Full Circle

At a Conference of European Rabbis summit, war and refugees are once more on the agenda

Photo: Eli Itkin

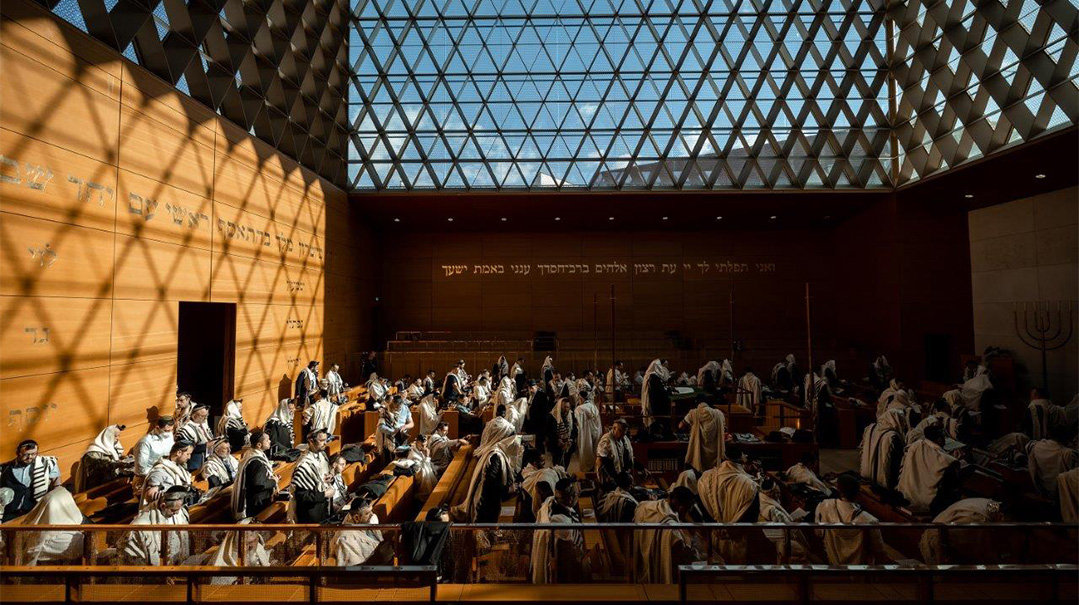

1. Center of Gravity

Like many European cities caught in the wave of pro-Kiev sentiment, Munich’s municipal buildings, including the theater and local museum, fly Ukraine’s blue and yellow flag.

Like most media outlets across the West, Munich’s main newspaper — the Süddeutsche Zeitung — prints updates on the Donbas on the front page.

At the Grand Westin Hotel, which played host to the Conference of European Rabbis (CER) convention that took place in the city last week, Dmytro — who’d worked in the hospitality industry in Kiev — managed the front desk in fluent English and talked of building a new life.

This city — the cradle of Nazism — tells a German and wider European story: war, refugees, and geopolitics are creating fresh wounds, in a continent where the scar tissue of the last conflagration is barely healed.

As an organization whose center of gravity shifted eastward when Jewish life flooded back into Eastern Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall — in Munich’s government-sponsored shul (above) Russian-language siddurim dominate — the CER reflects those wider forces at play on the continent.

Photo: APIMAGES

2. Poor Prospects

Enormous sums — likely north of $100 million — have gone toward rescuing Ukrainian Jews in the last three months in campaigns that many of us have contributed to. But in many ways, the plight of the far larger Russian Jewish community has been ignored.

Three sanctioned oligarchs — Roman Abramovich, Mikhail Fridman, and Moshe Kantor — used to pump tens of millions of dollars annually into the Chabad network in Russia, paying the salaries of rabbis, funding community centers, and feeding poor and elderly Jews.

That whole system is now under pressure as the Western assets of the oligarchs are frozen.

“Both Ukrainian and Russian Jewish communities face a smaller, more impoverished future,” says CER president and Moscow Chief Rabbi Pinchas Goldschmidt, who’s now barred from Russia for speaking out against the war.

For those with the skills and assets to leave, the Gulf — where thousands of Russians have pitched up — is an attractive destination. But with the West closed, for most the only possible destination is Israel.

Photo: APIMAGES

3. Poles Apart

What of the Jewish refugees themselves? New York–born, YU-educated Rabbi Michael Schudrich has been Poland’s chief rabbi since 1990, and since Putin’s invasion, he’s had to see to large numbers of refugees who headed to Poland, which is both Ukraine’s most developed neighbor and the one with which it shares the longest western border.

There are currently about 500 Jewish refugees under his care, including those who have a friend or relative in Western countries such as Germany or Switzerland, and those who are intending to stay in Poland.

“Aid agencies anticipated flows of hundreds of thousands, not millions of people,” he says. “We had to deal with a thousand people for the Sedorim. But as things settle down and interest in them wains, getting the refugees remote work like in IT companies is now our priority, because the government provides free health care, but the rest is on us.

“The whole Jewish aid infrastructure for Eastern Europe has had to be rebuilt, but our challenge is to scale up while not losing the focus on individuals.”

Photo: APIMAGES

4. Business as Usual

The CER is a high-level rabbinic-political confab, reliably drawing senior figures from both worlds wherever it meets. On the sidelines, I talked with Armin Laschet, who was previously head of North-Rhine Westphalia, a German state, as well as a candidate for chancellor in the national elections held last year as head of the CDU, Angela Merkel’s former party. A prominent voice on foreign policy, Laschet is a critic of BDS as well as the softness of German policy toward Vladimir Putin — yet his own words indicate why Germany can’t stand up to Russia.

Asked why Berlin had not made good on its promises to transfer major weapons systems to Ukraine, he told me that Putin should be made to lose — a declaration that Chancellor Olaf Scholz has refused to make — but that this could mean many things. “Do we want him to go back to the 2014 lines, to the positions at the beginning of this war?”

In other words, Germany’s vaunted foreign-policy shift may yet happen, but even among relative hawks, there’s more appetite for reducing dependency on Russian oil than for arming Russia’s foes.

5. Dark Shadow

Twenty minutes outside Munich, in the Dachau death camp, Germany’s post-Holocaust pacifism — and paralysis — come into view.

Hundreds of people, from school age to old-age, walk slowly around the remains of the first outpost in Hitler’s kingdom of death.

Having split off from the larger CER group, I’m the only visibly Jewish figure around. As I walk past groups listening to talks about “Juden,” the crowds visibly part as people notice me. I feel like Exhibit A in the museum. Standing looking at the Appelplatz, I feel a sense of privacy violated — this is my first encounter with a death camp, and part of me wants to mourn alone.

Once, a German teen walks up to me, and as a mark of respect, wishes me “Shalom.” This, then, is the product of an education system where Holocaust studies are obligatory.

One of the wealthiest, most advanced countries in the world, Germany could re-arm and do far more to protect Europe. As Putin advances and the US retreats, and with Britain and France not powerful enough to take America’s place, that’s now a strategic imperative.

Whether Germany will learn to do so while the last survivors are still with us is an open question.

Photo: Eli Itkin

6. Evil Next Door

Down the road from Dachau is the town of 46,000 that gave the death camp its name. Along one of the main roads is a lumber yard, whose sign proclaims with no hint of irony that the business is the “number one supplier of wood in Dachau.” It’s hard to imagine why a place whose name is so redolent of evil hasn’t been renamed.

But the utter domesticity of the setting is symbolic both of the Holocaust and the nature of evil.

In the city where Nazism was born, where Adolf Hitler’s failed Beer Hall Putsch took place and where stormtroopers first strutted, there’s not much to see. Hitler’s apartment is still there (it’s a police station today), but the fiendishness has no expression. Instead, back gardens give way to a death camp.

In the juxtaposition of mundaneness and monstrosity, there’s a deep lesson that Germany — and others who proclaim “Never Again” — would do well to remember.

Evil of the worst kind is never far away; it’s not some monstrous, extraordinary apparition, but the terrible actions of perfectly ordinary people who can go home from a day of mass killing to tend the roses.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 914)

Oops! We could not locate your form.