From Home of the Blues to Land of the Jews

| August 20, 2024“I would not exchange these seven weeks [learning in Chevron] for a lifetime of the wealthiest American millionaire”

Title: From Home of the Blues to Land of the Jews

Location: Chevron

Document: Nashville Banner

Time: August 27, 1929

I assure you I would not exchange these seven weeks [learning in Chevron] for a lifetime of the wealthiest American millionaire. A moment of spiritual life is not to be assessed in the most enormous terms of material wealth.

—Aharon Dovid (Dave) Shainberg

January 1929, Chevron.

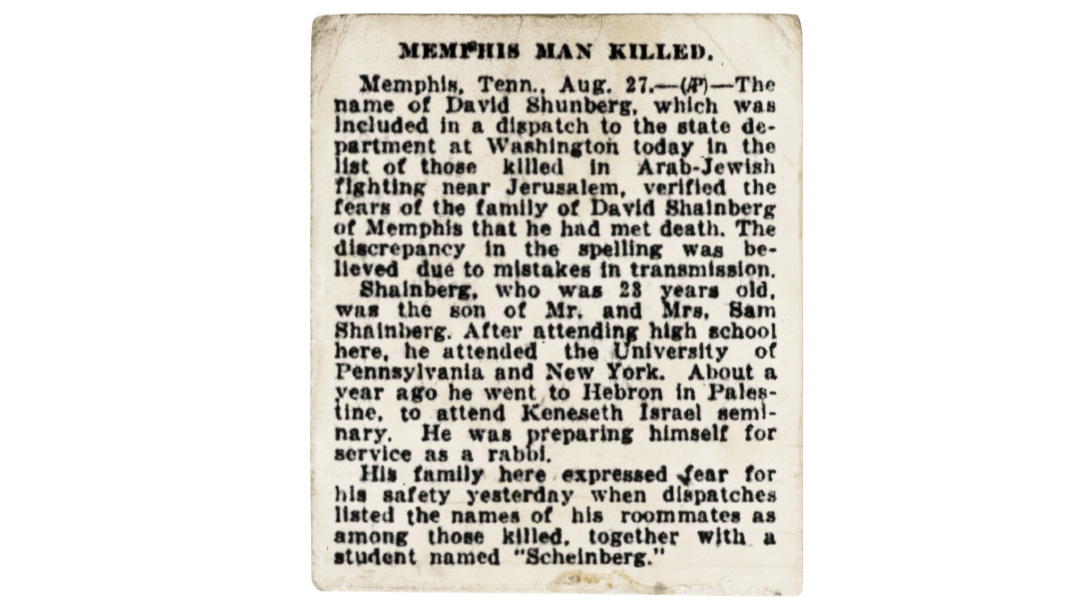

IN the annals of American Jewish history, certain stories shine with a particular poignancy that illuminates the depths of mesirus nefesh for Torah. The tale of Dave Shainberg, a young man from Memphis who journeyed to Chevron in 5688 (1928), is one such story — a narrative of spiritual yearning, sacrifice, and, ultimately, of a martyr whose life was cut tragically short.

Born in 1906 to Ukrainian Jewish immigrants Sam and Elizabeth Shainberg, Dave grew up in a family that epitomized the American dream. His father, who had arrived penniless in Memphis, built a thriving chain of dry goods stores. The Shainbergs were pillars of Baron Hirsch Synagogue, one of America’s oldest and largest Orthodox congregations. Like many immigrant families of the early 1900s, though, their Judaism was more cultural than deeply observant.

Young Dave’s path diverged dramatically from expectations. As a teenager, inspired by Rabbi Dr. Georges Bacarat of Baron Hirsch, he underwent a profound spiritual transformation. He wrote in his diary that he had found, “peace of mind and tranquility of soul.” This awakening led him to make difficult choices that baffled his family — refusing to work on Shabbos in his father’s store, and eventually dropping out of Wharton to devote himself to Torah study.

Dave’s journey from Memphis to Chevron was as much spiritual as physical. After graduating from Memphis Central High School in 5683 (1923), he enrolled in Wharton Business School at the University of Pennsylvania. He made close friends with other Jewish students and walked to shul on Shabbos. However, Dave returned to Memphis following his freshman year and was persuaded by Rabbi Bacarat not to return to Wharton.

For the next two years, Dave worked for his father by day and studied Torah at night. This period marked a significant turning point in his spiritual development. Rabbi Bacarat recognized in Dave a rare talent and the potential to become a great Jewish leader. He encouraged Dave to further his studies at the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS) in New York.

In 1927 Dave enrolled at New York University, taking classes in English literature, public speaking, and European history. Simultaneously, he devoted himself to intensive Torah study at RIETS, where he quickly gained a reputation as a masmid and insightful learner.

Despite his success in New York, Dave felt a pull toward something more. He yearned for a deeper connection to his roots, a life of simplicity in his people’s ancient homeland. As he wrote to his parents, “Our position is never secure in the land of our adoption. We are forever no more than strangers.” For Dave, only the Land of Israel could satiate his thirst for authentic Torah living.

On 27 Elul 5688 (September 12, 1928), against his parent’s wishes and with financial help from Rabbi Zev (Wolf) Gold, Dave boarded the RMS Aquitania in New York Harbor. His destination: the prestigious Chevron Yeshivah. The Statue of Liberty fading from view marked a stepping stone on Dave’s journey to his true spiritual home.

Dave’s letters home paint a vivid picture of his journey and first impressions of the Holy Land. “Eretz Yisrael exceeds my most fantastic visions and dreams,” he wrote upon arrival, adding, “My happiness now that I am at my destination knows no bounds.” In Chevron, he found everything he had yearned for: “Here, not only can I best acquire that knowledge which I seek, but I am in a thoroughly Jewish atmosphere and on holy ground.”

The 22-year-old Memphian swiftly acclimated to life in ancient Chevron among the luminaries of the Slabodka Yeshivah. Dave rented a room from Reb Betzalel Samarik, a venerable 72-year-old Torah scholar who had immigrated to Chevron from Russia. Reb Betzalel hailed from Zhetl, the birthplace of the Chofetz Chaim. Recognizing the unique opportunity before him, Dave arranged for Reb Betzalel to serve not only as his landlord but also as his personal mentor, engaging him in daily learning sessions. Under Reb Betzalel’s guidance, Dave made remarkable strides in his Torah studies, his progress a testament to both his own diligence and the rich learning environment of Chevron.

He marveled at the dedication and refined middos of his fellow talmidim, writing home, “The yeshivah itself is a revelation to me... In manners and deportment, they are perfect — the yeshivah is insistent upon a high standard of derech eretz within the yeshivah and outside as well.”

Dave’s spiritual growth in Chevron was rapid. “This week more than anytime thus far I have felt progress made in my learning,” he wrote. “So it is studying Gemara — you plug away constantly without denoting any increase of knowledge — feeling no perceptible change, then suddenly you perceive the change — the improvement. Something similar to a sudden ray of light entering a dark room.”

Yet even as Dave found his spiritual home, tensions were brewing in Eretz Yisrael. His letter, dated 14 Av 5689 (August 20, 1929), just four days before the massacre, described a tense Tishah B’Av in Jerusalem: “Yerushalayim has been in a state of constant excitement and tension for ten months now, and Tishah B’Av this tension reached almost the breaking point.”

Tragically, that would be the last letter Dave Shainberg would ever write home. On that terrible Shabbos morning of 18 Av 5689 (August 24, 1929), Shabbos Parshas Eikev, the Chevron massacre claimed 67 Jewish lives, including Dave and seven other American talmidim.

Author Yardena Schwartz describes David Shainberg’s final moments:

By 8:00 a.m. on “Black Shabbos,” the streets of Hebron were filled with some 3,000 Arab men from Hebron and neighboring villages, armed with swords, daggers, hatchets, butcher’s knives, iron bars, and wooden sticks. Rioters marched through the streets calling on Arab residents still inside their homes to join them. Many in the crowd waved their swords in the air, chanting, “Slaughter the Jews!” …

In the house of Rabbi Samarik, David [Shainberg] was doing what he must have believed was the only thing he could do as the sounds of slaughter flowed into the house from every direction. Together with the rabbi and his housemates, Benjamin Hurwitz and Tzvi Froiman, David prayed.… At first, the furniture David and his housemates propped up against the heavy front door kept the mob out, until they discovered that they could tear the shutters off the windows. Rioters dragged 73-year-old Rabbi Samarik outside, beating and stabbing him to death. Inside, David, Benjamin, and Tzvi tried to fight off their attackers. Outnumbered, they were overtaken with swords, knives, and clubs. Rabbi Samarik’s wife, Feige, was the only survivor. When the atrocities in Hebron were later denied by Arab leadership and the Arabic press, some of the bodies were exhumed as proof.…

The yeshivah students at the cemetery took one last look at their friend from Memphis. Only after his death did the leaders of the yeshivah divulge to the students that it was David who established and financed the yeshivah’s charity fund for the less fortunate students. Many of those who came from Europe were poor, and relied on the fund for tutors, clothing, and trips outside Hebron. In letters to Memphis, David often asked his father to send money for new suits and eyeglasses. Sometimes he didn’t even give a reason. As it turned out, he was donating much of what his father sent.

A False Sense of Security

When the Chevron-Slabodka Yeshivah first opened in 1925, it was welcomed with a grand ceremony attended by Chevron’s Jewish leaders, British officials, Arab dignitaries, including the city’s Arab governor. However, the yeshivah’s early days were not without challenges. As Dave related in a letter to his mother, “There occurred not a little trouble from the Arabs here. Stones were thrown into the yeshivah buildings; students were attacked on the streets.” Yet a remarkable turnaround occurred following a pivotal incident.

When a young Arab vandalized the home of Rosh Yeshivah Rav Moshe Mordechai Epstein, causing damage and injuring family members, the rosh yeshivah surprised everyone by pleading for the culprit’s release in court. Dave wrote, “Ever since then there has been no trouble whatsoever. To the contrary, now the Arabs treat the yeshivah students with utmost respect and courtesy.”

This apparent transformation, coupled with centuries of almost exclusively peaceful coexistence in Chevron, lulled its residents into a false sense of safety. The talmidim, ensconced in their world of Torah study, remained largely oblivious to the gathering storm around them. Despite growing tensions across the land, they felt secure in a city they believed exemplified harmonious relations between Jews and Arabs, unaware of the tragedy that would soon befall them.

From Marseilles to Memphis

Rabbi Dr. Georges Bacarat, a dynamic figure in early 20th-century American Jewish life, left an indelible mark on both religious and secular spheres. Born in Marseilles, France, Bacarat arrived in New York in 1911 to work in the insurance industry, but his true calling lay in Jewish education. His scholarly acumen led him to teach at universities and Jewish institutions alike, including a position on the original faculty of New York City’s Talmudical Academy (later MTA) in 1917.

As a founder of the Jewish Academians Society of America in 1916, he worked alongside renowned Orthodox intellectuals to advance Jewish causes in academia. In the course of his rabbinic career, Bacarat led Orthodox communities in Portsmouth, Virginia, and Memphis, Tennessee, where he profoundly influenced young Dave Shainberg. In his later years, while serving as chief interpreter for the New York Supreme Court, Bacarat continued his rabbinical work at the Jewish Community House of Bensonhurst, introducing countless young Jews to Torah study. His passing in 1943 at 60 cut short a remarkable life dedicated to the Jewish People.

The forthcoming book Ghosts of a Holy War: The 1929 Massacre in Palestine That Ignited the Arab-Israeli Conflict (Union Square and Co.) offers readers a compelling glimpse into the spiritual odyssey that led 22-year-old Dave Shainberg to Chevron. Award-winning journalist and author Yardena Schwartz skillfully uses this poignant narrative as a lens to examine the broader historical context. Through Shainberg’s story, Schwartz illuminates the origins of the conflict that has plagued Israel since its inception, tracing its roots to events that transpired long before the establishment of the Jewish state. Her work demonstrates how the seeds of the ongoing struggle, most recently manifested in the war Israel has been fighting since October 7, were sown in the tumultuous period of pre-state Palestine. Ghosts of a Holy War will be released on October 1 and is now available for preorder on Amazon.com.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1025)

Oops! We could not locate your form.