For the Sake of the Children

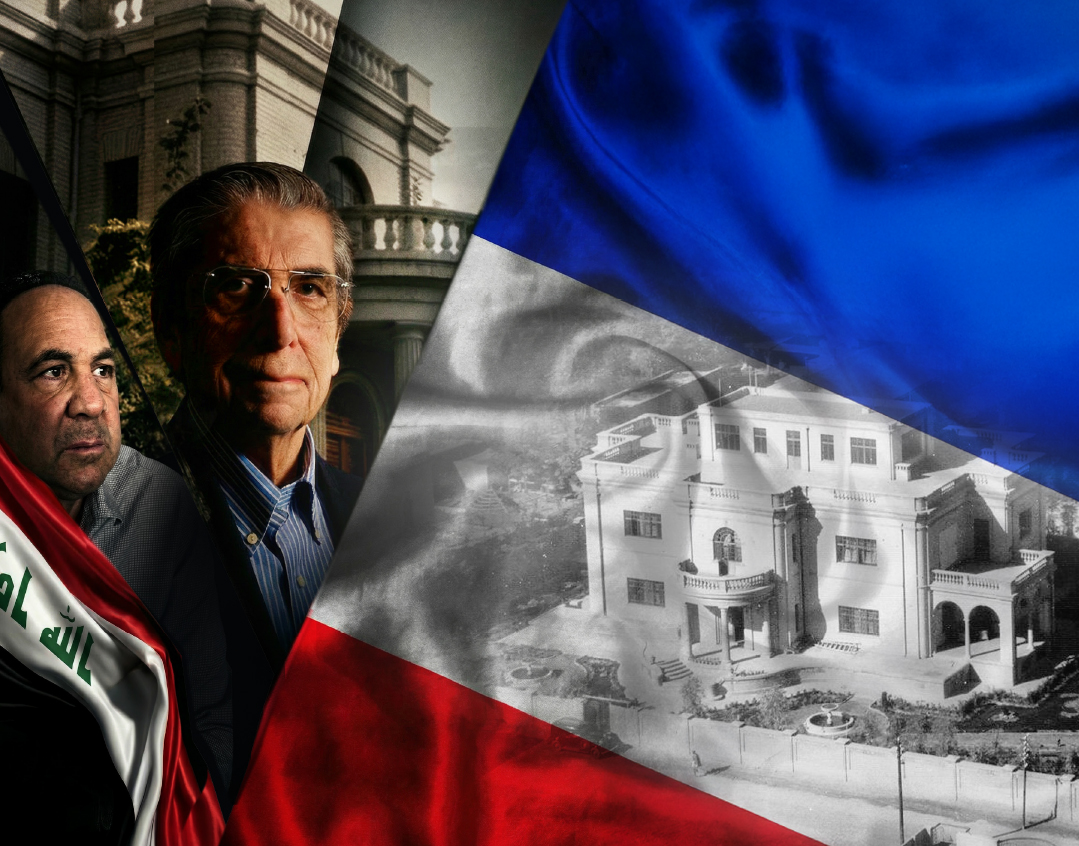

Rebbetzin Rivka Gurwicz shares a deep commonality with her father, Rav Shlomo Lorincz z”l. Because he was chair of the Knesset Finance Committee, Rabbi Lorincz’s signature appears on millions of banknotes; his thumbprint touched thousands of lives. Yet he rarely spoke about his work in the public arena, stepping back into the shadows and highlighting his interactions with the gedolim to showcase yiras Shamayim and good middos.

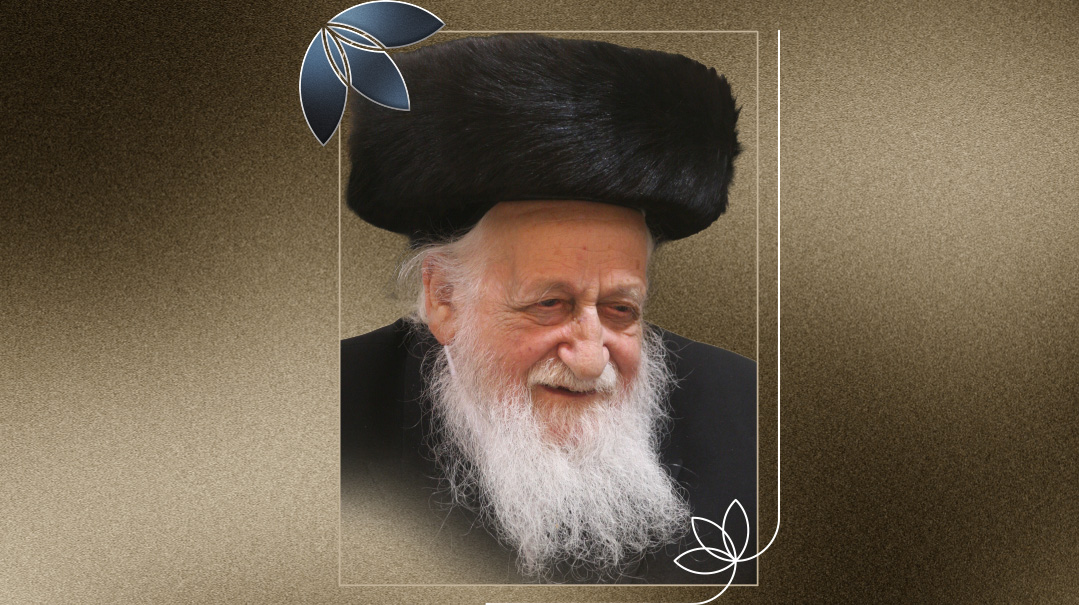

Rebbetzin Gurwicz, too, continues to touch countless lives, both at the side of her eminent husband, Rav Chaim Ozer Gurwicz of Gateshead Yeshiva, and in her work of decades training teachers in Gateshead Sem. Talking to her, though, one is struck by her humility and modesty — and the way she continually points away from herself, giving credit to her parents, her teachers, her family for her innumerable achievements.

Makings of an Askan

It may be a discussion in contemporary Jewish society — are askanim born or made? — but as the Wehrmacht rolled across Europe, there was no luxury for academic debates. Askanim were neither born, nor made, but forged by danger and desperation. Certainly this was the case for Budapest-born Rabbi Shlomo Lorincz, a talmid in Mir who was close to Rav Yerucham Levovitz.

Summoned to register at the conscription office just before the outbreak of the war, Rabbi Lorincz prepared for his army medical examination by drinking copious amounts of black coffee and eating nothing. At the end of the examination, he was given a sealed envelope to deliver to the authorities. Outside, Rabbi Lorincz opened the envelope. The letter read: This man’s physical profile is low, but mobilize him anyway.

Rabbi Lorincz tore the letter with trembling fingers while his mind darted through possibilities of escape. England, he thought, maybe he could board a ship to England. What other options could he think of? He knew that Agudas Yisrael had been trying to arrange ships to carry Jews from Budapest to Eretz Yisrael, but without success. The Jews of Budapest had paid substantial sums of money for passage, and the lack of result had caused a furor. The organizers, knowing that only Rabbi Lorincz could get the plan back on track, requested he do so.

A train journey to Romania. Dealings with a shipping company, a team of sailors, urgent telegraphs to Budapest, urgent telegraphs to the gedolim — the ship can only leave on Shabbos. The answer: Go! Rabbi Lorincz had not planned to sail on the ship he’d organized, and therefore he didn’t take leave of his parents, but he was forced by his friends to remain on board, for they feared it was his last chance. (This was, in fact, the last ship to leave, due to the Nazi invasion, although more ships had been planned.) With no luggage or possessions, without even bidding his family farewell, Rabbi Lorincz set sail on the ship to then-Palestine.

On Shabbos Shuvah, after almost two weeks at sea, they sighted land. In an attempt to evade British arrest, the ship dropped anchor a while away from shore, and they were ferried to the beach in fishing boats. “My father used to say that he didn’t even know where they were,” says Rebbetzin Gurwicz says. “They saw a little boy running along the beach. ‘Where are we?’ they asked him. ‘This is Haifa.’ ”

That night, his first in Eretz Yisrael, Rabbi Shlomo slept on the floor in a British transit camp. “As he dozed, he felt a touch on his shoulder and the question: ‘Eppes a yeshivah bochur?’

“He opened his eyes, nodded. ‘I’m coming from the Mir. Who are you?’ ”

His midnight visitor was none other than Rav Chaim Zev Finkel (father of the recently deceased Rav Aryeh Finkel). Rabbi Lorincz hastened to send him regards from his father, Reb Leizer Yudel Finkel, under whom he had learned.

Rav Finkel spirited him away and soon Rabbi Lorincz was learning in Yeshivas Heichal HaTalmud in Tel Aviv. But the turbulence of the world, and his feeling of deep responsibility toward his fellow Jew, soon brought Rabbi Lorincz to the realm of activism: helping those fleeing from Europe establish themselves in Eretz Yisrael. He was passionately concerned for the future of the children, establishing the children’s village of Sdei Chemed for orphaned child survivors, and the yeshivah Chazon Yechezkel; in 1949, he established Moshav Komemiyus and Kfar Gidon to provide Torah-observant survivors both a home and a livelihood.

“That was the future. Children were the future,” says Rebbetzin Gurwicz emphatically. It’s not hard to hear the echo of her father z”l in her words. Rav and Rebbetzin Gurwicz are fitting heirs to this mission: Rav Gurwicz has shaped and nurtured his talmidim, and the Rebbetzin has fashioned teachers out of girls with diverse personalities and strengths.

In Focus

Rebbetzin Rivka Gurwicz, the first child of Rabbi Shlomo and Mrs. Marta Lorincz, never realized that she was born into an exceptional home. Her father’s piercing focus on the klal’s needs — whether setting up homes for survivors, fighting against the conscription of yeshivah bochurim and religious girls, or raising money for a chareidi educational system in Israel (Chinuch Atzmai) — weren’t subjects for suppertime conversation. Stories were not told of Rabbi Shlomo’s dealings with Ben-Gurion, Harry Truman, or Golda Meir. Stories were told of Reb Yerucham, the Chazon Ish, and the Brisker Rav.

“When my brother was around five, he was asked in school what our father’s job was. He’d heard the word Knesset here and there, so he screwed up his face and thought it through. ‘My father is a shamash in a beit Knesset,’ he told his teacher.” Rebbetzin Gurwicz elaborates: “My father never wanted anyone of his children to go into politics. He refrained from inviting any of these prominent personalities to our simchahs unless it was necessary for the sake of the klal — he kept his private life private. And for the last 30 years of his life, he just sat and learned.” No wonder that Rabbi Lorincz’s children are counted among the preeminent personalities of today’s Torah world.

The inside story of Rabbi Lorincz’s incredible achievements, says Rebbetzin Gurwicz, lies in one word: focus.

“To achieve something, you have to know what you have to do — everything else, delegate. If my father had been involved in all the endless details of life, he would never have had time to achieve everything he did.”

This attitude extended to his home life. “Both because of this shittah, and also because of his aristocratic Hungarian upbringing — with its strong emphasis on the distinct roles of men and women — my father never did anything around the house,” Rebbetzin Gurwicz recalls. “He never changed a baby, went shopping, or even stepped foot in the kitchen. But no matter how tight the finances, my mother always had help.

“Although my mother did help out in their printing business, she never officially worked. She just stood in for my father, because he was so busy.” Rebbetzin Gurwicz acknowledges that her own home differs in this respect, “in part because my husband wanted more day-to-day connection with the children. What my parents had was not something to emulate, but to learn from.”

Rebbetzin Rivka has seven younger siblings, and she remembers the times her mother was weak from giving birth and caring for a newborn. “For us children, it was difficult,” she says. “But my father explained that when a mother gives birth, that’s the time for her and the baby, and everyone must be satisfied with less.”

Mrs. Lorincz was an equal, if unseen, partner in all her husband’s endeavors. In 1948, with the War of Independence still raging, Rabbi Lorincz was asked to embark on a six-month fundraising trip in the States. Unsure of whether he should travel in a time of political upheaval — and in his poor health — Rabbi Lorincz asked the Chazon Ish for guidance. The Chazon Ish told Rabbi Lorincz that the zechus of the mitzvah would protect him from any harm. But only on one condition: “Does your wife wholeheartedly support you going?”

Years later, when Rav Gurwicz was asked to join the hanhalah of Gateshead Yeshiva, Rebbetzin Gurwicz drew upon her mother’s example of allowing her father to travel for the sake of the klal. “We weren’t going to uproot the children unless we were serious about the move. So my husband went alone for six months before we decided to move the family. Of course, it wasn’t like it had been for my parents. They just had letters. We had phones and could speak once a week!”

Her mother was a role model in many ways. “My mother put herself in the shadow, but without saying a word, she showed us that the important thing in life was to help others. My mother didn’t have a social life, in the way you’d describe it today,” Rebbetzin Gurwicz explains. “Her natural shyness played a role, as did her conviction that a woman’s place was to facilitate her husband’s mission.”

Yet she was close to Rav Shach’s wife Rebbetzin Gittel Shach, and Rebbetzin Ahuva Berman, wife of Reb Shlomo Berman, a maggid shiur in Yeshivas Ponevezh. On occasion, when Rabbi Lorincz went to call on Rav Shach, his wife would accompany him. Rebbetzin Shach was bedbound for years, and Mrs. Lorincz found her an aide, Mrs. Lorincz would also sit and talk with the Rebbetzin. More than a relationship built on the ups and downs of everyday life, theirs was a connection of the soul.

Mrs. Lorincz’s devotion to her husband was such that concern for him occupied her during her last illness. “‘Who will look after Abba when I’m gone?’ she asked us. ‘We will,’ I answered. That was enough; she never mentioned it again. Her duty would be fulfilled.”

Rabbi Lorincz was first elected to the Knesset in 1951. He served until 1984. “My father had a fantastic relationship with secular Jews. He was a diplomat; he knew how to build a relationship while maintaining a firm stance on matters of principle. He didn’t move a step without consulting the gedolim.” Many speeches that Rabbi Lorincz gave during his decades in the Knesset were looked over by the Chazon Ish and later by the Brisker Rav, and he aspired to be nothing more — and nothing less — than their faithful emissary.

After his retirement from public life, Rabbi Lorincz published Milu’ei Shlomo, a sefer that discusses sugyas in Gemara. Later, when his wife became ill and he found concentration difficult, Rabbi Lorincz penned a two-volume sefer, B’mechitazam, which was later translated into other languages, including “In their Shadows,” in English. These volumes document the rulings he received from the gedolim concerning his political involvements. In his introduction, Rabbi Lorincz emphasizes that all what he wrote, including the stories, are not for entertainment, but “to provide a springboard for spiritual growth.”

Spiritual Legacies

It was in this rarified atmosphere that Rebbetzin Rivka spent her formative years. In 1963, needing more depth and stimulation than offered by her local Bais Yaakov, Rebbetzin Gurwicz flew to England and stepped inside 50 Bewick Road, the home of Gateshead Seminary.

A stoic attitude proved her best friend as she negotiated a foreign world. “I hardly knew English. It was hard for me, socially, but I just got on with it. Most girls did.” Rebbetzin Gurwicz went home only once in her three years there.

Soon, there was deep intellectual and spiritual fulfillment: “Back then, what girl could understand a midrash? In sem, under the guidance of Rabbi Mordechai Miller z”l, we were able to fathom the depths of midrashim. The same applies to all the other lessons.”

On her first Succos in Gateshead, Rebbetzin Gurwicz joined Mr. Avrohom Kohn z”l, the legendary founder of the seminary, for a Yom Tov seudah. “I didn’t know much English, but I was learning. I knew that the verb to feed is related to eating. When Mrs. Kohn offered me a second helping, I said, ‘Thank you, but I’m fed up.’ ”

The year Rebbetzin Gurwicz came to English shores, her chassan-to-be, Rav Chaim Ozer Gurwicz, youngest child of Rav Leib and Liba Gurwicz and grandson of Rav Elya, set off to Eretz Yisrael, where he learned in Brisk. Three years later, when Rebbetzin Rivka returned home, Rav Yoshe Ber Soloveitchik, Rosh Yeshivas Brisk, a close friend of Rabbi Lorincz — “they could sit and talk for hours” — suggested the shidduch.

“If I hadn’t gone to Gateshead,” Rebbetzin Rivka muses, “I don’t know if the shidduch would have come about.”

Rav Chaim Ozer brought his own spiritual legacy to their marriage. “Rav Chaim Ozer often talks of his righteous mother, Rebbetzin Liba.” Rebbetzin Liba was engaged to be married to Rav Leib Gurwicz when her mother passed away at the age of 49, leaving 13 orphans. She, and her new husband, Rav Leib, moved in to raise the children.

“You know, when a sister and brother-in-law raise a family, it’s an unnatural situation. They can be criticized, a rift can result. But my parents-in-law were the king and queen of the family. It was so clear that even if they made a mistake, it wasn’t from selfishness.” Unbelievably, they never raised their voices. Rebbetzin Gurwicz gives a wry laugh. “I wish I could say the same thing of myself.”

It was in Rav Elya’s home in London, with its admixture of siblings and children, giving and truth, that Rav Chaim Ozer lived until he was five. Then, his family moved to Gateshead for his father to become rosh yeshivah, and Reb Elya remained in London and later moved to Eretz Yisrael.

Blessed Years

After Rav Chaim Ozer and Rebbetzin Rivka married, Rabbi Lorincz bought the young couple an apartment in Mattersdorf. Rebbetzin Gurwicz embarked on her vocation as a teacher and Rav Chaim Ozer learned in Brisk. Rebbetzin Gurwicz reflects on that period of her life: “He came back late at night and I didn’t expect anything different. I gave my husband what my mother gave my father. Though my husband helped me a bit more than my father helped my mother.”

After her first two children were born, Rebbetzin Gurwicz gave up classroom teaching: “I realized that I couldn’t do it all. Not be a perfect wife and a perfect mother and a perfect teacher.”

Rav Gurwicz began giving a shiur, first in Zohar HaTorah, the yeshivah of Rav Betzalel Toledano, and later in Kol Yaakov, under the helm of Rav Ades in Bayit V’gan. “Rav Ades wanted a yeshivah that would have half Ashkenazi boys and half Sephardi boys. These were very blessed years.”

The Gurwicz family grew: they had two sons and four daughters, and Rebbetzin Gurwicz worked on building a home that would be a foundation of security for her children. “When I took my daughter to preschool, I’d stand at the window and wave goodbye. One day, I came a little early to pick her up. So I peeked in the window. My daughter caught my eye and we waved. Later, she said, ‘Wow, you waited for me the whole day?’ For me, that was a huge compliment.”

Rebbetzin Gurwicz’s formidable intellect was no contradiction to her love of home life. “I always read and gave shiurim, and then there was the kibbud horim — any time my parents needed anything, I dropped everything. And I did chesed, but mostly in the house — people would come and talk to me at home — so I was there for the children.” Rebbetzin Gurwicz also enjoyed interacting with people of all stripes and types: “I learned this from my father.”

Rebbetzin Gurwicz tells of how her father cultivated friendships with the philanthropists who donated to his pet projects — Moshav Komemiyus, the Children’s Village of Sdei Chemed, Chinuch Atzmai. “None of the donors were religious. But my father never said, ‘He’s got millions, of course he can give a little.’ He said, ‘Never underestimate how difficult it is for these people to give away their money. They are so great, we have to admire them.’ ”

Many philanthropists paid Rabbi Lorincz and his family visits in their home — often asking him advice about their children or other personal issues — and Rebbetzin Gurwicz remembers these visits vividly. “We had to make sure everything looked perfect, and to be quiet!”

When their youngest child was five, Rav Chaim Ozer’s father, Rav Leib Gurwicz — one of the two “lions of Gateshead,” as he was dubbed by Rav Dessler — was niftar. A delegation from Gateshead Yeshiva approached Rav Shach, asking him to use his influence to persuade Rav Chaim Ozer Gurwicz and his family to return to Gateshead to take their place among the yeshivah leadership.

The family had deep roots in Eretz Yisrael and it was an immensely difficult move. The actual decision, though, was easy: “Rav Shach told us to do it. So you swallow your tears and put your ego in your pocket.”

Still, it was painful for Rebbetzin Gurwicz to leave behind her aging parents. Rabbi Lorincz had bought a burial plot on Har Hazeisim, but when his longtime chavrusa, Rav Simcha Wasserman, was niftar on 2 Cheshvan 1993, he changed his mind. Rav Simcha was buried on Har Hamenuchos, and Rabbi Lorincz then sold his plot and bought a new one near Reb Simcha on Har Hamenuchos. It was a final act of friendship.

“Rav Simcha had no children, so who will go and daven at his kever, especially on his yahrtzeit?” he told his children. “But when you’ll daven at my kever, you’ll also go to his.”

Seventeen years later, in 2009, Rabbi Lorincz passed away. The date was Rosh Chodesh Cheshvan. In keeping with the minhag not to visit a kever on Rosh Chodesh, every year, Rabbi Lorincz’s children visit the kever a day after the yahrtzeit, on the 2nd of Cheshvan. They also visit Rav Simcha’s grave — on his yahrtzeit.

Back In the Classroom

Soon after their move, Rebbetzin Gurwicz was invited to join the faculty of Gateshead Seminary, training the talmidos to become teachers. In this position, she felt many of the attitudes to chinuch she’d absorbed from her father concretize into an approach. Pithily expressed, “The best teachers are the ones who show us where to look, but don’t tell us what to see.”

Many conceptualize teaching as the act of pouring from a full container to an empty one. Rebbetzin Gurwicz disagrees: “The point of teaching is to give the student information and let her work it out for herself. This develops her imagination and knowledge and skills. For every part of a lesson, whether an explanation or a story, you have to ask yourself: what’s my objective? And the answer should always be, to develop their personalities and show them what they can be and achieve.

“It’s very frightening,” she continues. “You know, if you teach math and the students don’t like the subject, big deal. But when you teach limudei kodesh, you’re molding Yidden. Yet we have to do it, even if it’s frightening.” One of the ways to achieve a lasting love for kodesh subjects, she says, is to identify with what you say: “the children will hear it in your voice. Also, prepare as much as you can — and then pitch the level correctly, so that the children are excited by what you teach.”

Turning to chinuch habanim, Rebbetzin Gurwicz emphasizes that everything needs siyata d’Shmaya. On a practical level, she eschews magic formulae: how much to expose a child versus how much to insulate, the degree of love versus discipline — all, she avers, depends upon the nature of the child and the situation. What’s paramount in the home is authenticity. “Children feel and get what’s emes for the parents. They pick up on the way you speak to your spouse, your parents, your guests — and of course, to them. And they see whom you admire: a man who made millions or a gadol. They sense your truth.”

She tells of how her father, as a politician, had to read the daily newspaper. Of their own volition, the children never touched the paper — it was viewed as something their father needed for his job. If the newspaper was lying around on Shabbos, Rabbi Lorincz would ask a child to put it away — “for me, it’s muktzeh,” he told them. “That was his truth, and we sensed it. He was machshiv Torah, not politics. And none of us became politicians.”

As well, Rebbetzin Gurwicz recommends, “Don’t allow your children to hunger for something. As much as you can, give them a taste of what they want in a permitted way. If a child wants a T-shirt you think is inappropriate, you could buy it for him to wear for pajamas. If a girl wants something more modern, she could wear it for exercising. In the end, they look back on themselves and laugh.”

All of the Gurwicz children live in Eretz Yisrael and Rebbetzin Gurwicz longs to return someday. Which brings us to one last story about her father: In a conversation with then-prime minister Golda Meir, she confided that she often had trouble sleeping at night.

“Because of the country’s security situation? Or because of the economy?” Rabbi Lorincz asked.

“No, no, all these problems can be solved,” Golda Meir replied. “I’m afraid that one day my children and grandchildren will ask themselves, ‘Why fight so hard? Why face so many difficulties. In America, life is more comfortable.’ And they’ll leave.”

Golda Meir lapsed into silence. Then she turned to Rabbi Lorincz. “I have no such worries about your children or grandchildren. The connection they have with Eretz Yisrael is one of the soul.”

Just like her connection with Eretz Yisrael bridges the ocean, Rebbetzin Gurwicz’s connection with the gadlus of yesteryear brings spiritual greatness to life, today. In the countless talmidim her husband has impacted, in the scores of teachers she’s shaped, we hear the echo of her father’s conviction: “Children are the future.”

The Brisker Rav’s Esrog

“Every Succos, my father would tell us the story of the Brisker Rav’s esrog. We’d sit for an hour, listening, and we were always enthralled,” says Rebbetzin Gurwicz.

Succos 1958. The Brisker Rav sent someone to Morocco to bring him a mehudar esrog. But when the man arrived back in Israel, the esrog was confiscated at customs. Apparently, there was fear of infestation that could spread to Israeli agriculture, and no fruit was allowed in the country. The Brisker Rav asked Rabbi Lorincz to intervene, explaining how important it was that he perform the mitzvah with an esrog that had definitely not been grafted. Rabbi Lorincz traveled directly to the airport, and was referred from official to official — none of whom where able to help.

As Yom Tov approached, Rabbi Lorincz tried to locate the chief administrator of the airport, to see if he could help. The man had already left for home. Rabbi Lorincz called him, but to no avail. There was no way to retrieve the esrog before Yom Tov and Rabbi Lorincz headed back to Yerushalayim.

The Brisker Rav was distraught when he heard, and he implored Rabbi Lorincz to try again on Chol Hamoed. Meanwhile, the manager of the airport had gone on vacation, and no one was able to locate him. It was Hoshanah Rabba when Rabbi Lorincz connected to the chief administrator, who told him that he had no authorization to hand over the esrog — for this, Rabbi Lorincz would have to approach the minister of agriculture.

Rabbi Lorincz soon found out that the minister of agriculture had been hospitalized. He rushed to the hospital. The minister agreed to release the esrog, but he had no official stationary, without which his instructions wouldn’t be valid. Rabbi Lorincz rushed to the Ministry of Agriculture, brought some stationary to the hospital, and the minister signed his consent for the esrog’s release.

Rabbi Lorincz raced to the airport, but when he arrived, the office was closed. Shmini Atzeres was fast approaching — and no esrog. Rabbi Lorincz was filled with dread at the prospect of returning to the Brisker Rav and telling him that there was no chance of using his precious esrog for the mitzvah of arba minim.

But in the home of the Brisker Rav, Rabbi Lorincz was greeted with a smile. “No esrog?” the Rav asked. Rabbi Lorincz confirmed. After a week of tension and unremitting effort, Rabbi Lorincz was surprised that the Brisker Rav was in a jovial mood. When he asked, the Rav responded with a story.

A resident of Brisk asked the Brisker Rav to persuade his mother to sell her home in Rogabe, some distance from Brisk, and move to Brisk to be near her family. The next time she was in Brisk, the Brisker Rav called her in and asked her to consider the move.

“I won’t consider it,” she said. And this was the reason she told him: “All of his life, my grandfather saved, kopek by kopek, so that one day he’d be able to buy an esrog for Succos. When he was a very old man, he took the bag of coins and went to the esrog dealer. He counted out all the pennies, but there wasn’t enough for an esrog. Bitterly disappointed, he returned home.

“My grandmother told him, “We’re getting older, and we’ve wanted to do this all our lives. Let’s sell our home, and rent a small place. With some of the money, we can buy an esrog.”

“So my grandparents sold their home and returned to the esrog dealer, where they bought the most beautiful esrog. They were thrilled. Come Succos, the Jews in the village asked to come and use the esrog. As one man held it up to admire it, the esrog slipped through his fingers and dropped onto the floor. The pitom broke off. My grandmother was charged with the task of telling her husband that their precious esrog was not kosher.

“She prepared him for the news, giving such broad hints that he was terrified that someone in the family had passed away. When he heard that his esrog was pasul, he said, ‘The same Almighty Who instructed me to take an esrog also said that one must not get angry. If I don’t have an esrog, then I’m patur from performing the mitzvah.”

The woman explained to the Brisker Rav: “Every day I pass the home my grandparents sold and I remember their love of mitzvos and their love of the Almighty. How can I move from there?”

The Brisker Rav turned to Rabbi Lorincz. “While I thought there was a way we could get the esrog, we did everything we could. But now I see that there’s no way we can get it, I think of those words: If I have no esrog, I’m patur from the mitzvah.” The Brisker Rav’s warm smile testified to his complete acceptance of Hashem’s Will.

(Originally featured in Family First, Issue 513)

Oops! We could not locate your form.