From the Heart to the Heart

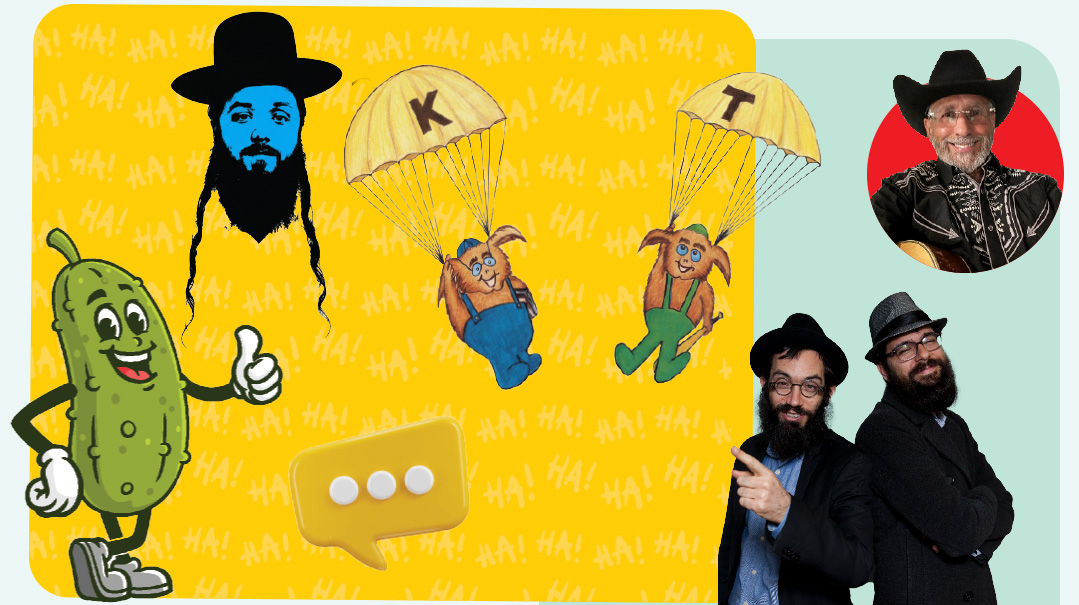

| April 25, 2023Musical colleagues mourn Yiddish composer and singer Michoel Schnitzler

The passing of Yiddish composer and singer Michoel Schnitzler a”h on Isru Chag Pesach was a tragic loss for the Jewish music world. Michoel was gifted with a rich baritone and dynamic stage presence that electrified crowds at thousands of weddings over the years, and was a trailblazer in contemporary Yiddish song, leaving behind 15 albums produced over almost 30 years. While his ballads could be wrenching, his warmth mended many a broken heart. Colleagues in the music industry share their memories

Naftali Schnitzler

“He never said no”

Michoel was both my uncle and my musical role model. He was very warm and devoted to the family, and when he saw I was interested in music, he bought me my first keyboard.

He shone as a performer, with a presence that would transform a crowd and create incredible energy. These days, with the dance music so loud and the beats so fast, maybe a wedding singer has an easier time getting the dance floor pumping with joy. But back when he started out, Michoel, who was one of the first chasunah singers, had to work hard, to push with everything he had. Yes, it’s true that the very first time he sang at a wedding, he faced the wall rather than the crowd. But when he turned around and saw how the men were dancing, he realized this could be a game changer.

Not only was Michoel the first to sing through the entire dance set at weddings, he was an innovator in developing the musical potential of vocals. In the days before professional sound technicians arranged sound systems at frum weddings, Michoel figured out on his own how to optimally manipulate the microphones and amplifiers. Then he took it further. Years ago, he was at a wedding in Monsey, and the chuppah was delayed. While waiting, he went into a local music store and asked them if they had any equipment that could give a singer’s voice some extra effect. So they gave him a guitar effects pedal, something commonly used by guitarists to alter the sound of their instrument by changing the waveform of the guitar signal — for example, to make the sound delayed, sustained, or reverberating. He took it, and, on his own, figured out how to use it while singing. He was almost certainly the first vocalist in frum Jewish music to use an effects pedal, but others emulated him, and to this day we use it when professionally mixing music. But more than that technical skill, what he brought to a wedding was the infectious simchah, the energy of his stage persona, and magnetism of his delivery.

Michoel’s debut wedding music album, A Yiddishe Simcha, was released in 1994, and by 2000, his first Yiddish album was out there, creating a new niche in music. Two entire albums are on the theme of Shabbos, which he was deeply connected to, and his petirah occured very, very close to his beloved Shabbos. He was a deeply emotional person, and I still cry when I listen to “Yesimcha Elokim,” from his first album of Shabbos songs.

Like many frum singers and performers, Michoel was often called to bring light into hospital rooms. Organizations and individuals asked him to come sing, knowing that he could make people smile, that there was an infectious joy that could make a world of a difference to a sick child or housebound adult — or even to someone who could just use some attention. He never said no.

Moshy Kraus

The bottom line was putting a smile on someone else’s face

Michoel Schnitzler opened up the industry for wedding singers and chassidish albums, so many artists and performers today can thank him for jumping in. The songs he made popular touch people in their deepest places, and while “A Lechtele” (written by Pinky Weber, about a woman who’d been mourning her son since the war and decades later discovers he’s still alive) is probably the most well-known, there are dozens of songs he brought to the world which are widely sung today.

Around 12 years ago, before I knew Michoel well, I made a parlor meeting to raise money for a certain cause (this was before crowdfunding campaigns existed). It was held in my studio, which was new at the time, and I invited a lot of popular people in the music industry. Well, I don’t remember exactly who came, but not many. Things were pretty quiet. And then suddenly there was Michoel Schnitzler sitting next to me. He had driven for two hours to come and join me and be mechazek me as I tried to fundraise. The event was a success thanks to him. He greeted each person, including children and teens, like an old friend with whom he’d lost touch.

I got to know Michoel up close when I produced his Miyemini Michoel album in 2018. It was after he had almost left This World but then survived major heart surgery. We were almost ready to release the carefully crafted project when he called me up and told me he needed to add another song, that it was not up for debate. “Someone wrote it for me,” he said, “and that person will feel very good if it goes onto the album.” It really was not shayach to add a song, but he had the final word, so we did it anyway. I wasn’t thrilled at the time but I had to accept it, because Michoel would do anything to avoid hurting someone.

It wasn’t long after the album was released that I was producing and managing the music at a wedding, while Michoel was performing as the singer. The orchestra had just started playing the intro to one of Michoel’s new songs, and I was excited for him to sing it live, planning to post a clip and create more of a “matzav” around the song. Then someone else came on stage — and Michoel handed him the mic. “Go for it!” he said. Afterward I said, “Michoel, what were you doing? It was going to be big!” And he said, “Didn’t you see the happiness, the chizuk that guy got?” Because for him, that was the bottom line. Nothing was more important than putting a smile on someone’s face.

Motty Ilowitz

He made sure each song was encouraging, empowering, and meaningful

Michoel Schnitzler was both a humble and a gentle giant. Those who heard Michoel sing on stage at a wedding, or at his live recordings, got their songs interspersed with greetings called out to his many friends and acquaintances. Up there on stage, he was scanning the crowd, picking out people who could use a good word over the mic, saying things like “Hey, Hershele!” and “Sruli, tzaddik!” He was everyone’s best buddy and loved making people feel special. You never saw him without a smile, even though he had plenty of painful moments in his life. Every voicemail from him starts and ends with a compliment — “Hello, Motti tzaddik… love you, tzaddik.”

I wrote over ten Yiddish songs for Michoel and sang duets with him. I owe him big-time for being the first one to hire me as a badchan for a mitzvah tantz. No one knew me at the time — I didn’t even know myself — and I didn’t know I was a badchan. Lipa Schmeltzer had introduced me to Michoel Schnitzler, and I had written one song for him, but I wasn’t in the music industry then and I’d never performed. But Michoel hired me for his daughter’s wedding, pushing me to push myself and take the job. I don’t know many people who would have given the mic at their daughter’s chasunah to a completely unknown, untested badchan. Baruch Hashem it was a successful night and the recording got out there and took me places.

Michoel wasn’t the first to sing Yiddish ballads. Twenty-five years ago, Yiddish-speaking homes had Yom Tov Ehrlich and Yonason Schwartz’s tapes, but Schnitzler was a little different. He hired top contemporary composers to write for him, and he brought out long, epic songs, which lasted eight to ten minutes, expressed a story and brought it to life in a powerful way. He was particular that each song should be encouraging, empowering, or make a meaningful impression. He used to call me to make small changes to the lyrics, making them better and stronger. The material is warm and heimish, and when you listen closely, you can sometimes hear Michoel cry.

Lipa Schmeltzer

“He was a very real person, who knew how to laugh and how to cry”

IT is so hard for me to speak of Michoel in the past tense. We were as close as brothers — I tore kriah when I heard the news, and I gave a hesped, like a family member.

It’s been a long journey since that day when I was a young bochur and Michoel was the very first one to by a song from me. We visited many hospital patients together, and sang many a mitzvah tantz together, with me singing grammen and Michoel harmonizing. We also spent many Shabbos meals together. I watched him go through many difficult and challenging times with family, health and other issues— he told me about one Erev Pesach when he had nothing in the house at all, until someone realized his situation and gave him a cash gift. He raised his children at a time when being a singer was not considered a respectable parnassah in the chassidish world, and he suffered for it. He was a very “real” person, who knew how to laugh and how to cry, but through all his ups and downs, he was not embittered and never complained.

His music succeeded because he could intuit the messages this generation thirsted for, messages of positive energy and hope and renewal even when things seem bleak. I cannot believe that he is no longer among us, but his music certainly lives on and will continue to uplift and encourage.

Velvel Schmeltzer

“No personal troubles could stop him from being nice”

Three weeks ago, on Chol Hamoed Pesach, I ran a podcast on Kol Mevaser called “My First Job,” which brought some well-known music artists back together with the first client who hired them. Michoel Schnitzler was featured, together with Reb Yaakov Leib Friend. Thirty-two years ago, Reb Yaakov Leib heard Michoel sing at a Simchas Beis Hashoeivah, and was so impressed that he begged him to sing at his own child’s wedding in Brooklyn. At the time, every wedding had a band, and sometimes someone would get up and sing a slow song — Isaac Honig did that — but no one was at the mic during the dancing. Michoel said, “Do me a favor — I am not singing at a wedding,” but Reb Yaakov Leib Friend pushed and pushed. Michoel took a mic, but he was much too shy to face the crowd and sing, so he turned to the wall.

In the interview, I questioned Reb Yaakov Leib Friend about their relationship: “You were the first one to trust him,” I said. “If you could make a request of Michoel today, what would you ask him?” Friend responded that he would ask Michoel to sing for a relative of his, a broken woman. Michoel’s response? “I can tell you one thing: I’m ready.” On Isru Chag, Friday, Michoel told his nephew that on Motzaei Shabbos, he was going to sing for this lady, as promised on Kol Mevaser.

The first song on Michoel’s albums was always an upbeat, happy, dance song, and the second was usually Holocaust-themed. He sang several heartrending songs about World War II, because he felt it very deeply; his parents were survivors. Pinky Weber composed a lot of the material in early years, and it became very popular. His song “A Lechtele” is often used in shul for Mimkomcha since Abish Brodt popularized that, and you’ll even find rebbes and elderly Yidden humming along — a true honor for a niggun.

No personal troubles could stop Michoel from being nice to people. He was orphaned of his father when he was young, and tried to reach out to yesomim with his own brand of encouragement and chizuk. Yonason Schwartz, who accompanied Michoel on countless hospital visits, remembers his mission to spread happiness. Once, while Michoel was sitting and chatting at a child’s bedside, the chair he was on collapsed and he went down suddenly onto the floor. The child couldn’t contain his giggles and Michoel loved it. So Michoel took the chair to the next patient’s room, stuck it together, and let himself fall down again. He repeated the joke until he was aching, and a few sick children were happily laughing. Famed composer and badchan Pinky Weber, who was a close friend of Michoel through decades of collaboration on Yiddish songs, expressed it like this: “It’s not a chiddush that Michoel could put a smile on everyone else’s face. But the fact that he could put a smile on his own face — that’s a chiddush.”

When my brother Lipa was just a kid of 19, he called Michoel Schnitzler and asked if he could listen to a song of his. Who would trust him at that time? No one besides Michoel Schnitzler, who bought the song from this unknown teenager and released it on his next album. At his levayah, Lipa cried out, “Michoel, you trusted me. I’m standing here today in my hat and rekel because of your trust and chizuk. And what will happen to those confused or alienated teenagers of today, now that you’re no longer here?”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 958)

Oops! We could not locate your form.