Footnote to Tragedy

Another drama unfolded in Neve Yaakov, almost simultaneously with the terrorist attack

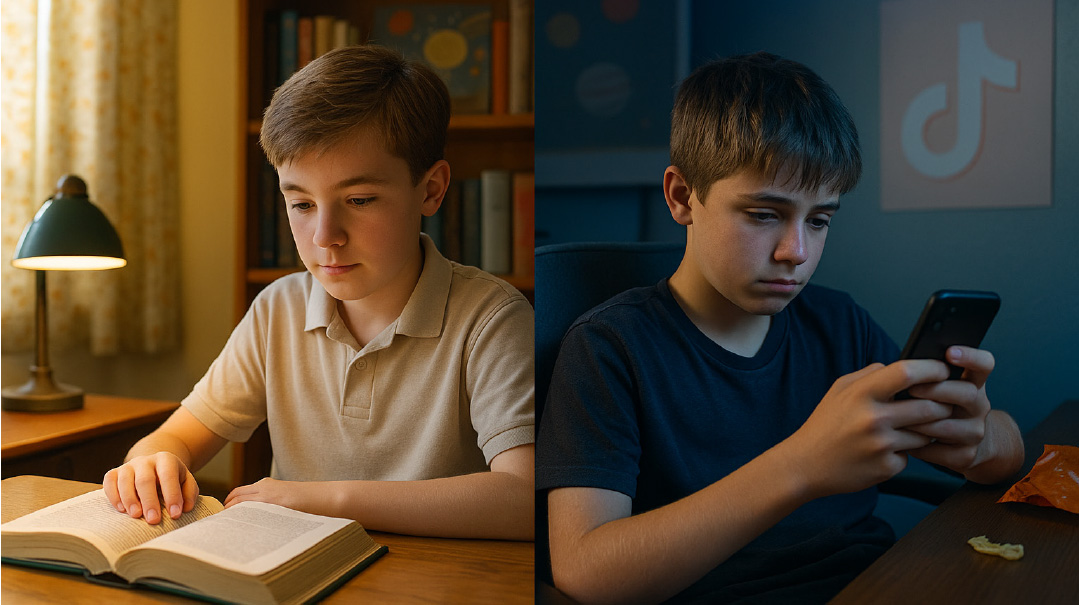

Photo: Flash90

Shabbos Parshas Bo will long be remembered as the date of the tragic terrorist murder of six Jews and a dedicated Ukrainian caregiver in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Neve Yaakov. Another drama unfolded in Neve Yaakov, almost simultaneously with the terrorist attack, involving 70 post–high school students spending a year in Mechinah Gal’on. They were in Neve Yaakov for what would have been the first complete Shabbos that most of them had ever experienced.

Mechinah Gal’on is one of the three Nachshon mechinot (pre-induction academies) founded by Maj. (res.) Gilad Olshtein in the wake of the Rabin assassination. About a decade ago, Olshtein approached Mrs. Tzila Schneider, the founder and moving force behind Kesher Yehudi. He wanted his charges to understand their role in Jewish history and why the defense of the collective Jewish people in Israel is worth risking their lives for. And he sensed that the Torah community might have some answers to those questions. Mrs. Schneider jumped at the opportunity to create such a program for Israel’s most idealistic youth, many of whom will go on to become officers in the IDF and societal leaders.

The original three mechinot in the Kesher Yehudi program have grown over less than a decade to 27, with a total of approximately 1,350 students. That rapid growth owes largely to the enthusiastic cheerleading of Olshtein. He used his position on the presidium of the national council of mechinot (of which there are about 50) to continually talk up the Kesher Yehudi program.

The basic program consists of ten meetings between mechinah members and young avreichim and their wives from a nearby Torah community. Each mechinah member is paired with a study partner for the year, and once a month the two spend three hours together discussing and learning materials related to essential issues in Torah thought — e.g., Creation, Shabbat, emunah, prayer, the meaning of “love your fellow Jew as yourself,” the role of women in Torah society, the transmission of Torah, etc.

At least once a year, mechinah members are hosted for a full Shabbos, in the nearby Torah community from which their chavrusas are drawn. Spending a Shabbos together with the chavrusa and his or her family is the capstone of the deep relationship that has been forming over the course of the year, and which will, in many cases, last long after the mechinah ends and its members have entered the IDF.

PARSHAS BO WAS Mechinah Gal’on’s Shabbos in Neve Yaakov, the community in which their chavrusas live. The mechinah members initially gathered in the Ateret Avraham shul, in front of which the terrorist would launch his deadly attack a few hours later. They were supposed to spend the night in two school buildings flanking the shul on either side.

Even before Shabbos began, the excitement of the mechinah members was palpable. Rabbi Yitzchak Farhi, one of the Kesher Yehudi volunteers, brought over a pair of tefillin, which he donated to Mechinah Gal’on for whoever wanted to use them. Three mechinah members donned tefillin before Shabbos. Another mechinah member lifted his shirt to reveal tzitzis that he had purchased especially “lichvod Shabbat,” and he wore them out the entire evening. After davening, yet another mechinah member approached the aron kodesh and remained there for at least five minutes with his arms spread on the parochet in intense prayer.

The original plan was for the mechinah members to congregate again at 8:30 p.m. for an oneg Shabbos with their chavrusas and other community members. That would have been precisely at the time and place the terrorist launched his deadly rampage. But many of the mechinah members complained that they wanted to spend more time with their chavrusas at the Shabbos table, and the gathering time was pushed back to 9 p.m., by which time the terrorist had been killed by security forces.

Chagit Shachor, the overall director of the mechinah program and a Neve Yaakov resident, arrived at the school building to help prepare for the oneg Shabbos, just moments after the attack ended, unaware of what had just taken place. But soon the phones the mechinah members had left in their backpacks in order to experience a full Shabbos began ringing nonstop with calls from frantic parents seeking to make sure that their children were safe. Some were already on their way to the neighborhood.

Gathering all the mechinah members was no easy task. Some wandered in around the appointed hour from their Leil Shabbos meals. Others had heard the police announcing over loudspeakers that residents should stay at home until they could be sure that there were no other terrorists loose in the neighborhood. And some were just having too good a time with their hosts to pull themselves away.

Meanwhile, the Zaks family, just opposite Ateret Avraham, opened up their home for an oneg Shabbos when the police declared the school buildings out-of-bounds. Male mechinah members first gathered on the Zakses’ large balcony, and then at the Shabbos table. Other mechinah members sat in the courtyard of their home. All were abuzz with the realization of how close they had come to being directly in the line of the terrorist’s lethal attack.

The Kesher Yehudi volunteers engaged their chavrusas in deep discussions about emunah in the face of tragedy. And in singing — “Kol Ha’olam Kulo Gesher Tzar Me’od,” “Katonti Mikol Hachasadim,” and traditional Shabbos niggunim.

Word of the presence of seventy secular youth in the neighborhood had spread, and the mechinah members were overwhelmed with invitations to Shabbos meals and to sleep over from complete strangers not even involved with Kesher Yehudi. That outpouring of chesed left a deep impression on the mechinah members, many of whom commented that they felt for the first time how all Jews are really part of one big family.

That is, in fact, the central message of Kesher Yehudi, whose mission statement is to overcome the deep divisions in the Israeli Jewish community through emphasizing our shared inheritance of Torah. The close relationships that develop over ten months of lengthy meetings with the same chavrusa have proven the most effective means possible of overcoming stereotypes. And the shared brush with death last Shabbos and the attendant rush of emotions only served to deepen the connections.

EVENTUALLY, the heads of Mechinah Gal’on arrived in Neve Yaakov, along with several parents. The former told the Kesher Yehudi organizers that the police did not want the mechinah members to sleep in the school buildings and that they felt that the mechinah members should all stay together to process the events. Around 1:30 a.m., two buses returned the mechinah members to their base.

But not before many of the guests had complained that they felt cheated of their full Shabbat experience. Already on Motzaei Shabbos, the Kesher Yehudi organizers started receiving calls from mechinah members seeking a raincheck for the Shabbaton and offering a concrete proposal that if a Shabbos could not be found in the course of the rest of the mechinah year, they would all gather for the first Shabbos in July.

The current director of Mechinah Gal’on has not always shown the same enthusiasm for the Kesher Yehudi program as his predecessor Gilad Olshtein, who now heads Yad Vashem’s School for Holocaust Studies. But in the aftermath of the tragic events of Neve Yaakov, he sent a message to the head of the volunteers from Neve Yaakov:

We told our students today that we see how at the end of the day, after all the chasms and strife, all Klal Yisrael is bound one to another with bonds of mutual responsibility. [We saw] how amid all the shock and confusion, the [Kesher Yehudi] staff in Neve Yaakov acted in such a phenomenal way to help us and to be together with us. And we will have to think of a way to make our next meeting an expression of hakarat hatov.

Within days of their return to their base, the mechinah members had organized an online fundraising drive for the family of Asher Natan Morali, 14, whose broken father they had heard speaking on television. The knowledge that they could have easily been in the same place as the slain boy brought home powerfully that they and the young boy with long peyos were not so different from one another after all.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 948. Yonoson Rosenblum may be contacted directly at rosenblum@mishpacha.com)

Oops! We could not locate your form.