Future on a Canvas

| November 2, 2021Pioneering chassidic artist Baruch Nachshon brushed his inner fire onto a worldwide canvas

Photos: Itzik Belinsky, Family archives

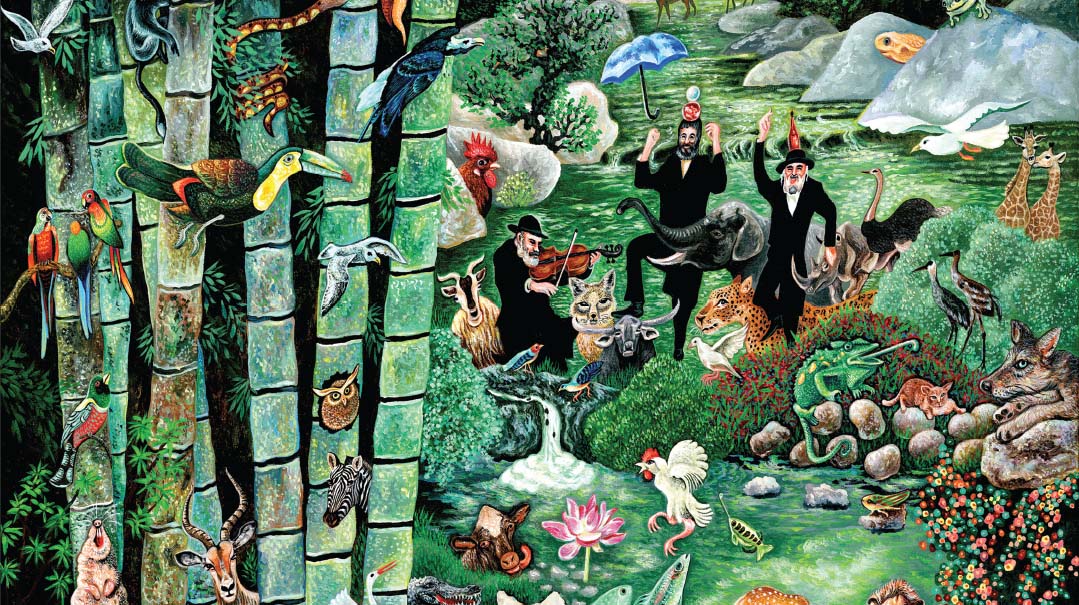

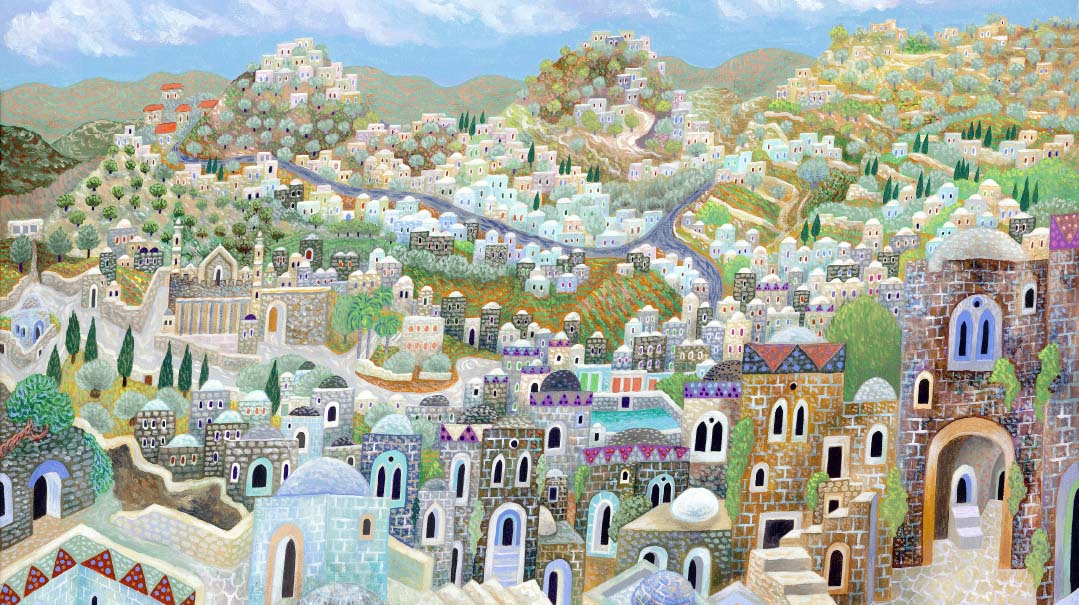

It was one of those visits you never forget, the tone set as soon as I walked through the front door of the Kiryat Arba apartment and stepped into the living room, my senses accosted by a dizzying array of colors and images. At first, it was hard to decide if I’d walked into an art gallery or a shtibel. There were paintings and creations everywhere, filled with kabbalistic symbols and motifs — Chevron landscapes and images of the messianic era, with flowers and domed rooftops and dancing chassidim and flying tefillin — and even an old, red velvet chuppah on the ceiling that had been rescued from an abandoned shul in the Bronx. And then there was the mizrach wall, with an ancient-looking aron kodesh, a bimah and an amud for tefillah. Yet instead of the traditional “Shivisi” sign, there was a canvas with brushstrokes of a blue fire on white, and in the center, the letter Yud; it was hard to tear my eyes away from it.

This was Baruch Nachshon’s art gallery, living room, and on Shabbos, his shul — the sefer Torah safely tucked away behind a velvet curtain. Nachshon, a pioneer of contemporary chassidic art, chassid of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, and, together with his wife Sarah yblch”t, a leading force behind the re-establishment of the ancient Jewish community of Chevron following the Six-Day War, passed away Erev Yom Kippur at age 82. But his spirit lives on in the homes of thousands, their walls still radiating the fire in his nefesh as his canvases fused ancient wisdom with the tangible images of a glorious future.

When we met three years ago, it was on his terms. He entered the room wrapped in a tallis and tefillin, and I remember wondering if he was real, or if he was an apparition who had somehow stepped out of one of the paintings surrounding me. He was slim and tall, with a long beard that had turned white years ago, a pair of piercing eyes that peered through glasses, and topped with his trademark black beret.

He didn’t want to speak with tefillin, so he just proffered five long artists’ fingers and went back to finish davening in his private shul.

As he sat down to eat his organic breakfast, he told me how he’d rarely leave his home, a 15-minute walk from the Mearas Hamachpeilah. “My business is about concentration,” he told me, “so I try to avoid distractions. I don’t go to weddings or participate in events or gatherings. When I go to the city, the frenetic pace disturbs me. The cars speeding on the roads continue speeding in my mind for a long time afterward. Here, in the city of our Avos, I have quiet and focus.”

And then he added thoughtfully, “But you know, sometimes an interview can also be a shlichus.”

The Highest Inspiration

Baruch Nachshon was born in Haifa in 1939 to staunch Mizrachi-oriented parents who had come from Poland before the war. He got his first inspiration from the scenery of his childhood, around the area of Haifa Bay — the clouds, the rain and the Arab neighbors. “Every morning,” he said, “I saw the Arab shepherds climbing the mountains to pasture, and then returning toward evening. I was fascinated by the plants that managed to grow between the boulders, and I loved how the mud changed form with every footstep.”

When I asked him how he had discovered his artistic talent, he quoted himself: “Many years ago, I was invited to deliver a lecture at the Beit Knesset Hanassi in Jerusalem, and the first thing I told them was, ‘I am currently in mourning.’ Everyone looked at me in surprise. I took a moment of silence and told them that my preschool teacher, my ganenet, had passed away that week. She was the first one to see my creative side and encourage it. She’d give me a paper and crayons whenever I made a ruckus in the classroom. And I stayed in contact with her all those years.”

School never interested him. Instead, he’d stare at the white ceiling and imagine it as a large white canvas, where in his mind’s eye he’d paint to his heart’s content.

When Baruch was 11, his father realized that it was time for proper art instruction, and took him to study under artist and photographer Solomon Naroni, a student of French artist Paul Cezanne. Naroni was also the court artist for King Farouk of Egypt.

“I was the only one, beside his wife, who had the privilege of seeing him in action. He never let anyone else into his studio while he painted,” Nachshon said. “Naroni wasn’t mitzvah observant, but when Shabbos came, he put down his brushes. It wasn’t easy because, observant or not, on Shabbos, there is the highest inspiration, and he felt it too.”

Nachshon, who could never tolerate labels or sectorial compartmentalization, admitted that even before he discovered chassidus, “I was always looking for the neshamah, the light.” During his teen years, he learned at Yeshivat Kerem B’Yavneh — and then came 19 Kislev, the “Chag HaGeulah” for Rebbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the first Lubavitcher Rebbe. A few bochurim traveled to the Chabad yeshivah in Lod for the farbrengen, and Baruch joined them.

“I sensed the Jewish soul crying out, and it drew me in.”

Soon afterward, Baruch switched yeshivos and began learning in Kfar Chabad. Then he went to the army, serving in the Nachal division that helped develop new settlements. There he herded flocks of sheep, which spoke to the artistic part of his soul.

After the army, Baruch married Sarah, whose parents were among the founders of Kfar Chassidim. They drained swamps, lived in mud huts, and suffered from malaria. Years later, when the Nachshons joined the founding families of the renewed Jewish community in Chevron, it was a continuation of what her parents had taught her about sacrifice for Eretz Yisrael.

Meanwhile, Baruch had been in correspondence with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, who helped give him direction in his art, and as a newlywed, he wrote to the Rebbe saying they wanted to travel to him. “But the Rebbe said we shouldn’t go into debt,” Nachhson remembered, “so we scrimped and saved for an entire year until we had enough money for third-class passage on a ship to New York.”

You’ll Rectify It

What happened next is a story Nachshon related many times since. In a certain sense, it became the backstory of all his paintings. Two days after he and Sarah landed in America, he had a three-hour audience with the Rebbe — and it was a conversation that changed his life. It began at midnight and lasted until three in the morning. He told the Rebbe everything he had been through, and then the Rebbe told him something that would be the key to his future: “Many generations have passed and the ability to paint in a kosher way wasn’t rectified — you will rectify it.”

From that point on, Reb Baruch told me, that sentence never left his mind. “I repeat it when I walk, when I lie down, when I get up. That’s my life’s mission — to rectify the ability to paint in a kosher way. But when the Rebbe said it back then, it frightened me, and I asked him what he meant ‘in a kosher way.’ The Rebbe instructed me to ask a rav. I asked two rabbanim, one Litvish and one chassidic: Rav Yosef Eliyahu Henkin from the Agudas Harabbanim, and Rav Zalman Dvorkin, the rav of Crown Heights. They gave me guidelines about what was permitted and what wasn’t. I then asked the Rebbe who should guide me. He directed me to a young chassid who was about my age, who took me to a famous artist named Chaim Gross, a Ukranian-born artist best remembered as one of America’s foremost sculptors.”

That’s when his mettle would be tested. New York of the 1960s was at the helm of pushing the boundaries of freedoms, especially manifested in culture and art. “When Gross heard my story,” Nachshon related, “he informed me that he was ready to give me three stipends on the spot, each one of $10,000, for three prestigious courses. When I tried to understand what exactly was taught at those courses, and what the atmosphere was like, I realized that it would be a big problem. That was certainly not the purity the Rebbe had in mind. I rejected the offer, even though I was literally a pauper at the time.”

As Nachshon was about to leave, Gross jeered at his decision and said to him, “The Lubavitcher Rebbe understands halachah, but Chaim Gross understands art.”

“Fifteen years later, the story came full circle,” Nachshon related. “I was in America again, and I presented some of my works to Gross. He was honest enough to admit, ‘The Lubavitcher Rebbe was right. Chaim Gross was wrong.’”

Still, the couple was in New York and destitute. The Lubavitcher Rebbe again came to their aid and gave Baruch a stipend to earn a degree at the School of Visual Arts and money to live on for the entire year. He even told Sarah, “This is not just for food. You can buy yourself a wig as well.” At the years’ end, with no parnassah on the horizon and with the blessing of the Rebbe, the Nachshons returned to Israel and settled in Jerusalem.

Secrets in the Wine

Nineteen sixty-seven was the year that changed many lives in Eretz Yisrael — the young Nachshon family as well. They were living in Jerusalem with four small children, and Baruch was beginning to make a name for himself in the Judaica art world with his Kabbalah-inspired paintings. Yet they wanted something more, and took the miraculous victory of the Six Day War as a sign that Eretz Yisrael in its entirety was beckoning. Before Pesach of 1968, they saw the following sign: “Wanted: Families or singles to resettle ancient city of Hevron. For details, contact Rabbi M. Levinger.”

And so, on Pesach of 1968, they joined Rabbi Moshe Levinger a”h, and several other families and young singles, and planted themselves in Chevron’s Park Hotel. That was the beginning of a three-year-long sojourn in Chevron: Defense Minister Moshe Dayan was anxious to remove the guests from the hotel. He told them to either go back where they came from, or to move to the military compound high on a hill overlooking the city, and six weeks later, the Nachshons and another 30 overjoyed Park Hotel settlers moved into their new home in the Military Compound, which served as a police station as well as an Arab prison.

Each family was allotted one room and they had to go outdoors to reach the bathroom — a military-style lavatory consisting of a hole in the floor, surrounded by a few boards.

While government operatives assumed the families wouldn’t have the wherewithal to stay, they underestimated the Chevron “squatters;” and the entire country celebrated when the Nachshons gave birth to their fifth child, Shneur Chevron, the first Jewish baby boy born in Chevron since the Jewish community was expelled after the massacre in 1929. Still, making a bris in the Mearas Hamachpeilah was illegal, and so the ceremony took place in the Military Compound.

(Making a bris milah in the Mearah was not in itself forbidden — the crime was bringing in wine, which is forbidden by Islam. But two years later, with the birth of the Nachshon’s seventh child (a girl was born in between), Baruch Nachshon decided to have the bris in the Mearah regardless. Without fanfare, a bottle of wine was brought in following the Minchah service, and the ceremony proceeded to its conclusion without a hitch.)

Meanwhile, the Military Compound, where the families lived until the building of neighboring Kiryat Arba in 1971, was bursting at the seams, with a wave of new births adding to the already cramped conditions. One young wife approached Rabbi Levinger in tears: “I don’t mind living in the army’s carpentry workshop, but could they at least move the stack of blocks away from the window so we can have a drop of light?” On another occasion, the harsh environment exacted a more tragic price: Avraham Yitzchak Waldman, the firstborn son of Kiryat Arba Rosh Yeshivah Rabbi Eliezer Waldman, fell into a vat of boiling water while playing and was scalded to death.

At one point, the Nachshons wrote the Lubavitcher Rebbe a long letter in which they outlined the physical challenges, including the difficulties in providing the kind of chassidic education they desired. The Rebbe’s reply was concise — words that kept Baruch and Sarah Nachshon going forward despite the challenges: “Harei batem lagur b’Chevron. Mah hashinuiy? — Here you came to live in Chevron. What has changed?”

After being squashed into the Military Compound for three years, the Nachshons moved to Kiryat Arba, the modern city authorized by the government as a Jewish settlement alongside Chevron. Meanwhile, they had another son, and again decided his bris would be in the Mearas Hamachpeilah, even though the ceremony was still considered illegal. But as they proceeded to recite the brachos, in stormed an officer, who told Baruch he was under arrest, knocked over the cup of wine, and then proceeded to mop it up with Baruch’s yarmulke so the Arabs wouldn’t see it and be offended. An hour later, though, Baruch was released, because the officer had unwittingly spilled out the evidence: the offending cup of wine.

The baby, named Avraham Yedidyah, would in his short life — and death — become a catalyst for renewal. Little Avraham died in his sleep at six months old, and through their pain and shock, they channeled their grief, deciding that the baby who had his bris in the Mearah would be buried in Chevron’s off-limits ancient Jewish cemetery. The military command objected to the burial, and as the funeral procession reached the entrance to Chevron from the Jerusalem hospital where the baby was declared dead, the commanding officer told Sarah, “Mrs. Nachshon, do yourself a favor, turn around and bury your son in Kiryat Arba, where there’s a permit. Who knows if you’ll even have access here in the future?”

Soon there were around 200 officers surrounding the motorcade, with orders not to let the funeral procession advance, but Sarah was undeterred. She got out of the vehicle, took the baby in her arms, and proceeded to walk. When the soldiers saw that she was passing the roadblocks on foot, they were stunned, but a few minutes later, the commanding officer ran up to her and told her she had special permission from the defense minister to bury the child. And that’s how the ancient cemetery was restored to Jewish hands.

Living in Kiryat Arba didn’t stop the dream of returning to the City of the Patriarchs, though. One night in 1979, Rabbanit Miriam Levinger a”h drafted Sarah into an operation that was to radically alter Chevron’s Jewish face. At 4:30 in the morning, together with a dozen women and thirty-five children, they cut through barbed wire, climbed a ladder that was standing on a truck parked behind Beit Hadassah, the Hadassah Hospital building abandoned since the massacre of 1929, and hoisted themselves through the glassless windows. The dirt and rubble were up to their knees, and there was no plumbing or electricity. The first thing they did was to clear out an area where they could find the floor and put down mattresses for the children. The soldiers on duty in front of the building (Beit Hadassah had several times been a target of attempted settlement) discovered the group after sunrise, but by then it was too late: Jewish settlement in Chevron had been renewed.

The army didn’t know what to do with the women. In the end, they were willing prisoners for the first six months, with no one allowed in or out. Eventually, husbands were permitted to join their families for the Friday night meal. For months, the people of Kiryat Arba handed the women food through the window grates. For a bathroom they hung up a blanket around a large garbage can with a hole; every few hours one of the women emptied it into the sewer and disinfected it with bleach. For showers, each person got a bucket of warm water, which they splashed over themselves standing in a baby bathtub.

Today, of course, there are dozens of families and hundreds of yeshivah students living in Chevron proper, in various reclaimed Jewish buildings and in new apartments in the renovated Jewish Quarter.

After a year in Beit Hadassah, however, even as husbands were finally let in and the building was slated for eventual renovation with modern apartments, Sarah realized it was no place for her artist husband, who needed the quiet and serenity of their Kiryat Arba home in order for his talent to flourish.

Under the Bridge

The paintings from those early days in Kiryat Arba had their own style — many of them in black and white. “But then I met an elderly Breslover chassid, who instructed me to say all of Sefer Tehillim every night for 40 nights straight, beginning at chatzos,” Reb Baruch told me. “From that point on, I was blessed with abundant inspiration, which I translated into forms and colors.”

His success transcended borders and communities. He visited locations around the globe, and held exhibitions in cities all over North and South America. “I’m the shaliach of the paintbrush,” he told me. “My job is to convey the message in the medium.”

He pointed to a reproduction, the original of which, he explained, was hanging in a Japanese university, in the office of a professor of meditation.

When I asked him what he thought the secret of his creations was, he repeated the story of the treasure under the bridge. “You know, the first time I visited the Guggenheim Museum of Modern Art, I wandered through the building — a huge impressive structure built like a huge helix with massive paintings hanging on all sides, each one the size of an entire wall. You look, and you don’t quite understand what it is exactly that you’re seeing. It’s a mixture of colors that can pique your curiosity, but not your emotion. I went in empty, and left even emptier.

“It made me think of the chassidic story about a Jew who dreamed that under the bridge in Prague was a huge treasure. He made the effort to reach Prague, and under the bridge he met a soldier, who told him that he dreamed that there was a treasure under the oven of that same Jew. That’s the story of the Jews and art.

“Today there is tremendous searching and thirst. You see so many Israeli artists today looking for the treasure. They copy and imitate art from all over the world. But it’s all one big emptiness. The real treasure is within our own souls, if we’re courageous enough to dig deep and find it.”

In 1979, while Sarah Nachshon was holding her family together in Beit Hadassah, Baruch Nachshon traveled to New York to exhibit his work and had an audience with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, who suggested that he exhibit his work at Chabad-Lubavitch World Headquarters, and that the Rebbe himself would come to view it — which he did.

At the end of the exhibit, the Rebbe asked the artist, “Did the people buy anything?” When Nachshon responded that the prices for his paintings were too high for most people, the Rebbe suggested that he sell his art worldwide in all forms, including prints and lithographs.

“When one sees something positive in their home, it influences the entire home,” the Rebbe told him.

Find the Light

Behind the dining room that served as Baruch Nachshon’s private shul was his studio, which he called “the lab.” There was no breathtaking scenery — just an antique desk, tubes of paint and some brushes and canvases. He didn’t need stunning views, he told me. His biggest inspirations came from the seforim on the shelves behind him.

On the wall opposite him I noticed Samurai swords, an array of hats, and a huge banner in Chinese calligraphy. “I collect experiences,” he related. Every item in his collection taught him something.

For me, the most fascinating thing was his sketchbook, where he’d sketch his ideas before beginning to work on the canvas. Many of the drawings had a title and some also had longer explanations. For example, on the initial sketch of a drawing called “Light of the Crown,” he wrote, “After learning the sefer Torah Ohr, Ma’amar Lech Lecha.”

One of the techniques he used was something called “pointillism,” where thousands of individual dots are applied to create an image. For example, only after looking closely at the figure of a chassid with his arms raised in tefillah, do you discern that the figure is actually comprised from the words of an entire chapter of Tehillim. “It happened that people purchased paintings from me, and only years later did they look at them and suddenly realize more and more detail,” Nachshon said. “The truth is that I don’t always know all these details either — that’s just how it comes out for me. But that’s really how it is with any gift from Above. A person has a special mission to carry it out, or he wouldn’t have received it.”

Nachshon said that if he was once a perfectionist, he long ago let all that go. And his message was more than just about canvas and a paintbrush. “Even if something goes wrong, you can always fix it and turn it into a creation of light.”

—Rachel Ginsberg contributed to this report

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 884)

Oops! We could not locate your form.