From the Ends of the World

| October 6, 2022In Rabi Yekutiel Abuchatzeira’s court in Ashdod, he sees them all — the ones who are trying to climb, and the ones who feel like giving up

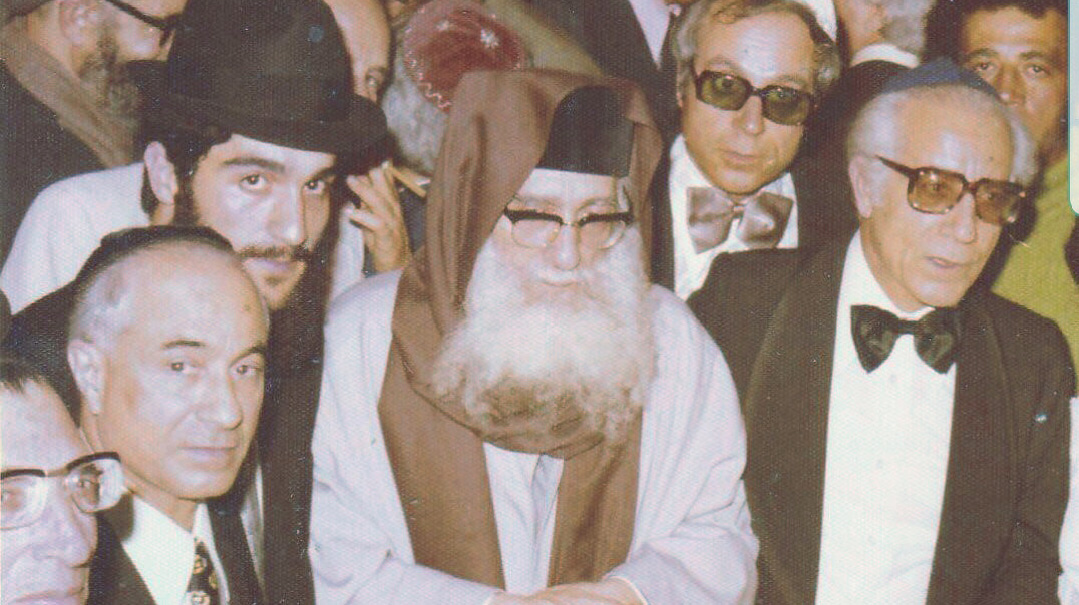

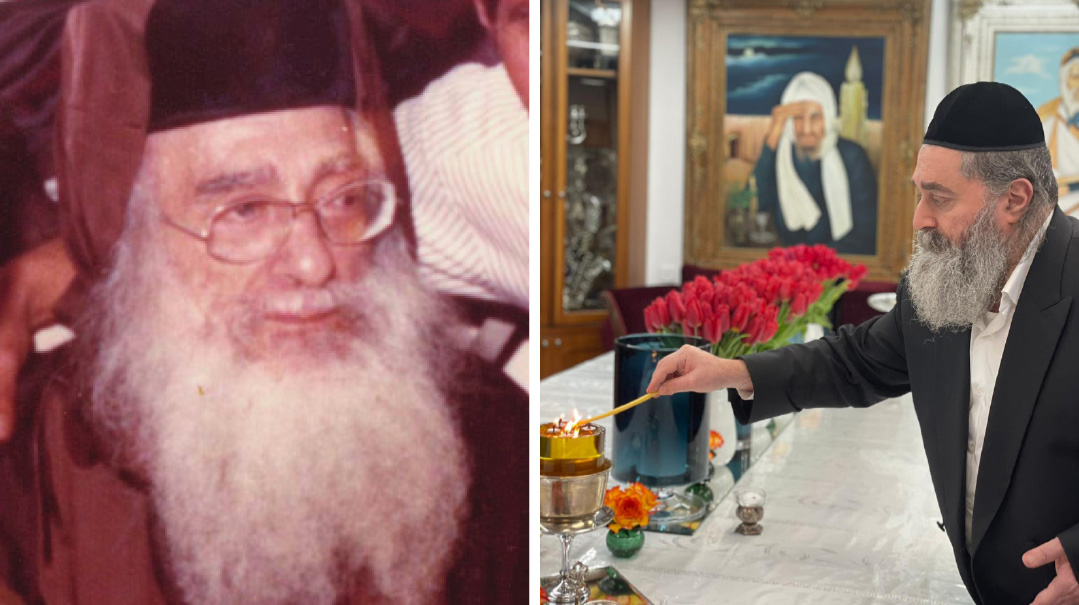

Photos: Elchanan Kotler, Mishpacha archives

“You will meet the Admor in the classroom,” I was told.

“The classroom?”

“Yes, the classroom in his Talmud Torah in Jerusalem.”

“In Jerusalem?” Now I was even more confused.

Rabi Yekutiel Abuchatzeira — scion of the famed family and a rebbe in his own right — is a renowned tzaddik who leads mosdos and a popular court in Ashdod. Followers of many different stripes and types make their way to the oceanfront city to seek his counsel on matters ranging from spiritual directives to business decisions to medical dilemmas.

But our conversation takes place in a more unconventional setting, especially considering the stature of our host: Instead of his Ashdod beit medrash, which attracts a colorful crowd of Sephardim as well as many Gerrer, Vizhnitz, Satmar, and other chassidim from both the city and further afield, we’re sitting on plastic chairs in a Talmud Torah classroom in Jerusalem. Rabi Yekutiel is just as comfortable here, though — in Ashdod, too, he sits on a simple bench among his diverse crowd of mispallelim.

The cheder, which Rabi Yekutiel opened a few years back on the campus of Yeshivas ITRI in Jerusalem’s Talpiot neighborhood, is part of the Chazon Meir U’Beit Yisrael network of mosdos established several decades ago in memory of Rabi Yekutiel’s holy father and grandfather — Rabi Meir and Rabi Yisrael Abuchatzeira (the Baba Sali).

With 1,200 students in the Ashdod mosdos and another 200 in Jerusalem, Rabi Yekutiel says it “uplifts his heart” to perpetuate institutions bearing the name of his great forebears.

In a way, it’s a return to the source, because from the time Rabi Meir Abuchatzeira arrived in Eretz Yisrael in 1966, the famed Moroccan rav and rosh yeshivah refused to have talmidim, at least in an official capacity. After turning down an offer to be chief rabbi of Jerusalem, he moved to Ashdod, where he lived in purity and isolation until his petirah in 1983, predeceasing his father, the Baba Sali, by a year.

“In Morocco,” recalls Rabi Yekutiel, “my father sat with talmidim from early morning until night and demanded the maximum from them. They started their day at midnight with Tikkun Chatzot, studied Kabbalah until Shacharit at dawn, then continued on to Shas, in order, daf after daf, and at the end of the day they studied Shulchan Aruch.”

Rabi Meir was continuing the legacy that his great-grandfather, Rabi Yaakov Abuchatzeira (known as the Abir Yaakov), founded in his home in Tafilalt, Morocco, 180 years ago. “Since then,” says Rabi Yekutiel, “kol yotzei yerech Yaakov — all his offspring followed in his footsteps.”

From his beit medrash in Ashdod and network of schools, Rabi Yekutiel Abuchatzeira teaches the lessons of his holy forebears. “Don’t hold grudges, don’t get upset, and overcome your anger”

The Man Who Bent Nature

In Abuchatzeira terminology, “yotzei yerech Yaakov” refers to the offspring of the head of the dynasty, the Abir Yaakov. The Abir Yaakov, considered the patriarch of the Abuchatzeira dynasty, was buried in Damanhour, Egypt, after he fell ill trying to reach Eretz Yisrael. His descendants remained in Morocco, where they spread Torah around the country.

His son Rabi Moshe (Masoud) became rav of Tafilalt, Morocco, and Rav Moshe’s children — Rabi Yitzchak (known as the Baba Chaki, who became rav of Ramle), and Rabi Yisrael (the Baba Sali, who eventually settled in Netivot), essentially moved the dynasty to Eretz Yisrael. (A third son, Rav David, who succeeded his father as rav of Tafilalt, was horrifically murdered, propped up in front of a cannon in a Rosh Hashanah pogrom in the city in the 1920s.)

Throughout the years, many miracle stories have been attributed to the tzaddikim of the Abuchatzeira family, and especially to the Baba Sali, whose acts of bending nature often revolved around a bottle of arak at the hilulot of tzaddikim or at seudot marking other special days.

The Baba Sali originally made aliyah in 1951, intent on hiding his identity, although when he was discovered, he was offered to be the country’s chief rabbi. He declined, returning insteead to Morocco intent on strengthening religious life there, which had severely deteriorated. He returned from Morocco to Eretz Yisrael for good in 1964, settling in Netivot.

The Baba Sali’s oldest son, Rabi Meir, followed with his family in 1966. Before that, Rabi Meir was considered one of Morocco’s greatest sages. He knew all of Shas and poskim by heart, and even served as rosh yeshivah of a Lubavitch yeshivah, maintaining a close connection with the Lubavitcher Rebbe. He maintained close ties with gedolim around the world, and was also known to be meticulous in the mitzvah of guarding his eyes.

Rabi Meir and his wife Simcha had nine children together, four sons and five daughters. Those sons would all become admorim in their own right: Rabi Elazar ztz”l in Be’er Sheva, Rabi David in Nahariya, and Rabi Refael and Rabi Yekutiel in Ashdod.

Rabbanit Simcha passed away in 1965, leaving nine young orphans, and Rabi Meir then married Rabbanit Mazal, who bore him another son, Rabi Yeshuah Verachamim, today a rosh kollel in Ashdod.

Total Control

Rabi Meir and his family made aliyah in 1966 (Rabi Yekutiel was six years old at the time), but although his great name preceded him, he refused any public position, remaining largely hidden from the public until his passing. However, he was known to other talmidei chachamim, who sought him out, knowing what a treasure was to be found in the humble abode near the sand dunes in Ashdod, then a small town with little Yiddishkeit.

“People marvel at how Abba reached such heights, and how he saw from one end of the world to the other. It was because he was connected to Torah with all his senses,” says Rabi Yekutiel. “That’s why the geonim of the previous generation would make regular visits to him. Rav Chaim Kreiswirth of Antwerp, who was a regular visitor, would say, ‘He’s not only an expert in the Torah forward, he also knows it backward, line after line, from the end to the beginning.’ He was in touch with gedolim from all over — the Satmar Rebbe, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rav Itzikel of Pshevorsk, the dayanim on the Eidah Hachareidis, the Minchas Yitzchak — who not?

“Every so often, Rav Ben Tzion Abba Shaul would visit. He’d arrive agitated and leave happy, his questions resolved. My father would simplify all his questions, as if he were taking the answers out from under the Kisei HaKavod.

“So why, then, didn’t he teach talmidim like he did before he came to Eretz Yisrael?” Rabi Yekutiel continues. “I believe the answer is that when they came to Eretz Yisrael, my father and grandfather chose places to live where they could closet themselves. My father came to Ashdod 56 years ago, when you could have counted the buildings in the town on one hand. Likewise, when my grandfather the Baba Sali moved to Netivot, the entire town had two streets.

“In chutz l’Aretz they had disseminated Torah in the yeshivah, instructing the masses in halachah and supervising the rabbanim of the city. But in Eretz Yisrael, they wanted to purify themselves without anyone knowing who they were.”

It didn’t exactly work, though. They were discovered, and people from all over streamed to them, even though they didn’t accept any official position. Still, the Abuchazteira rabbanim had led yeshivos in Morocco for over 200 years. Why didn’t they open a yeshivah?

“I believe they wouldn’t do it unless they could maintain the standards our holy fathers maintained,” says Rabi Yekutiel, who was himself an avreich for many years until he opened his beit medrash. (His older brothers Rabi David and Rabi Elazar a”h became leaders in their respective cities during their father’s lifetime.) “Any yeshivah they ran would have had to adhere to all the practices, rules, and demands that they deemed essential — but that our generation finds hard to understand, let alone follow.

“And it wasn’t only related to talmidim. In Morocco, they had total control of every aspect of Jewish life. Their supervision was very tight — they oversaw chinuch, boundaries of holiness, kashrut and shochtim. They strenghtened observance of Shabbat and monetary laws. But here in Eretz Yisrael, with all the state regulations, it wasn’t for them, even though both of them were offered the highest rabbinical positions.

“I remember when a group of gvirim from England came to my father and pleaded with him to open a yeshivah like he had in chutz l’Aretz. They promised to fund everything for the next 20 years, but he refused. They told him, ‘Sidna [an Arabic title for a tzaddik], we will even buy you your own apartment.’ He refused that as well. Where did he live? On the third floor of an Amidar public housing building. Every month, he paid Amidar 100 shekels in rent.

“But he conducted himself in the same way as his holy father, the Baba Sali, who also lived on the third floor of a small apartment in a public housing project. Only toward the end of his life, when they built the yeshivah in Netivot, did he agree to move into a small residence there.”

With such an ascetic father and a large family, did Rabi Yekutiel experience grinding poverty as a child?

“I wouldn’t say poverty, because there was brachah in the house, in everything,” Rabi Yekutiel remembers. “We didn’t feel that we lacked a thing. Material items were never a focus. And that is the real brachah in a home — when its inhabitants feel they aren’t lacking anything.”

Rabi Yekutiel lights a flame for the neshamah of his grandfather, the Baba Sali, who shared a connection with his son that defied nature

Nothing Hidden

Reb Avraham Cohen of Netivot relates the following story: He once came to the home of the Baba Sali to ask for a brachah for children. The Baba Sali turned his face to the wall, pointed to it, and said, “Your yeshuah will come from here.” His finger wandered along the length of the wall, until it reached the window, and he pointed to a vehicle approaching from the end of the street.

Reb Avraham looked at the car, and Rabi Meir emerged. His father, the Baba Sali, smiled. “Here is your yeshuah. Go to him and he will send you salvation.”

Rabi Meir was already at the entrance of the building, enveloped in his cloak, and Reb Avraham pleaded for a blessing. Rabi Meir laughed, waved his five fingers in the air, and said, “You will have, you will have, you will have!”

From that point on, the Cohen family grew and grew — eventually reaching fifteen children. Rabi Meir had granted a three-fold blessing with five fingers, yielding the number fifteen.

But it was more than that. Rabi Meir seemed to know everything — nothing could be hidden from him, in either the physical or spiritual realm.

“Not only did he see everything,” says Rabi Yekutiel, “but in the morning, he would even tell us what would happen over the course of the day.”

The family had no phone, but still, Rabi Meir would announce that a certain person would be coming in the afternoon, and such-and-such would take place in the evening. And the events of the day always bore out his predictions.

“It really didn’t surprise us,” says Rabi Yekutiel. “We grew up with it. At the time we didn’t feel that there was anything unusual about it. We knew that our father was a tzaddik, and tzaddikim know everything — we didn’t make a big deal out of it.

“In fact, my father did know everything, not only what was happening in his immediate environment, but in the whole world. People came to him from England or Belgium, places where he’d never been. He described to them what their house looked like, what color the doorpost was, and how many windows there were on each side. His vision was boundless, because that’s what happens when one becomes a vessel for boundless kedushah.”

Rabi Yekutiel attributes his forebears’ incredibly far-reaching vision to their shemiras einayim and shemiras hamachshavah. For 40 years in Morocco, Rabi Meir was so sheltered that he did not see any woman other than those in his immediate family. From morning to night, he taught Torah to his students and saw nothing beyond that.

Rabi Yekutiel (L) with brothers Rabi Refael and Rabi David. “Our father would demand a lot of us. There was a closeness, but also real yirah”

Worried for Me

With such a father, I presume it must have been impossible for Rabi Yekutiel to misbehave or engage in childish mischief.

“True,” he admits. “I never played, ever. I didn’t own a bike or any other toy. We were always next to my father or grandfather. But we never felt like we were missing out. Next to them, there was a sense of the Shechinah hovering so tangibly that even we as young children could feel it.”

Yet that intensity came with its own set of obligations.

“My father would demand a lot of us, my grandfather even more. From a young age, we rose at haneitz, and they expected us to learn properly, to review what we’d learned. My grandfather would stand over us during tefillah, instructing us — ‘this is how to have kavanah, this is not how you pray.’ There was closeness, but there was always a fear next to them. It was genuine yirah.”

From the age of 11, Rabi Yekutiel went to Jerusalem to study in Yeshivat Porat Yosef, returning home only for the holidays. But he knew he had his holy father’s support.

“I knew that my father was thinking of me and worrying about me. He would send tzaddikim to visit me in yeshivah, and that gave me chizuk. For example, there was the mekubal, Rav Yosef Waltuch, a member of the group of hidden tzaddikim in Tel Aviv who earned their living from manual labor while secretly gathering together to learn Kabbalah. He was known as the ‘Street-cleaner’ and was very close to my father. I would ask him, ‘Why did you come?’ And he would say, ‘Your father told me to come spend some time with you.’”

A few years later, Rabi Yekutiel transferred to Yeshivat Hanegev in Netivot, at the behest of the Baba Sali who wanted him close by. Being in the constant presence of his holy grandfather was transformative for the young bochur, but admittedly not easy.

“With my father, we at least knew we were in our own home, but with my grandfather there was tremendous awe, and tangible fear of the gilui Shechinah.”

During the time that Rabi Yekutiel was learning in Yeshivat Hanegev, his father would occasionally travel to Netivot to spend Shabbat with the Baba Sali.

“He would come with my younger brother, Yeshuah Verachamim, who was just a little boy then, as my other brothers were all married,” Rabi Yekutiel relates. “It would be just the four of us sitting together — I can’t even describe the levels of kedushah we boys felt.

“The holy Shomrei Emunim Rebbe ztz”l once told me about the first time he visited my grandfather. He heard that there was a tzaddik in Netivot with a son in Ashdod who was also a tzaddik, but he didn’t believe it.

“ ‘I myself am the son of great people, and I knew the tzaddikim in Yerushalayim. I didn’t think I’d find anything special in Netivot or Ashdod,’ he told me. But he went anyway, taking along a group of talmidei chachamim who had prepared notes with complicated questions.

“In the end, they never even consulted their notes. The Baba Sali saw it all and addressed it all — even the note that was in the Rebbe’s own pocket.”

To Elevate a Child’s Soul

To our modern-days ears it sounds like a very demanding upbringing, but it proved to be the path to greatness for all of Rabi Meir’s five sons. They each eventually gained renown as special mashpi’im with many followers. They grew up in poverty, without their mother, yet they all forged themselves into great men.

“Knowing who my father was, people assume his chinuch was harsh and strict. As if it was only about rebuke and complaint. But my father knew how to elevate the soul of a child. I was one of the younger ones at home, and there was always a sense of happiness and strength in the house. We perceived the tremendous joy and serenity that my father exuded, together with boundless love that we all felt. There was a genuine and pure, unbounded joy.

“I remember that Rav Shmuel Wosner would visit once a month. One time, my father apologized and asked him why he made the effort to come from Bnei Brak to Ashdod. Rav Wosner answered, ‘When I need chizuk in yiras Shamayim, I come to visit the Rav.’ Do you think my father give mussar to Rav Wosner? Of course not. Just sitting in his presence would elevate the soul.

“Especially during this time of year, on the days after Yom Kippur, he radiated a level of joy that can’t be described. On Chol Hamoed Succot, people would come from morning to night to be able to sit in the succah three flights down from our apartment. They wanted just to be with him and bask in the otherworldly illumination that we thought was so natural. There were chiddushim and wisdom. They sang piyutim, and you didn’t feel like the time was passing. Twelve hours, fourteen… it was like being on another planet.”

In a revealing conversation with Mishpacha’s reporters. “I always knew my father was thinking of me and worrying about me”

Still Waiting

Today, all types of people find their way to Rabi Yekutiel’s beit medrash, many of them intense spiritual strivers. And they want to know: If an avreich wants to strive for the levels of the Baba Sali or Rabi Meir, is he striving for something simply impossible in these times?

Rabi Yekutiel ponders the question: “Rav Wosner said in his hesped that my grandfather was like a Tanna, and my father was like an Amora, and that feels very far from us. But I say, on the contrary — if in the last generation such holy souls were with us, why should Hashem not bring them down again in this generation?

“Many bnei aliyah — serious avreichim who want to grow and be elevated — come to me. They sit and toil in kedushah and purity, and they seek guidance regarding lofty concepts in avodat Hashem. They sit and learn day and night, and pour out their hearts in tefillah. Yet in this generation there are so many disturbances and distractions, ruinous elements that we never faced before. It is a generation of breaches, of nisyonot, may Hashem protect us from them. But on the other hand, those nisyonot can also create much more siyata d’Shmaya.

“For example, when my father came to Eretz Yisrael and wanted to live in Ashdod, people tried to dissuade him.

“ ‘What does the Rav have in Ashdod?’ they asked. ‘There are no frum Jews there.’

“And he said to them, ‘Trust me — in time it will be like Yerushalayim and Bnei Brak.’

“When the Gerrer chassidim came to settle in Ashdod, the Lev Simchah told them that it’s a good idea to live in Ashdod because my father lived there — and look what you have in Ashdod today, a city filled with Torah and mitzvah observance.”

Along with the far-reaching spiritual vision and demanding standards, a crucial part of the Abuchatzeira formula for greatness is a heart that beats with emotion and compassion. And that, perhaps, is the crucial reason that so many people appeal to Rabi Yekutiel for guidance.

A fellow once came to Rabi Yekutiel to share his troubles. He had purchased an apartment as an investment in Haifa, but the tenant wasn’t paying rent.

“Kevod HaRav,” the landlord complained, “The rental income is meant to cover my mortgage. I can’t afford this. I want to evict him from the apartment, but it’s not simple. The Rav should bless me that I should succeed in getting him out.”

“And where will the tenant go?” Rabi Yekutiel asked.

“As far as I’m concerned, he can go into the street.”

Rabi Yekutiel was silent. Then a tear rolled down his face, and then another and another.

The landlord was shocked. “Sidna, please don’t cry! This person is a mechallel Shabbat, it’s not a mitzvah to have compassion for him!”

The Rav gripped the landlord’s fingers. “It is not for him that I cry, it is for me that I cry. All my life I’ve pondered the fact that HaKadosh Baruch Hu gives us so much. We have health and food and a roof over our heads — we lack for nothing.

“We must be paying some price for all that abundance. We’re supposed to pay rent to HaKadosh Baruch Hu for what we receive in this world. Perhaps you pay HaKadosh Baruch Hu, but I know myself and how distant I am — I barely pay one percent of what I owe. So what would I do if HaKadosh Baruch Hu decided to throw me out of this world and told me, ‘Yekutiel, you are not paying Me rent, get out of My house…’

“So listen to a good piece of advice: Don’t throw him out. Leave the tenant where he is. Tell HaKadosh Baruch Hu that you are having compassion on him, and therefore He should have compassion on you.”

Today, everyone who comes to Rabi Yekutiel knows he’ll strengthen them in this area: Don’t hold grudges, don’t get upset. Overcome your natural tendency to anger, even when you’re sure you’re being grossly wronged. Because in the end, none of us is worthy.

Like his father before him, Rabi Yekutiel doesn’t fall into any category. He’s close to the gedolim of both the litvish and chassidish worlds

Bond beyond Worlds

The bond between the Baba Sali and his holy son Rabi Meir remains esoteric to this day. Often the Baba Sali would ask to be taken to Ashdod on the spur of the moment. Without anyone informing Rabi Meir that his father was about to arrive, he was already waiting on the sidewalk.

These encounters were enveloped in mystery. Father and son would gaze at one another for a long time, without uttering a word. Sometimes tears flowed from their eyes. At the end of the encounter, Rabi Meir would kiss his father’s head and hands, and then part from him.

The holy Baba Sali also foresaw the sudden passing of Rabi Meir on Chol Hamoed Pesach of 1983. From his home in Netivot, he felt everything, and refused to begin Shacharis. He demanded that the minyan start without him, and an hour later, the news of the passing came — the Baba Sali had become an onein and was not allowed to pray.

When Rav Yosef Waltuch came to the home of the Baba Sali right after Rabi Meir’s passing, he whispered in the Baba Sali’s ear, “Aha, Sidna, ruach apeinu Mashiach Hashem” — an acronym for “Meir.”

The Baba Sali’s sorrowful eyes looked into Rav Yosef’s eyes, and then he raised his voice in a wail, moaning, “Mashiach is still trapped.”

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 931)

Oops! We could not locate your form.