Frontline Warriors

| February 28, 2023One year into a bitter war, Ukraine’s shluchim remain staunchly at their posts

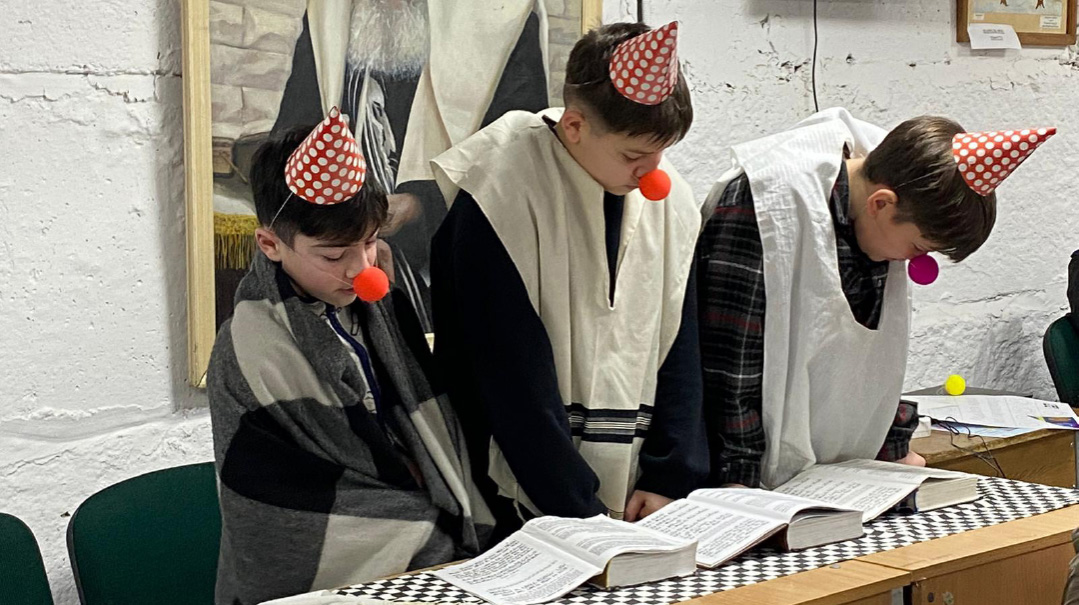

Photos: Kharkov Jewish Community

The winter has been freezing and dark, the cities have been turned into bombed-out casualties of war, and the fear and uncertainty have taken a huge psychological toll. But that hasn’t stopped the community rabbis and rebbetzins of Ukraine, who’ve refused to jump ship as long as they’re needed by the remaining members of the kehillos they toiled for decades to build

IT’S

been a year since Russia’s headline-grabbing invasion of its smaller neighbor, but while the world anticipated a quick fall for Kyiv, the battle still rages on. The media has given extensive coverage to beleaguered Ukraine’s defense, but there are other frontline soldiers too, out of the limelight, equally intent on giving the battle their all.

All across the Ukraine, Chabad shluchim have voluntarily returned to the war zone, to help fellow Jews. Having fled along with millions of others when Russian victory looked certain, the decision to return meant enduring months of austerity conditions in a country under constant aerial attack.

In the process, the families who made their way back to Ukraine were implementing a basic Chabad philosophy that shuns political affiliation and speaking out on the broader issues of the day in favor of community building.

In an interview with Mishpacha last year, chief rabbi of Russia Rabbi Berel Lazar — whose pre-war remit included bringing many of these same families to Ukraine —set out the principles that have enabled Chabad to cultivate working relationships with governments worldwide.

“Your job is to teach the Jews about Yiddishkeit and to help them materially and spiritually,” he told shluchim as the war destroyed old certainties about their jobs. “Anyone who demands that you get involved in the war situation is trying to get you to miss the mark. That’s not your job.”

The balance of material and spiritual that Rabbi Lazar referred to has changed under the deteriorating conditions of wartime Ukraine. While they continue to worry about minyanim and schooling, in large part their charge has morphed from a religious one to a humanitarian one. Many former Ukrainian Jewish breadwinners are now dependent on the community for heat, food, and warmth.

The winter has been freezing and dark, as Russia pounds civilian infrastructure. There are regular electricity and water shut-offs, rendering ovens, radiators, and washing machines useless. Sirens send families scurrying to bomb shelters, and the fear and uncertainty take a psychological toll. Kosher food is no longer being imported from Europe, and the shluchim have to make do with what is available locally. But none of that deters these families who are determined not to jump ship.

Five rabbis and rebbetzins serving Jews across Ukrainian war zones share snippets of their daily lives and how things have changed in the kehillos they toiled for decades to build.

Rebbetzin Devorah Leah Levenhartz

Location Kyiv, North Central Ukraine

Resident in Ukraine 25 years

T

he hardest moment for us was leaving Kyiv, and advising others to leave. We were leaving the only home our children knew, and the school we’d built up that catered to hundreds of children. We sheltered in our basement for a week after war broke out, but then we realized that the fighting was too severe for our young children and the other little ones in our community to cope with.

After a week, there was a short window of opportunity to leave Kyiv. Everybody who could leave left then, mostly to Israel, some to cities in Europe. We looked back at our homes and schools and didn’t know if we would ever return.

We managed to get to safety in Moldova, and then crossed the border to Romania, where Chabad arranged for us and many other refugees to travel to Eretz Yisrael. It was busy there. The Kyiv families needed our help — they didn’t speak the language, and needed help navigating bureaucracy and finding apartments and schools. We also kept in touch with those who chose European destinations, putting them in touch with local shluchim who could help them.

But some families could not leave Kyiv, and my husband and I soon realized we were needed back there. At first, we left our children in Eretz Yisrael. But the separation and the logistics of traveling out of Ukraine to visit them were so impractical. In the summer, we decided to bring our kids back to Kyiv.

It isn’t easy. There are sirens and rockets, and power cuts and shortages, yet they feel attached and rooted here. They were born here — it’s the only home they know, and it’s where their parents are.

True, most people have packed up and left. Not long before the war, we’d begun a ladies’ shiur. Now, every single member lives in a different place. But we meet regularly on Zoom.

There are only 90 children left in our entire school system now, including the day care and preschool divisions. On days when the media speculates there will be big attacks, some children stay home. The six other frum families who lived here have gone, so there is no more cheder or separate girls’ classes, and our own children now learn in Chabad’s online school.

The power grid was bombed into a fraction of its capacity this winter, which made things very difficult. Imagine no light, no washing machine, no oven, no heat. In most Ukrainian buildings, the gas cookers use electricity, so people couldn’t cook at all. Since the beginning of the war, we’ve been sending out hundreds of hot lunches daily to the Jewish families and elderly, as well as to fifty non-Jewish Ukrainian soldiers.

In some areas, there was no phone reception and no internet. We know an elderly woman who lives on the 14th floor of a city apartment building. She was often stranded up there, in the cold and dark, with no elevator and no way to cook. Yet she’s tough; it didn’t break her spirit.

War, and the constant threat of danger, affects everybody, but we Jews are so lucky that there’s a kehillah to support us. Our community now eats the Shabbos seudos together each week, and people come and draw strength. We made a beautiful women’s evening for Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka’s yahrtzeit, and 80 women came. One told me she had been in despair, “but now, I want to live again.”

We’re here to help the Yidden. If they want to leave Kyiv and settle elsewhere, we help them, but we’re staying here for those who can’t leave and need us. The bomb shelter in the shul and the generator we received from Chabad enable us to hold our community events with peace of mind, knowing we’ll have light and safety in case of sirens. We’ve had non-Jewish neighbors who want to come into the bomb shelter or charge their phones on our generator. That’s okay, too.

If you would have told me a few years ago that I would be living and working in a war zone, I wouldn’t have believed you. We live on a main road, and every year, on August 24, Independence Day of Ukraine, we would watch the jeeps and tanks parade by in celebration. I never thought I would see them in action. Yet, suddenly one day, there was a war on our doorstep.

Rabbi Yechiel Shlomo Levitansky

Location Sumy, North Eastern Ukraine

Resident in Ukraine 19 years

S

umy is a small city, with about 3,000 Jews. Before the war, our community numbered roughly 400 active members. It had a mikveh, a daily minyan, shiurim for adults, a preschool, and a children’s after-school program.

When Russia declared war, we realized we could draw on our experience running the community under lockdown. Many people here chose to isolate at home for endless months during the Covid pandemic, and we’d assembled a team of volunteers to keep the Jewish community together and given out phones, laptops, and tablets to keep everybody in touch. On February 24, we immediately got our volunteers together and went back into Covid mode.

The supermarkets and warehouses knew us, because we’d bought in bulk to help out our members during Covid, so we had direct access to the food we needed. But Sumy was under Russian siege, and after the first week, the supermarket shelves emptied. When we realized that the city lacked basic supplies, I knew that we couldn’t help anyone from the inside. I smuggled my family out of the besieged city, and — chasdei Hashem — we were able to leave Ukraine and reach Moldova.

The contrast between the horror of war and the human kindness was so stark. Non-Jewish locals in Poland showered us with free food and blankets and offers of sleeping space in people’s summer homes and empty apartments.

We were in Poland for three months, running a Chabad refugee hotel, where Jews from all over Ukraine had gathered. We also sent humanitarian aid to our community in Sumy, and once a humanitarian corridor was open, we organized buses to get people out from Sumy to Eretz Yisrael, Poland, or Germany. Over the next four months, we moved from Moldova to Romania, and then to Poland.

My kids are in the online Chabad school, so their school came with them wherever we were. They’re troopers, very brave. As parents, we try to keep our children out of the horror to a certain degree. We want to shelter them. But it’s there, and there’s only so much you can hide. During the first week of war, when the sirens screamed and everyone thought the Russians would be in our streets within days, my six-year-old and eight-year-old daughters sang Rabbi Ephraim Wachsman’s lyrics, “I believe in Hashem, I trust in Hashem….” Another child commented that he would be able to tell his grandchildren he’d lived through a war.

My twelve-year-old feels a commitment to the shlichus to such an extent that he didn’t want us to leave our people behind, even when the siege closed in. I think that the greatest strain was probably on my older children, who learn in yeshivos and seminaries all over the world, and were desperately worried about us.

Before Rosh Hashanah, the Russian army miraculously retreated. We went back home to continue our work, and many of the city’s residents returned too. While the city itself is pretty calm now, the outskirts get shelled almost every day. The rockets and shells, as well as the long-range missiles to further targets which fly over Sumy and sometimes get intercepted in the skies above us, make it impossible to forget that the Russian army is on the other side of the border.

We’ve been very busy since we returned. Our programs are running, besides the pre-school which sadly cannot open right now as it doesn’t have a bomb shelter. Some Jews who never responded to our outreach before the war, mainly from the age 30-50 demographic, have come forward. They’re asking for tefillin and mezuzahs, and even for me to come kasher their homes.

We’re giving out hot lunches and food packages to people who’ve lost their source of income, and emergency lights because there are constant electricity and water outages. Not only has our community become closer, the atmosphere in the entire city has become more friendly, as people try to look out for each other. Yes, there are no streetlights, and a curfew from 11 p.m. to 5 a.m., but there’s optimism and innovation, as people attune themselves to survival and hope.

There are no more kosher products from Europe sold here, and whenever a siren sounds, the stores close. On Erev Succos, we were expecting a lot of guests. We filled up a cart in the supermarket, but then the siren shrieked, the store closed, and then it was Yom Tov. We had to manage somehow.

The generators we were given make coping with electric outages easy. Water outages are more problematic. The water can suddenly go off for a few hours, or a day, or two days, and there is only a certain amount of water we can store.

Travel is complicated too. There are no airports in Ukraine during wartime, so traveling to the Kinnus Hashluchim, for example, meant driving for 17 hours to the Polish border, waiting anywhere between two and 11 hours to cross, and driving another three hours to the airport on the other side. It was worth it for me, though, because being the Rebbe’s shaliach is the motor that keeps me going.

Mrs. Miriam Moskowitz

Location Kharkov, North East Ukraine,

Resident in Ukraine 33 years

ON

February 23, 2022, we celebrated our school’s 30th anniversary. On February 24th, war broke out, and schools in Kharkov have not been opened since.

Kharkov is just 40 km from the border, and we’re constantly under rocket fire. Approximately 12,000 of Kharkov’s 25,000 Yidden are left here. Most people fled either to Israel or to Europe, and some went to safer areas in Ukraine. The other shluchim have left. We also left to Israel as soon as we could, but my husband kept coming back and forth, and before Rosh Hashanah, we moved the family back.

My children now belong to Chabad’s online school. My 12-year-old son helps my husband in shul, and my daughter is the only frum girl coming to shul. They’re more actively involved than ever, and they’re proud of their role. For Tishrei and Chanukah our older children joined us from their yeshivos and seminary.

By now people are starting to come back to Kharkov, not because things are getting better here, but because they miss their homes and familiar surroundings. While in general people here are pretty resilient and have a strong desire to keep going about their lives, we know of several Yidden who are being treated in the psychiatric unit. Especially for those living alone, the constant bombardment and attacks have worn down their psychological wellbeing.

A winter without streetlights was as dark as it sounds. From three or four p.m., the streets were pitch black. People don’t really walk around in the dark, which meant changing some shiurim to daytime. If you have to go out, you hold out your flashlight or your phone for safety, because otherwise cars can’t see you at all. This made the Friday night minyan a huge challenge, and our family hired a guard to walk us home from shul. On Chanukah, we couldn’t celebrate outdoors, so we held our public menorah lighting in the subway station, which is also Kharkov’s biggest bomb shelter, where 15,000 people lived at the beginning of the war.

Since the shul is a relatively safe building with a solid basement, 150 people moved in to live there last February. Thirty people are still living in that basement, too scared to go back home. Their homes have no heat, their windows are blown out by bombs, and they simply feel safer in the shul. In our home, we all sleep in our basement. We put up sandbags in the windows, so if the city is under attack in the night, we can stay where we are and not have to scramble for shelter.

Both our shul and our home have generators, because electricity is switched off for four or five hours a day, and if the power supply is hit by rocket fire, it can take a day until it’s running again. Over the year my kids have gotten a lot less fussy and we manage with the food we have, which at the moment is coming from our big generator-fueled freezers. One Erev Shabbos I had put up a challah dough when the electricity went out, and I sent my raw challahs and raw chickens over to the shul kitchen, which had power. Another time, right before Shabbos, we realized we had better open some cans of tuna. Still, we managed to keep up the Shabbos spirit.

I’m from Sydney, and my husband is from Venezuela, but we were sent by the Rebbe to be here for the people and to help each and every Jew. At five a.m. on February 24th, our shlichus changed. The focus on helping people with their Yiddishkeit shifted to helping them with their physical and emotional needs, keeping people alive with food and medicine and heat. It’s an awesome responsibility, and donors from all over have stepped in to help us.

There’s definitely been a religious awakening during this war. We have 70- and 80-year-olds coming to shul for the first time ever. It’s true that they want the food packages and heaters and medicine, but they also want to connect to the spiritual. The morning minyan is full of people who just want to feel the togetherness of the daily davening as part of a group. I give a weekly women’s class on Zoom, and we have some new ladies. After yet another week of sirens and blackouts, they need the light of encouragement and inspiration.

A month ago, a lady with a six-month-old baby and a four-year-old son asked us to arrange a bris milah. We brought a mohel over to Kharkov, and as the visit became the talk of the community, a fellow named Alex came forward. He only started coming to shul a few months ago, but he wanted to have the bris he’d never had. At 55, in the middle of a war, he was ready to enter the covenant of Avraham Avinu. Incidents like this keep us going.

Rabbi Shlomo Wilhelm

Location Zhitomir, Western Ukraine

Resident in Ukraine 28 years

AS

Zhitomir was the Jewish center of Western Ukraine, we took care of not only the 500 Jews who attended shul, but the 3,500 Jews in the city and those in surrounding areas, offering everything from bris milah to a beis hakvaros. We brought over couples to work with Yidden in the other cities of West Ukraine, and bochurim to make Yom Tov in the villages. Before the war, Zhitomir had forty children in a cheder, and 150 children in the Jewish day school, including sixty who were living full-time in the Jewish children’s home.

The Russian army pushed forward to just seven kilometers away. At the first rocket, the city was wracked by fear and panic, and we decided to get those children out. Three hours after war broke out, we packed the children onto buses and sent them in the direction of Romania. They crossed the border to safety, and 12 days later, were in the first group to be airlifted to Eretz Yisrael. The KKL charity hosted the group on a campus in the town of Nes Harim for six months, and in Elul, the children and their staff and families moved to Ashkelon, where we found schools that could absorb them.

Throughout this whole saga, I felt that the One Above was taking care of our children. We always found fuel for the buses and safe places to sleep, as if the children of Zhitomir were being transported on eagles’ wings to safety and a new life.

Our community here has also been taken care of, baruch Hashem. The people are okay, and the community buildings are still standing. I travel back and forth to take care of the needs of both those still here and those who have left.

For Yamim Tovim, I take my family back there. For my own children, this move is about realizing that Hashem has a plan. We had a job to do there, but if now our shlichus has changed — hal’ah b’simchah, we’ll go forward happily.

Many people have lost their jobs, and even for those who do work, the crazy inflation means that with their hryvnia wage they can buy about half the amount of food and supplies which they could before February 2022. They’re suffering great poverty. We organize humanitarian aid, giving out batteries, clothing, emergency lamps, gas heaters, and medicines.

The summer was pretty quiet, but the fall began with Russia knocking out the gas and electricity. At the moment, curfew is in place and street lamps are off from 12 a.m. until morning. There are frequent power outages, leading to blackouts with no running water or heating. Over 500 families in the city receive regular packages of either dry foods, or hot cooked food, and we also arrange for wood to be supplied to the households outside the city who use wood fires for warmth.

The shul still has a regular minyan, mainly of old people, and 35 children from 18 families still attend Zhitomir’s Jewish school, often spending a large part of the school day in the bomb shelter, due to sirens. The shelter was renovated and decorated to make it as cheerful and cozy as possible. Living in the shadow of a war has a definite impact on mental and emotional health, and we do everything we can to provide them with a happy, busy, fulfilling program, so they can still be children. Although the fighting is far away in the east, there are still unpredictable sirens, soldiers in the streets, the pressure of not knowing what will happen next, and a steady stream of bad news. Obviously, it has an effect. It’s not simple.

I feel very much encouraged by the generosity of all those who are contributing to our efforts. Although supplies have been low at times, the food sent by our Jewish brothers means our community hasn’t gone hungry. Your contributions help give us strength to continue.

Rabbi Avraham and Rebbetzin Chaya Wolff

Location Odessa, South Western Ukraine

Resident in Ukraine 30 years

T

he situation in Odessa really isn’t so bad. A year ago, we thought Russia would quickly win the war, and we would be under Russian governance, but, baruch Hashem, our city is still Ukrainian, and in fact, it’s so quiet that we’re bringing our children’s home back to Odessa from Berlin, where they were evacuated last February. We think it’s time to come home. The Russians keep threatening new offensives and different tactics, but we believe in Hashem’s miracles.

It’s busy here, so that we don’t have too much time to think about what nebachs we are, living through a war. The Rebbe sent us, and we’re here to help the Jews with whatever their needs are. If someone wants to get out and go to Eretz Yisrael, we help him, and if someone wants to stay here, we help him too.

The shul and the community kitchen in Odessa stayed open the whole time. We’re still cooking the same amount of meals daily, but while we used to serve 1,000 children in the schools, a lot of the meals are now delivered to the elderly.

The food situation is reminiscent of what it was like when we came 30 years ago as a young couple. You have food because you buy potatoes, cabbage, and onions, but you don’t have snacks or kosher spreads and jelly for your bread. Kosher milk is difficult to come by, as it was back then. In recent years, Odessa sprouted three kosher groceries and five kosher restaurants, but now only one store and one restaurant remain open, and the variety of products they used to import from Europe has vanished.

At the beginning of the war, communities in London and Paris shipped us containers of every food we could want, like long-life milk, kosher cakes, crackers, candy and tuna, but the supply finished summertime. Now there’s only what is here. Still, no complaints; our pantries aren’t empty. Generators were sent to keep our big freezers running; since chicken and meat are only shechted once every few months, at the moment, they’re absolutely vital.

Thirty percent of our people are still here, and we provide everything for them: minyanim, a full day of preschool and school, as well as humanitarian aid — packages of oil, rice, sugar and macaroni — to ensure that every family has food to eat. This humanitarian work wasn’t necessary previously, because people had jobs, but many people can’t work due to the situation.

We used to have local donors, but now businesses have closed and the businesspeople are gone, and the money is coming from all over the world instead. One of our most expensive projects is our “Jewish University,” an arrangement we negotiated with the University of Odessa to have their lecturers come and teach our students degree courses, and we continue to maintain it for those who are left here. After being nurtured and educated from age one to age 17 in our Jewish institutions, it’s crucial that the kids shouldn’t be thrown into a non-Jewish environment and meet non-Jews. Over 50 couples who are both graduates of our university have married and set up Jewish homes.

Our son learns in the online school, as always, but I think he’s matured a lot. Being a child of war does that. You can’t remain in shock for a year. We can see how people have pulled themselves together, and many Jews who were never drawn to shul have started to come. Last year Purim and Pesach events drew in more people than expected, as did Chanukah this year.

The word spread that the synagogue has a generator, so people constantly drop in and sit down to warm up and charge their phones. Everybody wants a warm word and to hear what the rabbi has to say, and they come here to feel part of something that is bigger than they are. They know we’re here for them, even if what they need is a shoulder to cry on.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 951)

Oops! We could not locate your form.