Fragments from Fustat

Scraps of parchment and ink testify to the Rambam's towering impact

Photos: Jeff Zorabedian, David Khabinsky/Yeshiva University

How to capture the essence of the Rambam? Follow the paper trail preserved in the Cairo Genizah and elsewhere, plus manuscripts, fragments and letters that occasionally surface in auction houses and at antique dealers. Chicago businessman Robert Hartman is one such collector, and together with historian Dr. David Sclar, he’s made the priceless artifacts accessible to everyone

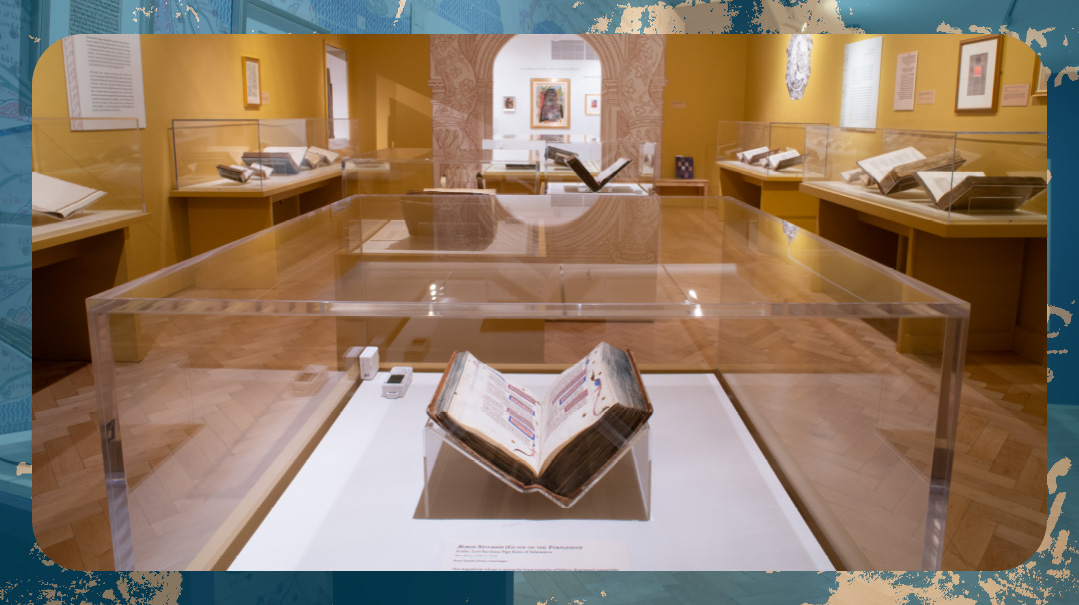

The world of antiques, manuscripts, and ephemera (including the very term “ephemera”) is generally reserved for scholars and collectors; the average layman doesn’t necessarily relate. An exhibit currently running at the Yeshiva University Museum, however, seems to be the rare exception to this rule. The Golden Path: Maimonides Across Eight Centuries, which has been running since the middle of last year and is slated to remain on display until this Thursday, is particularly unique in its wide range of appeal. And we want to give readers a glimpse before all the artifacts go back to their owners.

Rabbeinu Moshe ben Maimon, known as the Rambam or Maimonides, was one of the most impactful Jews in all of history. The scope of his work is breathtaking. He was the great posek, the codifier of Torah law via his magnum opus, the Mishneh Torah. He was the great philosopher whose monumental work, the Moreh Nevuchim (Guide to the Perplexed), has illuminated the path of rational belief for multitudes, both Jew and non-Jew alike. He was the great ethicist, whose Shemoneh Perakim and Hakdamah L’Cheilek describe proper behavior as well as correct beliefs. He was the great expositor, whose Pirush HaMishnah was the first full-length commentary ever written on the entire Mishnah.

He was the great leader of his generation — a beacon of light for the Jewish community, guiding communal affairs in his hometown of Cairo and as far away as Yemen. He was a teacher to the scholarly and educated, and he was a teacher to the simple Jew struggling to serve Hashem on the most elementary level. He was an advocate, a spokesperson, a fountain of wisdom, and so much more. And aside from all that, he was a preeminent astronomer and physician who authored seven works related to medicine.

In the eight centuries since he lived, his influence has only grown, as his writings and teachings have been the focal point of so many lives spanning many continents and eras.

How does one capture the essence of such a larger-than-life figure?

In contrast to most Rishonim, whose original writings and artifacts were destroyed by persecution and oppression, there is a significant trail of first and secondhand kisvei yad of the Rambam, in addition to many artifacts, that have been preserved in the Cairo Genizah and elsewhere. These open a window through which we may explore his world. Fragments and letters traced back to the Rambam occasionally surface in auction houses and at antique dealers, creating a small niche in the market of Judaica for “Rambam collectors.”

Robert Hartman, a businessman from Chicago, is one such individual. Several decades ago he purchased his first Rambam manuscript, and his collection, driven by his deep-seated connection and appreciation for the Rambam, has grown ever since. Several years ago, he hired Dr. David Sclar, a scholar of history and a librarian, to catalog all of the items in his collection and provide the background information and pertinent history of each.

Dr. Sclar was so taken by this collection that he suggested to Mr. Hartman to allow the material to be exhibited to the public. Mr. Hartman generously agreed and the exhibit — which showcases many items of the Hartman collection, along with a number of other pieces on loan from various collections — was formed.

Final day for exhibition tours is Sunday, March 3:

Dr. David Sclar (left) was thrilled to be able to showcase the collection to the public. So were Rabbi Neuberger and Yehuda Esral

Curator’s Connection

The large flow of visitors to the exhibit has realized Dr. Sclar’s vision; he hoped it would bring in all sorts of people. “Throughout Jewish history, there is literally no one else who is as meaningful to such a wide spectrum of people,” Dr. Sclar says.

In addition to the actual exhibit, Dr. Sclar produced a 250-page catalogue with extensive background information on each exhibit item, along with a dozen essays by prominent academics on various aspects of the Rambam’s legacy.

In the year since the exhibit opened its doors, many visitors have made their way through, from Modern Orthodox to Satmar chassidim, not to mention Christians and Muslims and everyone in between. A Muslim Imam from Southeast Asia came in an effort to promote the importance of Jewish tradition and culture to his Muslim brethren. High school classes have visited, and prominent university professors have brought their students. A feature on the popular Seforimchatter podcast inspired a flow of Lakewood-based visitors, among others.

The visitors’ levels of familiarity with the Rambam is varied; to some, the extent of their knowledge is the Maimonides Medical Center, while others are seasoned professors and scholars.

But the common denominator is that they all feel some sense of connection with the Rambam, and as such, have become a part of the story of his ongoing impact.

When Dr. Sclar leads a tour, rather than lecture, he’ll invite comments and observations from visitors. As a result, despite his immense familiarity with the exhibit, he found himself learning a lot. For example, the Cairo Genizah, which contained 800 years of documents and manuscripts, is not as much of an anomaly as most Ashkenazic Jews seem to think — one visitor told him about a similar “genizah” in Uzbekistan which houses centuries of old papers. In fact, the concept of these attic-like genizahs is part of Muslim culture.

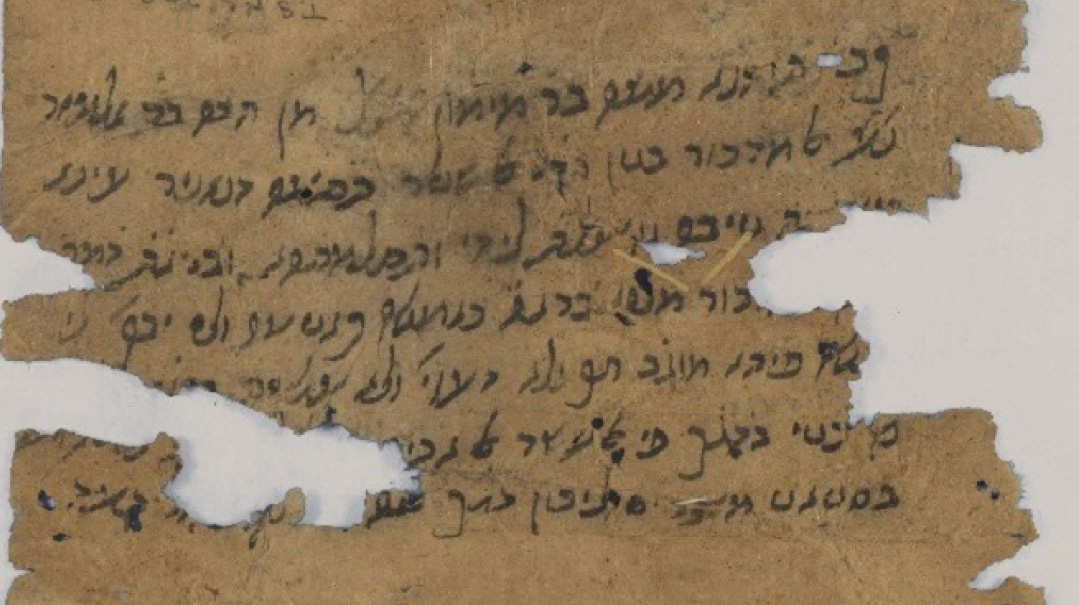

This past summer, the Museum had to give back two items of great intrigue to the Bodleian Library which had loaned it to them: a Mishneh Torah signed off by the Rambam, and a manuscript of Pirush HaMishnah with emendations in the Rambam’s handwriting. Left with some gaps in the display, Dr. Sclar sought to fill their place with some new items. By chance, he happened to select a letter in the Rambam’s handwriting making an appeal for pidyon shevuyim — a choice which would prove to be unfortunately meaningful not long after.

Perhaps what Dr. Sclar gained most from the exhibit was witnessing the ongoing influence of the Rambam, as his writings and teachings continue to inspire the many visitors who came to learn more about this towering personality.

The Process Unfolds

The exhibit has hosted many people of all stripes, each finding their own way to connect with the larger-than-life persona of the Rambam.

The traditional beis medrash student, for example, relates to the Rambam primarily through his Mishneh Torah, whose organization and succinct halachic summaries of virtually every sugya in the Talmud has generated vast rabbinic literature, with literally hundreds of commentaries analyzing and dissecting its every word. This budding Talmudic scholar will be left inspired to continue this tradition after viewing a fragment of the original text in Rambam’s handwriting from the late 12th century, where the margins are filled with the Rambam’s emendations and corrections. Words are crossed out and replaced with others, showing Rambam’s process in developing his massive work. Rambam is no longer a vague historical character, but an actual person working and toiling at understanding the entirety of Torah, and creating the work that merited the intense scrutiny of talmidei chachamim for generations.

In a similar vein, a minor but significant item featured in the exhibit is on loan from the Cambridge University Library. The single document is the Rambam’s glossary of words in Judeo-Arabic comparing certain terms to other synonyms, in an apparent attempt to choose the most appropriate words to use.

A letter apealing to the community to take part in pidyon shevuyim

Leader on the Front Lines

Rambam’s role as a dedicated leader to his people is evident via many of his letters. A particularly poignant item in the exhibit — sadly very relevant to today’s time — is a letter signed by the Rambam, appealing to the community to take part in the important mitzvah of pidyon shevuyim. Other documents show donor receipts, accounting for the money that had been raised for the cause. Far from being a scholar who was engrossed only in his learning, he descended from his high place to tend to the needs of his people.

The Rambam’s devotion to the public can be seen by the evidence of his general availability. When Shmuel ibn Tibbon endeavored to translate the Moreh Nevuchim from its original Judeo Arabic into Hebrew, he wrote to the Rambam with various questions, and requested permission to make the trip from France to come spend time with the Rambam in his hometown of Fustat, the capital of Egypt at the time.

Rambam wrote back to him in a well-known letter:

“If you wish to confer with me on matters of wisdom, do not hope for even a single hour either during the day or the night…. Every day I head to Cairo early in the morning. Even if there is no impediment, or if nothing unusual happens I return only in the afternoon… I treat my patients until nightfall. Sometimes, by the veracity of the Torah, I do not conclude until at least two hours of darkness have passed. I deliberate with them while lying down from sheer exhaustion. By nighttime, I am so weak that I can converse no longer.”

Bottom Line

The exhibit sheds light on matters of halachic import as well. There is a famous point of confusion in a comment that the Rambam makes in Mishneh Torah. At the end of Hilchos Sefer Torah, printed editions of the Rambam read that the Shiras Ha’azinu should be written across 70 lines in a sefer Torah. Elsewhere in those same halachos (Hilchos Sefer Torah 8:4), the Rambam famously states that he saw the sefer of Ben Asher, commonly known as the Aleppo Codex or the Kesser, and relied upon it to write his own sefer Torah, as it was the most authoritative version of Tanach.

In 1944, an Italian professor at Hebrew University by the name of Umberto Cassuto was granted permission to view and study the vaunted Codex but was barred from taking any photographs. Upon seeing that Shiras Ha’azinu was only 67 lines in the Kesser, Cassuto used this to bolster his claim that this was not the Codex that the Rambam relied upon, inasmuch as Rambam writes that the Shirah is 70 lines.

Shedding light on this question is an item that was on loan to the exhibit for a few months: one of the earliest manuscripts of the Mishneh Torah in existence. This manuscript was copied by a scribe, but contains the signature of the Rambam with the words “hugah m’sifri — proofread from my sefer,” and signed Moshe b’Rebbi Maimon, thus authorizing it as a reliable edition of his magnum opus. In this particular manuscript, one can observe that in Hilchos Sefer Torah, the Rambam instructs the Shirah of Ha’azinu to be written on 67 lines, in accordance with the Aleppo Codex, largely clearing up the issue. (This manuscript, on loan from Oxford Bodleian Library, was on display during the first few months of the exhibit.)

Rabbi of the Masses

In the aforementioned letter that Rambam writes to translator ibn Tibbon, in addition to describing his daily schedule, he mentions his activities on Shabbos.

“Ultimately no one is able to speak to me or spend time with me except for on Shabbos. Then the entire community or most of it comes after davening and I guide the community what they should do throughout the week, and we do a light studying, and they all go on their way. Then some of them return and after Minchah we study a little until Maariv….”

The Rambam presents himself here as a rabbi to the masses, to the simple ones that come to him on Shabbos for guidance on how to lead their lives, which brings us to one of the more fascinating items in the exhibit.

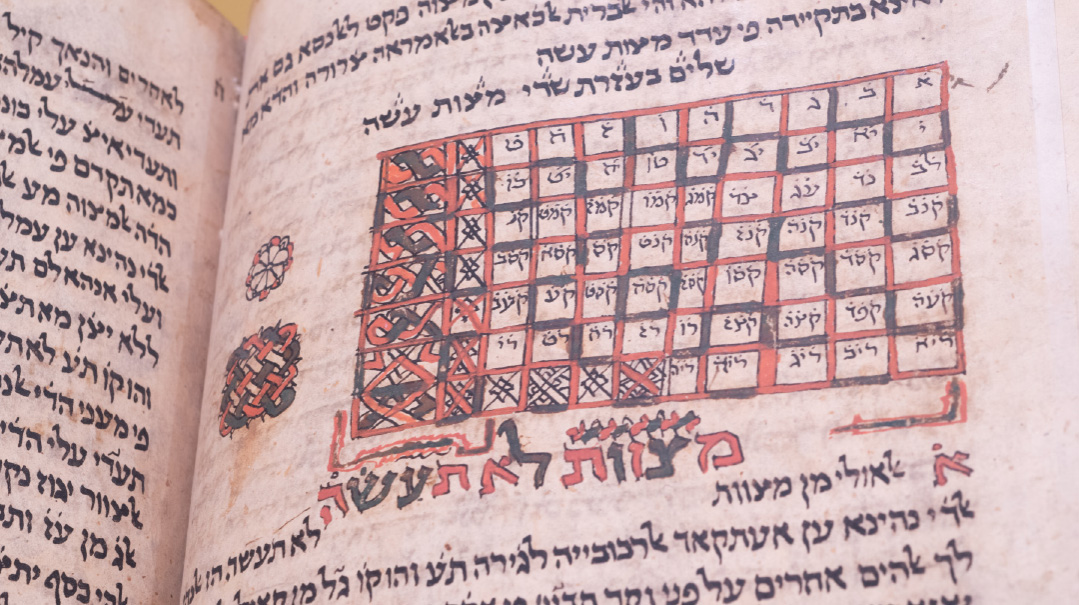

One of the foundational works of the Rambam is his Sefer Hamitzvos, his accounting of all 613 commandments in the Torah. While the Torah does not mention the number of mitzvos, Chazal had a mesorah that there were 613 (Makkos 23b). Prior to the Rambam, a few different renditions of the list of mitzvos appeared, perhaps most notably, from the Baal Halachos Gedolos. The Rambam set out to correct what he viewed as inaccurate lists, and prefaced his sefer with 14 rules delineating which mitzvos should be counted.

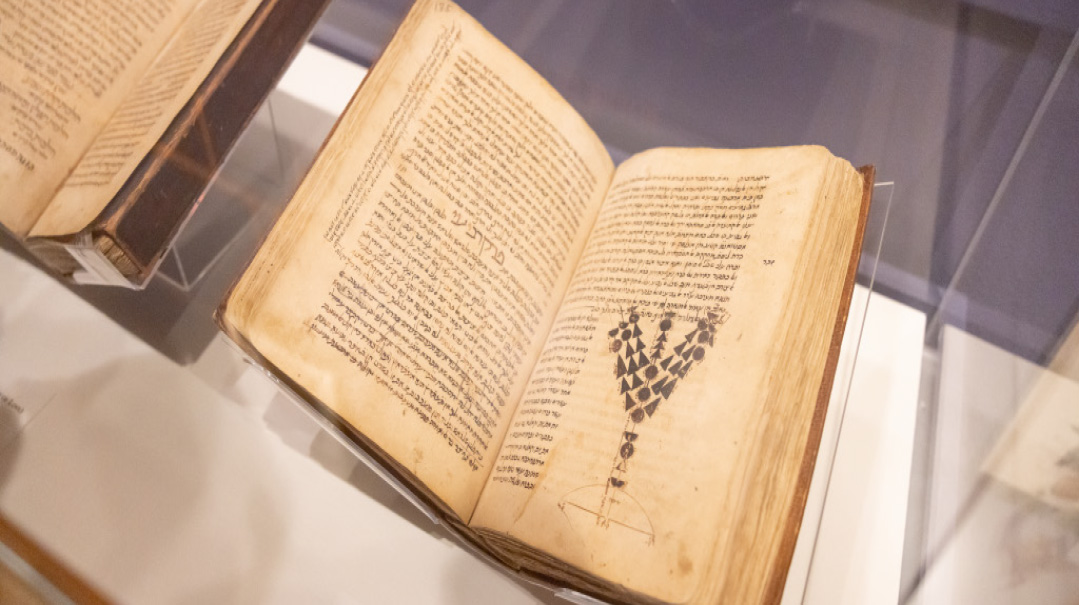

The exhibit display is that of a Yemenite manuscript of Sefer Hamitzvos written in 1492 in Judeo Arabic. The sefer in the display case is opened to the end of the listing of the mitzvos aseh, the positive commandments. On the page is an illustrated table with each box containing a reference to what seems to be numbers of mitzvos. Further examination would show that they are mitzvos which are both common and integral mitzvos, such as loving and fearing Hashem, and halachos pertaining to kashrus, Shabbos and the Yamim Tovim. The table serves as a guide to the most important and relevant of the mitzvos, presumably to assist the unlearned layperson in navigating his way through the massive corpus of halachah — a periodic table of mitzvos, if you will.

This table illustrates an identical list that Rambam himself composed, and is printed at the end of many editions of Sefer Hamitzvos. In it, Rambam summarizes different categories of mitzvos, and identifies 60 mitzvos that apply constantly to most people.

This chart was likely used as a guide to the simple Jew who lacked a level of Talmudic literacy, yet strove to serve Hashem to the best of his ability.

Branching Out

A detail of an early manuscript of the Pirush Hamishnah sheds light on an old issue. This manuscript in possession of the Oxford University’s Bodleian Library, if not in the actual handwriting of the Rambam, certainly has glosses from the Rambam, as well as an important illustration. Traditionally, it has been accepted that the proper form of the Menorah is with rounded arms. There have been those who have claimed, and perhaps most notably in recent generations, the late Lubavitcher Rebbe ztz”l, that the Rambam’s opinion was that the Menorah had straight arms. In this manuscript, there is an illustration of a menorah that doesn’t quite fit in the allotted space (remember, he was a scholar not an artist), which seems to bear straight arms.

Hartman Family Collection; Photo by Ardon Bar-Hama

In the Eyes of the Nations

Chazal say that when the pasuk refers to other nations perceiving the wisdom of the Jewish people it is specifically in the realm of calculations revolving around the constellations. The Rambam’s authority in astronomy was renowned beyond the Jewish community. In a letter penned by the scientist Sir Isaac Newton in 1699 proposing the use of the Julian calendar, he quotes the Rambam in hilchos Kiddush HaChodesh to demonstrate his solar calculations.

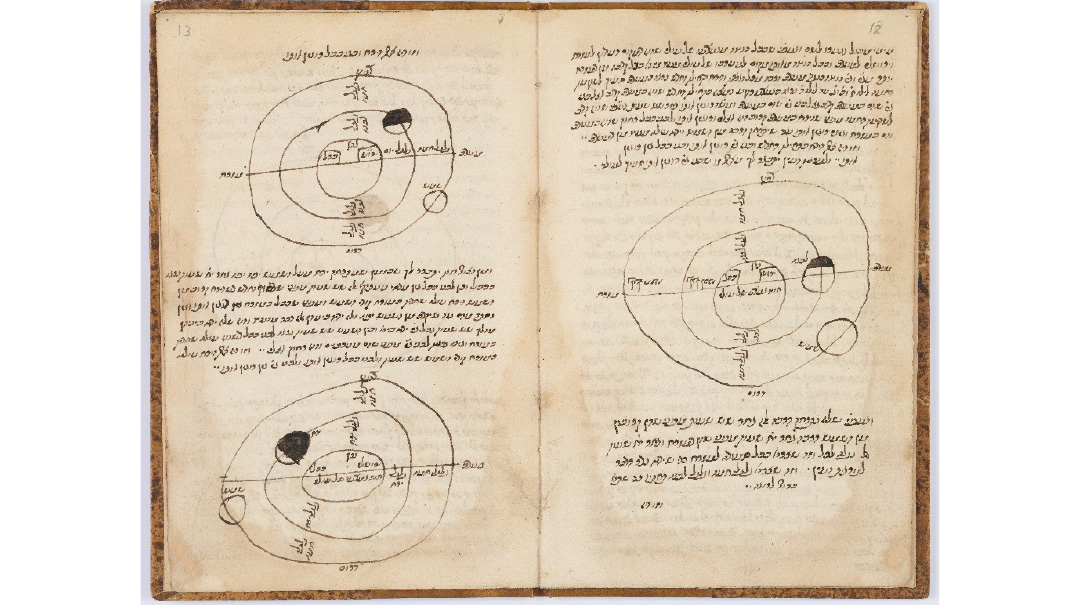

Rambam includes more solar drawings in his peirush on Maseches Rosh Hashanah. While we don’t have much from Rambam in terms of commentary on the Talmud, he mentions in his writings that he composed commentaries on at least half of Shas. While a few manuscripts of parts of this peirush have surfaced over the years, scholars tend to question their authenticity. When the peirush on Rosh Hashanah was published in Paris in 1865, it was challenged by scholars.

(However, an edition of this peirush was reissued in 1958 in New York by Rabbi S. Shulman, who responds in great detail to the skeptics, defending the authenticity of the manuscript. A more recent theory posed by Professor David Henshke claims that this peirush actually emanated from the beis medrash of the Ri Migash and was compiled by the Rambam.

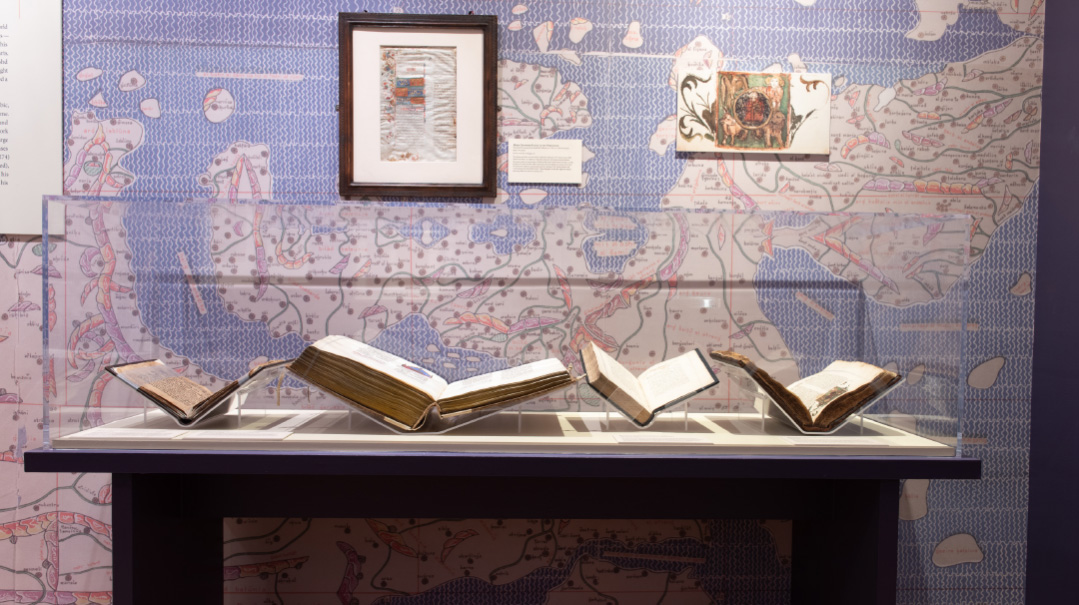

Journey Through Generations

The exhibit goes on to discuss the radiance of the Rambam and his teachings, displaying samples of countless volumes of reprints and various editions of his seforim. Many anecdotes accompany the journey of the Rambam’s seforim1 throughout history, each one a testament to the reverence and importance in which he and his work was held throughout Jewish life.

It wasn’t until the 16th century that editions of Mishneh Torah incorporated some of its commentaries as well. This trend began to take root in Constantinople and made its way to the major printing presses in Italy.

In 1550, when Rabbi Meir Katzenellenbogen, the Maharam Padua, wanted to include his commentary in a new edition of Mishneh Torah, he approached Marco Antonio Giustiniani, a local printer to arrange the publication. After a disagreement, he instead approached Alvise Bragadin, who managed a rival press, to print his commentary with them instead. In the meantime, Giustiniani went ahead and also printed the peirush of the Maharam Padua, causing major financial harm to the Katzenellenbogen-Bragadin enterprise who would not be able to sell their copies to cover their costs. This dispute led to a famous teshuvah of the Rema in which he forbade the sale of the Giustiniani edition. The discord became increasingly heated until the Church got involved, leading to great persecution and a ban on owning a set of the Talmud. The saga culminated in a tragic burning of the Talmud on the 13th and 14th of Cheshvan, 5314 (1553). The Giustiniani edition is on display in the exhibit.

A century later, also in Venice, the printing house of Domenego Vedelago issued a new edition of Mishneh Torah. This particular edition is unique due to the artwork present on the shaar blatt (title page). While many seforim feature various styles of art, the discerning eye (and seasoned cereal box examiner) will notice various differences from the norm. Moreover, the very depiction — as can be seen in the exhibit — is the peculiar image of a bearded man riding on back of a lion. The historical context here provides the key.

The edition was printed in 1665, the year that Nathan of Gaza sent a missive throughout Europe hailing Shabtai Tzvi as the messiah. He describes the scene of him riding atop a fire-breathing lion. The excitement swept throughout Europe and reached the publisher Vedelago as well, who enthusiastically incorporated this illustration on the title page of his next project.

Rambam Lives On

In 1897, a few years after the passing of the Netziv, Rav Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin, his talmidim asked the family for permission to write a biography of their father. The Netziv’s son, Rav Chaim Berlin, responded by sharing his father’s opposition to the “newfound custom” of writing biographies of great rabbanim. He pointed to the words of the Yerushalmi (Shekalim 7a) that states, “We do not erect monuments for the righteous; they are remembered through their words.” The best way to learn about the life of a talmid chacham is by studying their words — only through their teachings and writings can one gain a true appreciation for who they were.

Indeed, many years ago, Rabbi Yosef Ber Soloveichik was approached and asked to write an appreciation of the Rambam in honor of his impending 750th yahrtzeit. “What yahrtzeit?” he asked. “This is the first I’m hearing that the Rambam has died.”

The Rambam has remained alive throughout the generations in many forms, most notably in the halls of Torah study where his every word instructs, illuminates, and informs.

Visiting Maimonides Across Eight Centuries allows us to enter Rambam’s inner world via his vast world of literature, giving a close-up view of his writings and teachings, thereby scratching the surface in understanding the very life of Rambam. The exhibit, showcasing the centuries of influence that Rambam had and continues to have, demonstrates the vibrancy and perseverance of his everlasting legacy across the globe. It gives us some insight as to why MiMoshe ad Moshe, lo kam k’Moshe.

The authors wish to thank Dr. David Sclar, exhibit curator, for all of his help, as well as Rabbis Shnayor Burton, Moshe Maimon, and Menachem Silber for their insightful comments.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1001)

Oops! We could not locate your form.