From Letting Go to Holding On

| February 20, 2024There’s no doubt; school has undergone a series of subtle transformations

“Don’t give any homework or any tests. No grades. Just show love and affection. And don’t ask girls why they haven’t come to school.”

It was the early stage of the war in Israel, and after the initial shell-shocked weeks, when all schools were closed, the school principal where I teach English was getting us teachers ready to go back.

“You can’t imagine what these girls are going through at home,” the principal continued. “They have fathers, brothers, and cousins fighting in the war, and besides that endless worry, they have to help much more at home.”

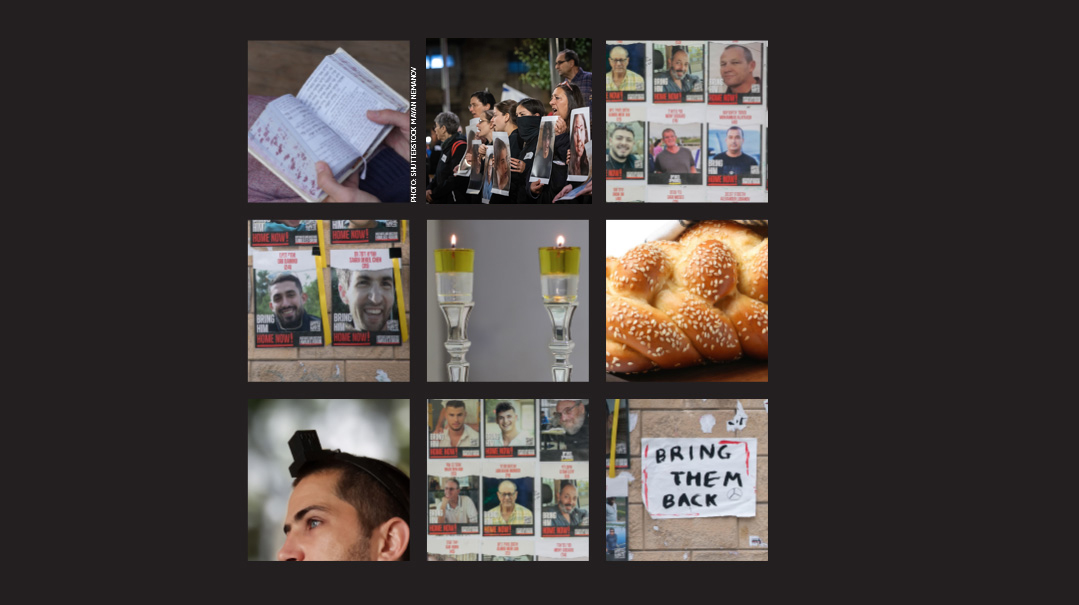

Four months later, I look at my lovely tenth grade students, and I wonder how much has actually changed. We’re still at war, and no one knows how long it will continue, if another front will open in the north. Most of their brothers are out of touch, and the hostages’ pictures are still framing the entrance to the mall.

Yet there’s no doubt; school has undergone a series of subtle transformations.

During Stage One after schools began again, absenteeism was rife. Some girls were afraid to go on buses in case there was an air raid siren, and they’d have to lie on the asphalt outside; some parents were too scared to send their daughters to school at all. Although our modern building is well equipped with safe rooms on every floor, no one relished the idea of rushing into one with crowds of panicky girls.

Just as challenging were the lives of the teachers whose husbands or sons were called up. They were supposed to carry on and concentrate on their classes when their minds were far away. “I told my pupils that functioning is really hard for me as well,” the history teacher announced as she dumped her bag on an empty chair in the staff room. “My son is in Gaza, but I made an effort and danced with my class.” She later brought her students to her house to pack up a tasty supper for teachers whose husbands were in Gaza or up north, leaving them alone at home with their children.

The gym teacher tried to inject some humor when she told us that her son, who had been in Gaza for two and half months straight, came home for a short visit. “He looked like Robinson Crusoe, a huge beard and hair like someone from the jungle, unrecognizable!” Then her face became more serious: “He’s home for two days. Imagine, I can breathe for two days. But he can’t even stay for Shabbos.”

One lunch break, I met the school counselor next to the staff room coffee machine, which, since the advent of the war, had been forced to produce an inordinate number of cups of coffee. She wanted to know how my students were doing, as the main aim at the time was to get girls back into the school framework so they could meet friends, and have some learning and volunteering opportunities to help them “preserve their sanity,” as she put it.

Thus Stage Two arrived. School activities indeed helped the girls rise above the situation. One day, the scent of freshly baked challos wafted into the staff room. The school had bought two electric ovens so that the girls could make challos and distribute them to wounded soldiers in Sheba Hospital. Another day saw the whole school transformed into a Luna Park with 200 evacuee kids coming out of their cramped hotel rooms to have a fun day. The next week, girls went off to pick crops for absent farmers.

And then, like a slowly moving river, reality set in: How long could we let go of our students, creating an environment of super consideration? Was putting no academic pressure on them the right way to handle the situation?

On the one hand, we could sympathize with the girl who was partially running the family boureka business, because there was no one else to do it. But what about the girls who had too much spare time at home? There were many who didn’t show up to school simply because staying in bed was a more comfortable and tempting option.

Arguments began among the staff. “They need us so they can hold on to something. A tight framework will be good for them. They should be distracted from the news by having to do assignments that keep their minds busy.”

“Who can demand work from teenagers who may be too worried to function? Surely they need a relaxed atmosphere and no pressure? How can they memorize English verbs at such a time? Don’t they have enough on their heads?”

The first warning sign that something needed to change was when one of my pupils actually asked for homework.

Could it be that the girls were thirsting for something to sink their teeth into?

We decided to start working on the annual English language research and writing assignment. My colleague suggested the topic be the war. I demurred, arguing that perhaps they wanted to get away from that. In the end, I gave a choice of topics to my class, and only one girl chose to write about a subject related to the security situation. “Can I write about my uncle who’s fighting in Gaza?” she asked.

“Well, yes, but it’s an ongoing situation. Won’t that make it complicated?”

“Never mind, I can ask him about what happened up till now.”

The next day she was back again. “I’ve changed my mind. Can I write about another uncle who was at the party in Re’im?”

There’s a silence. “You mean he survived?” I venture.

“Yes,” she says, her eyes alight. “And he’s willing to talk about it.”

Stage Three has come. We’re back to taking attendance religiously and implementing a strict behavior code for anyone who comes late. Homework and assignments are piling up, and girls are complaining they have too much to do. There are hardly any sirens anymore.

Girls are going for auditions for the school Purim play. There’s a steely fight for existence, an understanding that we must continue despite the stone that sits in our hearts.

And after my students write the names of the soldiers in their family on the classroom whiteboard, we daven together for Stage Four, when our nation’s pain will be but a memory.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 882)

Oops! We could not locate your form.