From Assimilation to Assassination

| July 9, 2024Walther Rathenau grew up with aspirations of assimilation for German Jewry

Title: From Assimilation to Assassination

Location: Berlin, Germany

Document: The New York Times

Time: June 1922

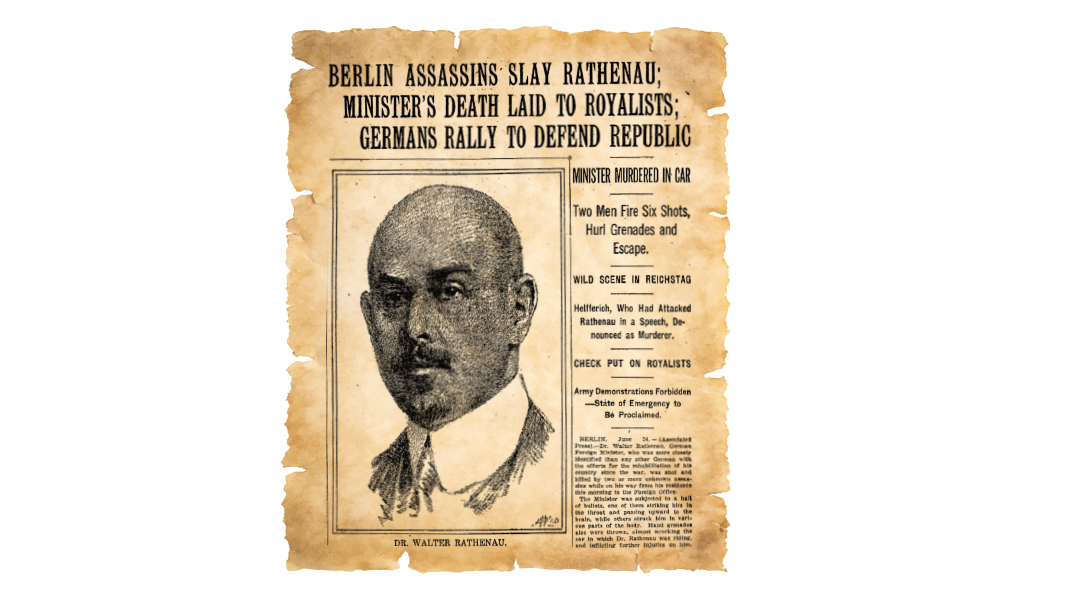

One June 24, 1922, at about eleven in the morning, [Walther] Rathenau — still firm in his refusal to accept a bodyguard — left his villa in Berlin and drove to the Foreign Ministry.…

At a turn of the wide Koenigsallee, his car was overtaken by an open vehicle. Several shots from automatic pistols were fired. Rathenau was hit in the chin and spinal cord and died before a doctor arrived.

Public agitation against Rathenau had increased since he had become foreign minister in February. The venerated General Erich Ludendorff, who was back in Germany after fleeing during the revolution and was active in extreme right-wing splinter groups, had sealed Rathenau’s fate by insinuating that “the Jewish prince” had sabotaged the war effort. The nationalist-conservative deputy Karl Helfferich had joined the attack on him in the Reichstag while, outside, rioters yelled in chorus: “Kill off Walther Rathenau, the greedy Jewish sow!”…

Though one of the conspirators, Erich von Salomon, later claimed the target had not been a Jew but rather a representative of the hated republic, the symbolic aspect was not limited to an attack on the republic; the assassination symbolized the crisis of assimilation.

—Amos Elon, The Pity of It All

Born into a wealthy secular Jewish family in Berlin, Walther Rathenau grew up with aspirations of assimilation for German Jewry. Walther served on the board of his father’s company, AEG — Germany’s largest producer of electricity and electrical equipment — and was an investor in or board member of more than 80 corporations.

The late 19th century offered great opportunity for German Jewry, but also saw a rise in anti-Semitism. Rathenau grappled with his own Jewish identity, and publicly called for assimilation as a solution for acceptance by German society. Rathenau had been humiliated when served in an elite regiment in the Prussian military and was denied an officer’s commission due to his Jewish identity.

He remarked, “For every German Jew, there is a painful moment he remembers his entire life: the moment he is first made fully conscious that he was born a second-class citizen. No ability and no achievement can free him from this.”

In 1897, when he was 30 years old, he penned a bizarre article in Die Zukunft, Berlin’s most popular political magazine, titled “Hear O Israel!” He proclaimed, “I wish to confess at the outset that I am a Jew,” before encouraging German Jews to have a more pleasant physical countenance. “Once you recognize the unshapely form of your bodies, the raised shoulders, the clumsy feet, the soft roundness of your forms, as signs of bodily decline, you will be able to start working for a couple of generations on your bodily rebirth.”

He asked German Jews “to look in the mirror, re-educate themselves, and leave the ghettos to breathe German mountain and forest air. Jews must consciously adopt the tribal qualities of the host country, the behavioral patterns of the racially superior, tough, militarily bred Prussian aristocracy. The host people might then be more likely to recognize Jews as just another German tribe.”

German Jews were outraged at this preposterous vision for assimilation and acceptance. Rathenau himself regretted publishing it, but the damage was done. German anti-Semites approvingly cited this article for decades.

The Weimar Republic arose in the chaos following Germany’s defeat in World War I and the Treaty of Versailles, which held Germany responsible for the war. Rathenau served in leading roles in the government from its inception. In February 1922, he was appointed foreign minister.

Amos Elon describes his impossible task:

As foreign minister, he worked hard to reconcile Germany with its former enemies, but his policy of strict compliance with the terms of the unpopular Treaty of Versailles infuriated the nationalist right.…

The [right-wing terrorist] militia declared Rathenau public enemy number one. The police urged Rathenau to accept bodyguards. Rathenau refused — the very suggestion offended him. Zionist leader Kurt Blumenfeld and [Albert] Einstein visited Rathenau one evening at his palatial home.

A Jew should not run the foreign affairs of another people, Blumenfeld said. “You see only yourself. You don’t realize that every Jew will be held accountable for your actions — and not only in Germany. You have no right to do this!”

“Why not?” Rathenau responded. “I am the best man for the job. I am fulfilling my duty to the German people by offering my services. We must break down the barriers the anti-Semites have erected to isolate us.”

Rathenau’s funeral after his assassination in June 1922 embodied the paradox of his entire life. It was the largest Germany had ever seen, as two million citizens lined the streets in the rain. The ceremony commenced with strains of Wagner’s Siegfried’s Funeral March, and continued from the Reichstag to the Jewish cemetery, where he received a Jewish burial.

Identity Crisis

Rabbi Nachum Aaronson from Manchester, England, shared a story that is printed in Hagaddah Seridei Eish:

Shortly following World War I, Rav Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg witnessed a spectacle that occurred at a Berlin shul during Yizkor on Yom Kippur. A limousine arrived at the shul, and Walther Rathenau entered to recite Yizkor for his father, exiting immediately thereafter. His brief visit angered the congregants, who found his actions disrespectful. Rav Weinberg addressed the criticism, referencing Yaakov Avinu’s return to Mount Moriah to pray where his forefathers had, emphasizing the importance of connecting prayers to one’s ancestors. He defended Rathenau’s brief prayer as a sincere act of honoring his father.

Years later, Rav Abba Weingort recounted this story during a lecture in Israel.

A young man in the audience revealed himself as Rathenau’s nephew. “I am the grandson of Emil Rathenau! My mother [Edith Andrea] was Walter Rathenau’s sister.”

He had grown up irreligious, but eventually became a baal teshuvah. Rabbi Weingort posited that Emil Rathenau’s merit from his son’s recitation of Yizkor may have influenced his grandson’s return to faith.

Baal Teshuvah?

Following Rathenau’s assassination, his mother Mathilde penned a letter to the mother of Ernst Werner Techow, one of the assassins:

In grief unspeakable, I give you my hand. You, of all women, the most pitiable. Say to your son that in the name and spirit of him who was murdered, I forgive, even as G-d may forgive, if before an earthly judge he makes a full and frank confession of his guilt, and before a heavenly one repent. Had he known my son, the noblest man earth bore, he had rather turn the weapon on himself than on him. May these words give peace to your soul.

A legend developed that as a result of this letter, Techow regretted his actions, and even saved Jews in Marseilles, France, during the Holocaust, when he served in the French Foreign Legion. The only issue with the story is that it’s completely unfounded, as Techow served in the German Navy, and, as far as is known, never saved any Jews.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1019)

Oops! We could not locate your form.