From Boca to Bushtyno — My Journey Home

| October 28, 2025A dusty sefer in a Boca genizah connected me to ancestors in a way I’d never imagined

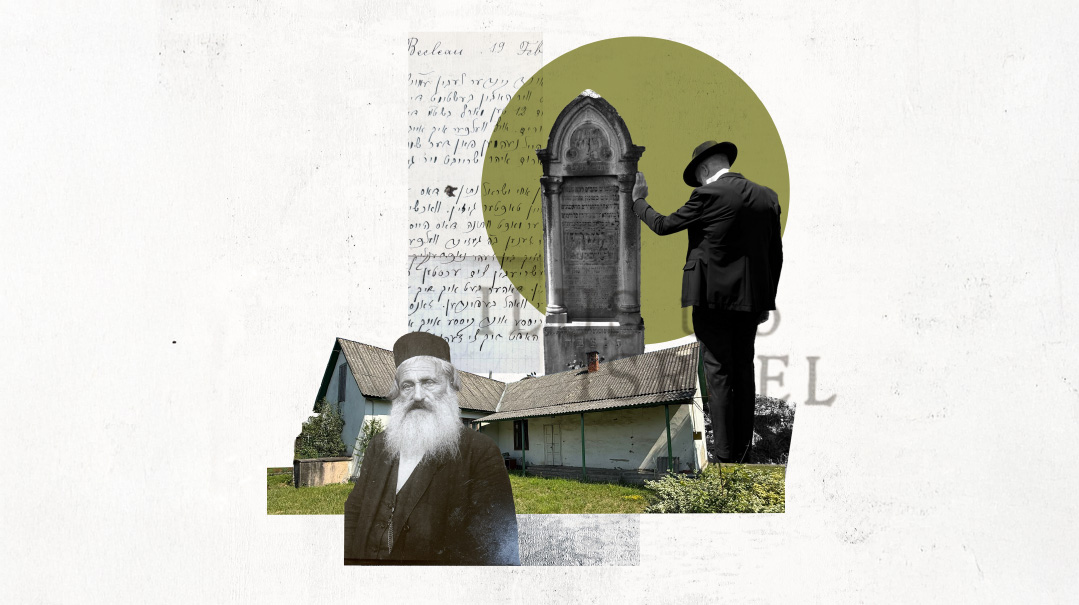

From a dusty stack of yellowed letters that somehow found their way into a Boca Raton genizah, I was able to connect with my ancestors in a way I’d never imagined. Who would have known that my great-great-grandfather was the confidant of Rebbe Mordchele of Nadvorna?

L

ast summer, for the first time, I fulfilled a long-held dream to visit my grandparents’ hometown in Europe. By the time the plane touched down in Budapest, I felt like I was carrying generations on my back.

My grandparents, both Holocaust survivors, had long since passed away, but their stories were etched onto my soul. I knew that they’d had happy childhoods surrounded by loving grandparents, siblings, and cousins. I knew that they were first cousins who married after the war, after each had lost their first spouse and children.

But there was so much that was hidden, too painful to share. And I was desperate to learn more, to fill in some of the missing gaps.

For years, I had dreamed of visiting their hometown of Bushtyno. I had always imagined standing where they once stood, breathing in the same air, walking those same cobblestone streets.

But life gets in the way; children, community, responsibility. The timing was never right.

Until now.

This past summer, my husband and I found ourselves in a new stage of life: temporary empty nesters. Our children were either married or away at camp, and for the first time in decades, the horizon stretched wide open. That’s when our friend Josh reached out. Again.

Josh, a self-declared kevarim enthusiast, had been trying for years to convince us to join him on one of his whirlwind cemetery tours across Europe. Now, hoping to finally find the answers I sought, we accepted his invitation.

“We’ll join him,” I told my husband, “But we have to stop in Bushtyno.”

As it turned out, Bushtyno, Ukraine, wasn’t just my grandparents’ hometown — it was also the resting place of the great tzaddik Rav Mordechai of Nadvorna. His kever was already one of the stops on Josh’s itinerary. Hashem was clearly orchestrating something.

We mapped it all out: We’d start in Budapest, at the kever of Rav Shimon Oppenheim in Óbuda, then head northeast through the Hungarian countryside, visiting the burial sites of tzaddikim along the way — the Liska Rav, the Kaliver Rebbe, the Yismach Moshe in Újhely, the Komarna Rav and more. The following day we would cross the Ukrainian border to Bushtyno, Munkacs, Chust, and return to Hungary to visit Reb Shayele in Kerestir. We’d also stop in Mád, another town with Jewish roots, and then head back to Budapest. It was going to be a trip of memory and meaning.

I prepared for the trip extensively. I was determined to find out more about my ancestors before stepping foot on European soil. I needed names, addresses, dates, details — something more than just gravestones and faded memories.

Down the Rabbit Hole

One week before our flight, I dove headfirst into research. I started with books and phone calls to historians and genealogists. And then I discovered Ancestry, a digital genealogy platform.

What began as curiosity quickly spiraled into obsession. I found marriage certificates, immigration papers, even registration cards from concentration camps. I saw names I’d never heard mentioned — cousins, aunts, children, and spouses lost to war. Night after night, I stayed up too late, transfixed by digital ghosts.

Then one night, something strange happened.

I spotted a familiar name on my family tree. But it wasn’t a family member. It was Simon, a long-standing member of our shul, Boca Raton Synagogue. We had no familial ties to each other — at least, none I knew of.

I called my husband over. “Why would Simon be on my Ancestry page?”

He had no idea but was certainly intrigued. “I’ll ask him,” he said.

The next day, my husband reached out to Simon.

“Were you researching my wife’s family on Ancestry?” he queried.

Simon was puzzled. “No… I mean, I do like genealogy, and I’ve looked into my own family, but I don’t go digging into other people’s families for fun!”

“But your name showed up on her tree,” my husband said.

“That’s strange. What’s her maiden name?” he asked.

When my husband told him, Simon’s face changed.

“I’ve been looking for that family for years,” he whispered.

Ten years ago, Simon had taken some old seforim from the shul’s sheimos pile. He has a hobby of collecting ancient artifacts, and that day he hit the jackpot. Inside one of the books, tucked between yellowed pages, he found a stack of letters and postcards — frayed, delicate, and dated from the 1920s through the 1940s. He’d held onto them, unsure of what to do.

“I knew they had to matter to someone,” he said.

Recently, he’d used Ancestry to trace the family of the letter writers. He inputted names into a family tree, made some progress, even tried contacting someone in Spain. No response.

Then my husband told him my family name, Bruckstein/Rath, and suddenly, after a decade, his quest to return the letters had ended.

Voices from the Past

Simon brought the letters over that very day, and I trembled as I opened the stack. The first letter, written in Yiddish script, was signed by Moshe Bruckstein — my great-great-grandfather — writing from Bushtyno in 1929, to his daughter who had moved to America.

He begged her to stay religious. He updated her on her siblings and the difficult conditions in their town.

The paper was so delicate, but his voice came through strong and urgent.

There were letters and postcards from my namesake Yocheved Rath, my great-grandmother, and most shockingly, a wedding invitation for my grandfather’s first wedding in 1935. We had known he’d been married before the war, but the details had been lost, too painful to pass down.

Now I had his first wife’s name. The date. The city: Beclean, Romania. A letter from my great-grandmother inviting her sister in New York to the simchah.

Suddenly, my family’s story of loss and survival became real. Tangible.

Right then, I decided that I would bring Moshe Bruckstein’s letter with me to Bushtyno. I would return it to the place it was written. I would daven at his kever with his words in my hand.

Return to Bushtyno

Armed with the letters, my grandmother’s worn Tehillim, and a beautiful packet my husband compiled with bios and divrei Torah from every tzaddik on our itinerary, we flew to Budapest and hit the ground running.

Day one was powerful. Graves, Torah, history. But it was day two — Bushtyno — that made my heart pound.

Crossing the Ukrainian border, soldiers checked our passports. There was no sign of war where we were, but we felt tense nevertheless.

And then we arrived.

I stepped out of the van and took a deep breath.

I was in Bushtyno.

We started at the cemetery. It was quiet but for a construction team setting up a tent — an influx of chassidim were expected soon for the Nine Days.

We entered the ohel of Rav Mordechai of Nadvorna, learned his Torah, davened. Then we searched for my family.

There they were — buried right beside the Rebbe.

My great-great-grandfather Moshe Bruckstein, his wife Sirka, my great-grandmother Malka Tiltza, and others. Moshe had been close to Rav Mordchele, had been his trusted confidant and main supporter. He had lived directly across the street from the tzaddik and witnessed firsthand his greatness and brilliance.

That closeness shaped the course of his life.

Moshe Bruckstein had grown up steeped in chassidic lineage: His father, Rav Yisrael Nosson Alter, was the Rebbe of Pistin and author of Minchas Yisrael and Emunas Yisrael; his grandfather, Rav Chaim Yosef, was a close chassid of the Baal Shem Tov and friend of the Alter Rebbe, the Baal HaTanya. The family were cousins to the Teitelbaums of the Satmar dynasty.

Moshe had a modest lumber business near the forest. One Shabbos, his wife had the honor of sending a kugel to the Nadvorna Rebbe’s Friday night tish. But by the time the tray reached Moshe, only crumbs remained. The Rebbe, noticing his disappointment, smiled and said, “From the shards of the broken Luchos, Moshe Rabbeinu became wealthy.”

Moshe didn’t understand then, but a few days later, while walking through the local forest, he realized that the scraps of wood discarded by lumberyards could be crafted into canes. Soon he started his own business creating fancy umbrella handles and fashionable walking sticks, sought after by Europe’s elite. He opened a factory and became one of the largest distributors across the continent, later selling hundreds of thousands of canes and crutches after World War I. The Rebbe’s blessing had come true: From the scraps, Moshe Bruckstein became a wealthy man.

From that point on his devotion to the Rebbe only grew, and he served as his right hand on many tzedakah and chesed initiatives. When he died, he was buried in the tzaddik’s tallis.

Now, nearly a century later, in the Bushtyno cemetery, I placed his handwritten letter on his kever. I lit a yahrtzeit candle and cried, overwhelmed by the privilege of returning his words to their origin.

At my great-grandmother’s kever, I davened from my beloved grandmother’s Tehillim, the one she used to pour out her heart to Hashem, a practice she learned from her mother. My great-grandmother Malka Tiltza (Yarmush) Bruckstein, who passed away right before the Jews of Bushtyno were deported, raised a special daughter — a woman of resilience, faith, and strength. I made sure to tell her that day.

A House, a Picture, a Miracle

After our visit to the cemetery, I had one more place I hoped to see.

I pulled out a faded photo from a 1990s visit to Bushtyno depicting my grandmother and her sister and brother-in-law standing in front of a house. “Their family home,” I’d been told.

We drove aimlessly, then walked around the streets, showing passersby the photo. No luck. Finally, in desperation, I uploaded the picture to ChatGPT and asked, half jokingly: Can you find this house in Bushtyno?

The reply was: We can’t, but try the town hall, with an accompanying address.

So we headed to the town hall, which turned out to be a drab, tiny building. The mayor and deputy mayor were sitting around in what felt more like a living room than a government office. The deputy mayor spoke a halting English, and we explained what we were looking for. He showed one of the female staff members, a longtime Bushtyno resident, the photo.

She gasped.

“I know this house!”

It was just down the street from the town hall. She and the deputy mayor walked us there. The house had been a night school in the ’90s. Now it now belonged to a local church.

We turned the corner — and I froze. It was the house.

Same windows. Same sloping roof. Same backdrop.

My grandmother and her family had spent time in this home. As we opened the gate, walked the perimeter, explored the backyard, looked in the windows and stood at the front door, I felt a tremendous connection to her, picturing the people, experiences and conversations that happened there.

Alpine Encounter

After leaving Bushtyno, we visited Munkacs, Chust, and Mád — towns that once boasted a vibrant Jewish life and were now eerily quiet.

Our visit to Budapest was a different story — modern, alive, yet tinged with memory and my personal family history. We walked the Chain Bridge, where my great-uncle had been arrested for cheering as it was bombed. We stood at the Shoes on the Danube memorial and thought of a cousin who was murdered there.

And then we started the relaxing, quiet portion of our summer, in the fresh mountain air of Switzerland.

One sunny day, we hiked in Davos, along with what felt like the entire chassidish world. Standing in line for a gondola, we realized we were missing a ticket. A woman nearby offered to help. She spoke some English, and we started chatting.

“Where are you from?” I asked.

“Bnei Brak,” she said. Out of curiosity, I asked her, “What type of chassidim are you?”

Imagine my surprise when she said, “You probably haven’t heard of it, my husband’s a Nadvorna chassid.”

I smiled. “We just came from Bushtyno. My great-great-grandfather Moshe Bruckstein was very close with Rav Mordchele. He’s buried right beside him.”

Her jaw dropped.

“My husband is Rav Mordchele’s great-grandson. His brother is the current Nadvorna Rebbe of Bnei Brak. He’s leaving for Bushtyno next week.”

My husband proceeded to fill him in on what we had discovered in preparing for this trip and showed him the seforim that had stories showing the close connection between our two families. Our new Nadvorna friend was delighted to hear all about it.

We stood there, embracing the moment, two descendants of Bushtyno, united on a mountain in Switzerland.

This trip was never just a vacation. It was a journey of discovery. Not just to cities or cemeteries, but to pieces of my soul that had been waiting to be found. The connection I always had with my grandparents only deepened from this experience.

Hashem guided every step — from a dusty sefer in a Boca Raton genizah, to the precious letters in my hand, to the house down the street in Bushtyno, to the stranger in Davos who turned out to be mishpachah.

He planned it all.

All I had to do was go along for the ride.

Author’s note:

If you have any information about how those letters may have ended up in genizah in south Florida; any family ties or connections to Bushtyno or Beclean, Romania; or any insights into this article, please contact me through Mishpacha.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1084)

Oops! We could not locate your form.