compromise their artistic vision to respond to popular demands and tastes?

For more than half a century, I’ve been involved in the field of Jewish music. My first professional experience came when I was 14 years old and got paid $5 for playing my accordion at a reception for Rav Moshe Feinstein. Since then, I’ve been actively involved in all phases of music as a music teacher, composer, performer, and producer of several albums. Even today, I continue to be a part of the vibrant Jewish music community.

Over the years I’ve thought a great deal about our music. I’ve analyzed it and asked many questions. Are the new melodies being written true Jewish expression, or simply Jewish entertainment? Do we have an obligation to respect long-held musical traditions, or should we break boundaries and enter new, uncharted musical realms? Are musical creations a G-d-given gift, or a structured, carefully crafted melodic product? How far should composers go to compromise their artistic vision to respond to popular demands and tastes?

Quite obviously there are many more thoughts and ideas that have been and should be addressed, but for the moment let this suffice.

Recently I met with a distinguished, well-known, and respected rosh yeshivah — a true mechanech, and a mentor of young men and women. He knew I worked in the field of Jewish music, and so he asked me how we might refocus and reeducate the current generation of young people to be more discerning in their musical tastes. Most specifically he was uncomfortable with the musical sounds and style of dancing he heard and observed when his students participated in simchahs.

I thought about his request for a while, Finally I got back to him with the following idea. After reviewing it, the rosh yeshivah gave it his personal approbation and asked me to find a forum that would bring it to light with the hope of perhaps effecting a change for the better.

There is a prevalent custom among many male Jews to don a gartel — a woven belt or sash around the waist, besides a regular belt — before their daily prayers. There are several reasons brought for this practice, the most basic being to allow a person to discern between the upper part and the lower part of the body. Although, in truth, an individual is one totality, wearing a gartel subtly steers the soul to acknowledge that the human body has both higher, lofty functions, also referred to in chassidus as the nefesh hasichlis, as well as those that are more basic and mundane, which is referred to as the nefesh habehamis. Without much elaboration, it would logically seem that tefillah, prayer, should be associated with the upper part of the body, where there is nobility of thought, higher purpose, and intellectual striving and questing.

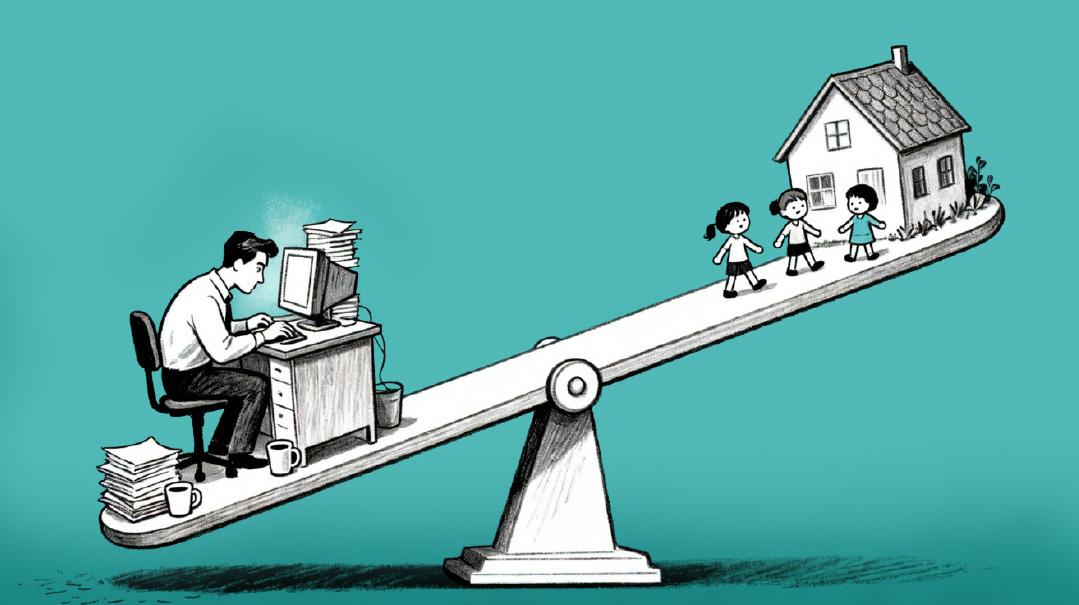

Music, in many ways, has parallel components. There are melodies and cadences that can lift and elevate our minds and souls to indescribable heights. On the other hand, there are melodies and rhythms that can bring us down to non-thinking, primitive states. In truth, there are only seven basic notes in the musical universe. Composers and musical craftsmen arrange and tailor those seven notes, along with their rhythms and lyrics, to engage whichever sphere of their listeners they wish to appeal to. (I do not wish to divide music into good and bad camps; rather, I just want to point out that all music compositions fall somewhere on a continuum, at one end appealing to the lofty, noble parts of human consciousness, and at the other, the more physical, coarse, mundane aspects.)

When one searches out musical experiences, there is obviously an enormous range of what one can choose to listen to. This holds true even when one comes to an event, such as a wedding, a bar mitzvah, even a shopping venue, where music is part of the atmosphere. At all these experiences you can apply the gartel test. Ask yourself the question: Which aspect of my neshamah does this music appeal to? Is it the nefesh hasichlis or the nefesh habehamis? You can, with a bit of tact, even ask your children the same question about their musical choices. Additionally, when there is time and place, you can pose this question to popular performers and band leaders.

This question and its ramifications, I believe, might be well worthwhile to be pondered by the generation of young folks who make up the chasunah crowd (18- to 28-year-olds). This group seems to be the current-day taste-makers and social leaders of modern Jewish music, styles and tastes. Buttonhole one of them and give them the gartel test! Ask them if they want to dance at their friend’s chasunah with music that appeals to the nefesh habehamis or the nefesh hasichlis.

At first blush, I doubt many of them would grasp the subtle distinctions, but… it might begin a conversation, and ultimately, get them thinking about the music of modern Jewish times.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 797)

Oops! We could not locate your form.