From the Depths

| November 30, 2021I feel a responsibility to share my story, recounting how my young campers saved my life

As told by Sholom Ross to Sandy Eller

I’m okay, I’m okay,” I said — and an unfamiliar voice responded, “No, you’re not”

I

had just finished davening at Chabad of the Five Towns in New York, where I lived, before Shavuos 2001, when fellow mispallel Dr. William Muller approached me.

“I have a summer job for you,” he said.

It was in Columbia, South Carolina, of all places. Dr. Muller explained that several frum families in the area — Chabad shluchim, one of whom is his son, and some other locals and visitors — needed someone to run a program in June between school and sleepaway camp.

“You’ll have your own car, your own apartment, and access to a private pool,” he said — all things that appeal to a 19-year-old.

To be honest, I thought Dr. Muller, whom I had known for years, was kidding. With my sense of geography, South Carolina may as well have been South America — and with a name like Columbia, I was sure they spoke Spanish there. When I realized he wasn’t joking, I told him I’d discuss it with my parents, but I had zero intention of going.

I mentioned the conversation to an older friend as we walked home from shul. He thought it could be a positive experience for me, and somehow, I had changed my mind by the time I walked through the front door.

“Ima, guess what — I’m going to South Carolina!”

After Shabbos, I spoke to Mrs. Muller, and within hours, the Mullers had booked my flight. A couple of weeks later, I was in Columbia and ready to roll.

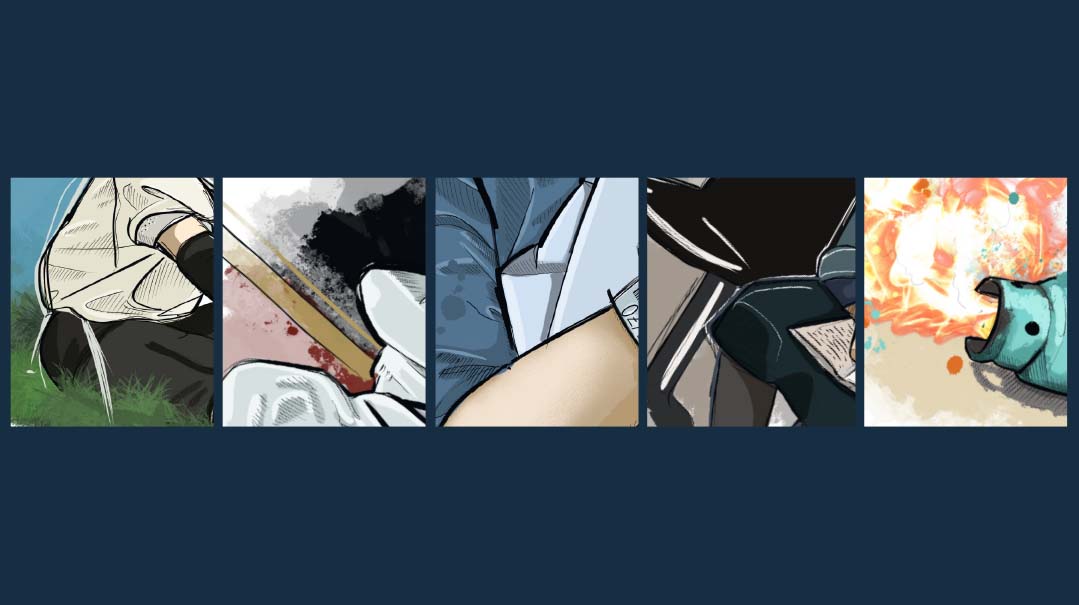

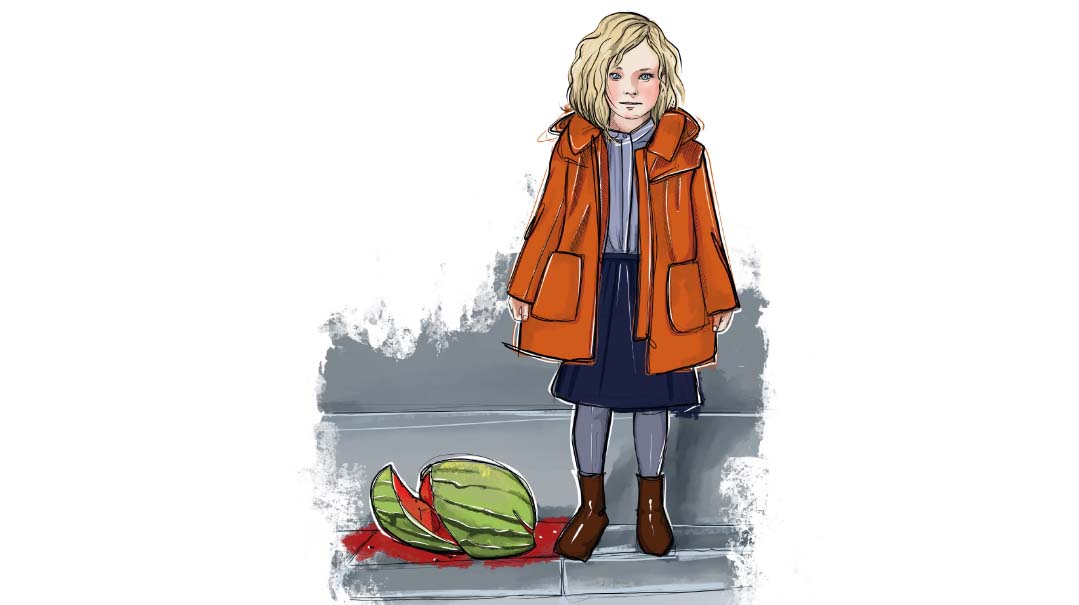

I had to entertain a total of six boys between the ages of eight and ten. The plan was relatively simple — start the morning with davening and learning, and then in the afternoon, play sports and maybe take them on a short trip, with some arts and crafts thrown in for good measure. The Mullers, like so many others in the neighborhood, had a large built-in pool, and these boys were like fish in the water. Me? I had learned the basics in camp ten years ago, but I don’t enjoy swimming, and while I had brought a bathing suit with me, I hadn’t actually planned to use it.

But the kids had other ideas. On Monday, our second day, they started calling, “Sholom, come in the water with us.” I didn’t have my bathing suit with me, so I had an easy out, but they insisted I bring it next time. They started in on me again the next day, and I finally agreed to join them. The kids were encouraging, and after a while, I even started enjoying myself. I realized that while I knew the strokes and could generally get from point A to point B, I didn’t have the breathing down pat, so I would hold my breath and keep going as long as I could before emerging to inhale and exhale when my head was above water.

At the end of the day, I went to the Coopers, where I stayed during the week. Mrs. Cooper, an ICU nurse, took one look at my sunburned face and read me the riot act, telling me point-blank that without sunscreen I couldn’t swim. Since I hate the smell and feel of the stuff, I was kind of relieved; it was a good excuse for staying out of the pool.

But the boys were relentless, and on Wednesday, I finally gave in, dutifully slathering on sunscreen before entering the pool.

“Let’s race!” one of the boys challenged me.

As we were getting ready to face off, two brothers who were always bickering got into yet another fight. I ordered one of them out of the pool. Surprisingly, he listened pretty quickly and went to sit on the side, legs dangling in the water. His brother joined us, and we got ready to race as the other boys splashed around in the shallow end.

“Ready, set, go!” we shouted, taking off from the deep end.

When I felt I couldn’t hold my breath any more, I stopped for some air.

And that’s when it happened. I had misjudged where I was — I thought I was already safely in the shallow end — but when I tried to stand, my feet didn’t touch the bottom. I didn’t know how to tread water, so I did the only thing I could think of — I put my head back under before coming up again for air. But I didn’t know how to breathe properly when swimming — that you’re supposed to exhale underwater and inhale when you come up for air. Trying to inhale underwater doesn’t work.

I was in serious trouble, and I knew it. My attempt to scream for help produced just the tiniest of sounds — I don’t know if anyone even heard me. Thankfully, the eight-year-old I had kicked out moments earlier saw what was going on. He jumped in and tried grabbing my freshly-sun screened arm, but it was slippery, and I slid out of his grasp.

“Help!” I heard him scream.

Maybe I can make it to the shallow end — it isn’t really so far away, I thought, and then suddenly, I wasn’t thinking anything at all.

I don’t know how long it took until I woke up at the side of the pool, surrounded by paramedics, but I later found out that an awful lot had happened in that time. Two of the boys ran into the house screaming for help while the others swam over to rescue me. By then, I had sunk to the bottom of the pool at the deep end. The boys managed to grab my body and maneuver it to the surface before gripping my limbs and swimming me to the shallow end, all while keeping my head above water. They swam me over to the steps of the pool, where the Mullers’ housekeeper Vicky, who had come outside when she heard the screams, did CPR on me repeatedly until the emergency crews arrived.

It was the paramedics who finally got me out of the pool. As I reentered the realm of consciousness, 30 minutes after I went under, I could feel the warmth of the ground beneath me. I wasn’t in any pain, but I was coughing, and somehow I knew the boys had helped me. I figured they were nervous about the whole situation.

“I’m okay, I’m okay,” I said — and an unfamiliar voice responded, “No, you’re not.”

I opened my eyes, and to my surprise, I saw emergency personnel everywhere, looking concerned. I was coughing, but I really did feel OK. (Granted, I was on oxygen at that point, but I wasn’t aware of that.)

“He needs to go to the hospital,” one of the EMTs said definitively to another.

“I don’t think I do,” I informed them. I still didn’t know what had transpired.

The EMTs asked the other adults there if they should take me, because I had essentially turned down care.

Later, I found out how close I’d come to losing my life.

“At one point, things looked so bad, two of the boys who are Kohanim actually ran out of the area,” I was told. “Blood was oozing out of your mouth and nose — they were afraid the worst was happening.” (A lifeguard later explained they weren’t wrong for making that assumption; that kind of bleeding is typically indicative of death.)

“You almost drowned,” the EMT said bluntly, once we were in the ambulance. “Do you know who did CPR on you?”

I did not.

“The housekeeper. You owe her your life,” he said harshly, like he was trying to impress upon me how serious the whole incident was.

At the hospital, the doctors attempted to remove the pool water from my lungs, which felt raw, like I was running in the cold. Every deep breath hurt.

My parents still didn’t know what had happened, so I called them. A go-with-the-flow kind of person, my mother took the news well, telling me she was glad to hear my voice. When I spoke to my father a while later, he joked, “Don’t drink any water — you already tried sucking up half the pool!”

I also called the boys and Vicky to thank them. But it didn’t really hit me — just how close I’d come to dying — until the doctor who first saw me in the ER poked his head into my room.

“People in your situation, if they aren’t dead, they’re vegetables for life,” he said, visibly moved. “You must really be connected Up There.”

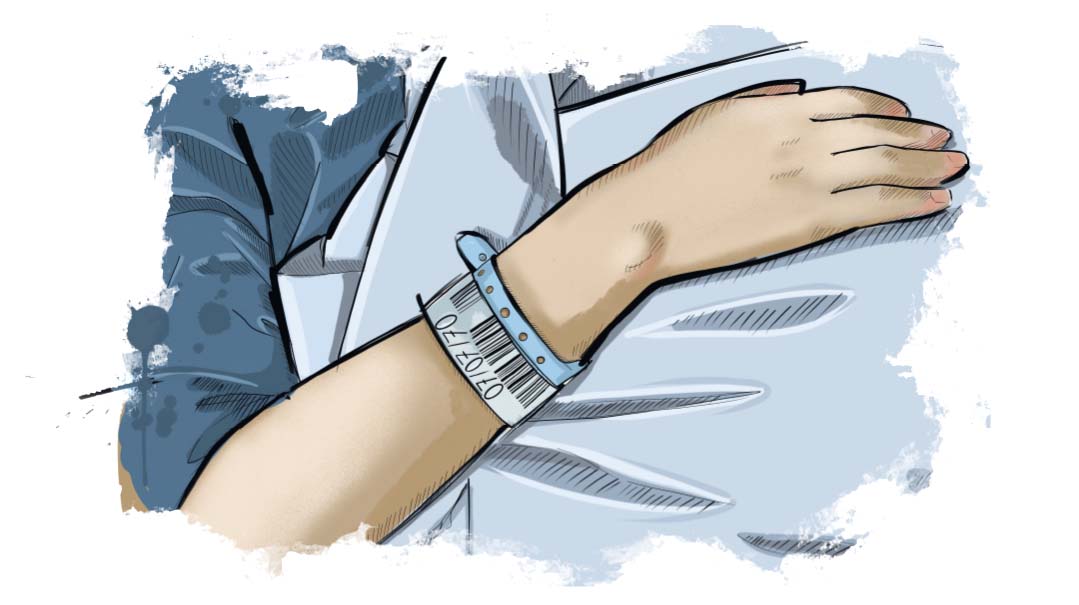

There was also the moment that defied logic. Not long after Chabad of South Carolina’s executive director Rabbi Hesh Epstein sent a fax with my name on it to the Lubavitcher Rebbe’s Ohel, a nurse came in with my hospital bracelet. For some reason, in the space where my name should have been was the word “Unknown,” and my birthday was incorrectly listed as 07/07/70. The number 770 is the address of Chabad headquarters in Brooklyn, New York, and has special significance; seeing it on my bracelet was like a brachah from the Rebbe.

On Friday, after spending two nights at the hospital for observation, I was released. I went to the Mullers’ house, where I would spend Shabbos, and sat with the family, reviewing what had happened. The boys apologized for banging my head on the steps as they tried pulling me out of the pool.

“Don’t worry, at that point, I couldn’t feel a thing!” I assured them.

There was a minyan in town the following Shabbos — a rare occurrence in Columbia — because the Epsteins were making a bar mitzvah for their son, so I bentshed gomel and davened Mussaf from the amud.

The next summer, the anniversary of my near-drowning, the 15th of Sivan, fell out on a Sunday. I flew to Columbia for Shabbos with bakery challahs and Chinese fare for a seudas hoda’ah. On Sunday, I went outside with the boys who had been there to look at the pool, which was empty for maintenance. You could see how dramatically the floor sloped down at the far end.

I made the brachah “she’asah li neis bamakom hazeh” as I looked at it in awe — How did a few kids manage to pull me out from the depths?

During the seudah, I quoted the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch about giving tzedakah on the anniversary of a miracle, and I gave Rabbi Epstein a check for Chabad of South Carolina.

Every Sivan since then, I host a different style seudas hoda’ah — I want to share my story with as many people as possible. I’ve hosted these seudos with my students in a Montreal yeshivah, with college-aged boys in my father-in-law’s basement, at kiddushim in different shuls, with families we’ve invited to our home, even on teleconferences and Zoom with people from the WhatsApp Tehillim groups I organize.

The 15th of Sivan is like another birthday, a shtickel Yom Tov. My father told me not to say Tachanun on that day, and while I don’t wear Shabbos clothing, I’m considering getting a new fruit so I can make a Shehecheyanu.

For me, the entire incident is a reminder that while Hashem performs miracles daily in the form of “nature,” once in a while, He pulls back the curtain, and we catch a glimpse of how He orchestrates our lives. It was the small things: that the brothers fought, prompting me to send one out of the pool, that he sat parallel to where I started having trouble breathing. Had he been anywhere else, he probably wouldn’t have noticed my struggles, with all the other boys racing and playing. That the boy who ran into the house shouting for help has asthma, which is why Vicky came running — she assumed he was in distress. and that Vicky knew CPR and was on the scene so quickly.

Having been blessed to live through one of these moments, I feel a responsibility to share my story, recounting how my young campers saved my life. Every breath of air that fills my lungs is clear proof that as much as we think we can control our own destiny, it is HaKadosh Baruch Hu Who runs the world.

Sholom Ross is the gabbai of Beth Joseph Lubavitch Toronto and the director of operations at Maxi Mind Learning, a neurodevelopmental program for children with learning disabilities in Canada. He lives in Toronto, Ontario.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 888)

Oops! We could not locate your form.