Foil Pans and the Secret of Simchah

The Torah itself explicitly reveals to us the secret to achieving simchas Yom Tov

There is spiritual depth to the 9-by-13 pan, of this I am certain. As evidence, consider this: For decades it has been the chosen receptacle for potato kugels worldwide.

I believe one reason might be that 913 is the gematria of “Bereishis” — like, the very foundation of the universe hints to a silver foil pan, or, at least the kugel inside it.

But there’s even more. Call me crazy, but I think 9-by-13s have souls of their own. They’re alive. Somewhat.

Watch the progression of a 9-by-13 over the course of a three-day Yom Tov. It begins gleaming and proud, radiating elegance and refined purpose.

The following day, it shows less confidence. Some of the gleam has faded, its rims are sagging in forthcoming surrender.

By day three, it’s over. A blob of mush (forensic analysis shows this to be leftover shriveled cauliflower latkes) sits in its middle, snickering at its pathetic surroundings. The once-proud silver foil pan is flailing for its final breaths.

The silver foil pan lives and dies, but here’s the really uncanny part: This progression is directly synchronized with that of its human counterparts.

I too enter Yom Tov feeling optimistic. There’s a bounce to my step, a smile on my face.

The next morning, the spirits have begun to dwindle. The walk to shul is more of a trudge, the bounce in my step reduced to a tired shuffle.

By the second night of Yom Tov, my disintegration mirrors the foil pan’s fated demise. We have continued our shared spiral downward.

And by the following day, having likely collapsed in a stupor on the couch the night prior, I arise in a ball of disheveled wrinkledness. It’s over.

I’m dead like a foil pan.

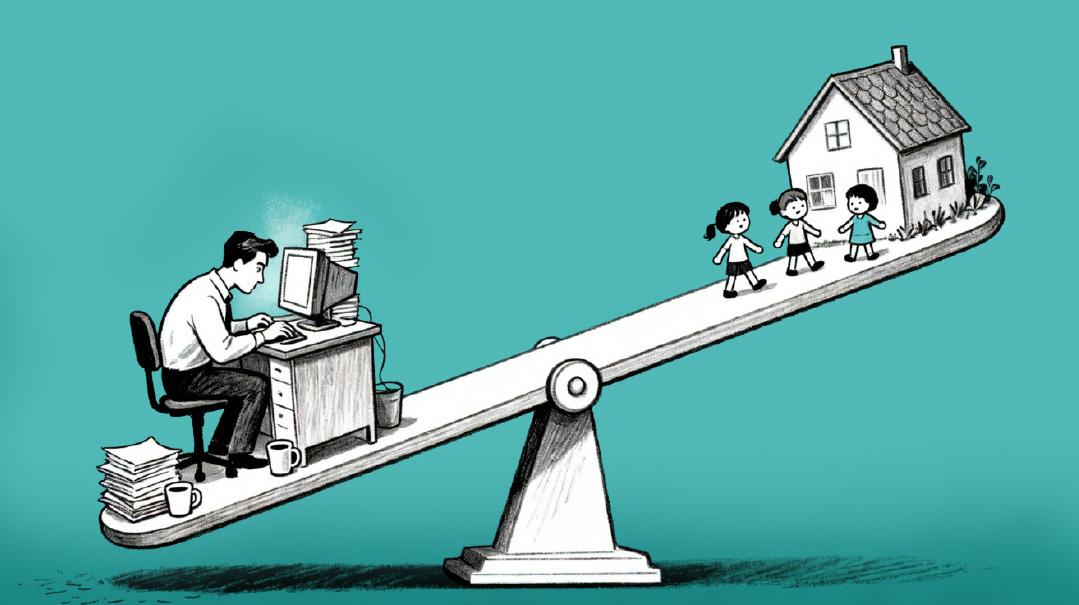

Yes, I’m being a bit melodramatic here, and just a tad imaginative — but you get my drift. Yom Tov spirits are hard to maintain. And while simchah is central to every Yom Tov, it isn’t as easy as it sounds. In fact, it is said in the name of no less than the Vilna Gaon that on Succos, when we are graced with so many mitzvos, the most difficult one to fulfill is v’samachta b’chagecha — “and you shall rejoice on your chag.”

This is the Vilna Gaon talking. Foil pans may take comfort in that.

But if Hashem instructs us to be b’simchah on Yom Tov, then shouldn’t we assume that there is a workable method for doing so? Did Hashem create Yom Tov knowing that, through no fault of our own, we will die the death of a 9-by-13?

Of course not. And in fact, the Torah itself explicitly reveals to us the secret to achieving simchas Yom Tov.

The end of parshas Re’eh is one of the several sections in the Torah dedicated to instruction on the Shalosh Regalim. In describing the obligations of Chag HaShavuos, the pasuk says “You shall rejoice… with your son and daughter, your male and female slave, the Levi in your communities, and the stranger, the orphan, and the widow in your midst…”

Rashi comments that the pasuk lays out two lists of four. There is the “son, daughter, male slave, female slave,” then there is the “Levi, stranger, orphan, and widow.” Says Rashi, the latter four correspond with the former. While you have every motivation to give your son, daughter, and slaves a wonderful Yom Tov, Hashem tells us to place equal focus on the “Levi, stranger, orphan, and widow.” In Rashi’s words, “Im atah mesameiach es Sheli, Ani mesameiach es shelcha — if you gladden ‘Mine,’ I will gladden ‘yours.’ ”

The key to securing true Yom Tov joy for the members of your home is to open it to those who so desperately need one.

So there you have it. The 9-by-13s can straighten their backs and polish their faces. By going out of your way to ensure simchah to others outside of your immediate household, you will be Divinely blessed with simchas Yom Tov yourself.

No need to crumple into oblivion by Day Three.

But it goes deeper than that. As it turns out, the link between “opening your home” and enjoying true simchah is an inherent one.

It is brought in the name of Rav Pinchas of Koritz that the words “hachnassas orchim” share the same gematria, 800, as the words “v’hayisa ach sameiach — and you should be only happy.”

Fulfilling the mitzvah of hachnassas orchim, says Rav Pinchas of Koritz, brings one to happiness — and this applies all year around.

It’s easier said than done and, for those who struggle with hachnassas orchim, who find opening their homes to strangers difficult (and yes, I’m among them), please indulge me with a vort — a small thought of my own. I think you may find it kedai. Here goes:

We quoted Rav Pinchas of Koritz who taught us that hachnassas orchim can merit simchah — the words hachnassas orchim sharing gematrias with v’hayisa ach sameach. But other than the gematria, is there a source for this?

I think there very well might be.

WE are taught that the initial usage of a word or concept in the Torah reveals its essential definition. To determine the very essence of simchah, we need to identify its inaugural appearance in the Torah. Can anyone guess where that is?

It is in the most bizarre of places. In parshas Vayeitzei, Yaakov and his family escape from the house of Lavan, with Rochel appropriating her father’s avodah zarah. When Lavan discovers that his children, and his idols, have gone missing, he takes up the chase. He catches up to them and lets loose a torrent of furious castigations, reproving Yaakov in particular for departing his home without informing him first.

“Why did you flee in secrecy?” he demands, “Va’ashalechacha b’simchah uv’shirim, b’sof uv’chinor — I would have sent you off with happiness, and with music, with tambourine and with harp!”

That, believe it or not, is the first time the word “simchah” appears in the Torah. “I would have sent you off with happiness, and with music…”

Huh? Lavan? In this furious rant lies the very defining theme of simchah?

How on earth could that be?

To gain insight, we have to better appreciate what Lavan was saying. At first blush, the whole “I would have escorted you with happiness” thing sounds laughable. Oh, really? The oh-so-noble Lavan would have escorted Yaakov with such pomp and ceremony?

Perhaps we’re missing something here. Lavan was a rotten character, no doubt about that. But there happens to be one praiseworthy virtue that the Torah reveals about him. In parshas Chayei Sarah, when Eliezer arrives in Charan, Lavan says to him, “Lamah saamod bachutz — Why are you standing outside? V’anochi panisi habayis umakom lagmalim — and I have cleaned out the home and [made] place for the camels.” Rashi tells us that the “cleaning of the house” refers to avodah zarah. Lavan removed all avodah zarah from the home to accommodate Eliezer.

Now, we know how much Lavan cherished his avodah zarah. When his idols were snatched away from him upon Yaakov’s escape, he was utterly furious, turning the tents of Rochel, Leah, Bilhah, and Zilpah upside-down in search of them.

And yet, for the sake of making Eliezer comfortable, he removed these very idols from his home. He fulfilled the mitzvah of hachnassas orchim even though it was supremely difficult for him.

And in line with the segulah revealed by Rav Pinchas of Koritz, he must have been blessed with supreme simchah in return.

I have circumstantial evidence that Lavan, in fact, was privy to great simchah. The Gemara in Sanhedrin (105a) teaches that Lavan and Bilaam were one and the same. This is obviously difficult to understand, as they appear centuries apart from each other. Many mefarshim weigh in on this; one way or another, their souls were intrinsically bound together. Lavan and Bilaam share a common spiritual essence.

Why is this relevant?

Because we know that Bilaam had access to an awesome level of prophecy. The pasuk in V’zos Habrachah says “V’lo kam navi b’Yisrael k’Moshe — and there will not arise a prophet in Israel like Moshe.” The Sifri comments that this is true within Israel — “aval b’umos kam! — among the nations of the world there will be a prophet like Moshe!” Who is that? Says the Midrash: Bilaam.

Bilaam had the highest level of prophecy. The Gemara in Shabbos (30b) tells us that for a navi to experience prophecy, he must be in a state of simchah. Presumably, this applies to Bilaam as well. For him to receive such lofty levels of prophecy, he must have been able to access the highest levels of simchah. Indeed, Tanna d’Bei Eliyahu says that when Hashem allowed Bilaam to curse the Jews, he was “samach simchah gedolah — rejoicing with great happiness.”

And so we see that Bilaam, spiritual counterpart of Lavan, and thus presumably Lavan himself, was a very happy person.

Strangely, it seems that Bilaam also took hachnassas orchim seriously. When Balak’s emissaries arrived at Bilaam’s home, he said, “Linu poh halailah — sleep here this night.”

Bilaam doesn’t seem like that kind of guy. Sleep here? You’d expect him to say something like, “Find a park bench and knock yourselves out.” But he didn’t. He offered them space in his own home — an expression of hachnassas orchim, from which he merited the joy that granted him singular prophecy.

When Lavan excoriated Yaakov for fleeing without notice, he insisted that, had he been informed, he would have sent him off with “happiness, music, tambourine and harp.” Maybe he wasn’t kidding. Rashi in Kesubos (8b) and Sotah (10a) tells us that hachnassas orchim is comprised of three parts: “achilah, shesiyah, levayah — providing food, drink, and escort.”

Lavan, who did nothing good other than hachnassas orchim, was righteously angry. “I could have escorted you,” he fumed, “I could have fulfilled the third and final element of hachnassas orchim, through which so much simchah could have been gained. How dare you deprive me of that!”

This is the first appearance of simchah in the Torah — and, perforce, the very essence of simchah. Because going out of your way, making yourself uncomfortable for the sake of inviting someone else inspires the blessing of simchah — even to the Lavans and Bilaams of the world.

Isru Chag Pesach this year marks the second yahrtzeit of a man whose entire existence was characterized by simchah. Reb Michoel Schnitzler z”l is largely seen as the pioneer of the “wedding singer” industry, bringing joy to so many thousands throughout his career. He was a ball of energy, always with a smile on his face and eliciting the same from all in his presence.

What was his secret? How did he merit to become such a joyous person? One can only guess, but consider this story (published in The Moment, Issue 1010).

As a popular wedding singer, Reb Michoel grew familiar with the many unfortunate individuals who attend weddings in an effort to collect desperately needed funds on behalf of their families. When it came time for Reb Michoel himself to celebrate the wedding of a son, he approached each of these solicitors and extended personal and sincere invitations to his son’s upcoming wedding. The night of the wedding arrived, and Reb Michoel was about to walk his son down the chuppah, when, suddenly, a well-dressed man approached.

“Mr. Schnitzler?”

“Uh, yes?” Reb Michoel responded, somewhat disconcertedly.

“Mr. Schnitzler, do you recognize me?”

Reb Michoel shook his head.

“I would like you to meet my wife.” The man beckoned to a woman who approached, also elegantly dressed.

“Mr. Schnitzler,” the man explained, “I’m one of those beggars you invited. My wife and I have lived in Brooklyn for 28 years. This is the first wedding we’ve been invited to.”

Reb Michoel extended invitations to those who had never been invited — can there be greater hachnassas orchim than that?

It makes perfect sense that Hashem should reward him with an abundance of natural simchas hachayim.

This year, when you see a fellow in shul who looks like he could use a friendly invitation, think about Reb Michoel. And jarring a conflict as it is, think about Lavan as well. They did it, you can too.

In the merit of hachnassas orchim, may we see the true joy inherent in the Shalosh Regalim.

Wait.

Shalosh Regalim.

Is gematria.

(Originally featured in Mishpacha, Issue 1056)

Oops! We could not locate your form.